PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

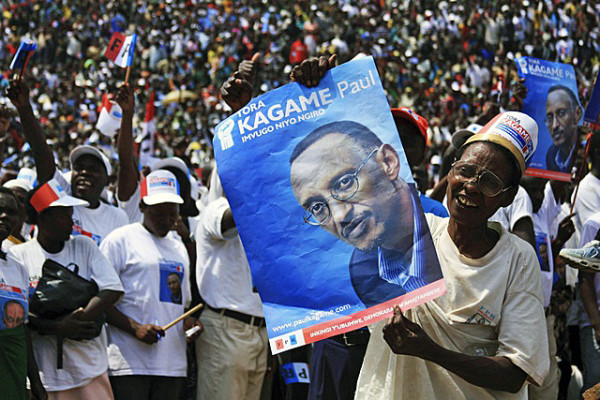

AUTHORITARIAN RESILIENCE IN RWANDA AND ETHIOPIA

Hilary Matfess:

The development community’s analysis of fragile states overlooks the variety of governance patterns exhibited by these countries. Most notably, it frequently does not take into account the differences between authoritarian states—some may be highly exclusive economically, others may be focused on shared growth; some may depend on weak institutions, others on relatively strong governing bodies; and some may have little legitimacy, while others have significant levels of it. This oversight prevents the formation of effective policy in the short-term and is counter-productive to efforts to advance democracy in the long run. As an example of the shortcomings of the current approach, I want to examine how governance in Ethiopia and Rwanda challenges the current understanding of fragility and illustrate a new sort of authoritarian rule.

These regimes derive their legitimacy from a number of sources—in particular, the Rwandan and Ethiopians governments’ paths to power (both of which led to the end of brutal regimes), and their longstanding commitment to economic growth and raising the standard of living within their respective borders have generated significant degrees of legitimacy despite their unwillingness to test their positions in free and fair elections.

Under the leadership of the militias cum ruling parties, the Rwandan Patriotic Front and the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, Rwanda and Ethiopia have come to be examples  of African success stories, outperforming other countries in the region. They have strengthened the effectiveness of the state, improved public services, reduced poverty levels, and produced sustained improvement in per capita incomes in ways that their neighbors have not. While they remain impoverished, both countries have experienced rapid economic growth—since 1990, GDP per capita in Ethiopia has risen from $252 to $454, while GDP in Rwanda has risen from $353 to $620.

of African success stories, outperforming other countries in the region. They have strengthened the effectiveness of the state, improved public services, reduced poverty levels, and produced sustained improvement in per capita incomes in ways that their neighbors have not. While they remain impoverished, both countries have experienced rapid economic growth—since 1990, GDP per capita in Ethiopia has risen from $252 to $454, while GDP in Rwanda has risen from $353 to $620.

These states have also demonstrated a willingness and capacity to promote improvements in citizen livelihood beyond economic growth. Both have significantly decreased the proportion of their population living below $1.25 a day—between 2005 and 2011, Rwanda’s poverty headcount has fallen 12 percentage points, whereas Ethiopian poverty levels fell by half from 1995 to 2011. Rwanda’s successful public health campaigns, especially with regards to HIV/AIDs, have earned the country praise and partnerships with international programs such as PEPFAR and UNAIDs. Similarly, Ethiopia’s continued agricultural growth and reform efforts have garnered it international investment and funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and others. The developmental orientation of these regimes has earned them legitimacy domestically and gained them support among donors.

Through politically controlled investment firms, they have guided investment into industries that advanced development. In Rwanda, Tri-Star Investments/CVL is owned by the Rwandan Patriotic Front, but is not an official government body. This firm was a principle investor in “metals, trading, road construction, housing estates, building materials, fruit processes, mobile technology, printing, as well as furniture imports and security services,” sectors that have contributed significantly to Rwandan growth in the past two decades. Similarly, EFFORT in Ethiopia is a significant investor in critical sectors such as “transport logistics, engineering, construction, and import-export,” and is managed by the politically-connected Tigray ethnic group.

On the other hand, the two authoritarian regimes have used political repression to stay in power, often framing it as a means of protecting citizens from sliding back into the sort of chaos and poverty that characterized the countries before they came to power. Both states are de facto one party states that exert considerable control over the political discourse within their borders. The 2014 Freedom House report classified both states as ‘Not Free’ and noted a deterioration in the freedom of the press in Rwanda and Ethiopia, falling 17 points and 9 points on a scale of 100 since 1994, respectively.

On the other hand, the two authoritarian regimes have used political repression to stay in power, often framing it as a means of protecting citizens from sliding back into the sort of chaos and poverty that characterized the countries before they came to power. Both states are de facto one party states that exert considerable control over the political discourse within their borders. The 2014 Freedom House report classified both states as ‘Not Free’ and noted a deterioration in the freedom of the press in Rwanda and Ethiopia, falling 17 points and 9 points on a scale of 100 since 1994, respectively.

Reporters Without Borders has raised concerns about the persecution of journalists in both countries. In addition to restrictions on the freedom of press, Rwanda has restricted freedom of speech and has demonstrated intolerance towards political opposition. Victoria Ingabire, a high-ranking member of the opposition FDU-Inkingi party, was arrested for violating anti-genocide laws after she made a speech calling for reconciliation between Hutus and Tutsis. When her party attempted to register for the 2010 election, they were physically abused as police officers observed.

Extrajudicial assassinations of the Rwandan Patriotic Front’s political opponents are not unheard of in Rwanda—in January 2014, political dissident Patrick Karegeya was murdered in South Africa. The Ethiopian Charities and Societies Proclamation in 2009 stipulates that any organization that receives more than 10% of its funding from outside of the country’s borders is considered ‘foreign.’ These organizations are banned from working on issues connected to human rights, women’s rights, children’s rights, disability rights, citizenship rights, conflict resolution, or democratic governance. The law has placed civil society in a stranglehold.

Both governments have also successfully leveraged the threats stemming from their unstable neighbors (the Democratic Republic of the Congo for Rwanda and Somalia for Ethiopia) in order to stymie political opposition, using the threats to legitimate their rule, both domestically and internationally, while oppressing domestic dissent.

The repressive tendencies of these regimes has undermined to some extent the legitimacy they have built up; in response both also have attempted to use the institutional trappings of democracy to augment their legitimacy domestically and support internationally. By holding regular elections, these regimes garner some degree of political support domestically while being able to nominally abide by the demands of donors’ ‘governance agenda.’ In both cases, opposition parties are capable of winning a nominal amount of power without presenting a serious challenge to the dominant party’s rule. As Andreas Schedler predicted, these regimes “neither practice democracy nor resort regularly to naked repression,” but by adopting certain democratic institutions “obtain at least a semblance of democratic legitimacy, hoping to satisfy external as well as internal actors.”

The political mobilization and repression in election years have, however, revealed cracks in the regimes’ control. In 2005, when the opposition in Ethiopia made record gains in representation, the Ethiopian state responded with a brutal crack-down on free speech, the press, and political opposition—though the EPRDF remained in power and elections continued to be regularly held. Similarly, in Rwanda, opposition groups are allowed to register and campaign, however they are subjected to legal and physical abuse—when the FDU-Inkingi party attempted to register for the 2010 election, they were physically abused as police officers observed.

Given the strength and legitimacy of these developmental electoral authoritarian states, a transition to democracy should not be considered inevitable, at least in the short-term. The governments’ ability to promote economic growth, reduce poverty, provide critical public goods, and adopt certain democratic institutions, while suppressing political challengers resembles the pattern followed by a number of East Asian countries—including South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Indonesia—but which has limited history in Africa. As such, it constitutes a novel form of governance that requires further study. The state’s co-opting of the bourgeois class, and funneling of investment though the ruling party slows down the development of the sort of democratizing middle class that emerged in other industrializing societies.

These countries’ successful track record and the entry of non-Western actors such as China into the African arena has also reduced international pressure to democratize. The United States’ military relationship with Rwanda and Ethiopia, predicated upon their proximity to failed states and their willingness to cooperate with and assist American forces, partially insulates these regimes against strong criticism. Additionally, given that both states hold regular elections, one of democracies most defining characteristics, demands for democratic reform is more difficult.

The governance patterns of Rwanda and Ethiopia provide a challenge to those who argue for the inherent fragility of authoritarian regimes, especially in the short-term. Developing effective policies to assist fragile states requires a more nuanced understanding of the heterogeneity of governance in these states.

Hilary Matfess is a graduate student at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, pursuing a degree in International Economics and African Studies. Her primary focuses are modern African political economies and governance issues. Follow her on Twitter @HilaryMatfess.

Hilary Matfess is a graduate student at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, pursuing a degree in International Economics and African Studies. Her primary focuses are modern African political economies and governance issues. Follow her on Twitter @HilaryMatfess.