PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Airstrikes ‘won’t deter migrants’

In the small Libyan port of Zuwara, one of the main points of departure for migrants seeking to reach Italy, dozens if not hundreds of fishing boats line the quay. It’s an innocuous sight: blue wooden skiffs knocking against each other in the breeze. But if Europe wants to use military force to smash Libya’s smuggling trade, these are the boats they will have to destroy.

This week, the European Union will seek to persuade the United Nations Security Council to back military operations against smuggling fleets in Zuwara and other coastal towns up and down Libya’s western seaboard. But even with the UN’s go-ahead, such a strategy may not be straightforward – and the blue boats bobbing in the harbour in Zuwara illustrate why.

Contrary to mainstream portrayals, Libya’s smugglers are not one cohesive organisation with a clear chain of command or identifiable assets. They do not have an easily targeted fleet at their disposal, anchored in areas separate from civilian life.

Instead, they usually source their boats on a trip-by-trip basis from local fishermen. At current prices, they pay more than 140 000 dinars (£70 000) for a fishing boat that might carry 300 migrants. Even after money has changed hands, the transition will be imperceptible to all but the few aware of the transaction. Today’s smuggling vessel was yesterday’s fishing trawler.

Minor players and kingpins

Watching the port’s comings and goings by satellite, a European spy would have little concrete indication that any particular fishing boat was leaving the harbour for untoward reasons.

However, the smugglers’ boats leave port in the early evening, an odd time for a fisherman to be going to work. In another telltale sign, they tend to drop anchor in deeper waters a few miles out to sea as they wait for the migrants to arrive in inflatable dinghies. But no one could be sure of wrongdoing until those boats started to be loaded with hundreds of passengers – too late for airstrikes from any ethical navy.

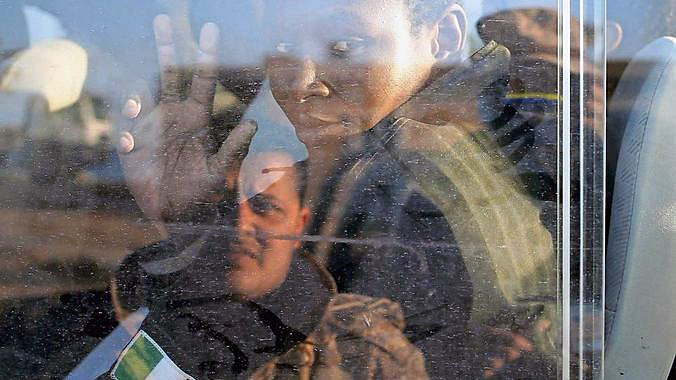

Arresting or killing the smugglers would also be a struggle. Those sailing the boats are minor players: either migrants trained for the task or fishermen enlisted for one-off trips.

The kingpins stay on terra firma and any attempts to rein them in would do little to dent the sprawling, often separate smuggling operations to the south that ferry thousands of migrants through dozens of way stations spread across the northern half of Africa.

In any case, the Libyan coast is no longer just the preserve of a few experienced criminals. Instead, smuggling is increasingly a start-up business, powered by a growing number of overlapping and informal networks that emerge, morph and fade by the week.

As one Zuwaran says: “No one has the word ‘smuggler’ written on their chest. Anyone here who has no money can sell their apartment, buy a boat and organise a smuggling trip. By the time of the next trip you’d already have regained half the cost of the apartment. It’s a very easy formula.”

Obstacles

Behind the scenes, European politicians and policymakers are aware that, whatever happens at the UN, military action will take time to plan and finesse. It may be months before it is operational, by which time the smuggling season may be over.

But even with a more nuanced and cautious approach, there are other obstacles. The first are Libyans themselves, who are ruled by two rival governments. The capital, Tripoli, and most of the smuggling towns in the west are controlled by rebels collectively known as Libya Dawn. The elected government has retreated to cities in the far east.

At odds over most other issues, both governments reject foreign intervention. Libya Dawn says smuggling can only be curbed once it is internationally recognised, a spokesperson said. The eastern government argues the opposite: that smuggling will end once the international community gives its soldiers the weapons to finish off the western rebels.

Whoever wins, a stable Libya and a reunited police and coastguard will inevitably make it harder for smugglers to operate. But even if Libya is reunited, it will still be difficult to end a trade that is the result not only of a huge security vacuum, but also very few economic alternatives in smuggling communities.

One Zuwaran smuggler said: “I went to college, I graduated with a law degree, but I had no job. And when you don’t have a job and someone says: ‘Can you get a boat for me?’ and it comes with a $22 000 profit, it’s a good opportunity.”

Perhaps the biggest obstacle is the migrants themselves. Amid the largest wave of mass migration since World War II, the refugees will keep coming or go by other routes.

As one Syrian said: “Even if there was a government decision to drown the migrant boats, there will still be people going by boat, because the individual considers himself dead already. I don’t think that even if they decided to bomb migrant boats it would change people’s decision to go.”