PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

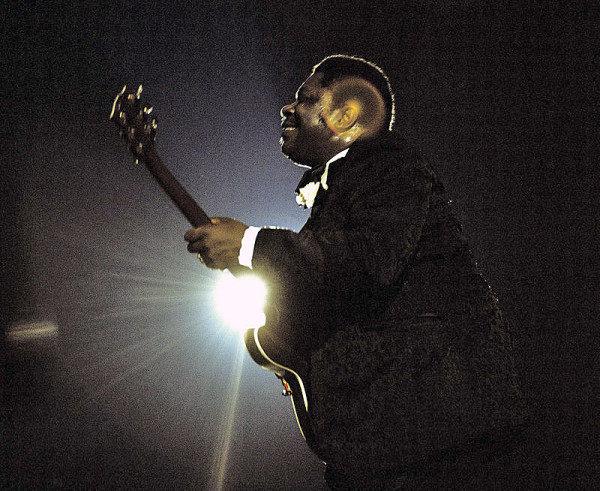

B.B. King And The Majesty Of The Blues

MARK ANTHONY NEAL, 16

More than 25 years ago, Stanley Crouch wrote the sermon “Premature Autopsies,” which was dutifully delivered by Trinity United’s Rev. Jeremiah Wright (likely around the same time he met a young Barack Obama) on Wynton Marsalis’s 1989 recording Majesty of the Blues. The centerpiece of Crouch’s sermon, which challenged perceptions that Jazz was dead, was the singular example of Duke Ellington, who as Crouch asserts, “never, never came off the road.” Ellington’s genius was as much his ability recognize great musicians who could interpret his vision of the music as it was his understanding that the music would only survive if he and others were willing to take it to the people. Like so many of the musicians of Ellington’s generation who understood both the blessing and the curse of the Chitlin’ circuit, where black artists survived shoddy treatment for the chance to have a connection with the people for whom the music was so crucial, Ellington also understood, particularly after his groundbreaking performance at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1956, that staying on the road was also about delivering the message of “The Majesty of the Blues,” which to say the majesty of America’s national music.

When Ellington died in May of 1974, he may have bequeathed the responsibility of keeping the music alive to a guitarist from Mississippi who initially made his name in Memphis in the late 1940s as “Blues Boy” King. Indeed B.B. King appears on a 1970 Ellington album called Stereophonic Duke Ellington, where he contributes vocals to the Ellington classic “Don’t Get Around Much Any More,”

At the time of Ellington’s death, King was the undisputed “King of the Blues”— the most recognizable and accessible icon of a sound that was in flux. As a generation of white British blokes sang the praises of Mr. Waters (who played Newport a few years after Ellington), Mr. Dixon, Mr. Hooker, Mr. Wolf, and Blues artists found both an audience and increased pay days in Europe and touring on the rock circuit, artists like Albert King (“Born Under a Bad Sign“) , Little Milton (“We’re Gonna Make It“) and B.B. King found themselves trying to tread the muddy waters of crossover by gravitating to the audiences that Stax, Atlantic and even Motown had cultivated.

With the release “The Thrill is Gone” (1969), B.B. King solidified his role as Black music’s ambassador to the world. Throughout the 1970s King also found crossover success with singles like “Ain’t Nobody Home” (1972) and “To Know You Is To Love You” (1973), which was written and originally recorded by Stevie Wonder and Syretta Wright; Wonder appears on the King version, effectively capturing two generations of black music listeners, at a moment when Wonder was ascending to his own iconic status. By the time King released 1974’s Friends, with the title track and the instrumental “Philadelphia,” which sounds like the best of what was produced at Sigma Sound Studios in that era, the mainstream pop audiences were gone, looking more for nostalgia from the Claptons and Steve Millers of the world than forward thinking from “old” Blues musicians.

King’s early- and mid-1970s soul albums, like Friends and To Know You is To Love You, were important, because as young black audiences were running from the blues in droves, it was an attempt to draw them back in. (Miles Davis was attempting much the same with On the Corner in 1972.) When I was a child growing up in the Bronx in a Southern household, King, and Hammond B-3 specialists like the Jimmies — Smithand McGriff, and gospel groups like the Mighty Clouds of Joy and the Soul Stirrers were mainstays. I was gonna hear the blues cause it was my daddy’s soundtrack, but hearing King sing songs like “To Know You,” “Friends,” and “I Like to Live the Love” on WBLS, New York City’s black-owned radio station, made him relevant to ears that only wanted to listen to The Jackson 5, The Spinners and the Honey Cone. My most intense memories of King’s music in that era were his two live recordings with his old friend Bobby “Blue” Bland, Together for the First Time (1974) and Together Again(1976), especially tracks like their cover of Bland’s classic “That’s the Way Love Is” and the First Time closer “I Like to Live the Love”; Even Jay Z gives a h/t to the latter song on “Ain’t No Love” (“take em church”).

King understood, perhaps intuitively, that if it was now his job to claim the Majesty of the Blues, he couldn’t make such a claim without the co-sign of black youth, who even then, were arbiters of American cool. King spent much of the last 30 years of his career as the blues’s Shaka Zulu, bringing anyone and everybody under the umbrella, often with the kings of rock, like the aforementioned Clapton and even U2 singing his praises. King’s most successful recordings, 1997’s Deuces Wild — 17 tracks with 17 different artist ranging from Van Morrison to Heavy D, Bonnie Rait and D’Angelo — and his 2000 collaboration with Clapton, Riding with the King, which went double platinum and earned the duo a Grammy Award, were both examples of how successful King’s efforts were. And yet in between those successes, King releases Let The Good Times Roll, a tribute to the music of Louis Jordan, the patron saint of black music’s crossover appeal. If King was now the standard bearer of American music, Jordan was his openly acknowledged inspiration.

For those who’ve seen King’s concerts over the last decade or so, it’s less about the virtuosity that made him matter in his earliest days, and more about the presence of the figure himself. The audiences are some of the most diverse you could expect, though typically more White than anything. The last time I saw King, live at an outdoor jazz festival, he called the children in the audience up to the stage, and handed each one of them one of his signature guitar picks. It was an important gesture towards making sure that even the youngest of folk understand that the Majesty of the Blues wasn’t about being above the people, but being among them. Ellington would be proud.

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of five books including What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture (Routledge, 1999) and Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities (NYU Press, 2013). He is Professor of African & African American Studies at Duke University, where he directs the Center for Arts, Digital Culture and Entrepreneurship. Follow him on Twitter at @NewBlackMan