PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

How Bismarck plundered Africa’s juiciest riches

By Adekeye Adebajo 18 MAY 2015, Business Daily (South Africa)

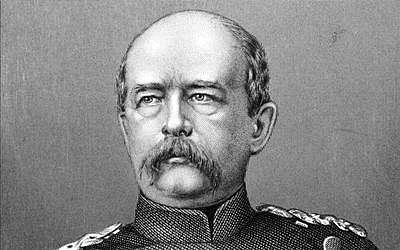

LAST month, Germans celebrated the 200th anniversary of Otto von Bismarck’s birth. The Prussian statesman united Germany, but divided Africa.

Bismarck became chancellor of Germany in 1871, the same year he united the plethora of princely Germanic kingdoms through means of “iron and blood” following three wars with Denmark, Austria and France. The German political sorcerer then played the role of “grand wizard” at the Berlin conference in 1884-85, employing the technology of the industrial revolution to divide Africa.

The “Iron Chancellor” was a vain and arrogant man with boundless energy and a huge appetite for food and drink. He became known as the “honest broker” who established an intricate network of political alliances that largely preserved peace in Europe for four decades.

He was a colossus who bestrode the German Reich (empire) unchallenged for two decades, and a political genius of realpolitik. Under him, Germany became the leading industrial and military power in continental Europe.

Bismarck had previously opposed colonies in Africa, finding them a drain on resources. Pushed by German economic interests, he changed his mind chiefly because he regarded Africa as an extension of the struggle for leadership in Europe.

The “new imperialism” that erupted into the “scramble for Africa” by the 1880s was often described in terms of a game that appeared to be played by petulant and pampered public schoolboys in the English tradition. Bismarck often talked derisively of the Kolonialtummel (the colonial whirl).

By the time the gun was fired before the dawn of the “naughty nineties”, plundering fin de siècle European imperialists were pursuing the “race to Fashoda”, “blind man’s bluff”, the colonial “steeplechase”, and the “gambler’s kick”, seeking their own place in the African sun.

This epic drama involved squabbling colonial governments; devious explorers such as David Livingstone and Henry Stanley; vicious capitalist-politicians such as Cecil Rhodes and King Leopold; and sanctimonious Christian missionaries. Africa was often described as a giant fruitcake to be devoured in juicy morsels at the imperial banquet in Berlin: Tunis was a “ripe pear”, while terms like “plums” and “cherries” were bandied about.

The conference at which the rules were set to partition Africa took place in Bismarck’s residence in Wilhelmstrasse in Berlin in 1884-85. Fourteen largely western powers (Germany, France, the UK, Portugal, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Russia, Austria-Hungary, the US, Denmark, Sweden/Norway, the Netherlands and Turkey) attended. Significantly, no African representatives were present, even as princes, barons, counts, lords and other delegates discussed the continent’s future.

Bismarck started the conference with a speech in French that championed David Livingstone’s “three Cs”: commerce, Christianity and civilisation. The more malign “three Ps” may have been more accurate: profit, plunder and prestige. He disingenuously argued that the conference aimed to promote the “civilisation” of the “natives” by opening up Africa’s interior. The chancellor ended by hoping the meeting would serve the cause of peace and humanity.

Anglo-French rivalries lay at the heart of this conference, with Bismarck throwing his weight behind Paris then London to ensure that they continued to remain rivals. One of the most significant outcomes of Berlin was Bismarck’s successful support of Belgian King Leopold’s annexation of the Congo, triggering the start of widespread atrocities and forced labour on rubber plantations that resulted in about 10-million deaths.

In his final speech to the conference, Bismarck summarised its achievements: free access for all western nations to Africa’s interior, free trade in the Congo basin and consideration for the welfare of the “native races” in providing them with the benefits of “civilisation”. Berlin had set the rules for trade, navigation and control of Africa to avoid conflicts among European nations. In the next 25 years, almost the entire land mass of Africa was parcelled out among European powers.

Berlin represented a banquet at which European imperialists feasted on territories that did not belong to them. They sought to cloak their fraudulent scheme with patronising and paternalistic moral platitudes of a “mission civilisatrice”.

It would be hard to find better examples of a single meeting that had such devastating political, socioeconomic and cultural consequences for an entire continent.

• Adebajo is executive director of the Centre for Conflict Resolution and Visiting Professor at the University of Johannesburg.