PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

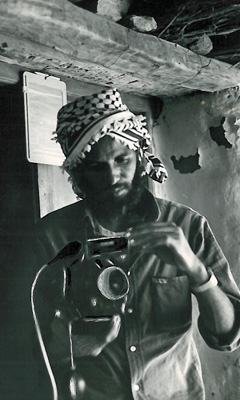

Tales of an Eritrean fighter-photographer

Greg Marinovich, 2 Dec. 2015, Aljazeera (English)

Vanessa Berhe’s mother tried hard to teach her daughter about the rich culture and history of her ancestral home.

Born in Sweden to Eritrean parents, Vanessa would listen to her mother’s stories about a land where towering mountains dropped precipitously towards the sweltering and inhospitable Red Sea coast. Woven into these stories were the epic tales of the Eritreans who had, for 30 years, fought against Ethiopian rule, finally attaining statehood in 1993.

Her uncle, Seyoum Tsehaye, was one of them.

Dreams lost and found

As a child, Seyoum dreamed of becoming a journalist. But as he learned of the atrocities committed by the Ethiopian government against Eritrea, he knew he would have to put his ambitions aside. Eritrea had been declared an autonomous part of the Ethiopian Federation in 1952. But, 10 years later, Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie had dissolved the federation and annexed Eritrea.

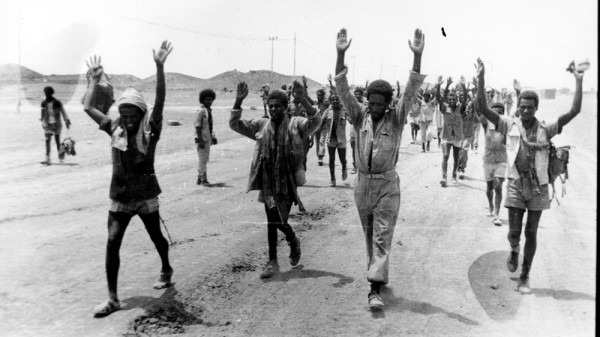

In 1977, as a 25-year-old university student, Seyoum joined the fighters of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front. The EPLF had split from the Eritrean Liberation Front during the 1970s. At points in the conflict, the two groups would turn their guns on each other, but both well understood the importance of documenting their struggle. They each trained some of their fighters to use still and film cameras and, after four years fighting on the front lines, Seyoum received orders to report for training as a cameraman.

In photographing and filming the conflict, Seyoum found his calling. And the liberation movement found one of its most effective witnesses. But it wasn’t an easy role. When I met Seyoum several years later, he described his work to me. It was 2001 when I went to Eritrea to conduct research into the corps of Eritrean liberation fighter-photographers and Seyoum was, by then, a middle-aged man with balding pate and a lush moustache. Unlike many of his peers, who preferred not to discuss the work they did, Seyoum spoke passionately about it. Some of the memories he shared still moved him to tears or laughter.

“You feel guilty when you take all these pictures. It is different for somebody who is helping these people, than [it is] for somebody who is taking pictures, just standing over someone who is dying or bleeding,” he said. “You suffer the video, and you know the rule: you cannot cut it in a fraction. You have to stay longer and the more you stay with the agony, with the crime, with the suffering, the more you suffer.”

But his duty as a soldier was to follow orders and his orders were to record an endless series of war crimes committed against his people. Inside, he said, he died a little every time he had to film his compatriots bleeding.

“For about a month, I couldn’t sleep, all these people come in the night in front of me like a video, you know, all of them.”

Hard habits to break

Then, in 1991, the war came to an end. The EPLF had defeated the Ethiopian forces in Eritrea. In Ethiopia, meanwhile, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, which had been engaged in a civil war against the Ethiopian government, came to power. Two years later, the Eritrean people voted overwhelmingly in favour of independence in a referendum held with the support of Ethiopia’s new ruling party.

The EPLF, which had been renamed the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice, was now in power.

But the habits of war were hard to break, and the newly elected government ruled the country much as they had run their liberation movement. Demobbed fighters were assigned new forms of national service, whether planting trees to combat soil erosion or rehabilitating the country’s colonial era steam railway system, the steel rails and heavy wood ties of which had been dug up and used as bomb shelters during the war.

Seyoum was appointed director of Eri-TV, the state broadcaster. He later became the head of tourism.

A split in the ruling party ensued, with the emergence of a faction led by the head of the army and some cabinet ministers. This desire for reform also found a more grassroots expression through the blossoming of independent newspapers and through individual employees at the state broadcasters. Seyoum was part of this movement. He began working in independent film production and became a regular contributor to the independent newspaper Setit. The paper was a thorn in the government’s side.

Some veterans of the struggle, as well as some younger Eritreans, felt that they had a right to more than just national sovereignty – they wanted personal and political freedom too. For a while, the state tolerated this free press and dissent among the elite, but then, in 1998 a new conflict broke out between Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Triggered by a dispute over the border town of Badme – which both sides claimed and which, in 2002, a boundary commission ruled should fall inside Eritrea – the war lasted for two-and-a-half years.

Each side endured huge losses, and while exact numbers are disputed, the number of casualties was estimated at between 70,000 and 120,000. Seyoum felt it was his duty to cover this new war, as he had the last. But, this time around, reporting was heavily censored.

Since film cameras and editing equipment were expensive, he requested that the Ministry of Information equip him to film the war. In turn, he promised to provide all of his footage to the state. He didn’t want to be paid and simply saw it as a continuation of the work he had done during the struggle for liberation. The state refused. Neither would it allow him to travel to the front line. The veteran journalist was barred from documenting the war.

Seyoum soon began to question the war’s rationale, writing regularly for the country’s largest independent newspaper. Why did the blood of yet more sons and daughters have to nourish the country’s already-sated soil, he wondered?

Paying the price

When I met Seyoum in early 2001, the border war hadn’t long ended and the cracks within Eritrea’s leadership were becoming more apparent. Haile Woldensae, the minister for trade and industry and a cofounder of the ruling party, agreed to speak to me about it. He questioned the failure of the government to make the transition to true democracy, acknowledging his role in this as one of the leaders of the liberation fighters who had been at the forefront of the movement’s totalitarian tendencies. For many decades, he had even been in charge of its propaganda.

“We have to suffer from what we have done before. In following one line of thought, one school of thought, there are costs that one has to pay,” he said, referring to the propaganda campaign the liberation movement had run throughout the war. The effects of this totalitarian approach seemed evident in the way many Eritreans refrained from openly expressing dissatisfaction with their government.

But it had served a valuable purpose at the time, the minister explained. “That ideology was a very motivating thing and the people were very committed. That is why, in the liberation struggle period, the photographers – the propagandists – had an important role in the society,” he said.

“But it is not without a cost and it is particularly after independence that you start realising the cost: to not be very open, to not be very critical.”

Whispers and worries

All of the 2001 interviews I conducted were done in the presence of Paulos Zaid, an Eritrean journalist working for the state’s English language magazine, Eritrea Profile.

He had seemingly been assigned to work as a translator and fixer. But, in truth, his role was to report to the government on what the other Eritreans – Seyoum, Haile Woldensae and the others we spoke to had to say. Any signs of disloyalty to the regime were to be noted, he later told us.

But Zaid was no government stooge. Too young to have fought in the war of liberation, he was from a generation of Eritreans who sought a more democratic society. He was also under investigation on suspicion that he might hold liberal views about freedom of expression, and friends within the government had warned him that he was in danger of being forcibly conscripted or jailed.

We left Eritrea after a month. But when we tried to get in touch with Seyoum and Zaid a couple of weeks later by fax and email, we were unable to reach them. With the country’s first multi-party elections planned for December 2001, there was an intensified crackdown on dissenters. There were whispers about opponents of Afwerki being arrested, but the facts were hard to come by.

What we learned much later on was that on September 21, 2001, Seyoum was arrested at his home in Asmara, the Eritrean capital. He wasn’t alone.

At least 17 independent journalists were arrested in 2001. Some student leaders were also picked up, as were 11 cabinet ministers and ruling central committee members, who had been part of what became known as the G-15, a group of 15 people who had issued an open letter in May 2001, criticising the government’s failure to implement the constitution and its postponement of elections. Among those was Woldensae.

After months of silence, during which we had tried to contact Zaid, we eventually got word from him – an email sent from a refugee camp in Ethiopia.

He wrote: “It is now my 6th month since I left Eritrea on foot with only my sandals, single trousers and a shirt ….

“I left your address in my wallet, which I deliberately discarded at the jungle while I was crossing the mine-infested border with Ethiopia. At the moment, I do not have good news to tell you. If you remember my discussion with both of you at your hotel’s parking lot the night before you left, I was losing hope about and confidence in the much-talked politics of Eritrea. However, I did not realise that things would be falling apart at such speed as they have been doing in the past six months. Worse, the fire that is consuming many innocent Eritreans was to come to me if I did not flee on time ….

“A couple of weeks after you left, I was picked up by three agents on my way home who just told me that I was frequently seen with ferenjis [white people]. Seyoum Tsehaye was also detained after I left. I really do not know on what charges he was detained.”

The email went on to explain that Zaid was reaching out to the Committee to Protect Journalists and urging us to do the same on his behalf. He was hoping to get a visa for South Africa. But he couldn’t write much more, he explained, for “internet service is very expensive here – 0.75 cents a minute. I have so far sacrificed 10 cigarettes to write to you”.

A friend of Zaid’s, Kidane Yibrah, a sports journalist seconded into military service, had helped him flee. Yibrah, it emerged, had been leading a secret second life – as the founder of an underground newspaper that opposed the government.

With the help of the Committee to Protect Journalists, both Zaid and Yibrah were eventually able to get to the United States, where they were granted asylum. But Seyoum remained in jail.

Telling Seyoum’s stories

In Sweden, Seyoum’s five-year-old niece was told the news. Her uncle, who had featured so prominently in her mother’s stories, but whom she had never met, had been imprisoned. At school, Vanessa talked to her teacher and classmates of his plight. She struggled to understand how such a bad fate could befall such a good person.

By the time her uncle had been detained for a year, Vanessa and her classmates had started collecting money. They would buy a plane ticket and fly to Eritrea to free him, they decided. For Seyoum’s family in Sweden, the distance and lack of reliable information has made their plight all the harder.

The state has refused to answer their questions, and the only information they have obtained has come from former prison guards who have fled the country. One guard told them that, in 2002, Seyoum had gone on an extended hunger strike to protest against his imprisonment. Another guard confirmed this fact to Eritrean exiles in the US. But it is unclear just how long the strike lasted.

For many years, he was held in solitary confinement, the guards reported. But still he continued to defy his jailers by refusing to give his support to the country’s rulers. Vanessa is now 19 and explains: “We don’t know much about his imprisonment. After his hunger strike he was moved to another prison, the one he is in now, in 2015. The only thing we know is from a prison guard who fled in 2008 – he said only four of those originally arrested were still alive, including my uncle.”

The Committee to Protect Journalists has reported that seven journalists have died in detention in Eritrea, while Amnesty International said in a 2014-2015 report that they believed nine of the original journalists and politicians arrested in 2001 have died. Precise information is impossible to come by. “He [the guard] said Seyoum is still in a room by himself and with his ankles and wrists tied together,” says Vanessa. “This was because he was still in good physical condition even after all the years of jail.”

“Another guard said that my uncle said, ‘You can beat me, you can torture me but I will not give up what I believe in.'” The fate of Haile Woldensae is unknown; some believe he is still in detention while others claim he was executed, probably quite soon after his arrest. Human Rights Watch believes he was still alive in 2011.

As a high school pupil, Vanessa started to get more actively involved in raising awareness about the plight of her uncle and others in Eritrea.

“Most people don’t even know the country exists, and I wanted to tell about the human rights abuses there,” she explains.

“Currently, I am trying to inform people about Eritrea, like with the latest Eritrean exodus of refugees. Many countries want to give the Eritrean government money because they say that the refugees are economic refugees and if we give them money they will stay in their own country. They do not understand that they are political refugees,” she explains.

Her hope is to help not just Seyoum, but all of the country’s political prisoners. Together with various organisations and human rights lawyers, she has filed a habeas corpus demand for the Eritrean government to produce these detainees in a court of law, as is required by international law, as well as by Eritrea’s own constitution and laws.

“The story is so much bigger than Seyoum, bigger than a couple of individuals,” Vanessa reflects. “Today, all critical voices are silenced. Terrible stories about human rights atrocities are not heard. We want to tell the stories that Seyoum would have told, were he free.”