PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Ugandan woman forced to marry feared warlord explains why she would welcome him back

Jacqui Thornton | 15 December 2015 | The Independent

Prisca Lanyero makes a living selling charcoal and washing clothes. She lives in a rented mud and straw hut, with her children, aged eight and five. Their father, a feared commander in the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) that wrought terror in Uganda, is on trial at the International Criminal Court in The Hague on war crimes charges.

Speaking for the first time to The Independent about her life as the “forced” wife of Dominic Ongwen, the alleged leader of the LRA’s Sinia Brigade, Ms Lanyero, 22, said that when she was 10 she was abducted from home by the LRA and forced to live in the Congolese bush.

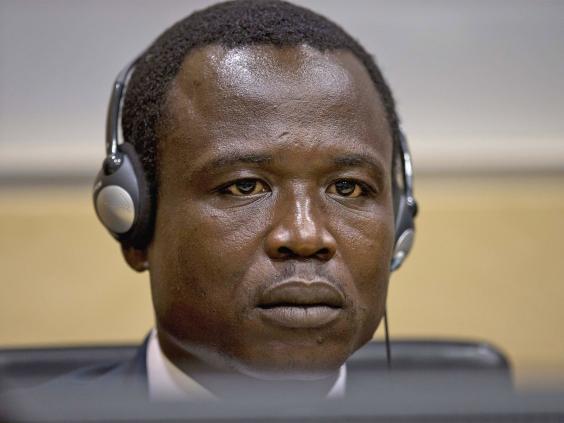

At 12 years old, she was given as a wife to Ongwen, who was himself abducted as a boy on his way to school in 1990. Ongwen – the most senior Ugandan rebel leader being prosecuted at the court next month – faces three counts of crimes against humanity, including murder and enslavement, and four counts of war crimes, including cruel treatment of civilians and pillaging.

Ongwen, a child soldier who rose through the ranks of Joseph Kony’s feared LRA, had a $5m (£3.3m) bounty put on his head by the US. Last January, he was handed to US special forces on the South Sudan border by the Central African Republic’s rebel Seleka movement.

Appearing before the ICC soon after his capture, Ongwen spoke only to confirm his identity and that he understood the charges. It is believed that more than 100,000 people have been killed, 60,000 children kidnapped and 1,200 babies born in captivity during the LRA’s 30-year campaign of terror in Uganda.

In the Gulu district, 250 miles from the capital, Kampala, Ms Lanyero, who had two children with Ongwen, the first at 13, said she believed her husband should be allowed to return home because he was a young victim himself and had no control over his life. Although the government introduced an Amnesty Act for former rebels in 2000, it did not apply to Kony and his four top commanders, including Ongwen.

But Ms Lanyero, one of a number of wives, said he was reluctant to fight when she was last with him. She believes he surrendered rather than be captured, which, she said, showed his lack of appetite for war. She knows little about the ICC but believes that Ongwen will return to Uganda – and when he does she wants him to come back to her and their children. She said: “All the atrocities maybe he has done, it was not his will. They gave him the order to do it, but if you don’t do it you were going to be killed and punished.”

Ms Lanyero believes Uganda’s amnesty will encourage the few remaining LRA soldiers to give themselves up. A peace process began in 2006 but collapsed, pushing the remaining LRA soldiers to operate in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the CAR and South Sudan. It is thought to have as few as 250 fighters left. She added: “It will give hope to people still in captivity. There are so many people who are scared of Dominic’s case. If they jail Dominic or keep him at the ICC, people will not come back.”

Initially, Ms Lanyero wanted to escape from captivity, but she was severely caned as a warning. She did not want to be Ongwen’s wife. “I had no voice. I was too young,” she said. However, she came to love her captor after he rescued her from an ambush by Ugandan government forces, in which she was shot in the thigh and arm. She misses Ongwen because of the kindness he showed her. “I would have been killed without him,” she said. “I was shot almost to death. He was the one who carried me and nursed me until I recovered. That’s why I cannot forget about him. After seeing all the help he has shown me, I even started loving him. He used to love me but [now] I don’t know.”

She was released in 2011 by another commander when Ongwen was on a mission, and she now lives in Gulu district. Weeping quietly, Ms Lanyero said she had no family support because her mother died this year and her father, a Ugandan army soldier, was killed fighting in the month she was released. “It is still better than captivity,” she added.

Despite her hardships, she is still strikingly beautiful. Wearing a blue scarf around her head, a black top and a pink skirt, her colourful clothes contrast with the grey floor of her rented mud hut, whose only light is the tiny doorway. Ms Lanyero said Ongwen was generally “friendly to everyone”. He was, she recalled, “kind sometimes, but when one of the wives did something wrong, he would normally punish all of them with the cane”.

She believes Ongwen should be allowed to return home to be a proper, supportive father. She said: “He should come back to his family and, in case he is interested in me, I will come to him and keep our children together.”

However, she said that Kony, who has evaded capture and is believed to be in the Kafia Kinji region on Southern Sudan’s border, should be tried. “All of what has happened in the LRA came out of him. He is the commander, he is the one ordering people to do things, he is the one abducting people and he is the one giving girls to men.”

One such victim is Mary Aol, 50, who had her lips cut off when she was 22 for failing to give rebels money during a raid. A commander forced a child soldier aged about 11 to disfigure her, warning that he would “go to work” on him if he did not follow orders. Ms Aol said: “The boy was afraid. I kept staring at him. There was mercy in him, but the order was so strong by the commander, who said, ‘Do it right now. I want to see her jaws’.”

The stigma felt by the LRA’s victims is being tackled by an agricultural programme backed by the charity World Vision. It encourages them to work as farmers and mix with other community members while providing a family food supply. One participant is Okot Bitek, 54, who was abducted at 35 with his 15-year-old son. The boy begged the LRA to let his father go and take him instead. Mr Bitek said: “They said: ‘OK, we are going to send your father back home.’ They shot me in the neck immediately. I fell down and they started moving. That was the last time I saw my son.”

Her opinion is echoed by many in Gulu, where the tell-tale signs of slashed lips, noses and ears, and violent canings, are commonplace. If any feel Ongwen should be held to account, they do not voice it; they reserve their ire for Kony.

More than 15,000 former abductees have returned to their homes after escaping or being released in the Gulu area. They have experienced rejection and stigmatisation, not only from their villages but also their families. As captives, they were forced to torture their former neighbours during raids for food, money and new LRA recruits.