PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

The Global Conflicts to Watch in 2016

Uri Friedman | 17 Dec 2015 | The Atlantic

Concerns about the Middle East, and especially Syria, have displaced other threats.

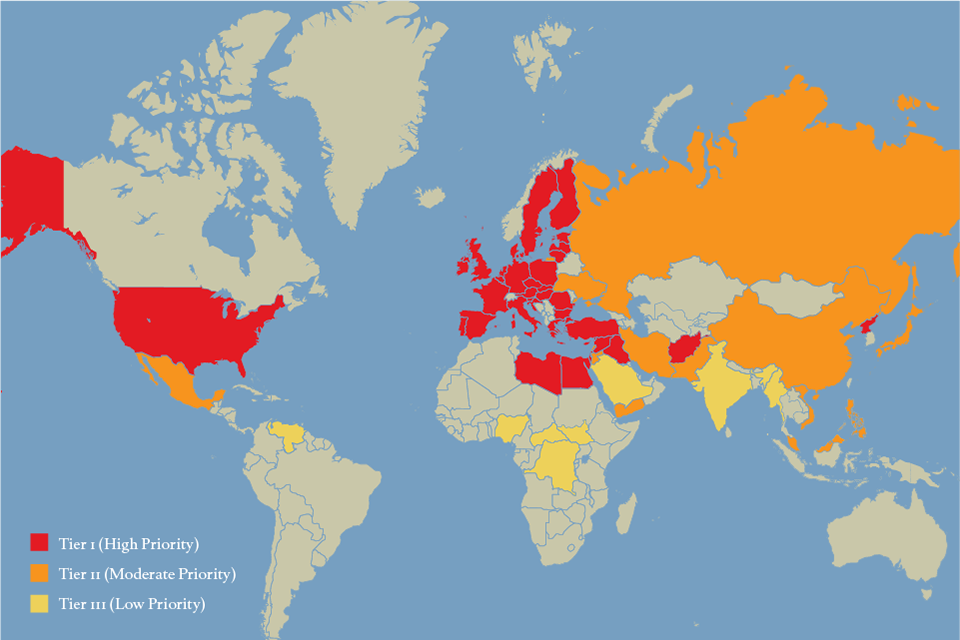

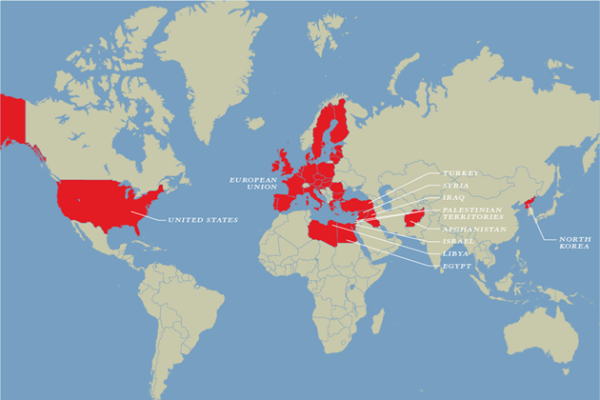

President Obama may believe America’s future lies in Asia, but the Middle East endures as the capital of American preoccupation. As Paul Stares, the report’s lead author, writes, “Of the eleven contingencies classified as Tier 1 priorities, all but three are related to events unfolding” in the Mideast. Several stem from the Syrian Civil War.

Two contingencies were downgraded from high to medium priorities between this year’s survey and last year’s, even though hostilities in each case are still pronounced: an armed confrontation between China and its neighbors over territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and an escalation in fighting between Russian-backed militias and Ukrainian security forces in eastern Ukraine.

A ceasefire in eastern Ukraine “seems to be holding,” Stares noted, “and Russia has a lot on its plate both internally and in terms of its [military] intervention into Syria. Why would they dial up tensions in Ukraine at this moment?” Similarly, “there’s probably a sense that China has made the island grabs that it wants to do, and it is consolidating its position [in the South China Sea]. And given China’s [sluggish] economic situation … and a certain level of high-level agreement between the U.S. and China with the various meetings between [Presidents] Xi and Obama, people are saying, ‘Look, I don’t think the Chinese are really going to rock the boat here this year.”

A third scenario—an intentional or unintentional military face-off between Russia and one or more NATO member states—appeared for the first time in the survey, in the second tier shown below. As for Iran, angst has shifted since 2014 from the country’s nuclear program, which was substantially restricted in July as part of an agreement with world powers, to its support of proxy militias in various Middle Eastern conflicts. This tranche of priorities also includes violence from organized crime in Mexico, destabilizing spillover from Syria to nearby countries, and China and Japan contesting the sovereignty of islands in the East China Sea.

Stares attributed Saudi Arabia’s presence on this year’s list to three factors: “I think it’s the combination of some reports of internal dissension within the Saudi royal family … reports of financial, economic, or budgetary difficulties in the Kingdom as a result of depressed oil prices and therefore depressed government revenues … and thirdly the Saudi [military] intervention in [the civil war in] Yemen, which has had some resonance within Saudi elites. I think there’s concern about whether Saudi Arabia may have overstretched itself there. And it’s unclear how this will end, and how much of a burden—and how much blowback—there might be.”

In Nigeria, where a new president was elected in March, turmoil related to the jihadist group Boko Haram was judged to be less of a risk than it was last year, even though Boko Haram remains the world’s deadliest terrorist organization. Also mentioned here were the prospects for a major clash between India and Pakistan and a more profound crisis in post-Chavez Venezuela, where the economy is in tatters and the opposition has won control of the legislative but not the executive branch. (Respondents wrote in their own conflicts as well, including territorial competition in the Arctic, fallout from the potential death of Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe, now 91, and possible mass atrocities in politically polarized Burundi, where 87 people were killed last Friday.)

In a recently released guide to the multi-sided conflict in Congo, the Council on Foreign Relations notes that for almost two decades, the country’s eastern provinces have been the site of the deadliest fighting since World War II. And the costs of that violence are staggering. CFR points out that Congo’s hydropower potential is greater than sub-Saharan Africa’s total current energy capacity, that its arable land could feed nearly all of Africa, and that its mineral wealth is critical to the world’s consumer electronics—but that much of this economic promise has yet to be realized. These natural resources have exacerbated the conflict, but they also highlight the huge upside to resolving it. Whether war ebbs depends in part on elections in November 2016, when President Joseph Kabila could either permit a democratic transition or flout the constitution and try to maintain his 15-year hold on power.

It’s quite a consequential moment for Congo. But judging by the maps above, it’s one that U.S. officials may not pay all that much attention to.