PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

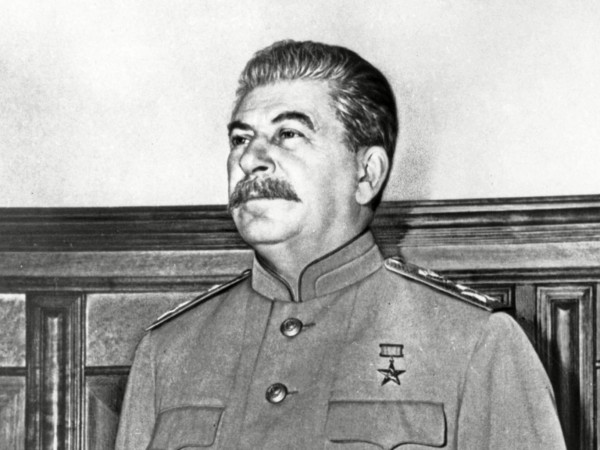

On Stalin’s Team by Sheila Fitzpatrick, book review: Uncle Joe’s henchmen

Mary Dejevsky | Thursday 22 October 2015 | The Independent

Sheila Fitzpatrick’s latest book comes with a central thesis that challenges the one fact about Soviet history that everyone in the Western world and beyond thinks they know: that Stalin was a dictator who ruled in a state of isolation created and reinforced by the “cult of personality”.

On Stalin’s Team is a largely successful attempt to show that in attaining power, exercising power, and gradually losing power as his faculties declined, Stalin was less a wilful tyrant and more the captain of a Kremlin team. Fitzpatrick tracks its early members and argues that it remained remarkably consistent – despite perpetually stormy times.

She maintains, further, that the idea of the Kremlin power-holders as a team, with the co-operation and give-and-take that presupposes, helps to explain why there was no dangerous power vacuum, either during Lenin’s final illness or after Stalin’s death. With a slight wobble on Stalin’s part after the German invasion of 1941, the team held together and carried on.

The conduct of that war, known in Russia as the Great Patriotic War, she judges to have been a high water mark of Stalin’s team leadership, in part because everything was directed towards the single objective of defending the country; in part because there was an effective division of labour at the very top.

Fitzpatrick makes a persuasive case. But there are times when she seems to protest the team concept just a bit too much. Directly or indirectly, she concedes that Stalin’s initiative was crucial to such costly and inhumane projects as forced collectivisation, the great purges, and the outbreak of anti-Semitism exemplified by the 1953 investigation into the alleged doctors’ plot. How much power was actually spread around?

You do not have to accept Fitzpatrick’s thesis in its entirety, however, to appreciate her portraits of the team members and the dynamic between them. She depicts Molotov, Mikoyan, Voroshilov and Khrushchev as great survivors, but also shows how their politics and social life were intertwined. The various “top” families knew each other well. Some were in and out of one another’s houses and dachas; others could not stand each other.

And even if she takes her central argument too far, Fitzpatrick’s book offers a salutary corrective. The West tends to view Russian leaders – from Ivan the Terrible to Vladimir Putin – as lone and largely malevolent tsars. If even Stalin was less of an autocrat than has generally been believed, and if – as the archives now suggest – Gorbachev’s leadership was far more transactional and contested than it appeared, might it not be time to stop equating modern Russian leaders with tsars, and consider the constraints on their power instead.

Princeton, £24.95. Order at the discounted price of £22.95 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop