PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

‘Let’s Go Take Back Our Country’

Stuart A. Reid | March 2016 Issue | THE ATLANTIC

What happened when 11 exiles armed themselves for a violent night in the Gambia

In the dark hours of the morning on December 30, 2014, eight men gathered in a graveyard a mile down the road from the official residence of Yahya Jammeh, the president of the Gambia. The State House overlooks the Atlantic Ocean from the capital city of Banjul, on an island at the mouth of the Gambia River. It was built in the 1820s and served as the governor’s mansion through the end of British colonialism, in 1965. Trees and high walls separate the house from the road, obscuring any light inside.

In the dark hours of the morning on December 30, 2014, eight men gathered in a graveyard a mile down the road from the official residence of Yahya Jammeh, the president of the Gambia. The State House overlooks the Atlantic Ocean from the capital city of Banjul, on an island at the mouth of the Gambia River. It was built in the 1820s and served as the governor’s mansion through the end of British colonialism, in 1965. Trees and high walls separate the house from the road, obscuring any light inside.

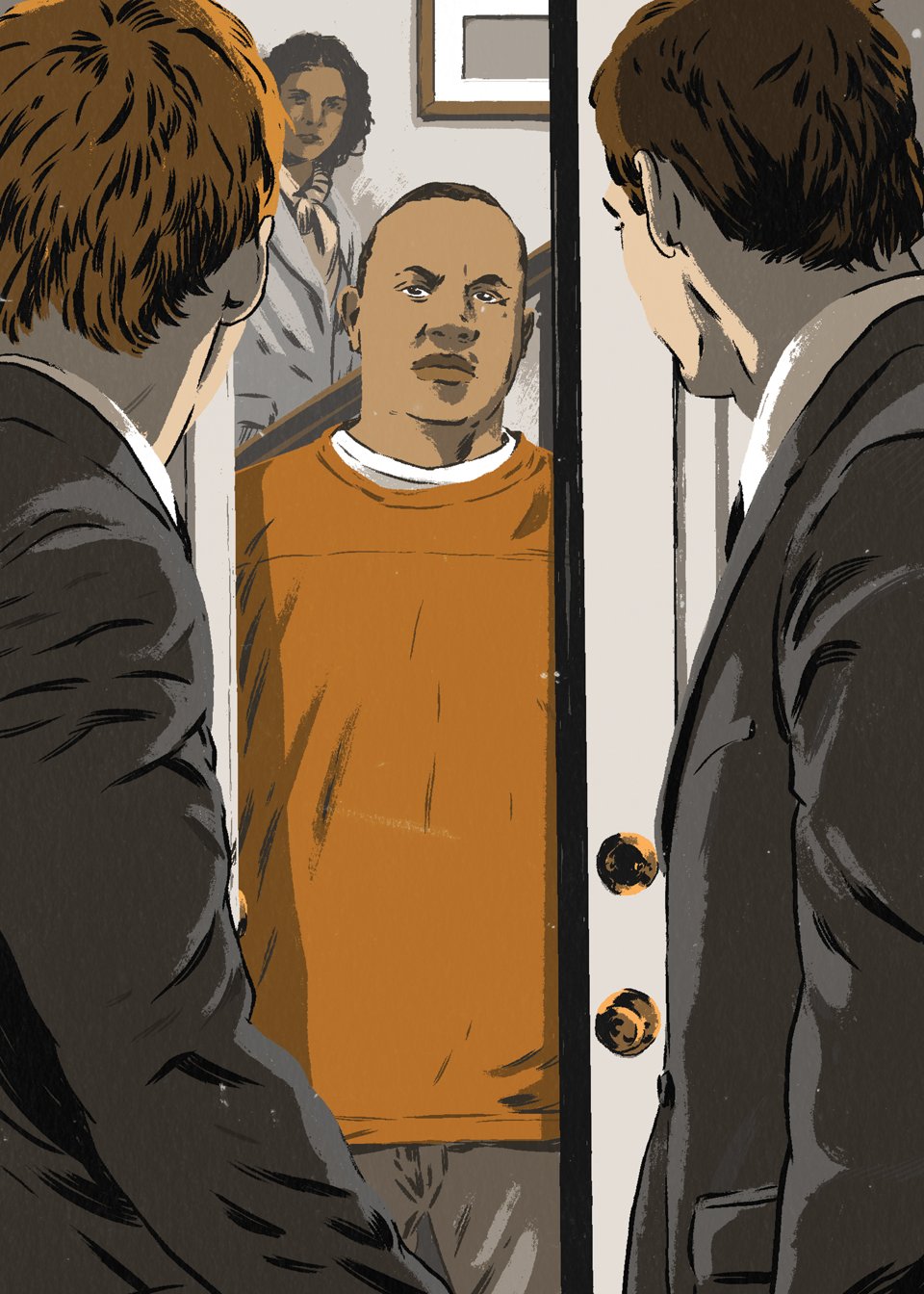

The men were dressed in boots and dark pants, and as two of them stood guard, the rest donned Kevlar helmets and leather gloves, strapped on body armor and CamelBaks, and loaded their guns. Their plan was to storm the presidential compound, win over the military, and install their own civilian leader. They hoped to gain control of the country by New Year’s Day.

The head of the group was Lamin Sanneh, a bulky 35-year-old who had commanded an elite military unit charged with protecting the president, until he had fallen out with Jammeh the year before and taken refuge in the suburbs of Baltimore, Maryland. To the men in the graveyard, Sanneh seemed perfectly suited to the mission. He had been trained at the best foreign military academies and was familiar with the inner workings of Jammeh’s security apparatus, from the armaments in the State House’s guard towers to the routes taken by the presidential motorcade.

“A banana shoved into the mouth of Senegal”—so goes the polite version of a local saying that describes the Gambia’s appearance on a map. The country, home to fewer than 2 million people, is a narrow strip of territory carved out of the banks of its namesake river. The Atlantic forms the western edge; Senegal surrounds the rest.

Weak borders and weak governments still characterize much of West Africa, and the coup d’état brewing in the graveyard would not be the Gambia’s first. Sanneh was on summer break from middle school in 1994 when, one morning, a group of junior army officers angry about their low salaries seized the national radio station, the airport, and government buildings in Banjul. The incumbent president, Dawda Jawara, who had led the country since independence, found safety on a docked U.S. warship while his guards evacuated the State House. When the disgruntled officers arrived, Andrew Winter, then the U.S. ambassador to the Gambia, told me, “I think much to their surprise, it was theirs.” At about 6 o’clock that evening, an announcement came on the radio: A four-member group called the Armed Forces Provisional Ruling Council, or AFPRC, had taken over. Its chair was Yahya Jammeh, then a 29-year-old army lieutenant who was little known outside the barracks.

Under Jawara, the Gambia had been a bright spot in post-independence Africa. From the start of decolonization, in the 1950s, until the end of his tenure, leaders in continental West Africa were more likely to be ousted by members of the military than to lose power in elections. During that period, the 14 other countries in the region together experienced 35 successful coups. But Jawara, over his three decades in office, fostered a multiparty democracy, tolerated a free press, and outlawed the death penalty. Before the AFPRC takeover, the Gambia was Africa’s longest-surviving democracy—and Jawara was the last of its hopeful crop of 1950s and ’60s nationalist leaders still in office.

A member of the Jola people—a small ethnic group that was the last in the region to convert to Islam—Jammeh stood out on the base for his extreme superstition. According to Sey, Jammeh claimed that he could cure fellow soldiers’ sprains just by touching them, and at night he would rub himself with leaves to ward off spirits. He also had a reputation as a small-time bully. At the base’s gate, he once made a pregnant visitor dance like a monkey until she fainted. After Jammeh locked Sey out of the dormitory one evening, Sey wrote Jammeh a letter calling him a dictator. “I am the first person who used that word for him,” Sey told me.

Military governments do military things, and the Gambia’s once-open society began to contract. The police, even when only on crowd-control duty at a soccer stadium, were armed with rifles and rocket-propelled grenade launchers. So perhaps it was inevitable that when a group of students gathered in April 2000 to protest the alleged rape of a teenage girl by a security officer, the police opened fire. At least 14 people were killed.

Nonetheless, in 2001, Jammeh won a second term. He was popular for the paved roads, hospitals, and schools his government had built. Classrooms, for once, were furnished; no longer did students have to lug their own desks and chairs to school. But while international observers declared the election “free and fair,” the political playing field was anything but level. Police raided journalists’ homes and arrested activists. Jammeh toured the country in a motorcade bristling with rocket launchers, reportedly distributing cash to the crowds that greeted him.

Jammeh feared the barracks more than the ballot—with good reason. The year after he took power, he had two members of his own party arrested for plotting countercoups, and caused a third to flee the country. Various schemers within the military launched unsuccessful coups in 1994, 1995, 2000, and 2006. After the 2006 attempt—allegedly led by the former chief of the defense staff—Jammeh announced a crackdown. “I will set an example that will put a definitive end to these ruthless, callous, and shameless acts of treachery and sabotage,” he said. “I have warned Gambians long enough.”

Jammeh also cultivated a special military force, bound to him through ethnic ties—another coup-proofing strategy. The unit, known as the State Guards, was charged with protecting the country’s most strategically valuable points: the State House; the president’s villa in Kanilai; and Denton Bridge, the sole roadway connecting the capital to the Gambian mainland. Jammeh filled its ranks with Jolas, his ethnic brethren.

Jammeh was thus putting Lamin Sanneh in a position of considerable trust when he made him commander of the State Guards, in July 2012. Perhaps the president saw himself in the young lieutenant colonel. Born in a rural village not far from Kanilai, Sanneh had joined the military out of high school and worked as an instructor at the same barracks Jammeh had. When the military opened a new training school in Kanilai, Sanneh was picked as its chief instructor.

Like Jammeh, Sanneh went abroad for military training, first to Sandhurst, in the United Kingdom, and then to the National Defense University, in Washington, D.C., as a counterterrorism fellow. He lived with his wife, Hoja, and two of their children in a condominium in Arlington, Virginia, where their lives revolved around Sanneh’s academic work. On weekend mornings, after cooking breakfast for the family, Sanneh would head to the condominium’s business center to write. When he tired of typing, Hoja took dictation.

In his master’s thesis, about drug trafficking in West Africa, Sanneh trod carefully when discussing the trade’s links to Gambian officials, making sure to cite pro-government newspapers as sources and to omit all mention of Jammeh. His adviser, Jeffrey Meiser, recalled that among the bright young officers from around the world, Sanneh had distinguished himself. At his graduation ceremony, as he shook hands with General Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Sanneh stood out in his red full dress, a gold aiguillette dangling from his chest.

He was right to worry. His problems began when his boss, General Saul Badjie—Jammeh’s closest military adviser—told him to fire subordinates without cause. When Sanneh refused, Badjie started looking into his background, and found out he was a Mandinka—the most prevalent of the Gambia’s ethnic groups, and a regular target of Jammeh’s sniping—despite hailing from a district with a high concentration of Jolas. In February 2013, just seven months after he had started, Sanneh was expelled from the State Guards and demoted to major. The next month, he was dismissed from the army. He wrote to Meiser, requesting a letter of recommendation—“urgently”—for a master’s program in Taiwan.

Sanneh soon learned from neighbors that his house appeared to be under surveillance, and not long after, he got word that he should leave the Gambia immediately. He fled with his wife and children to Dakar, Senegal. Even there, he did not feel safe—an online radio station had announced that Jammeh’s men were looking for him—so he applied for refugee status at the American Embassy, and in the summer of 2013 he resettled with his family near Baltimore.

As an exile and a prominent critic of Jammeh, Manneh was used to being approached by leaders of far-fetched coup plots, and he always turned them down. But Sanneh was insistent: Peaceful resistance would never do the trick. Jammeh must be overthrown. When Manneh got a similar call from Njaga Jagne, a high-school acquaintance who had left the Gambia 20 years earlier, he decided to put the two men in touch.

The group of would-be revolutionaries soon grew to include two more expatriates, both of whom had served in the U.S. Army. They called themselves the Gambia Freedom League.The men started holding hour-long conference calls every other Saturday evening. At first, these were relaxed affairs, filled with jokes about hometown rivalries. The members who had served in the military, and possessed the sense of punctuality to match, playfully scolded Manneh for joining the calls late. They eventually adopted code names: “Fox,” “Dave,” “Bandit,” “X.”

By the late summer of 2014, the Gambia Freedom League had added a recruit from Seattle and a U.S. Army veteran from Minneapolis named Papa Faal. Dawda Jawara, the ousted president of the Gambia, was Faal’s great-uncle, and during a failed coup attempt in 1981—which took place while Jawara was in London for the wedding of Prince Charles and Princess Diana—a 13-year-old Faal was held hostage at gunpoint with his family. In a memoir published in 2013, he had inveighed against the leaders of the plot, claiming that coups sow “the seeds of a future conflict or coup.” But like the others, Faal had concluded that nonviolent methods of removing Jammeh had run their course.

Now, on the biweekly conference calls, Sanneh laid out a detailed blueprint for capturing or killing Jammeh. “Chuck,” as the plan referred to him, would be removed in one of four ways. The first three involved roadside ambushes at various points that Jammeh’s motorcade was known to pass. The group assumed that the lead vehicle would be disabled with a .50-caliber sniper rifle. Then the convoy would halt and the fighters would persuade the presidential bodyguards to drop their weapons.

But if all went according to plan, Cherno Njie, waiting safely away from the action, would call up the commander of the Gambian military and persuade him to join their cause. Then the military would secure the airport, power plants, ports, and border posts. Gamtel, the national telecom company, would also be taken over, and cellphone service would be shut down to disrupt communication within the regime. Once the state radio and television services were in friendly hands, the new government would be announced on the airwaves, with Manneh serving as its international spokesman. It would be a classic bloodless coup.

The operation may have had a whiff of naïveté, but it was certainly better organized than the coup that had brought Jammeh to power, the planning of which, by some accounts, had begun only the night before.

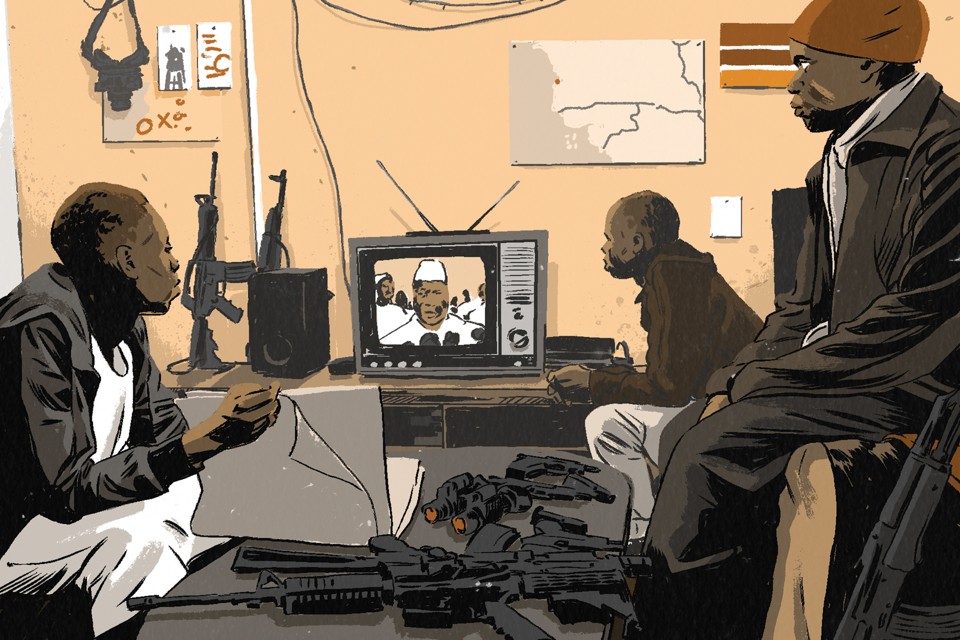

The coup would require considerable firepower—which the men could acquire legally in America. A spreadsheet they kept called for 28 rifles, eight pistols, four machine guns, and 15 sights. In a row listing two .50-caliber sniper rifles was a note: “NOT really necessary but could be very useful” (the group ended up splurging on them). Faal bought eight M4 semiautomatic rifles, splitting the purchases between two different gun dealers in Minneapolis. Jagne and Alagie Barrow, one of the Army veterans, also bought at least eight weapons each, including three Smith & Wesson rifles that Barrow picked up from a gun store near his house in Tennessee.

To get the equipment to the Gambia, the men would ship it in barrels under false names that sounded Jola, which they believed would reduce the chances of inspection. After one member of the group arranged a successful test shipment of two weapons, Faal broke down his eight rifles in his garage. He put the parts inside cardboard boxes, which he slid into plastic barrels and concealed with blankets, T‑shirts, and shoes from Goodwill. He brought the barrels to a local shipping company and sent them off to the port of Banjul.

In late October, Alagie Barrow flew to Dakar, half a day’s drive from the Gambia’s northern border, to act as an advance man. The others tied up their lives in America. Njaga Jagne let his ex-wife know that he would be out of town for a few weeks and tried, unsuccessfully, to rearrange their custody schedule to get extra days with their 9-year-old son. Papa Faal told the community college where he was teaching that he would be taking the next semester off, and set up his bills for automatic payment. His wife happened to be planning to take their infant daughter to the Gambia in December to see family; he tried to change her mind but gave up when she grew suspicious. He deflected questions about his own travel plans by saying he was going on a business trip.

The other members were less successful. According to Manneh, after the recruit from Seattle told his wife he was going to the Gambia, she told his mother, and his mother confiscated his passport and made him cancel his plane ticket. The remaining U.S. Army veteran also bailed.

Manneh would not be joining the group in Africa either. He had discovered that Njie had put together his own transition plan, in which Manneh would not serve as the group’s spokesman. Manneh confided his concerns about the change to Sanneh, who would hear none of it. Soon, Manneh was excluded from the conference calls.

A sprawling, cacophonous city with flights volleying in from Europe and North America, Dakar is a fitting place to muster an international crew to overthrow an African government. In late December, at a budget guesthouse on the outskirts of the city, Sanneh assembled five former soldiers who had also fallen out of favor with President Jammeh. After trying in vain for a few days to expand the team—and joining up with Cherno Njie—they headed for the Gambia, where one more expatriate would meet them. They traveled light and crossed the border separately; those who risked being recognized avoided checkpoints.

Everyone expected Jammeh to come out of his house on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day, at which point they could lay an ambush. But he never did, and the day after Christmas, a Friday, Sanneh learned that Jammeh would be leaving the country early the next morning. That night, the group gathered at one of the safe houses to prepare for an ambush near Denton Bridge. As they geared up, however, Sanneh was told by one of his sources that Jammeh’s departure had been pushed back to 10 a.m. The timing would rob them of the cover of darkness, and risk civilian casualties among the crowds that would inevitably line up to cheer on the presidential motorcade. Sanneh called off the attack.

On Sunday, Sanneh told the group that he had a new plan: Another ally in the military, a captain, would meet with them late that night outside Banjul and join them in securing the State House. Once again, the group gathered at a safe house and waited. Once again, they had to abort. The captain was not answering Sanneh’s phone calls. Morale was low, and some privately doubted that Sanneh had the support he said he did. He told the men to go to bed.

Most slept late on Monday. Some showered or sipped tea. At the dining-room table of the safe house where he was staying, Sanneh met with some of the other members of the Gambia Freedom League to debate whether to attack the State House, where General Badjie stayed when Jammeh was away. One of the men Sanneh had summoned to Dakar, a former army captain named Mustapha Faal (no relation to Papa Faal), thought it insane to try to take the State House with so few men. “I’m not here to commit suicide,” he said.

Sanneh pushed back. Every extra day the men hid in the Gambia, the odds that they might be discovered grew. Calling off the mission would mean not only throwing away more than a year and a half of planning, but also failing those inside the regime whom Sanneh had persuaded to join the riskiest venture of their lives. More practically, Sanneh faced pressure from Cherno Njie, the would-be president, who, as a businessman rather than a soldier, was uncomfortable living among so many weapons and wanted to act quickly.

They made it past the Denton Bridge checkpoint before 7 p.m., when the more scrutinous military would take over from the police. With hours to kill, they drove aimlessly through the streets of Banjul, stopping for Coca-Cola, goat meat, and evening prayers. A New Year’s festival was taking place, and they distracted themselves with the masked dancers and drummers.

Around 1 a.m., as the moon sank below the horizon, the cars turned into the graveyard. Sanneh announced two surprises. First, General Badjie was not at the State House, but more than 20 miles south, closer to the Senegalese border. Not to worry, he said. Soldiers were standing by at the State House and near the airport, ready to help seize power. Second, Sanneh introduced a last-minute recruit, who stepped out of the woods: a young Gambian soldier who would go by the code name “Junior.” By now, everyone realized that Mustapha Faal had abandoned the group.

Sanneh would head up team Alpha, attacking the front gate of the compound along with Junior, Lowe, Jagne, and a young man named Modou Njie (no relation to Cherno Njie), who had worked as Sanneh’s aide at the State House. Papa Faal and two former Gambian soldiers, Alagie Nyass and Musa Sarr, would make up team Bravo, attacking from the rear. With fewer men than expected, there would be no team Charlie.

As some of the men later recounted, Alpha and Bravo each got into a car and drove toward the State House—windows up, headlights off. When Alpha reached the outer entrance, everyone but Modou Njie got out of the car. Lowe raised his gun at two scared sentries at a guard post. “We’re not going to kill you,” he said. “Drop your guns.” They complied. Sanneh radioed the news to Bravo. Then Njie rammed the car through a series of barriers, getting deep inside the compound.

Within moments, Lowe heard another shot—fired, he suspected, by the same guard—and watched as Sanneh crumpled to the ground. Lowe tried to drag his body to safety, but it was too heavy. Nor could he get Sanneh’s phone, which contained all his communications with the government insiders. The bullets were still coming.

When the men in Bravo heard the gunfire, their car was pulling up next to the back gate of the State House, where the team was supposed to ensure that the soldiers fleeing Alpha’s assault left unarmed. Before the car could stop, it started taking shots from a guard tower. “Get out!” yelled Sarr. He and Faal fired at the tower—Faal with one of the .50-caliber rifles—but in the darkness, it was hard to know where to aim. It sure would be nice to have night-vision goggles, Faal thought to himself.

Nyass drove the car toward the gate, intending to burst through it; a blast of gunfire from the tower stopped him. As he climbed out of the car, he was met with a hail of bullets. Sarr, whose boot had been grazed and whose body armor had taken a direct shot, radioed Alpha to report that Nyass had been killed. He heard only static in response. He and Faal decided it was time to flee.

Faal entered the courtyard of a hospital neighboring the State House, took off his vest, and laid his rifle next to a tree. He sliced off his cargo pockets with his knife to make his pants look less like combat gear, and crouched behind a concrete wall to wait for morning.

Sarr jumped a fence and headed for the beach. Pretending to be a guard looking for the intruders, he pointed his rifle left and right as he ran. He waded into the ocean to hide, later burying his weapons in the sand and escaping Banjul.

On the other side of the State House, with Sanneh dead, the remnants of Alpha also decided to retreat. Modou Njie had become separated from the group. When Lowe reached him by cellphone, he said he had made it into the office of the commander of the State Guards. Everyone inside was confused. Lowe told him to come back to the outer gate.

When Modou Njie didn’t show up, Lowe called again, but someone else answered. “Where are you guys?” a man asked. Lowe recognized the voice of the current commander of the State Guards. Thinking quickly, Lowe answered that rebel reinforcements had arrived and were waiting to slaughter anyone who left. The gambit bought him enough time to escape. He lost track of the others. Junior, he would later learn, also managed to get out safely. But Modou Njie was captured, and at some point during the chaos, Jagne was killed.

Lowe hopped over the State House fence, stripped off his armor, and threw down his gun. Troops were gathering on the nearby beach. He caught a taxi and instructed the driver to head across Denton Bridge. At the checkpoint, Lowe recognized some of the soldiers, but they seemed not to notice him. A small bribe to expedite the process, and the car was through.

Lowe’s taxi made its way toward Senegal. At another checkpoint, the police asked the driver to give a ride to a soldier. For the 10 miles the soldier was in the car, Lowe pretended to sleep in the backseat. When the driver dropped Lowe off near the border, Lowe gave him 50 euros and told him not to tell anyone what he’d seen.

Back at the safe house, Cherno Njie was waiting for news with Alagie Barrow and Dawda Bojang. Their radio had not picked up any signal from the group. But then they got a call from Lowe, informing them that the operation had been aborted. They tossed some weapons in their car and took a back road across the Senegalese border. As they escaped, Barrow called Banka Manneh in Atlanta. It was the first Manneh had heard from him in some time. “This thing failed,” Barrow said. Sanneh and Jagne, he added, “couldn’t make it.” Manneh would later learn that Nyass had also been killed.

The day after the attack, the names of the dead began to circulate on online radio stations and on Facebook. At home in Maryland, Sanneh’s widow, Hoja, refused to believe that her husband had taken part in the coup, never mind that he was dead. She tried calling and texting Sanneh, and even logged in to his Verizon account to see his cellphone records. She turned to Manneh for help, knowing that he talked frequently with her husband. When he tried Sanneh’s number, someone who claimed to be a cousin answered, asking Manneh to leave a message because Sanneh was “quite busy right now.” The phone had been taken by the National Intelligence Agency.

Hours after the attempted coup, Banjul awoke to a military lockdown. The streets crawled with soldiers moving from house to house in search of hidden attackers. New checkpoints appeared. Businesses closed. A fire truck was summoned to the State House to hose blood off the concrete.

When Papa Faal, still hiding in the courtyard, heard the call to prayer, he approached a hospital visitor and persuaded him to swap clothes. He put on the man’s jeans, flip-flops, and dirty undershirt and slipped into the streets of Banjul. He was still unsure whether the coup had succeeded or failed—maybe Sanneh’s promised reinforcements had shown up after all—until he walked back to the State House and saw a white body bag being carried out and the vice president’s silver car arriving. The regime was intact. State radio played traditional music, and the government released a statement: “Contrary to rumors being circulated, peace and calm continue to prevail in the Gambia.”

Denton Bridge was shut down, as was a ferry that provided the only other way back to the mainland. Faal wandered around the city, trying not to make too much or too little eye contact with the soldiers he passed on the street. He wished he had the anti-anxiety pills he had been prescribed for post-traumatic stress disorder after he came back from Afghanistan. With the port still closed, he stayed the night at the house of a man he befriended at a mosque.

The next morning, the ferry started running again, and Faal took it to the north bank of the Gambia River before riding in shared taxis—at one point, like Lowe, seated next to a Gambian soldier—all the way back to Dakar. When other passengers gossiped about a terrorist attack in Banjul, he kept quiet.

It was nearly midnight on New Year’s Eve when Faal arrived, and the American Embassy was closed. Frantic, he waved down a guard. “I’m a U.S. citizen,” he said. “I need to talk to somebody inside.” He was led into the embassy and introduced to a State Department official and an FBI agent. They gave him a slice of pizza and a bottle of water as he told them everything. “You know this is a crime, right?” the agent asked.

“It only takes one conspirator to betray a conspiracy,” cautions How to Stage a Military Coup, a book that Alagie Barrow kept in his house. Had the Gambia Freedom League been betrayed?

Papa Faal thought so. The tower that fired at Bravo team, he said, was staffed with more guards than usual. Word of the attack could have been leaked by one of Sanneh’s intended recruits, or by someone in the Gambian diaspora, where—despite the men’s careful planning—rumors of an impending coup had been circulating for weeks. Two weeks before the attack, Pa Nderry M’Bai, a Gambian radio host based in North Carolina, posted a picture of Jammeh for his thousands of Facebook followers with the caption “Something big is brewing.”

A warning could also have come through more-official channels. In May 2015, The Washington Post revealed that the FBI had notified the State Department of Sanneh’s suspicious travel plans, and the State Department had passed on the information to “authorities in a West African country near Gambia”—read: Senegal. But two Senegalese foreign-policy officials I spoke with flatly rejected the idea that their government would tip off Jammeh. Relations with the Gambia are so hostile, one said, that Senegal would be happy to see him ousted. “But of course we can’t admit that,” he added.

Bai Lowe told me that everyone he encountered at the State House seemed surprised. Had the regime known about the attack in advance, he argued, the group would never have been able to make it through the checkpoints into Banjul, let alone disarm two sentries. Perhaps the ultimate cause of the coup’s failure was not what the Gambian military knew about Sanneh, then, but what Sanneh thought he knew about the Gambian military. “He believed all these army boys were so tired of Jammeh that any day anything like this started, whether they knew about it or not, they would be happy to join the other side,” Banka Manneh said. “I think he had convinced himself of that.”

After papa faal returned to the U.S., the FBI arrested him, along with Cherno Njie and Alagie Barrow (both of whom declined to be interviewed for this article). The FBI also picked up Manneh. Each man faces up to five years in prison for conspiring to violate the Neutrality Act, a 1794 law that bars U.S. citizens from taking up arms against any foreign country with which the United States is at peace, and up to 20 years for buying weapons to do so. Faal, Barrow, and Manneh have pleaded guilty and are awaiting sentencing. As of this writing, Cherno Njie has not entered a plea.

Bai Lowe and Dawda Bojang both returned home to Germany, where they are awaiting the results of their asylum applications. When I met Lowe in Hannover, in May, he refused to eat or drink in public, fearful that he might be poisoned; he had heard that one of Jammeh’s agents was in the country looking for him.

Inside the Gambia, the crackdown was expansive. The government rounded up relatives of Gambia Freedom League members, including Sanneh’s elderly mother and Lowe’s 16-year-old son, and jailed them without charges. Lowe told me that Gambian police even showed up at his 7-year-old daughter’s school, in a border town in Senegal. The headmistress scared them off by calling the gendarmerie. A Gambian court-martial convicted six soldiers for their roles in the coup attempt—Modou Njie (who had been captured at the State House), four of the insiders Sanneh had been courting, and one soldier accused of displaying cowardice before the enemy. Njie and two others were sentenced to death. As for the three men killed in the attack, the Gambian government never released their bodies, although pictures of their bloodied corpses surfaced online.

In January, Banka Manneh drove from Atlanta to a mosque in Maryland to pay his respects to Sanneh’s family. He recited the Koran and prayed with Sanneh’s friends and relatives. Hoja, Sanneh’s widow, wore a traditional white mourning dress.

“People still ask me, ‘Why did he go?,’ ” Hoja told me. “He had a bright future here. He had a family here. He had everything he needed. Why would he even go? I don’t have the answer to that.”

When i visited the Gambia last summer, life seemed to have returned to normal. But according to opposition leaders, the coup attempt had done lasting damage. Ousainou Darboe, the head of the United Democratic Party, told me that Jammeh had used the attack to justify more repression. “Any efforts to change the regime by extralegal means take us three steps backward,” he said. Darboe suspected that the National Intelligence Agency had put the opposition under increased surveillance. He’d noticed a suspicious phone-card vendor and other “strange faces” showing up near his house.

I met O. J. Jallow, a former agriculture minister under Dawda Jawara and now the leader of the People’s Progressive Party, in his living room. He knew some of the plotters, and was baffled by their involvement. “I don’t know what convinced them that the military strategy is more effective than the peaceful democratic process,” he said.

Jallow had been arrested 20 times since Jammeh took power, and his left eye was still injured from a beating he’d taken during one of those arrests. Even so, he believed that Jammeh was vulnerable. A drought, combined with the effects of the nearby Ebola epidemic on tourism, had devastated the Gambia’s already meager economy, driving citizens to emigrate in record numbers. Given the widespread discontent, he predicted, Jammeh could lose the next presidential election, which is scheduled for December, and be forced by the international community to step down.

One Western diplomat in Banjul scoffed at that notion. More likely, in his view, was that the president would finally fall to a luckier band of revolutionaries. “At some point,” he said, “someone will get it right.”

In July, President Jammeh, in what he advertised as a gesture of goodwill, let more than 200 prisoners out of Mile 2, including the family members of the Gambia Freedom League. The next week, the government held a “solidarity march” featuring some of the released prisoners, which began in front of Arch 22, a dilapidated monument in Banjul commemorating the coup that brought Jammeh to power. It was the rainy season, and supporters milled about with green umbrellas emblazoned with his party logo; the less fortunate stood in soaked T-shirts printed with his face. A marching band played, arms swinging in unison. A Toyota pickup truck mounted with a machine gun drove around in circles.

As the parade made its way down Independence Drive, I followed at a distance. Behind me, I heard a thunder of footsteps and teenage shouts: the youth wing of Jammeh’s party, rushing to join the rally. They had known no other president, and their devotion appeared unconditional. One girl’s shirt read we will do it for jammeh again & again.

A number of Gambian officials appeared at the event, but noticeably absent was Jammeh himself. Since the coup attempt, he has curtailed his public appearances and made no known foreign trips. He remains in the State House.