PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

The Cost of the Cultural Revolution, Fifty Years Later

In 1979, three years after the end of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping visited the United States. At a state banquet, he was seated near the actress Shirley MacLaine, who told Deng how impressed she had been on a trip to China some years earlier. She recalled her conversation with a scientist who said that he was grateful to Mao Zedong for removing him from his campus and sending him, as Mao did millions of other intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution, to toil on a farm. Deng replied, “He was lying.”

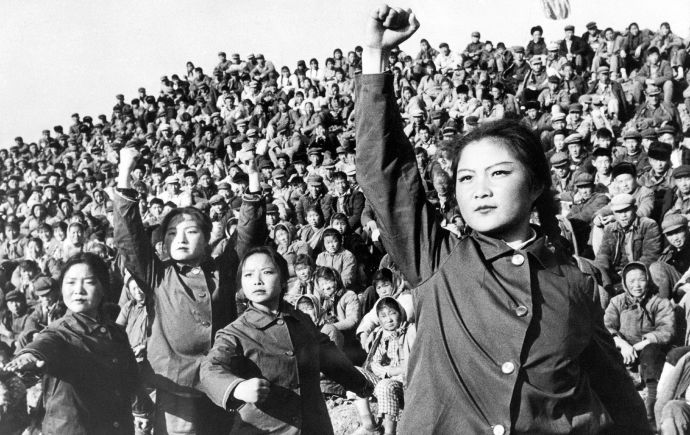

May 16th marks the fiftieth anniversary of the start of the Cultural Revolution, when Chairman Mao launched China on a campaign to purify itself of saboteurs and apostates, to find the “representatives of the bourgeoisie who have sneaked into the Party, the government, the army, and various spheres of culture” and drive them out with “the telescope and microscope of Mao Zedong Thought.” By the time the Cultural Revolution sputtered to a halt, there were many ways to tally its effects: about two hundred million people in the countryside suffered from chronic malnutrition, because the economy had been crippled; up to twenty million people had been uprooted and sent to the countryside; and up to one and a half million had been executed or driven to suicide. The taint of foreign ideas, real or imagined, was often the basis for an accusation; libraries of foreign texts were destroyed, and the British embassy was burned. When Xi Zhongxun—the father of China’s current President, Xi Jinping—was dragged before a crowd, he was accused, among other things, of having gazed at West Berlin through binoculars during a visit to East Germany.

In examining the legacy of the Cultural Revolution, the most difficult measurement cannot be quantified so precisely: What effect did the Cultural Revolution have on China’s soul? This is still not a subject that can be openly debated, at least not easily. The Communist Party strictly constrains discussion of the period for fear that it will lead to a full-scale reëxamination of Mao’s legacy, and of the Party’s role in Chinese history. In March, in anticipation of the anniversary, an editorial in the Global Times, a Party tabloid, warned against “small groups” seeking to create “a totally chaotic misunderstanding of the cultural revolution.” The editorial reminded people that “discussions strictly should not depart from the party’s decided politics or thinking.”

Nonetheless, in recent years, individuals have tried to reckon with the history and their roles in it. In January, 2014, alumni of the Experimental Middle School of Beijing Normal University apologized to their former teachers for their part in a surge of violence in August, 1966, when Bian Zhongyun, the deputy principal, was beaten to death. But such gestures are rare, and outsiders often find it hard to understand why survivors of the Cultural Revolution are loath to revisit an experience that shaped their lives so profoundly. One explanation is that the events of that period were so convoluted that many people feel the dual burdens of being both perpetrators and victims. Earlier this year, Bao Pu, a book publisher raised in Beijing and now based in Hong Kong, said, “Everyone feels he was a victim. If you look at them, you wonder, What the fuck were you doing in that situation? It was everyone else’s fault? You can’t blame everything on Mao. He was responsible, he was the mastermind, but in order to reach that level of social destruction—an entire generation has to reflect.”

China today is in the midst of another political fever, in the form of an anti-corruption crackdown and a harsh stifling of dissenting views. But it should not be mistaken for a replay of the Cultural Revolution. Even with thousands under arrest, the scale of suffering is of a different order, and shorthand comparisons run the risk of relieving the Cultural Revolution of its full horror. There are tactical differences as well: instead of unleashing the population to attack the Party, as Mao did in his call to “bombard the headquarters,” Xi Jinping has swung in the direction of tighter control, seeking to fortify the Party and his own grip on power. He has reorganized the top leadership to put himself at the center, suffocated liberal thinking and the media, and, for the first time, pursued critics of his government even when they are living outside mainland China. In recent months, Chinese security services have abducted opponents from Thailand, Myanmar, and Hong Kong.

And yet there are deeper parallels between this moment in China and the time in which Xi came of age, as a teen-ager in the Cultural Revolution, which illuminate just how enduring some of the features of Mao’s Leninist system have proved to be. Xi, in his constant moves to identify enemies and eliminate them, has revived the question that Lenin considered the most important of all: “Kto, Kovo?”—“Who, whom?” In other words, in every interaction, the question that matters is which force wins and which force loses. Mao and his generation, who grew up amid scarcity, saw no room for power-sharing or for pluralism; he called for “drawing a clear distinction between us and the enemy.” “Who are our enemies? Who are our friends?” This, Mao said, was “a question of first importance for the revolution.” China today, in many respects, bears little comparison with the world that Mao inhabited, but on that question Xi Jinping is true to his roots.

That zero-sum view is distorting China’s relations with the outside world, including with the United States. It was easy to laugh off the news last month that China had marked “National Security Education Day” by releasing a poster that warns female government workers about the dangers of dating foreigners, who could turn out to be spies. The cartoon poster, called “Dangerous Love,” chronicled the hapless romance of Little Li, a Chinese civil servant, who falls for David, a red-headed foreign scholar, only to end up giving him secret internal documents. Other recent news has been cause for concern: in April, after years of warnings, from senior leaders, that foreign N.G.O.s might seek to pollute Chinese society with subversive Western political ideas, China passed a law to sharply control their activities. The law gives sweeping new powers to China’s police in monitoring foundations, charities, and advocacy organizations, some of which have operated in China for decades. Many N.G.O.s had warned that the law, if passed, would cripple their ability to function, and they are now considering whether they can operate under the new arrangement.

As China, fifty years after the Cultural Revolution, weighs the impulse to insulate itself, once again, from foreign influence, it is worth considering that the costs may be more severe than we appreciate in real time. This fall, Harvard University Press will publish a new history, “Unlikely Partners: Chinese Reformers, Western Economists, and the Making of Global China,” by Julian Gewirtz, a doctoral student at Oxford. The book tells the little-known story of how Chinese intellectuals and leaders, facing a ruined economy at the end of the Cultural Revolution, sought the help of foreign economists to rebuild. Between 1976 and 1993, in a series of exchanges, conferences, and collaborations, Western intellectuals sought not to change China but to help it change itself, and they made indispensible contributions to China’s rise as a global economic power. “China’s rulers were in charge of this process—they sought out Western ideas and did not copy them indiscriminately. But they were open to Western influence and were profoundly influenced,” Gewirtz told me. “This history should not be forgotten. And, at a moment when China’s economy and society may be teetering, a return to this openness and partnership with the West—rather than the turn toward intellectual isolation and international distrustfulness that seems to be under way—is the best means of avoiding disaster.”