PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

American Hunger

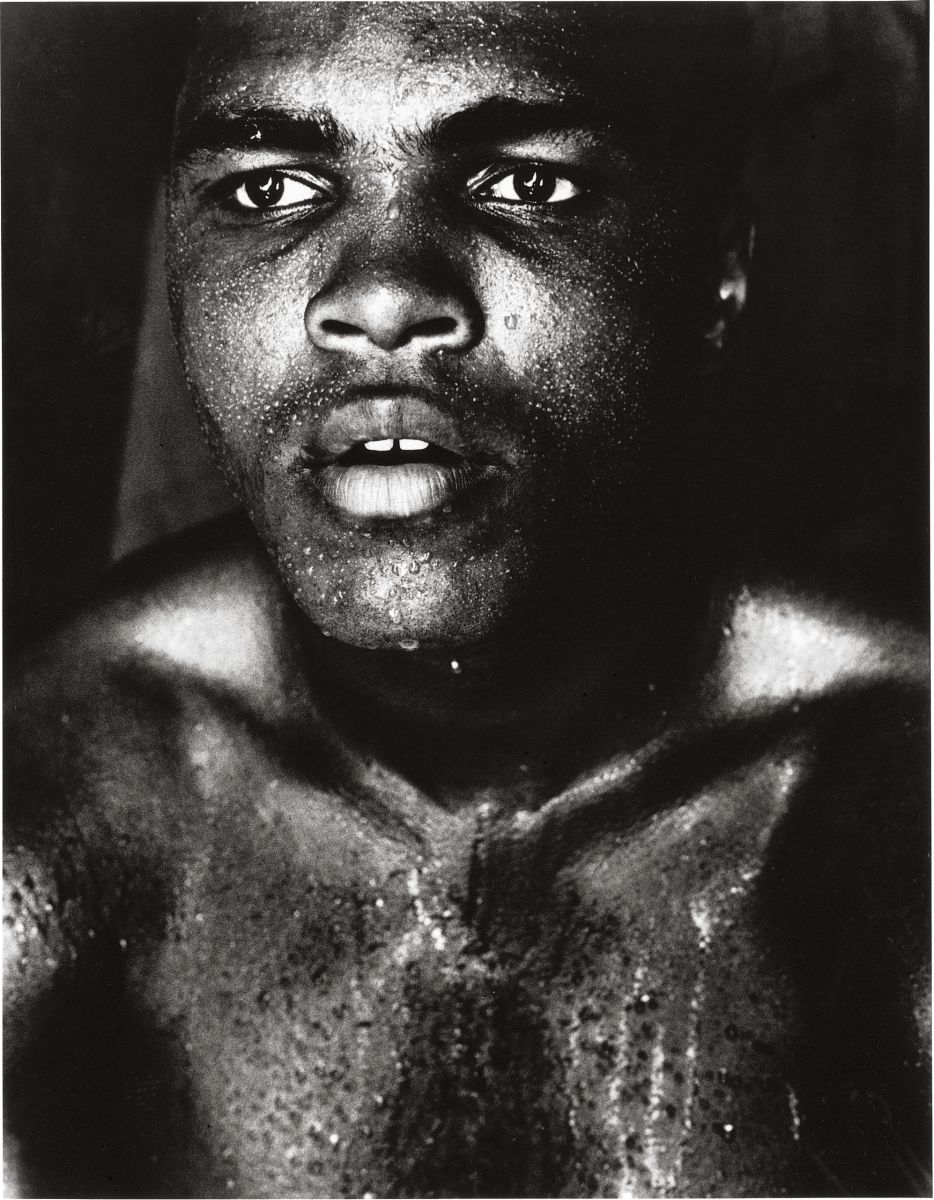

As an ambitious, searching young man, Cassius Clay invented himself, and became the most original and magnetic athlete of the century—Muhammad Ali.

On the night of February 25, 1964, Cassius Clay entered the ring in Miami Beach wearing a short white robe, “The Lip” stitched on the back. He was fast, sleek, and twenty-two. But, for the first time in his life, and the last, he was afraid. The ring was crowded with has-beens and would-bes, liege men and pugs. Clay ignored them. He began bouncing on the balls of his feet, shuffling joylessly at first, like a marathon dancer at ten to midnight, but then with more speed, more pleasure. After a few minutes, Sonny Liston, the heavyweight champion of the world, stepped through the ropes and onto the canvas, gingerly, like a man easing himself into a canoe. He wore a hooded robe. His eyes were unworried, and they were blank, the dead eyes of a man who’d never got a favor out of life and never given one out. He was not likely to give one to Cassius Clay.

Nearly every sportswriter in Miami Beach Convention Hall expected Clay to end the night on his back. The young boxing beat writer for the Times, Robert Lipsyte, got a call from his editors telling him to map out the route from the arena to the hospital, the better to know the way once Clay ended up there. The odds were seven to one against Clay, and it was almost impossible to find a bookie willing to take a bet on him. On the morning of the fight, the Post ran a column written by Jackie Gleason, the most popular television comedian in the country, which said, “I predict Sonny Liston will win in eighteen seconds of the first round, and my estimate includes the three seconds Blabber Mouth will bring into the ring with him.” Even Clay’s financial backers, the mandarin businessmen of the Louisville Sponsoring Group, expected disaster, perhaps physical harm; the group’s lawyer, Gordon Davidson, negotiated hard with Liston’s team, assuming that this could be the young man’s last night in the ring. Davidson hoped only that Clay would emerge “alive and unhurt.” At ringside, Malcolm X, Clay’s guest and mentor, settled into Seat No. 7. Gleason and Sammy Davis, Jr., were nearby, and so were the mobsters from Las Vegas, Chicago, St. Louis, New York. A cloud of cigar smoke drifted through the ring lights. Cassius Clay threw punches into the gray floating haze and waited for the bell.

“See that? See me?” More than thirty years later, Muhammad Ali sat in an overstuffed chair watching himself on the television screen. His voice came in a swallowed whisper and his finger waggled as it pointed toward his younger self, his self preserved on videotape: twenty-two years old, getting warm in his corner, his gloved hands dangling at his hips. Today, Ali lives in a farmhouse in Berrien Springs, a small town in southwestern Michigan. The rumor has always been that Al Capone owned the farm in the twenties. One of Ali’s dearest friends, his late cornerman Drew (Bundini) Brown, once searched the property hoping to find Capone’s buried treasure. He found beans.

Now Ali was whispering again, pointing: “See me? You see me?” And there he was, flanked by his trainer, Angelo Dundee, and Bundini, moonfaced and young and whispering hoodoo inspiration in Ali’s ears: “All night! All night! Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee! Rumble, young man, rumble!”

“That’s the only time I was ever scared in the ring,” Ali said. “Sonny Liston. First time. First round. Said he was gonna kill me.”

Ali was heavy now. He had the athlete’s disdain for exercise, and he ate more than was good for him. His beard was gray, and his hair was going gray, too. Ali is a man who has all his life lived in the moment, thrilling to the moment, its comedy and battle, its sex and adulation, and it is only now, in late middle age, in the grip of illness, that he has had the time and the patience to make sense of what he was and what he has left behind, to think about how a gangly kid from segregated Louisville willed himself to become one of the great original improvisers in American history, a brother to Davy Crockett, Walt Whitman, Duke Ellington. Even before he could vote, he consciously drew on influences as disparate as Sugar Ray Robinson and Gorgeous George, Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X, and yet he was utterly, and always, himself: “Who made me is me,” he insisted. As Cassius Clay, he entered the world of professional boxing at a time when the expectation was that a black fighter would defer to white sensibilities, that he would accede to the same mobsters who ran Liston, that he would play the noble and grateful warrior in the world of Southern Jim Crow and Northern hypocrisy. As an athlete, he was supposed to remain aloof from the racial and political upheaval going on around him: the student sit-ins in Nashville, the Freedom Rides, the March on Washington, the student protests in Albany, Georgia, and at Ole Miss. Clay not only responded to the upheaval but responded in a way that outraged everyone, from the White Citizens Councils to the leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He changed his religion and his name; he declared himself free of every mold and expectation. He showed boundless courage; he made foolish mistakes. He was an enemy, a figure of scorn, long before he was a focus of admiration and love. He was himself. Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali. Who made me is me.

As we watched the tapes that afternoon, Ali and I talked about the three leading heavyweights of the time—Floyd Patterson, Sonny Liston, and Clay himself—and the uncanny way they seemed to mark the political and racial changes going on just as they were fighting one another for the title. In the early sixties, Patterson cast himself as the Good Negro—an approachable yet strangely fearful man, a deferential champion of civil rights, integration, and Christian decency. The N.A.A.C.P. literally endorsed Patterson, as if he were running for Congress. Liston, a veteran of Missouri State Penitentiary before he came to the prize ring, accepted the role of the Bad Negro as his lot after he discovered that he would not be permitted any other. For most sportswriters, Liston was monstrous, indomitable, inexplicable, a Bigger Thomas, a Caliban beyond their reckoning.

As Cassius Clay, Ali craved their champion’s title but not their designated masks. “I had to prove you could be a new kind of black man,” Ali told me. “I had to show that to the world.”

As we watched and spoke, Ali was taken with the subject of himself, but sometimes his heavy lids would blink a few times and then stay shut and he would sleep, mid-conversation, for five minutes or so. He used to do that occasionally when he was young. Now he did it a lot more often. Sometimes the present world, the life going on all around—the awards dinners, the standing ovations, the visits to the King of Morocco or to the aldermen of Chicago—sometimes it just bored him. He thought about death all the time now, he said. “Do good deeds. Visit hospitals. Judgment Day coming. Wake up and it’s Judgment Day.” As a devout Muslim, Ali prayed five times a day, always with death in mind. “Thinking about after. Thinking about Paradise.”

But now he focussed on another sort of paradise. The Liston fight began. In black-and-white, Cassius Clay came bounding out of his corner and right away started circling the square, dancing, moving around and around the ring, moving in and out, his head twitching from side to side, as if freeing himself from a neck crick early in the morning, easy and fluid—and then Liston, a great bull whose shoulders seemed to cut off access to half the ring, lunged with a left jab. Liston missed by two feet. At that moment, Clay hinted not only at what was to come that night in Miami Beach but at what he was about to introduce to boxing and to sports in general—the marriage of mass and velocity. A big man no longer had to lumber along and slug: he could punch like a heavyweight and move like Ray Robinson.

“It’s sweet, isn’t it?” Ali smiled. With great effort, he smiled. Parkinson’s is a disease of the nervous system which stiffens the muscles and freezes the face into a stolid mask. Motor control degenerates. Speech degenerates. Some people hallucinate or suffer nightmares. As the disease progresses, even swallowing can become a terrible trial. Parkinson’s comes on the victim erratically. Ali still walked well. He was still powerful in the arms and across the chest; it was obvious, just from shaking his hand, that he still possessed a knockout punch. For him the special torture was speech and expression, as if the disease had intentionally struck first at what had once pleased him—and had pleased (or annoyed) the world—most. He hated the effort that speech now cost him. (“Sometimes you won’t understand me,” he said when we first met. “But that’s O.K. I’ll say it again.”)

Ali was smiling now as his younger self, Cassius Clay, flicked a nasty left jab into Liston’s brow.

“You watchin’ this?” he said. “So-o-o fast! So-o-o pretty!”

No matter how ruinous boxing is to boxers, there’s no doubt that part of Ali’s appeal derived from boxing, from going into a ring, stripped to the waist, a beautiful man, alone, in combat. It is perfectly plausible that as a basketball player or even as a swaddled halfback he would have been no less famous and quicksilver. But the boxer represents a more immediate form of dynamism, even supermasculinity, no matter how retrograde. For all his verbal gifts, Ali was first a supreme physical performer and sexual presence. “Ain’t I pretty?” he would ask over and over again, and, of course, he was. If he’d had the face of Sonny Liston, he would have lost much of his appeal.

Even as a schoolkid, Clay had a sense of glamour and performance. At Central High School, in Louisville, he paraded up and down the hallways shadowboxing and crying out his candidacy for the heavyweight crown—all in a style so over the top that he undercut the arrogance with laughter. He was probably our first rapper and our best. At the 1960 Summer Olympics, in Rome, when he was just eighteen, he wandered through the Olympic Village meeting people from all over the world and charming them with predictions about his great future. Clay was so much at ease that he became known as the Mayor of the Olympic Village. His experience in the ring in Rome was no less blissful. As a light heavyweight, he marched easily through his first three bouts, and then, in the finals, against a stubby coffeehouse manager from Poland named Zbigniew Pietrzykowski, he came back from a clumsy first round to win a unanimous decision and the gold medal. By the end of the bout, the Pole was bleeding all over Clay’s white satin shorts.

In Rome, Clay had fulfilled his mission, but he had done it in a style that offended the sensibilities of some of the older writers. Big men were supposed to fight like Joe Louis and Rocky Marciano: they were supposed to wade in and flatten their opponent. A. J. Liebling wrote in The New Yorker that Clay, though amusing to watch, lacked the requisite menace of a true big man. Liebling was not offended by Clay’s poetic pretensions: he was quick to remind his readers of Bob Gregson, the Lancashire Giant, who used to write such fistic couplets as “The British lads that’s here / Quite strangers are to fear.” It was Clay’s boxing manner that left Liebling in doubt. “I had watched Clay’s performance in Rome and had considered it attractive but not probative,” he wrote. “Clay had a skittering style, like a pebble scaled over water. He was good to watch, but he seemed to make only glancing contact. . . . A boxer who uses his legs as much as Clay used his in Rome risks deceleration in a longer bout.”

Whatever Liebling’s reservations, Clay was awarded his medal, with the word “pugilato” emblazoned across it. “I can still see him strutting around the Olympic Village with his gold medal on,” the late Wilma Rudolph, a great Olympic sprinter, once said. “He slept with it. He went to the cafeteria with it. He never took it off. No one else cherished it the way he did.”

After the awards ceremonies, a reporter from the Soviet Union asked Clay, in essence, how it felt to win glory for a country that did not give him the right to eat at Woolworth’s in Louisville.

“Tell your readers we’ve got qualified people working on that problem, and I’m not worried about the outcome,” Clay said. “To me, the U.S.A. is still the best country in the world, counting yours. It may be hard to get something to eat sometimes, but anyhow I ain’t fighting alligators and living in a mud hut.” That remark was printed in dozens of American papers as evidence of Clay’s good citizenship, his allegiance to the model fighters (and black men) who had come before him. Clay, it appeared, was ready to submit.

Boxing has never been a sport of the middle class. It is a game for the poor, the lottery player, the all-or-nothing-at-all young men who risk their health for the infinitesimally small chance of riches and glory. All Clay’s most prominent opponents—Liston, Patterson, Joe Frazier, George Foreman—were born poor, and more often than not into large families, often with fathers who were either out of work or out of sight. As boys, they were part of what sociologists and headline writers would later call the underclass. Cassius Clay, though, was a child of the black middle class—“but black middle class, black Southern middle class, which is not white middle class at all,” says Toni Morrison, who, as a young editor, worked on Ali’s autobiography. True enough, but still Clay was born to better circumstances than his eventual rivals. One of the less entertaining components of the Ali act was the way he tried to “out-black” someone like Frazier, calling him an Uncle Tom, an “honorary white,” when in fact Frazier had grown up dirt poor in South Carolina. If Ali was joking, Frazier never found it funny.

Clay’s mother, Odessa, was a sweet, light-skinned woman who took her sons to church every Sunday and kept after them to keep clean, to work hard, to respect their elders. Cassius Clay, Sr., who earned his livelihood as a sign painter, was a braggart, a charmer, a performer, a man full of fantastic tales and hundred-proof blather. To all who would listen, including reporters who trooped off to Louisville in later years, the senior Clay talked of having been an Arabian sheikh and a Hindu noble. Like Ralph Kramden, Jackie Gleason’s bus driver with dreams, the senior Clay talked up his schemes for the big hit, the marketing of this idea or that gadget which would vault the Clays, once and for all, out of Louisville and into some suburban nirvana. Cassius, Sr., always worked, but he had a weakness for the bottle, and when he drank he often became violent. The Louisville police records show that he was arrested four times for reckless driving, twice for disorderly conduct, and twice for assault and battery, and that on three occasions Odessa called the police complaining that her husband was beating her. “I like a few drinks now and then,” the senior Clay said. He often spent his nights moving from one bar to the next, picking up women whenever possible. (Many years later, Odessa finally grew so tired of her husband’s womanizing that she insisted on a period of separation.) John (Junior Pal) Powell, who owned a liquor store in the West End, once told a reporter for Sports Illustrated about a night when the old man came stumbling into his apartment, his shirt covered with blood. Some woman had stabbed him in the chest. When Powell offered to take him to the hospital, Clay refused, saying, “Hey, Junior Pal, the best thing you can do for me is do what the cowboys do. You know, give me a little drink and pour a little bit on my chest, and I’ll be all right.”

At an early age, Cassius Clay appears to have learned how to block these chaotic incidents from his mind. He would joke about his father’s having an eye for women—“My daddy is a playboy. He’s always wearing white shoes and pink pants and blue shirts and he says he’ll never get old”—but he would not let the discussion go much deeper. “It always seemed to me that Ali suffered a great psychological wound when he was a kid because of his father and that as a result he really shut down,” one of Ali’s closest friends said. “In many ways, as brilliant and charming as he is, Muhammad is an arrested adolescent. There is a lot of pain there. And though he’s always tried to put it behind him, shove it out of his mind, a lot of that pain comes from his father—the drinking, the occasional violence, the harangues.”

Cassius’s father did work hard to earn a living for his family, and there was a time in Louisville when his signs were everywhere. But the senior Clay was a resentful artisan. His greatest frustration was that he could not earn his living painting murals and canvases. He was not exceptionally talented—his landscapes were garish, his religious paintings just a step above kitsch—but then he had not had any training. He had quit school in the ninth grade, a circumstance he blamed, with good reason, on the limited opportunities for blacks. He often told his children that the white man had kept him down, had prevented him from being a real artist, from expressing himself. He was never subtle about his distrust of whites. And, though he would one day accuse the Nation of Islam of “brainwashing” and fleecing his two sons, Cassius and Rudy, he often went on at the dinner table and in the bars about the need for black self-determination. He deeply admired Marcus Garvey, the leading black nationalist after the First World War and one of the ideological forebears of Elijah Muhammad. He was never a member of a Garvey organization, but, like many blacks in the twenties, he admired Garvey’s calls for racial pride and black self-sufficiency, if not, perhaps, the idea of a return to Africa.

Like any black child of his generation, Cassius Clay learned quickly that if he strayed outside his neighborhood—into the white neighborhood of Portland, say—he would hear the calls of “Nigger!” and “Nigger go home!” Downtown, blacks were limited to the stores on Walnut Street between Fifth and Tenth Streets. Hotels were segregated. Schools were de-facto segregated, though there were slight signs of mixing even before Brown v. Board of Education. There were “white stores” and “Negro stores,” “white parks” and “Negro parks.” “That was just the way we lived,” said Beverly Edwards, one of Cassius’s schoolmates. “Kentucky is known as the Gateway to the South, but we weren’t too much different than the Deep South as far as race was concerned.” When Clay’s father told him all about the case of young Emmett Till, who had been beaten, mutilated, shot in the head, and thrown into the Tallahatchie River in the summer of 1955 by a pair of white men, Clay saw himself as Till, who was just a year older than he was. The killing helped reinforce in him the sense that he, a black boy from Louisville, was going out into a world that would inevitably deny him, rebuff him, even hate him. Cassius was no student—he graduated thanks only to the mercy of his high-school principal, Atwood Wilson—and so he sought a means of escape in the ring. “I started boxing because I thought this was the fastest way for a black person to make it in this country,” he would say years later.

Even before Clay went off to Rome, he had become fascinated by the Nation of Islam, better known as the Black Muslims. According to one biographer, Thomas Hauser, Cassius first heard about the group in 1959, when he travelled to Chicago for a Golden Gloves tournament. Chicago was the home base for the Nation and its leader, Elijah Muhammad, and Clay ran into Muslims on the South Side. His aunt remembers his coming home to Louisville with a record album of Muhammad’s sermons. Then, the next spring, before leaving for the Olympics, Clay read a copy of the Nation’s official newspaper, Muhammad Speaks. He was clearly taken with what he was reading and hearing in the Muslim rhetoric of pride and separatism. “The Muslims were practically unknown in Louisville in those days,” Clay’s high-school classmate Lamont Johnson told me. “They had a little outfit, a temple, run by a black guy with white spots on his skin, but no one paid it any mind. No one had heard about their bean pies, the way they lived, what they thought. It wasn’t even big enough to be scary in 1959.”

Clay stunned his English teacher at Central High when he told her he wanted to write his term paper on the Black Muslims. She refused to let him do it. He never let on that his interest in the group was more than a schoolboy’s passing curiosity, but something had resonated in his mind—something about the discipline and the bearing of the Muslims, their sense of hierarchy, manhood, and self-respect, the way they refused to smoke or drink or carouse, their racial pride.

After coming back from Rome, Clay attended meetings, in various cities, of the N.A.A.C.P., of core—the Congress of Racial Equality—and of the Nation of Islam. Other athletes, like Curt Flood and Bill White, of the St. Louis Cardinals, had stopped in to hear Muslim preachers, too, but had left after listening for a few minutes to the rhetoric about “blue-eyed devils.” Clay, however, was impressed by the Muslims in a way he was not by any other group or church. “The most concrete thing I found in churches was segregation,” he said years later to the journalist Jack Olsen. “Well, now I have learned to accept my own and be myself. I know we are original man and that we are the greatest people on the planet Earth and our women the queens thereof.”

Through 1961 and 1962, Clay kept his interest in the Nation of Islam quiet (he was well aware that to announce his new loyalty would put a title fight at risk), but he was quite publicly gaining strength both as a fighter and as a performer. He beat a succession of heavyweights—Alonzo Johnson, Alex Miteff, Willie Besmanoff, Sonny Banks, George Logan, Billy Daniels, Alejandro Lavorante—and even at the most perilous moment, when he got too careless in the first round, too glib, and Banks knocked him down, he showed a new ability to take a punch, and he recovered to win easily in four. Afterward, Harry Wiley, Banks’s cornerman and a legendary New York boxing fixture, described the phenomenon of fighting Clay: “Things just went sour gradually all at once. He’ll pick you and peck you, peck you and pick you, until you don’t know where you are.”

By then, Clay may have been the most self-aware twenty-year-old in the country. Like the most intelligent of comedians or actors or politicians, he was in complete command of even the most outrageous performances. “Where do you think I’d be next week if I didn’t know how to shout and holler and make the public take notice?” he said. “I’d be poor and I’d probably be down in my home town, washing windows or running an elevator and saying ‘yassuh’ and ‘nawsuh’ and knowing my place.”

In his sixth fight as a professional, in April, 1961, Clay took on Lamar Clark, a tough heavyweight with forty-five knockouts in a row. Clay made a prediction, the first of many: Clark would be gone in two. And so he was. Two rounds into the fight, Clay had broken Clark’s nose and dropped him to the canvas twice, and the referee ended it there. “The more confident he became, the more his natural ebullience took over,” one of his cornermen, Ferdie Pacheco, told me. “Everything was such fun to him. Maybe it wouldn’t have been so much fun if someone had knocked him lopsided, but no one did. No one shut him up. And so he just kept predicting and winning, predicting and winning. It was like ‘Candide’—he didn’t think anything bad could happen in this best of all possible worlds.”

Clay’s next fight was in Las Vegas against a gigantic Hawaiian, Duke Sabedong. One of Clay’s prefight promotional duties was to appear on a local radio show with Gorgeous George, the preëminent professional wrestler of the time. Gorgeous George (known to his mother as George Raymond Wagner) was the first wrestler of the television age to exploit the possibilities of theatrical narcissism and a flexible sexual identity—Liberace in tights. His hair was long and blond, and when he entered the ring he wore curlers. In his corner, he would release the curlers and let one of his minions brush out the golden hair to his shoulders. He wore a robe of silver lamé, and his fingernails were trimmed and polished. One lackey sprayed the ring mat with insecticide, another sprayed Gorgeous George with eau de cologne.

At the radio interview, Clay was not exactly silent. He was already known by various nicknames in the press (Gaseous Cassius, the Louisville Lip, Cash the Brash, Mighty Mouth, Claptrap Clay, etc.), and he was quick to predict an easy win over Duke Sabedong. But compared with Gorgeous George he was tongue-tied. “I’ll kill him!” Gorgeous ranted. “I’ll tear his arm off! If this bum beats me, I’ll crawl across the ring and cut my hair off, but it’s not gonna happen, because I’m the greatest wrestler in the world!”

Gorgeous George was already forty-six—he had been retailing this shtick for years—but Clay was impressed, the more so when he saw Gorgeous George perform. Every seat in the arena was filled and nearly every fan was screaming for George’s gilded scalp. But the point was, the arena was filled. “A lot of people will pay to see someone shut your mouth,” George told Clay after that bout. “So keep on bragging, keep on sassing, and always be outrageous.”

In November of 1962, Clay fought Archie Moore, who was by then forty-seven (more or less) and was the veteran of two hundred fights. “I wasn’t a fool. I knew how old I was, and I knew Clay from training him for a while,” Moore told me decades later. “But I felt pretty good about Clay, and I thought if I could bear down I could beat him. I had to outbox him or wait him out. He was so young, and you can never tell what a young man can do in boxing.” The truth was, Moore badly needed the purse. His only chance was that Clay’s inexperience would yield an opening for a right hand and a knockout. That was unlikely, according to the oddsmakers. Clay was a three-to-one favorite, and his prediction was for a quick night: “When you come to the fight, don’t block the aisle and don’t block the door. You will all go home after Round Four.”

Clay and Moore sold out the arena in Los Angeles, not least because they kept up the verbal sparring at every venue possible, and especially on television. The two fighters even staged a half-hour mock debate.

“The only way I’ll fall in four, Cassius, is by tripping over your prostrate form,” Moore said.

“If I lose,” said Clay, “I’m going to crawl across the ring and kiss your feet. Then I’ll leave the country.” “Don’t humiliate yourself,” the old man replied. “Our country’s depending on its youth. Really, I don’t see how you can stand yourself. I am a speaker, not a rabble-rouser. I’m a conversationalist, you’re a shouter.”

Moore, a Liebling favorite, played the avuncular elder to the boorish wanna-be. With his Edwardian diction, Moore looked upon Clay as a duke would upon the unwashed. After their exchange, he reflected on the upstart with a certain professorial remove. “I view this young man with mixed emotions,” he said. “Sometimes he sounds humorous, but sometimes he sounds like Ezra Pound’s poetry. He’s like a man who can write beautifully but doesn’t know how to punctuate. He has this twentieth-century exuberance, but there’s bitterness in him somewhere. . . . He is certainly coming along at a time when a new face is needed on the boxing scene, on the fistic horizon. But in his anxiousness to be this person he may be overplaying his hand by belittling people. . . . I don’t care what Cassius says. He can’t make me mad. All I want to do is knock him out.”

Once the two fighters were in the arena, stripped of their robes and their promotional poses, it was impossible to ignore the physical difference. Clay was sleek as an otter, and not even at his peak of strength. He would fill out later. Moore was middle-aged. His hair was going gray. Fat jiggled on his arms. He kept his trunks pulled up around his nipples.

In the first round, Clay conducted a survey. Moore had a reputation for speed (now gone) and as a sneak, the master of the quick, unseen punch. He was known as the Mongoose. But Clay, as he flashed his jabs into Moore’s face, seemed to convince himself that there would be no answer coming. Each jab that Clay bounced off Moore’s scalp assured the younger man of the cruelty of age—a soothing discovery to him, if not to Moore.

In the second, Moore actually caught Clay with a right hand. It shot up out of a crowd of tangled arms and gave Clay a start, but there was nothing much to it. In the third, Moore was already so exhausted from trying to keep up that his arms began to sink. His inclination to send any damage Clay’s way was down to nothing. Moore crouched, lower and lower, as if to meld with the canvas, but Clay’s reach was long, and he leaned over to drill one left hook after another into Moore’s bald spot. Years later, Moore would say that those punches, in their accumulation, made him dizzy: “They stirred the mind.”

Clay was doing whatever he wanted. Every punch landed—the jabs, the hooks, the quick overhand rights—and Moore was barely hanging on, squatting lower and lower. Mid-way through the third, Clay hit Moore square on the chin. Moore wobbled. Then he took a few running steps backward to the rope, found it, and hung on. Clay refused to follow up, more for aesthetic reasons, it seemed, than for lack of intent. He had predicted a fourth-round knockout and wanted to maintain his pure vision of the fight.

Clay came out flat-footed in the fourth, the better to leverage his punches, and, after a few preliminary jabs to warm up his shoulders, he started looking for the knockout. Moore bent at the waist again, as if in prayer, but he could not bow low enough. He took a few wild swings to preserve his name, and Clay jabbed back, scolding him for the delay. Clay circled and circled, then suddenly jumped in with an uppercut that straightened Moore out of his crouch, and then a few more punches, all sharp and straight, like clean hammer raps on a nail, put him down. Clay stood over the prostrate lump to take his bow, shuffled his feet in a flash, and then retreated, reluctantly, to the neutral corner. He disdained this obligatory retreat; it meant leaving center stage.

Moore, meanwhile, roused himself and rolled onto his left side, an old man waking from a fitful sleep. Then he pridefully lifted himself to his feet just before “ten.” With a look of annoyance (he’d thought it was over), Clay met Moore again in the center of the ring and started punching. Moore took one wild swing, as if to acquit himself of any lingering charges of resignation, and then slowly melted back to the floor as Clay hit him on top of the head. The time had come, and Moore knew it. He stayed on his backside.

With the fight over, Clay hugged Moore sweetly, the way one would embrace a grandfather.

Later, Moore responded with an endorsement. “He’s definitely ready for Liston,” he told the reporters gathered around him. “Sonny would be difficult for him and I would hesitate to say he could beat the champ, but I’ll guarantee he would furnish him with an exceedingly interesting evening.”

In 1963, when Clay signed to fight Sonny Liston for the title the following February, print was still the supreme medium of communication and hype, and the most powerful men in sports were the columnists. To promote the fight, to create an image of himself in the public mind, Clay would have to work through them. As a filter, the press was monochromatic. Nearly all the columnists were white, middle-aged, and raised on Joe Louis as the beau ideal of proper black comportment. Despite Liston’s multiple arrests, two-year prison term, and baleful disdain, they were inclined to like Clay even less than Liston. At least, they thought, Liston could fight. Clay was a talker, and they resented that. Language was their property, not the performer’s. Jim Murray, of the Los Angeles Times, remarked of Clay that “his public utterances have all the modesty of a German ultimatum to Poland but his public performances run more to Mussolini’s Navy.” According to one poll, ninety-three per cent of the writers accredited to cover the fight predicted that Liston would win. What the poll did not register was the firmness of the predictions. Arthur Daley, the New York Times columnist, seemed to object morally to the fight, as if the bout were a terrible crime against children and puppies: “The loud mouth from Louisville is likely to have a lot of vainglorious boasts jammed down his throat by a ham-like fist belonging to Sonny Liston.”

Jimmy Cannon, late of the Post and with the Journal-American since 1959, was the king of the columnists. Cannon was the first thousand-dollar-a-week man, Hemingway’s favorite, Joe DiMaggio’s buddy, and Joe Louis’s iconographer. Red Smith, who wrote for the Herald Tribune, employed an elegant restraint in his prose, which put him ahead of the game with more high-minded readers, but Cannon was the popular favorite: a world-weary voice of the city. Cannon was king, and Cannon had no truck with Cassius Clay.

One afternoon shortly before the fight, Cannon was sitting with George Plimpton at the Fifth Street Gym, in Miami Beach, watching Clay spar. Clay glided around the ring, a feather in the slipstream, and every so often he popped a jab into his sparring partner’s face. As he recalled in his book “Shadow Box,” Plimpton was completely taken with Clay’s movement, his ease, but Cannon couldn’t bear to watch.

“Look at that!” Cannon said. “I mean, that’s terrible. He can’t get away with that. Not possibly.” It was just unthinkable that Clay could beat Liston by running, keeping his hands at his hips, and defending himself simply by leaning away.

“Perhaps his speed will make up for it,” Plimpton put in hopefully.

“He’s the fifth Beatle,” Cannon said. “Except that’s not right. The Beatles have no hokum to them.”

“It’s a good name,” Plimpton said. “The fifth Beatle.”

“Not accurate,” Cannon said. “He’s all pretense and gas, that fellow. . . . No honesty.”

Clay offended Cannon’s sense of rightness the way flying machines offended his father’s generation. It threw his universe out of kilter. “In a way, Clay is a freak,” he wrote before the fight. “He is a bantamweight who weighs more than two hundred pounds.”

Cannon’s objections went beyond the ring. His hero was Joe Louis, and for Joe Louis he composed the immortal line that he was a “credit to his race—the human race.” He admired Louis’s “barbaric majesty,” his quiet in suffering, his silent satisfaction in victory. And when Louis finally went on too long and, way past his peak, fought Rocky Marciano, he eulogized the broken-down old fighter as the metaphysical poets would a slain mistress: “The heart, beating inside the body like a fierce bird, blinded and caged, seemed incapable of moving the cold blood through the arteries of Joe Louis’ rebellious body. His thirty-seven years were a disease which paralyzed him.”

Cannon was born in 1910, in what he called “the unfreaky part of Greenwich Village.” His father was a minor, if kindly, servant of Tammany Hall. Cannon dropped out of school after the ninth grade, caught on as a copyboy at the News, and never left the newspaper business. As a young reporter, he caught the eye of Damon Runyon when he wrote dispatches on the Lindbergh kidnapping trial for the International News Service.

“The best way to be a bum and make a living is to be a sportswriter,” Runyon told Cannon, and he helped him get a job at a Hearst paper, the New York American, in 1936. Like his heroes Runyon and the Broadway columnist Mark Hellinger, Cannon gravitated to the world of the “delicatessen nobility,” to the bookmakers and touts, the horseplayers and talent agents, who hung out at Toots Shor’s and Lindy’s, the Stork Club and El Morocco. When Cannon went off to Europe to write battle dispatches for Stars & Stripes, he developed what would become his signature style: florid, sentimental prose with an underpinning of hard-bitten wisdom, an urban style that he had picked up in candy stores and night clubs and from Runyon, Ben Hecht, and Westbrook Pegler. Cannon would begin some columns by putting the reader inside the skull and uniform of a ballplayer (“You’re Eddie Stanky. . . . You ran slower than the other guy”), and elsewhere, in that voice of Lindy’s at three in the morning, he would dispense wisdom on the subject he seemed to know the least about—women: “Any man is in difficulty if he falls in love with a woman he can’t knock down with the first punch,” or, “You could tell when a broad starts in managing a fighter. What makes a dumb broad smart all of a sudden? They don’t even let broads in a joint like Yale. But they’re all wised up once a fighter starts making a few.”

The wised-up one-liners and the world-weary sentiment belonged to a particular time and place, and as Cannon aged he gruffly resisted new trends in sportswriting and athletic behavior. In the press box, he encountered a new generation of beat writers and columnists—men like Maury Allen and Leonard Shecter, of the Post. He didn’t much like the sound of them. Cannon called the younger men Chipmunks, because they were always chattering away. He hated their impudence, their irreverence, their striving to get outside the game and into the heads of the people they covered. Cannon had always said that his intention as a sportswriter was to bring the “world in over the bleacher wall,” but he failed to see that this generation was trying to do much the same thing. He couldn’t bear their lack of respect for the old verities. “They go up and challenge guys with rude questions,” Cannon once said of the Chipmunks. “They think they’re very big if they walk up to an athlete and insult him with a question. They regard this as a sort of bravery.”

Part of Cannon’s anxiety was sheer competitiveness. There were seven newspapers in New York in those days, and there was terrific competition to stay on top, to be original, to get a scoop, an extra detail. But the younger writers—and even some contemporaries, like Milton Gross, of the Post—knew they were in competition now not so much with one another as with the growing power of television. Unlike Cannon, who was almost entirely self-educated, the younger men (and they were still all men) had gone to college in the age of Freud. They became interested in the psychology of an athlete (“The Hidden Fears of Kenny Sears” was one of Milton Gross’s longer pieces). In time, this, too, would no longer seem especially voguish—soon just about every schnook with a microphone would be asking the day’s goat, “What were you thinking when you missed that ball?”—but for the moment the Chipmunks were the coming wave and Cannon’s purple sentences, once so pleasurable, were beginning to feel less vibrant, a little antiquated.

The new generation—men like Pete Hamill and Jack Newfield, Jerry Izenberg and Gay Talese—all admired Cannon’s immediacy, but Cannon begrudged them their new outlook, their educations, their youth. In the late fifties, Talese wrote many elegant features for the Times and then, in the sixties, even more impressively, a series of profiles for Esquire, on Patterson, Louis, DiMaggio, Frank Sinatra, and the theatre director Joshua Logan. When Talese left the paper, in 1965, he had one heir in place, a reporter in his mid-twenties named Robert Lipsyte. It was left to Lipsyte to interpret this new phenomenon Cassius Clay to the élite, to the readers of the Times.

Like Cannon, Lipsyte grew up in New York, but he was a middle-class Jew from the Rego Park neighborhood of Queens, with a Columbia education. Lipsyte made the Times reporting staff at twenty-one with a display of hustle and ingenuity: one day the hunting-and-fishing columnist failed to send in a column from Cuba, so Lipsyte sat down and, on deadline, knocked out a strange and funny column on how fish and birds were striking back at anglers and hunters. Lipsyte wrote about high-school basketball players like Connie Hawkins and Roger Brown. He helped cover the 1962 Mets with Louis Effrat, a Times man who had lost the Dodgers beat when they moved out of Brooklyn. Effrat’s admiration for his younger colleague was, to say the least, grudging: “Kid, they say in New York you can really write, but you don’t know what the fuck you’re writing about.” If there was one subject that Lipsyte made it a point to learn about, it was race. In 1963, he met Dick Gregory, one of the best comics in the country and a constant presence in the civil-rights movement. The two men became close friends, and eventually Lipsyte helped Gregory write “Nigger,” his autobiography. Even as a sports reporter, Lipsyte contrived ways to write about race. He wrote about Chicago’s Blackstone Rangers gang, and he got to know Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad. He covered rallies at which African-Americans expressed their outrage against a country that would celebrate blacks only when they carried a football or boxed in a twenty-foot ring.

In the winter of 1963-64, the Times’ regular boxing writer, Joe Nichols, declared that the Liston-Clay fight was a dog and that he was going off to spend the season covering racing at Hialeah. The assignment went to Lipsyte.

Unlike Cannon and the other village elders of the sports pages, Lipsyte found himself entranced with Clay. Here was this entertaining, beautiful, skilled young man who could fill your notebook in fifteen minutes. “Clay was unique, but it wasn’t as if he were some sort of creature from outer space for me,” Lipsyte said. “For Jimmy Cannon, he was, pardon the expression, an uppity nigger, and he could never handle that. The blacks he liked were the blacks of the thirties and the forties. They knew their place. Joe Louis called Jimmy Cannon ‘Mr. Cannon’ for a long time. He was a humble kid. Now here comes Cassius Clay popping off and abrasive and loud, and it was a jolt for a lot of sportswriters, like Cannon. That was a transition period. What Clay did was make guys stand up and decide which side of the fence they were on. Clay upset the natural order of things at two levels. The idea was that he was a loud braggart and brought disrespect to this noble sport. Or so the Cannon people said. Never mind that Rocky Marciano was a slob who would show up at events in a T-shirt so that the locals would buy him good clothes. They said that Clay ‘lacked dignity.’ Clay combined Little Richard and Gorgeous George. He was not the sort of sweet dumb pet that writers were accustomed to. Clay also did not need the sportswriters as a prism to find his way. He transcended the sports press. Jimmy Cannon, Red Smith—so many of them—were appalled. They didn’t see the fun in it. And, above all, it was fun.”

A week before the Liston fight, Clay stretched out on a rubbing table at the Fifth Street Gym and told Lipsyte and the rest of the assembled reporters, “I’m making money, the popcorn man making money, and the beer man, and you got something to write about.”

Clay’s uncanny sense of self-promotion didn’t stop at his daily monologues. The next day, Lipsyte heard that the Beatles would be dropping by the Fifth Street Gym. The Beatles were in Miami to do “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Liston had actually gone to their studio performance and was not much impressed. As the Beatles ripped through their latest single, the champion turned sourly to the public-relations man Harold Conrad and said, “My dog plays drums better than that kid with the big nose.” Conrad figured that Clay, and the younger reporters, would understand better.

Lipsyte was a card-carrying member of the rock-and-roll generation, and he saw that, for all its phonyness, a meeting between the Beatles and Clay was a meeting of the new, two acts that would surely mark the sixties. The older columnists passed, but Lipsyte saw a story.

The Beatles arrived. They were still in their mop-top phase, but they were already quite aware of their own pop status and appeal. Clay was not in evidence, and Ringo Starr was angry. “Where the fuck’s Clay?” he said.

To kill a few minutes, Ringo began introducing the members of the band to Lipsyte and a few other reporters, though he introduced George Harrison as Paul and Lennon as Harrison, and finally Lennon lost patience.

“Let’s get the fuck out of here,” he said. But two Florida state troopers blocked the door and somehow kept them in the gym just long enough for Clay to show up.

“Hello, there, Beatles,” Cassius Clay said. “We oughta do some road shows together. We’ll get rich.” The photographers lined up the Beatles in the ring, and Clay faked a punch to knock them all to the canvas: the domino punch.

Now the future of music and the future of sports began talking about the money they were making and the money they were going to make. “You’re not as stupid as you look,” Clay concluded.

“No,” Lennon said, “but you are.” Clay checked to make sure Lennon was smiling, and he was. The younger writers, like Lipsyte, really did see Clay as a fifth Beatle. This was just a few months after the Kennedy assassination, and the country was already in the midst of a social and political earthquake; the fighter from Louisville and this band from Liverpool were part of it, leading it, whether they knew it yet or not.

For most of the older columnists, however, this P.R.-inspired scene at the Fifth Street Gym was just more of all that was going wrong in the world—more noise, more disrespect, more impudence from young men they could not hope to comprehend. “Clay is part of the Beatle movement,” Jimmy Cannon wrote a few years later. “He fits in with the famous singers no one can hear and the punks riding motorcycles with iron crosses pinned to their leather jackets and Batman and the boys with their long dirty hair and the girls with the unwashed look and the college kids dancing naked at secret proms held in apartments and the revolt of students who get a check from Dad every first of the month and the painters who copy the labels off soup cans and the surf bums who refuse to work and the whole pampered style-making cult of the bored young.”

At the Fifth Street Gym, Clay was also setting a physical and psychological trap for the fighter he called “the big ugly bear.” While Liston prepared for the fight by eating hot dogs and hanging out with a couple of prostitutes on Collins Avenue, Clay trained hard every day. Then, afterward, in his sessions with reporters, he described how he would spend the first five rounds circling Liston, tiring him out, and then tear him apart with hooks and uppercuts until finally the champion would drop to all fours in submission. “I’m gonna put that ugly bear on the floor, and after the fight I’m gonna build myself a pretty home and use him as a bear-skin rug. Liston even smells like a bear. I’m gonna give him to the local zoo after I whup him. People think I’m joking. I’m not joking. I’m serious. This will be the easiest fight of my life.” He told the visiting reporters that now was their chance to “jump on the bandwagon.” He was taking names, he said, keeping track of all the naysayers, and when he won “I’m going to have a little ceremony and some eating is going on, eating of words.”

In honor of the fight, Clay composed what was surely his best poem. Over the years, Clay would farm out some of his poetical work. “We all wrote lines here and there,” Dundee, the trainer, said. But this one was all Clay. Ostensibly, it was a prophetic vision of the eighth round, and no poem, before or after, could beat it for narrative drive, scansion, and wit. It was his “Song of Myself”:

Clay comes out to meet Liston

And Liston starts to retreat.

If Liston goes back any further

He’ll end up in a ringside seat.

Clay swings with a left,

Clay swings with a right,

Look at young CassiusCarry the fight.

Liston keeps backing

But there’s not enough room.

It’s a matter of time.

There Clay lowers the boom.

Now Clay swings with a right,

What a beautiful swing,

And the punch raises the bear

Clear out of the ring.

Liston is still rising

And the ref wears a frown,

For he can’t start counting

Till Sonny comes down.

Now Liston disappears from view.

The crowd is getting frantic,

But our radar stations have picked him up,

He’s somewhere over the Atlantic.

Who would have thought

When they came to the fight That they’d witness the launching

Of a human satellite?

Yes, the crowd did not dream

When they laid down their money

That they would see

A total eclipse of the Sonny!

Nearly all the writers regarded Clay’s bombast, in prose and verse, as the ravings of a lunatic. But not only did Clay have a sense of how to fill a reporter’s notebook and, thus, a promoter’s arena; he had a sense of self. The truth (and it was a truth he shared with almost no one) was that he knew that, for all his ability, for all his speed and cunning, he had never met a fighter like Sonny Liston. In Liston, Clay was up against a man who did not merely beat his opponents but hurt them, damaged them, shamed them in humiliatingly fast knockouts. Liston could put a man away with his jab; he was not much for dancing, but then neither was Joe Louis. When he hit a man in the solar plexus, the glove seemed lost up to the cuff; he was too powerful to grab and clinch; nothing hurt him. Clay was too smart, he had watched too many films, not to know that.

“That’s why I always knew that all of Clay’s bragging was a way to convince himself that he could do what he said he’d do,” Floyd Patterson told me many years later. “I never liked all his bragging. It took me a long time to understand who Clay was talking to. Clay was talking to Clay.”

Up in Michigan, more than thirty years later, Ali sat in his office on the farm. The office was on the second floor of a small house behind the main house, and it served as the headquarters of the company known as goat—the Greatest of All Time. Outside, geese glided along a pond. A few men were working in the fields. Someone was mowing the great lawn that rolled away from the house and up to the gates of the property. There were various fine cars around, including a Stutz Bearcat. There was a tennis court, a pool, and playground equipment sufficient for a small school in a well-taxed municipality. Ali is father to nine children: the oldest is Maryum, who is thirty, and the youngest is Asaad Ali, a seven-year-old boy, whom Muhammad and his fourth wife, Lonnie, adopted. “Muhammad finally found a playmate,” Lonnie told me. “He wasn’t around much for his other children, but now he gets to play with Asaad all the time.” The Alis loved living on the farm, but lately they had been looking for a buyer. When I was there, they talked to some people who wanted to buy the place and convert it into a wellness center. They had even tried to unload it on a television home-shopping network. Eventually, Lonnie said, the family will move back to Louisville, where they hope a Muhammad Ali center will be built. Ali’s parents have died, but his brother still works in Louisville.

Although Ali insists he spends most of his time these days “thinking about Paradise,” it’s not as if he’s put his past behind him. He earns his living making appearances and signing pictures, which are then sold at auction and to dealerships. Sometimes, when he is sleeping, Ali dreams about his old fights, especially the three wars in the seventies with Joe Frazier. When the documentary film about his triumph in Zaire, “When We Were Kings,” opened, in 1996, Ali watched the tape many times. In Los Angeles, when the film won an Academy Award for best documentary feature, Ali was called onstage and wordlessly accepted a standing ovation.

His greatest triumph in retirement came on the summer night in Atlanta when, to the surprise of nearly everyone watching, he suddenly appeared with a torch in his hands, ready to open the 1996 Summer Olympics. Ali stood with the heavy torch extended before him, and three billion people could see him shaking, both from the Parkinson’s and from the moment itself. But Ali carried it off. “Muhammad wouldn’t go to bed for hours and hours that night,” Lonnie said. “He was floating on air. He just sat in a chair back at the hotel holding the torch in his hands. It was like he’d won the heavy-weight title back a fourth time.”

Lonnie Ali is a handsome woman with a face full of freckles. She is fifteen years younger than her husband and grew up near the Clay family in Louisville’s West End. When Ali’s third marriage, to Veronica Porsche, was on its way out, he called her to come be with him. Eventually, Ali and Lonnie married. Lonnie is precisely what Ali needs. She is smart—a Vanderbilt graduate—she is calm and loving, and she does not treat Ali like her patient. Besides Ali’s closest friend, the photographer Howard Bingham, Lonnie is probably the one person in his life who has given more than she has taken. In Michigan, Lonnie runs the household and the farm, and when they are on the road, which is more than half the time, she keeps watch over Ali, making sure he has rested enough and taken his medicine. She knows his moods and habits, what he can do and what he can’t. She knows when he is suffering and when he is hiding behind his symptoms to zone out of another event that bores him.

When Lonnie came into the room where we were watching a tape of the Liston fight, Ali didn’t look up from the television. He merely reached out and rested his hand on the small of her back.

“Muhammad, you’ve got to sign a couple of pictures, O.K?” she said. She put a couple of eight-by-ten glossies in front of him. Cassius Clay was dancing around the ring, stopping only to needle a tattoo on the meat of Sonny Liston’s face.

“Ali, can you make that ‘To Mark’? M-A-R-K. And ‘To Jim.’ J-I-M. And later on you’ve got to sign some pictures and some boxing gloves.”

Ali made plenty of money in boxing, but he didn’t keep as much of it as he could have. There were alimonies, hangers-on, the I.R.S., good times, the Nation of Islam.

“I sign my name, we eat,” he said sheepishly.

The tape kept rolling. By the third round, Cassius Clay was in complete control of Sonny Liston. There were welts under both of Liston’s eyes. He had aged a decade in minutes. Ali loved it then, and he was loving it now. “People shouted every time Liston threw a punch,” he whispered. “They was waitin’. But now they can’t believe it. They thought Liston’d knock me into the crowd. Look at me!” Clay danced and jabbed. By the sixth round, Clay was a toreador filling a bull’s back with blades.

Now it was over. Ali smiled as he watched his younger self dancing around the ring, shouting “I’m the king of the world! King of the world!” and climbing the ring ropes and pointing down at all the sportswriters: “Eat your words! Eat your words!” The next day, Clay would announce that he was a member of the Nation of Islam. Within a few weeks, he would accept a new name. And within a couple of years he would become the most recognizable face on the planet.

A cleaning woman walked into the room, put aside her vacuum cleaner, and sat down to watch the tape with us. Cassius Clay was still shouting “King of the world!” “Ain’t I pretty?” Ali asked her.

“Oh, Ali,” she said. “You had a big mouth then.”

“I know,” he said, smiling. “But wasn’t I pretty? I was twenty . . . twenty what? Twenty-two. Now I’m fifty-four. Fifty-four.” He said nothing for a minute or so. Then he said, “Time flies. Flies. Flies. It flies away.”

Then, very slowly, Ali lifted his hand and fluttered his fingers like the wings of a bird. “It just flies away,” he said.♦