PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

THE ZAMBIAN “AFRONAUT” WHO WANTED TO JOIN THE SPACE RACE

Namwali Serpell | March 10, 2017 | THE NEW YORKER

At the height of the Cold War, a schoolteacher launched the Zambian Space Program with a dozen aspiring teen-age astronauts. Was he unfairly mocked?

My country was born on October 24, 1964. The former British protectorate of Northern Rhodesia, taking its new name from the great Zambezi River, would henceforth be known as Zambia. A week later, Time magazine published an article that focussed on the nation’s first President, Kenneth David Kaunda, a “teetotaling, guitar-strumming, nonsmoking Presbyterian preacher’s son and ex-schoolteacher,” who advocated for “positive neutrality” in the Cold War and for a “multiracial society” in Zambia. Another figure appeared in the article’s closing paragraph:

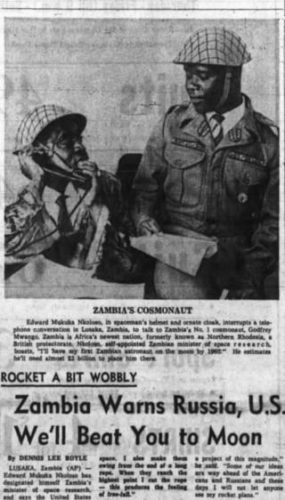

One noted Zambian failed to share in all the harmony. He is Edward Mukuka Nkoloso, a grade-school science teacher and the director of Zambia’s National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy, who claimed the goings-on interfered with his space program to beat the U.S. and the Soviet Union to the moon. Already Nkoloso is training twelve Zambian astronauts, including a curvaceous 16-year-old girl, by spinning them around a tree in an oil drum and teaching them to walk on their hands, “the only way humans can walk on the moon.”

Time’s whimsical footnote prompted a flurry of interest from foreign reporters. “We do not know whether to take the announcement of this news from Lusaka seriously, or whether to conclude that Zambia somehow has been victimized by a Madison Avenue type,” one confessed. Others wondered if it was “a semiserious space program” or “a useful publicity stunt.” Their interviews with Nkoloso did little to clarify whether his space program was serious, silly, or a sendup. “Some people think I’m crazy,” Nkoloso told a reporter for the Associated Press. “But I’ll be laughing the day I plant Zambia’s flag on the moon.”

Nkoloso wore a standard-issue combat helmet, a khaki military uniform, and a flowing cape—multicolored silk or heliotrope velvet, with an embroidered neck and festooned with medals. His astronauts sometimes wore green satin jackets with yellow trousers. (They were quick to explain that these were not space suits: “No, we are the Dynamite Rock Music Group when we are not space cadets.”) Godfrey Mwango, at twenty-one, had been tasked with the moon landing. Matha Mwamba, sixteen, was headed for Mars. Nkoloso’s dog, Cyclops, was to follow in the paw prints of Russian “muttnik” Laika. The other cadets carried a Zambian flag and a staff in the shape of “a crested eagle on a dinner plate atop a sawn-off broomstick.” Nkoloso said he had been inspired by his first airplane flight. When the pilot refused to stop the plane so that he could get out and walk on the clouds, Nkoloso made up his mind to enter the space race.

Newspapers also reported the large sums of money, ranging from twenty million to two billion dollars, that Nkoloso requested from Israel, Russia, the U.S., the United Arab Republic, and unesco. (One saw “piles of letters from foreign well-wishers containing plenty of advice—but no money beyond a 10-rupee note sent by a space-minded Indian schoolboy.”) Despite Nkoloso’s indifference as to which side of the Cold War would fund his space program, he insisted on keeping its details secret. “You cannot trust anyone in a project of this magnitude,” he said. “Some of our ideas are way ahead of the Americans and the Russians and these days I will not let anyone see my rocket plans.”

Yet Nkoloso welcomed reporters into his headquarters, which changed location according to his day job, and were cluttered with space-related volumes donated by the U.S. Embassy: a “Space Aids Mankind” calendar, and the Zambian Space Program Manifesto. “Our spacecraft, Cyclops I, will soar into deep abysmal space beyond the epicycles of the seventh heaven,” it proclaimed, before gesturing toward how much the space race was about race. “Our posterity, the Black scientists, will continue to explore the celestial infinity until we control the whole of outer space.” Nkoloso was also happy to demonstrate his D.I.Y. space technology and training. He rolled his cadets down a hill in a forty-gallon oil drum to simulate the weightless conditions of the moon. “I also make them swing from the end of a long rope,” he told a reporter. “When they reach the highest point, I cut the rope. This produces the feeling of freefall.” The mulolo (swinging) system, he hinted, was itself a potential means of space travel. “We have tied ropes to tall trees and then swung our astronauts slowly out into space.” Nkoloso had considered launching the shuttle with a mukwa (catapult) system that turned out to be “much too primitive,” and referred to “turbulent propulsion” as an area for future investigation.

As you may have guessed, the Zambian Space Program never got off the ground. “My spacemen thought they were film stars. They demanded payment,” Nkoloso told the A.P. in August, 1965. “Two of my best men went on a drinking spree a month ago and haven’t been seen since . . . Another of my astronauts has joined a local tribal song and dance group.” Even in the early days, Nkoloso had complained that “they won’t concentrate on space flight—there’s too much love making when they should be studying the moon.” Matha Mwamba eventually got pregnant and dropped out. The program suffered from a lack of funds, for which Nkoloso blamed “those imperialist neocolonialists” who were, he insisted, “scared of Zambia’s space knowledge.”

I first encountered Nkoloso in a work of art that tries to imagine a different outcome. My friend sent me a link to Frances Bodomo’s short film “Afronauts” (2014). In the film, set on the night of the Apollo 11 moon launch, “a group of exiles in the Zambian desert are rushing to launch their rocket first.” It is just one of several works of art inspired by the Zambian Space Program that have emerged over the last five years, as part of the recent resurgence of interest in black science and science fiction (the film “Hidden Figures,” Janelle Monáe’s music). In 2012, Cristina de Middel made a series of surreal photographic re-creations of Nkoloso’s space program. In the photos, models in raffia skirts and Afro-patterned space suits meander across a desert fitted with rusted machinery and impassive elephants. Projects like this present Nkoloso as an eccentric visionary—an early pioneer of Afrofuturism, a term Mark Dery coined in 1992 to describe the nexus of black art and technoculture. Dreamy and speculative, they are a little flexible with facts. (There are no deserts in Zambia.)

Because we live in a miraculous world, you can still watch documentary footage from 1964 of Nkoloso and his team training in Zambia on YouTube. A group of young men and women, dressed unassumingly and mostly barefoot, jump up and down, clapping their hands in front of a banner reading “zambia space academy.” The extended footage shows a young trainee being slotted into a metal cylinder, then raised up, his head poking out like a hapless turtle; another floating down a stream in a drum; Mwamba on a swing, wearing a bomber jacket, pumping her legs and smiling. The leader of these exercises wears an army helmet and a cape over high-waisted pants, a dress shirt, and tie. A British reporter takes Nkoloso aside to interview him. “Yes, this is the rocket-launching site, and my rocket is just here,” he says, gesturing matter-of-factly to an upright cylinder with an egg-shaped hole for breathing. “I will fire it from Lusaka and it will go straight to the moon, based on how much money I’ve got.” The reporter turns to the camera and remarks, laconically, “To most Zambians, these people are just a bunch of crackpots, and from what I’ve seen today, I’m inclined to agree.”

In his 1965 book “The New Unhappy Lords,” the British conservative A. K. Chesterton used Nkoloso as evidence of the folly of granting independence to African nations. “The masquerade of the African in the guise of a politician able to take over the running of a modern state . . . has nowhere been demonstrated in a more ludicrous light than in Zambia,” he wrote. “What other country in the world, for example, boasts a Minister of the Heavens?” This attitude toward the Zambian Space Program has persisted alongside the paeans to the eccentric genius. Over the years, Nkoloso has been called “an amiable lunatic,” “a court jester,” and “Zambia’s village idiot.” His name still crops up in compilations like “Never in a Million Years: A History of Hopeless Predictions” and “Dumb History: The Stupidest Mistakes Ever Made.”

Of everything I’ve read on Nkoloso, the 1964 series of articles by the San Francisco Chronicle columnist Arthur Hoppe best captures the tonal ambiguity of the Zambian Space Program. Hoppe described Nkoloso as “an engaging if somewhat insane man” with a “disarming grin,” and Matha as “a demure, well-rounded young lady with a charming smile.” Hoppe asked Nkoloso what Matha’s twelve cats were for:

“Yes, please,” he said, nodding. “Partly, they are to provide her with companionship on the long journey. But primarily they are technological accessories.”

Technological accessories?

“Yes, please. When she arrives on Mars she will open the door of the rocket and drop the cats on the ground. If they survive, she will then see that Mars is fit for human habitation.” . . .

In answer to direct questions as to whether she found orbiting thrilling, valuable, or merely routine, [Mwamba] ducked her head shyly and giggled charmingly. She did volunteer, however, that it was “a bit worrisome.”

Hoppe’s dry wit resonates beautifully with the snippets of local voices he captured, including that of Violet Ndonga: “To go to the moon. It is for you Americans.” She made a gesture that “summed up Zambian public opinion of America’s $20 billion program to win the race to the moon so as to enhance our national prestige throughout the world. They think we’re out of our minds.” As Martin Luther King, Jr., pointedly remarked, in 1967, a country that had spent twenty billion dollars to put a man on the moon could just as well “spend billions of dollars to put God’s children on their own two feet, right here on Earth.”

In his 1995 memoir, Hoppe said that his fellow-journalists, covering the violence in the Congo next door, had mocked him roundly for covering such a trifle. He returned to America to letters excoriating him for “blatant racism in poking fun at uneducated Africans.” Hoppe was shocked. “The thought had never occurred to me. I believed it was the Africans who were satirizing our multi-billion-dollar space race against the Russians.” One of Hoppe’s fellow-journalists told him his series was “going to be the greatest Rastus story in the history of journalism.” Rastus is a minstrel character from Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus tales, which often featured the trickster Br’er Rabbit.

The Zambian version of this witty, wily hare is named Kalulu. He is constantly devising elaborate trouble for elephant and lion, the two mighty beasts competing for King of the Jungle. The Zambian artist Stary Mwaba told me that Nkoloso had named one of his rockets dkalu-1, after President Kaunda. I wondered if he had actually named it after Kalulu. In 1969, the Chicago Journalism Review asked the acting press officer of the Zambian Embassy in Washington, Phineas Musukwa, about Nkoloso. Musukwa said he was “the Pat Paulsen of Zambia,” referring to the American comedian who made a running gag of running for President. “Mr. Nkoloso is actually a very well-read person,” Musukwa said. “It was a big joke.” If it was, Nkoloso never broke character: as one reporter said, “Nkoloso really lives the Jules Verne-like character he has built up around himself.”

In 1964, Nkoloso wrote an Op-Ed about his space program that read to me like a parody of British colonialism in Africa, refracted through a paranoid Cold War sensibility. “We have been studying the planet through telescopes at our headquarters and are now certain Mars is populated by primitive natives,” he wrote. “Our rocket crew is ready. Specially trained spacegirl Matha Mwamba, two cats (also specially trained) and a missionary will be launched in our first rocket. But I have warned the missionary he must not force Christianity on the people if they do not want it.” Nkoloso accuses American and Russian operators of trying to steal his space secrets: “Detention without trial for all spies is what we need.

Perhaps the question is not whether the Zambian Space Program was satirical but why so few have imagined that it could be. Zambian irony is very subtle. “We don’t have a yes and a no,” a painter observed to me on a visit to Zambia last year for an artists’ workshop. “We have two yeses, and one of them means no.” The study of the history of black culture is full of theories about doubled or split identity, what W. E. B. Du Bois famously described as “the peculiar sensation” of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” Nkoloso seems to have possessed a comic version of this condition, the ironic dédoublement—the ability to split oneself—that Charles Baudelaire saw in the man who trips in the street and is already laughing at himself as he falls.

A couple of years after my first encounter with the Afronaut, I came across a 1988 interview with him in a Zambian magazine. In the interview, Nkoloso makes no mention of the space program; instead, he reminisces with evident relish about his days as a freedom fighter in Kaunda’s United National Independence Party, the nation’s ruling party until 1991. On the eve of Zambia’s independence, in 1964, Nkoloso says, he and his unip; comrades pulled a particularly seditious prank. They broke into the Lusaka mortuary, bribed an attendant with a five-pound note for the corpse of a white woman, smeared goat’s blood on it, and transported it to the crowded whites-only bar at the Ridgeway Hotel, in Lusaka. The lights went out just as they tossed the corpse on the floor. Nkoloso says, “I shouted to the whites who were busy dining, drinking and laughing, ‘White men, your time is limited! We have killed the wife of [Prime Minister] Welensky and we shall soon pounce on you!’” The expats reportedly scattered. Nkoloso and his men took their prize—beer from the bar—and sang “militant songs in favor of the political struggle.”

As I discovered when I next travelled to Lusaka, to visit family, Edward Festus Mukuka Nkoloso is most famous in Zambia as a revolutionary. He was born in 1919, in the north of Northern Rhodesia, a prince of the Bemba warrior tribe; as a child, he received the distinctive scars to the cheekbones that denote royal status. Nkoloso met Kaunda as a young man; like the future President, he had a missionary education, learning theology, Latin, and French. Nkoloso wanted to join the priesthood but was drafted to serve in the Second World War, for the British, as a member of the Northern Rhodesian Regiment. Over the course of stints in Abyssinia and Burma, he was promoted up through the ranks in the Signal Corps, the communications branch of the military.

Nkoloso’s education and military service receive short shrift in Western reportage from the sixties. I learned more about both from his son, Mukuka Nkoloso, Jr. (I’ll call him Mukuka to distinguish them), during a long conversation at his ancestral home, a sky-blue one-story house in Lusaka. A jolly, voluble man of seventy, Mukuka was wary—“they write false stories about my father, they don’t tell the truth”—but keen to set the record straight. He told me that his father’s interest in science had begun during the war, under the tutelage of “a certain Mr. Montgomery, a white man,” who told him how to operate a microscope. But when Nkoloso returned from the war, the colonial administration denied him a permit to found his own school. He opened it anyway, and was prosecuted. Like black veterans around the world, Nkoloso had discovered that fighting for white men did not grant him a better life back home. “We are entirely forgotten,” he wrote, on behalf of African ex-servicemen, in a letter to the editor of The Northern News.

Nkoloso drifted between secondary schools around the country, teaching Latin, science, and math. One day, Nkoloso and some fellow-teachers were having lunch at his home when a new British education official came by. A kerfuffle ensued about whether the Africans had the right to take a lunch break. According to Mukuka, Nkoloso overturned the lunch table in anger, saying, “You are now hindering our human rights.” He led his entire school on a protest march to the Education Office. He was fired.

Nkoloso’s next job was as a salesman for the pharmaceutical company Lever Brothers, in Ndola, the boomtown of the copper-mining district. At the time, the Copperbelt was one of the most politically contested parts of the colonial territory then known as the Federation. The second Prime Minister of the Federation, Roy Welensky, was determined to hold onto the valuable mines in the north rather than handing power over to the blacks. The veterans and miners in the Copperbelt had other ideas. Nkoloso, already the head of a local veteran’s group, joined the Ndola Urban Advisory Council, one of the few institutions that gave Africans a voice, if not exactly a say in their governance.

In 2015, I went to the National Archives of Zambia, to see the records from the council’s monthly meetings. The typed notes, held together with rusty staples, reveal a young Nkoloso eager to promote his progressive ideas and showcase his education. He spoke against raising the Native Tax and asserted that the colonial federation protected “the interests of the white people” while Africans remained “drawers of water and labourers.” He advocated for a maternity clinic, a welfare hall, and an industrial and technical college that would lead to “equal pay for equal work.” In 1955, one year after Brown v. Board of Education in the U.S., Nkoloso proposed “an Inter-Racial School in this country as an experiment in this multi racial society.” He suggested that it was “inevitable destiny for this multi racial society to become dialectic in the struggle for survival.” Somewhere along the way, the Afronaut had been exposed to Marx.

Nkoloso soon gained a reputation as a political agitator in the Copperbelt. As the Zambian historian Walima T. Kalusa notes in an article about colonial conflict in the area, in 1956, Nkoloso stormed into the district commissioner’s office to protest against a European foreman’s exhumation of African graves. Having established himself as a troublemaker, Nkoloso later got caught up in a sweeping arrest of trade unionists. Upon his release, he was designated a “restricted person” and sent back to his home district, Luwingu, in a rural part of the country. There he became a district president of the African National Congress, a political party that was formed in 1948 to represent African interests in the colonial protectorate.

Mukuka painted a fierce portrait of the cult of personality that sprang up around his father as a freedom fighter. Nkoloso wore a blood-red robe and long dreadlocks as emblems of mourning for those slain under colonial rule. His followers compared him to Jesus, “who never cut his hair when he was preaching,” to John the Baptist, to Elijah. Nkoloso, a former seminary student, would perform baptisms, after which, Mukuka said, he would hand the newly converted membership cards to his political party. M. R. Mwendapole reports in his personal history of the Zambian trade unions that he and Nkoloso disguised themselves as women to avoid detection. Mukuka confirmed this, saying that Nkoloso, having “camouflaged” himself as a woman, would walk up to colonial officers and query them about this Nkoloso fellow, much to the amusement of the villagers in Luwingu.

On a hunch, I asked the archivists for a folder catalogued as “Luwingu Disturbance 1957.” It contained a jumble of original and photostatted letters and reports from the British government, A.N.C. officials, the colonial administration, and Nkoloso himself. The records, compiled for an official inquiry, revealed that Nkoloso had organized a large-scale civil-disobedience campaign against both the colonial administrators and the rural chiefs (the so-called Native Authorities). Africans refused to work as carriers, food servers, and census takers; they ignored orders to cultivate their fields. The local chief issued a summons for Nkoloso’s arrest. Nkoloso disappeared into the bush. After a six-day manhunt, witnesses said, he finally walked toward the officers and “straightened his arms forward ready for hand-cuffing.” But his supporters interfered, a riot began, and Nkoloso fled again. He was captured in the dambo, or wetlands.

The documents I read suggested starkly conflicting versions of what happened next. Nkoloso claims that an officer “deliberately, and willfully, grabbed and took me by the neck and thrust me into the river pool with his full intention to drown me.” Black kapasus injured him, he writes, when they shaved his head and beat him “with sticks on the lumbar side of my body causing internal batteries and very injurious internal maims, lacerating the nerves.” The colonial administrators deny these accusations, saying that the cuts to his head and his tumble into the water were accidental, and that he had merely fallen into “a state of collapse.” They call Nkoloso “well-educated but unbalanced” and a “puppet dictator.”

Nkoloso’s letters from prison display both his education and his flair for rhetoric. (In one, he reports that the district commissioner, “unlike the pure English blooded Englishman,” had commanded a group of school children “to sneer, and jibe, and jeer” at him, enacting “a political mockery drama like that of, ‘Ecce. Homo—Behold the Man, behold your Congress Chief!’ ”) He made sure that these reports of his arrest reached Kaunda, who was in England at the time, sponsored by the British Labour Party to learn about the parliamentary system. The A.N.C. telegrams that arrived on Kaunda’s desk in London alleged that Nkoloso had been taken in “nearly dead,” his parents “beaten to death,” and his female supporters physically and sexually assaulted. His aunt, who was arrested alongside him, had died in prison about two weeks after her arrest. Kaunda placed these reports, with all their incendiary details, into the hands of British officials in London. A rebellion in a small African village had exploded across the world and landed messily in the lap of the Empire.

Kaunda told his friend’s story in his pamphlet “Dominion Status for Central Africa?,” published in 1958 by the left-wing Union of Democratic Control. Soon after, Kaunda founded the new United National Independence Party (unip) responsible for the so-called Cha-Cha-Cha uprising (“we will make the imperialists dance to our tune”), a civil-disobedience campaign involving protests, arson, and road blockages. During this contentious period, the British repeatedly arrested unip leaders, including Nkoloso. Mukuka told me that, during one stint in prison, his father had dumped a bucket of urine and ashes on a prison guard’s head. Nkoloso became the self-anointed “camp kommandant” for unip’s meetings in the bush to plan the new government. Later, he was appointed the party’s “National Steward,” serving as a kind of hype-man for Kaunda at rallies as the country moved toward independence.

Mukuka had been a member of the unip Youth Brigade in the early sixties, and said that his father had started recruiting his space cadets from this organization, as well as from local schools. Mukuka had briefly participated in the space program as a teenager and remembered rolling downhill in an oil drum. “I was scared because you feel sometimes you can suffocate,” he told me. He seemed to take his father’s program seriously: “People were saying no, he’s mad, exaggerating. But, no, he’s a scientist, this is science.” Mukuka claimed that his father wasn’t just training the cadets for space travel, though; Nkoloso was also testing their “readiness for independence” in a political sense. “He was teaching for the program, but hidden from the British government. Teaching the youth so they could be active.” Before they had become astronauts, Mukuka said, Matha Mwamba and Godfrey Mwango had travelled to Tanzania to broadcast political propaganda when it was censored during Cha-Cha-Cha. “The Youth Brigade, you’d find in the morning ‘Vote unip’ written in paint on the tarmac,” Mukuka said. They even used explosives: “making bombs, burning bridges,” using “black cloth—they would put it in a sack, then they would mix it with petrol or paraffin, then they burn it.”

Describing all this subversive political action, Mukuka grew animated. “Miss Burton,” he said, snapping his fingers. “In Ndola, she was killed.” He was referring to one of the most famous moments of the Cha-Cha-Cha campaign. On May 8, 1960, a group of unip cadres in the Copperbelt had attacked a white British expatriate, Lilian Margaret Burton, by stoning her car and setting it on fire. Despite her deathbed appeal against retaliation, the accused were hanged for murder. “You know who killed her?” Mukuka said. “The astronauts, the scientists, the people who made bombs and some other things.” He imitated the sound of an explosion. “A bomb in her car. So when you wanted to jump in the car? Explodes!”

The space program, Mukuka seemed to suggest, was both a real science project and a cover. After independence, Nkoloso served as President Kaunda’s “Special Representative” at the African Liberation Center, a safe house and a propaganda machine for freedom fighters in other still-colonized nations on the continent: Angola, Southern Rhodesia, Mozambique, and South Africa. His son said that, beyond his management duties, Nkoloso gave military training to “those freedom fighters, they used to call them guerrillas,” in Chunga Valley—the erstwhile headquarters of the Zambian National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy. Zachariah Zumba, a colleague of Nkoloso’s at the Liberation Center, confirmed that freedom fighters had been trained “in the bush,” and that his astronauts had been drawn from the Youth Brigade. Zumba hinted that they may have served as bodyguards for Nkoloso, who was “a very feared man.”

Andrew Sardanis, a Greek-born journalist and businessman who participated in the independence movement, remembered Nkoloso differently. In the early sixties, Sardanis said, “everybody loved him, but at that stage, he was not being taken seriously . . . He was insane. Not a normal person.” Sardanis attributed this to what happened in Luwingu. “He was arrested and tortured. The Northern Rhodesian police tortured him. And after that, he lost it.” The Zambian ambassador to the U.N. at the time, Vernon Mwaanga, recalled that the reporters who flocked to interview Nkoloso “looked at him more in jest than in seriousness.” But he felt that the older members of unip respected Nkoloso as a veteran freedom fighter, and that the younger ones were inspired by his passion. “He was a very intelligent man,” Mwaanga said. “He was not a fool. He knew what was happening. He knew what was going on. Although my wife still thinks that he was crazy.” Mwaanga had a notion that Nkoloso had been invited to visit a nasa base, which lent some credence to a 1974 letter I’d found in the archives from Nkoloso, thanking the government for sending him “to witness the launching of Appollo [sic] 16.” (In the margins of the letter, there is a hand-scrawled note saying that his words appear “conceived in the realms of fantasy and imagination.”)

Last June, I interviewed former President Kaunda in his personal office, in the Leopards Hill neighborhood of Lusaka. Kaunda, who is ninety-two years old, was dignified and sharp, if a little hard of hearing. Nkoloso had been “quite politically active when we were fighting for independence,” he said, and “a useful servant to the nation.” When I mentioned the space program, Kaunda laughed. “It wasn’t a real thing,” he said. “He wasn’t a scientist, as such. But he used to do some—I can’t say ‘funny things,’ but many people enjoyed themselves in what he was talking about . . . It was more for fun than anything else.”

Once unip was established as the ruling party of the new nation, Mukuka said, Nkoloso was gradually relegated to the outskirts of government. “He was supposed to be Minister of Defense in the new government,” Mukuka said. “Now, unfortunately, they sidelined him.” Nkoloso drifted through what amounts to a series of sinecures. In his sixties, he went to law school at the University of Zambia, but the degree he earned, in 1983, did not yield better circumstances.

A year later, Nkoloso was working as the chief security officer for an industrial-development company outside of Lusaka. “It is too low for me and I don’t want to talk about it,” he told a Zambian reporter in one of his last interviews before his death, in 1989. He was more eager to discuss his “scientific madness” for space travel. “I have not abandoned the project,” he said. “I still have the vision of the future of man. I still feel man will freely move from one planet to another.”