PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Tortoise v hare: Is China challenging the United States for global leadership?

| BEIJING | THE ECONOMIST

Xi Jinping talks of a “China solution”, without specifying what that means

AS DONALD TRUMP prepares to welcome Xi Jinping next week for the two men’s first face-to-face encounter, both countries are reassessing their place in the world. They are looking in opposite directions: America away from shouldering global responsibilities, China towards it. And they are reappraising their positions in very different ways. Hare-like, the Trump administration is dashing from one policy to the next, sometimes contradicting itself and willing to box any rival it sees. China, tortoise-like, is extending its head cautiously beyond its carapace, taking slow, painstaking steps. Aesop knew how this contest is likely to end.

AS DONALD TRUMP prepares to welcome Xi Jinping next week for the two men’s first face-to-face encounter, both countries are reassessing their place in the world. They are looking in opposite directions: America away from shouldering global responsibilities, China towards it. And they are reappraising their positions in very different ways. Hare-like, the Trump administration is dashing from one policy to the next, sometimes contradicting itself and willing to box any rival it sees. China, tortoise-like, is extending its head cautiously beyond its carapace, taking slow, painstaking steps. Aesop knew how this contest is likely to end.

China’s guiding foreign-policy principle used to be Deng Xiaoping’s admonition in 1992 that the country should “keep a low profile, never take the lead…and make a difference.” This shifted a little in 2010 when officials started to say China should make a difference “actively”. It shifted further in January when Mr Xi went to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, and told the assembled throng that China should “guide economic globalisation”. Diplomats in Beijing swap rumours that a first draft of Mr Xi’s speech focused on the domestic economy, an uncontroversial subject that Chinese leaders usually like to talk about abroad. Mr Xi is said to have rejected this version, and brought in foreign consultants to write one dwelling more on China’s view of the world. Whether this story is true or not, the speech was strikingly international in tone and subject matter.

A day later Mr Xi made it clear whom he had in his sights. At the UN in Geneva, he talked about a “hegemon imposing its will on others” and warned America about a “Thucydides trap”—the disaster that befell ancient Greece when the incumbent power, Sparta, failed to accommodate the rising one, Athens. In February Mr Xi told a conference on security in Beijing that China should “guide international society” towards a “more just and rational new world order”. Previously Mr Xi had ventured only that China should play a role in building such a world.

Your consensus is nonsense

There was a time when America was urging China to step up its global game. In 2005 Robert Zoellick, then America’s deputy secretary of state, urged China to become a “responsible stakeholder” in the international system. But nothing much happened. After the financial crisis of 2008 there was excited talk in China and the West about a “China model” or “Beijing consensus”. This was supposedly an alternative to the so-called Washington consensus, a prescription of free-market economic policies for developing countries. But those who promoted a China model did not say that it should be adopted by other countries, only that it was right to reject what they saw as a one-size-fits-all Washington consensus. Is there more to it this time? Is China challenging America for global leadership?

To answer that, it is important to begin with the way China’s political system works. Policies rarely emerge fully formed in a presidential speech. Officials often prefer to send subtle signals about intended changes, in a way that gives the government room to retreat should the new approach fail. The signals are amplified by similar ones further down the system and fleshed out by controlled discussions in state-owned media. In the realm of foreign policy, all that is happening now.

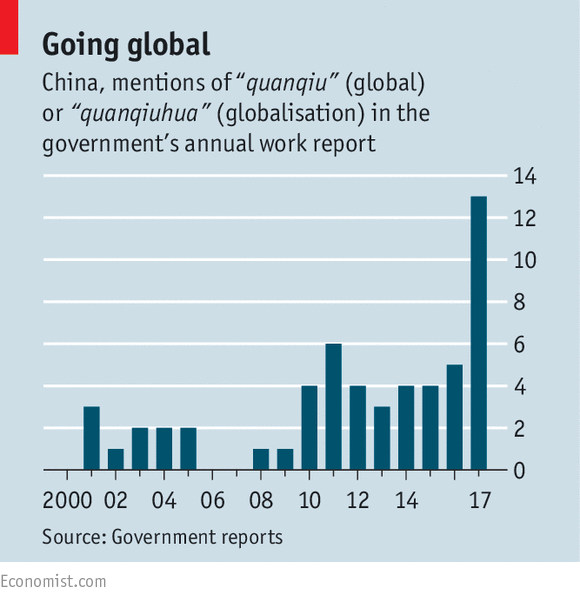

Soon after Mr Xi’s comments in Davos and Beijing, the prime minister, Li Keqiang, gave his annual “work report”—a sort of state-of-the-nation speech. It included an unusually long passage about foreign policy and mentioned quanqiu (meaning global) or quanqiuhua (globalisation) 13 times. That compares with only five such mentions last year (see chart).

As is their wont, state-run media have distilled the new thinking into numerical mnemonics. They refer enthusiastically to Mr Xi’s remarks on globalisation and a new world order as the “two guides”. And they have begun to discuss the makings of an idea that, unlike the old one of a China model, the country would like to sell to others. This is the so-called “China solution”. The phrase was first mentioned last July, on the 95th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. Mr Xi’s celebratory speech asserted that the Chinese people were “fully confident that they can provide a China solution to humanity’s search for better social institutions”. The term has gone viral. Baidu, China’s most popular search engine, counts 22m usages of its Chinese rendering: Zhongguo fang’an.

No one has defined what the China solution is. But, whatever it means, there is one for everything. Strengthening global government? There is a China solution to that, said the People’s Daily, the party’s main mouthpiece, in mid-March. Climate change? “The next step is for us to bring China’s own solution,” said Xie Zhenhua, the government’s special climate envoy, in another newspaper, Southern Metropolis. There is even a China solution to the problem of bolstering the rule of law, claimed an article in January in Study Times, a weekly for officials. Multi-billion-dollar investments in infrastructure in Central Asia are China’s solution to poverty and instability there. And so on. Unlike the China model, which its boosters said was aimed at developing countries, the China solution, says David Kelly of China Policy, a consultancy, is for everyone—including Western countries.

This marks a change. Chinese leaders never praised the China model; its fans were mainly Chinese academics and the country’s cheerleaders in the West. (Long before the term became fashionable, Deng advised the president of Ghana: “Do not follow the China model.”) Most officials were wary of it because the term could be interpreted as China laying down the law to others, contradicting its policy of not interfering in other countries’ internal affairs. In contrast, it was Mr Xi himself who broached the idea of the China solution. His prime minister included it in his work report. China now seems more relaxed about bossing others around.

This reflects not only the determination of the leadership to play a bigger role, but a growing confidence that China can do it. China’s self-assurance has been bolstered by what it sees as recent foreign-policy successes. Last year an international tribunal ruled against China’s claims to sovereignty in much of the South China Sea. But China promptly persuaded the Philippines, which had brought the case, implicitly to disavow its legal victory, eschew its once-close ties with America and sign a deal accepting vast quantities of Chinese investment. Soon after that Malaysia, another hitherto America-leaning country with maritime claims overlapping those of China, came to a similar arrangement. China’s leaders concluded that, despite the tribunal’s ruling, 2016 had been a good year for them in the South China Sea.

It was certainly a notable one for Mr Xi’s most ambitious foreign policy, called the “Belt and Road Initiative”. The scheme involves infrastructure investment along the old Silk Road between China and Europe. The value of contracts signed under the scheme came within a whisker of $1trn last year—not bad for something that only started in 2013. Chinese exports to the 60-odd Belt and Road countries overtook those to America and the European Union. In May Mr Xi is due to convene a grand summit of the countries to celebrate and advertise a project that could one day rival transatlantic trade in importance.

But talk of “guiding globalisation” and a “China solution” does not mean China is turning its back on the existing global order or challenging American leadership of it across the board. China is a revisionist power, wanting to expand influence within the system. It is neither a revolutionary power bent on overthrowing things, nor a usurper, intent on grabbing global control.

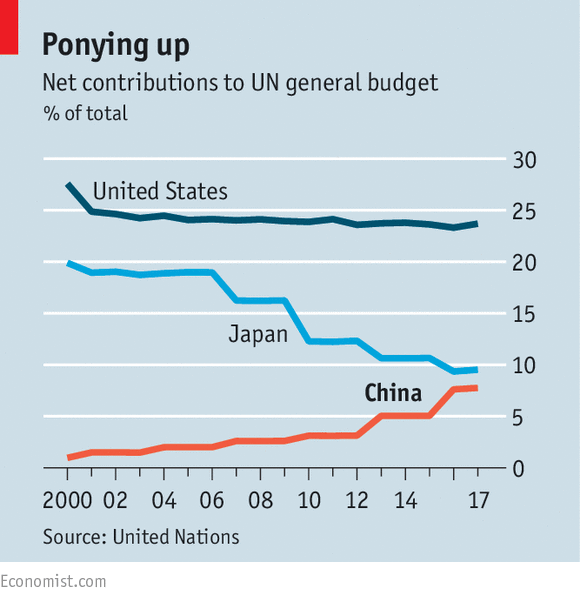

China is the third-largest donor to the UN’s budget after America and Japan (see chart) and is the second-largest contributor, after America, to the UN’s peacekeeping. Last year China chaired a summit of the Group of 20 largest economies—it has an above-average record of complying with the G20’s decisions. Recently it has stepped up its multilateral commitments. In 2015 it secured the adoption of the yuan as one of the IMF’s five reserve currencies. It has set up two financial institutions, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank, which are modelled on traditional ones such as the World Bank. Global rules on trade and finance, it seems, are too important for Mr Xi not to defend.

China is becoming a more active participant in the UN, but it is not trying to dominate it. It reacts to, rather than initiates, sanctions policy towards North Korea. And despite its own extensive anti-terrorist operations at home, it shows little interest in joining, let alone leading, operations against Islamic State.

There are domestic constraints on Mr Xi’s ambitions. China’s vast bureaucracy is resistant to change in foreign policy, as in everything else. During a recent trip to Australia the foreign minister, Wang Yi, said China had “no intention of leading anybody”. He was not contradicting Mr Xi, but neither was he echoing the president’s desire to guide a new world order. Ding Yifang of the Institute of World Development, a think-tank in Beijing, is similarly cautious about the China solution. “We don’t have universal ideals,” he says. “We are not that ambitious.”

Globalism with Chinese characteristics

So what might China’s unassuming new assertiveness mean in practice? A template can be found in climate-change policy. China was one of the main obstacles to a global climate agreement in 2008, but now its words are the lingua franca of climate-related diplomacy. Parts of a deal on carbon emissions between Mr Xi and Barack Obama were incorporated wholesale into the Paris climate treaty of 2016. China helped determine how that accord defines what are known as “common and differentiated responsibilities”, namely how much each country should be responsible for cutting emissions.

As chairman of the G20 last year, Mr Xi made the fight against climate change a priority for the group. But China’s clout at that time was bolstered by its accord with America. Now Mr Trump is beginning to dismantle his predecessor’s climate policies. Li Shou of Greenpeace says China is therefore preparing to go it alone as Mr Xie, the climate envoy, said in January that it was prepared to do. It may be that a “China solution” to climate change will be the first practical application of the term.

Soon after Mr Xi’s speech in Davos, Zhang Jun, a senior Foreign Ministry official, put his finger on China’s changing place in the world. “I would say it is not China rushing to the front,” he told a newspaper in Hong Kong, “but rather the front-runners have stepped back, leaving the place to China.” But officials have far fewer qualms than Deng did about being at the front. “If China is required to play a leadership role,” says Mr Zhang, “it will assume its responsibilities.”