PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Ed Helmore | Sunday 2 April 2017 | The Guardian

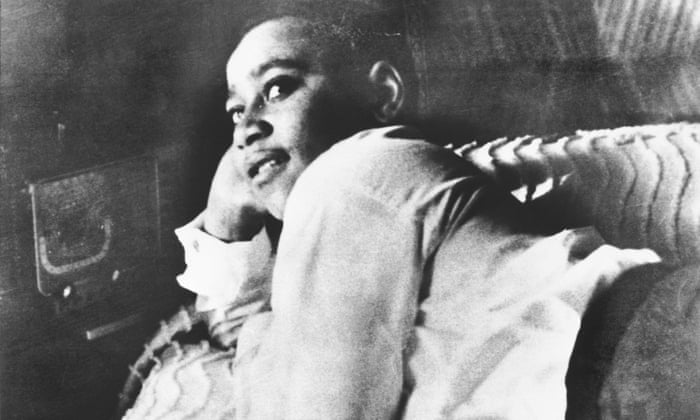

New York art world bitterly divided over ‘cultural appropriation’ of 1955 photograph of murdered 14-year-old Emmett Till

It is one of the most powerful images to emerge from the racism that infected the southern states of America in the 1950s – the photograph of a badly beaten 14-year-old boy, lynched after being falsely accused of flirting with a white woman, lying in a funeral casket.

Now protests over a painting based on the photograph, included in a New York museum show, are dividing the city’s art world amid claims of racist exploitation and censorship.

At the centre of the battle over cultural appropriation is artist Dana Schutz’s expressionist painting Open Casket (2016), a gruesome depiction of Emmett Till, lynched in Mississippi in 1955.

The painting, on display at the Whitney Biennial exhibition, initially drew swift condemnation from critics who claimed Schutz, who is white, was taking advantage of a defining moment in African American history.

African American artist Parker Bright stood in front of the painting with Black Death Spectacle written on his T-shirt, and a young British artist, Hannah Black, accused Schutz of having “nothing to say to the black community about black trauma”, demanding that the work “be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum”.

Against a backdrop of increasing anxiety over artistic censorship and de-funding of the arts under the Trump administration, Schutz’s critics faced a barrage of allegations of censorship. Marilyn Minter, a leading liberal and feminist voice on the New York arts scene, posted on Facebook: “The art world thinks Dana Schutz is the enemy? The left is eating its young again. Censorship from the left really sucks!”

Painter Kara Walker noted that paintings last longer than the controversy they can generate. “I say this as a shout [out] to every artist and artwork that gives rise to vocal outrage. Perhaps it too gives rise to deeper inquiries and better art. It can only do this when it is seen.”

Writer Gary Indiana called an open letter from Black, signed by more than two dozen other African American artists or art-world workers, “cliche-riddled, race-baiting demagoguery”.

Schutz, 40, told the website Artnet that she made the painting in response to the police shootings of unarmed black men over the summer of 2016. “It’s a problematic painting, and I knew that getting into it.”

The Schutz controversy comes as UN human rights investigators warned last week of “an alarming and undemocratic trend” in the US as 19 states have introduced legislation that would curb freedom of expression and the right to protest since Donald Trump’s election.

At the other extreme, there are a mounting number of incidents of cultural appropriation. Rachel Dolezal, a former leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, who caused controversy last year when she admitted she was born to white parents but identified as black, last week published a memoir in which she recalled pretending to be a dark-skinned princess in the Sahara in order to “escape the oppressive environment I was raised in”.

Fashion designer Tory Burch was forced to apologise for a video ad entitled Tory Story: An American Road Trip that featured three white women, including British model Poppy Delevingne, dancing to Juju on That Beat by black rappers Zay Hilfigerrr and Zayion McCall. “It’s no surprise to us to see a fashion company using solely white models in an ad but it was a bit of a shock to see Delevingne and the other two models dancing along to the song without out one black model included,” noted Essence magazine.

But neither compare to the appropriation of the photograph of Till, mutilated in his coffin, that helped to kickstart the civil rights movement. Last week members of Till’s family met US attorney general Jeff Sessions and asked him to enforce a law that enables prosecutions in decades-old civil rights murder cases.

Civil rights leaders fear the Trump administration might not seek to enforce the Emmett Till Civil Rights Crimes Act that allows the Department of Justice and FBI to reopen unsolved civil rights cases that occurred prior to 1980.

In a book published earlier this year, the woman who accused Till of making sexual advances on her, Carolyn Bryant Donham, acknowledged that her testimony was fabricated. After being acquitted of the murder by an all-white jury, Donham’s first husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother, JW Milam, admitted to killing Till in a paid interview for Look magazine. The case was reopened in 2004 but federal prosecutors concluded that it could not be heard due to the statute of limitations.

After the meeting with Sessions, Till’s cousin Deborah Watts told MSNBC that Sessions had agreed the law should be enforced. “There are other families out there that have no justice. There’s been no adjudication, no answers. And he agreed with us that that should occur.”

Schutz’s picture, with its canvas raised and gashed to suggest Till’s horrific wounds, will remain on display, Whitney museum officials say.

The photograph of Emmett Till is important to American history, says African American culture writer and historian John Jennings, but “Schutz has the right to make art and it should not be destroyed. But we should be careful about the conversations we have.”

Till’s mother, Mamie Till Bradley, authorised the original photography because she “wanted the world to see what those men had done to her son”. “The re-mediation of it does something very different than was initially intended,” Jennings says. “I applaud the Whitney for allowing people to protest the piece, but what happens now? It’s an opportunity for discussion.”