PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

The road less taken: Migration from Eritrea slows

| KHARTOUM | THE ECONOMIST

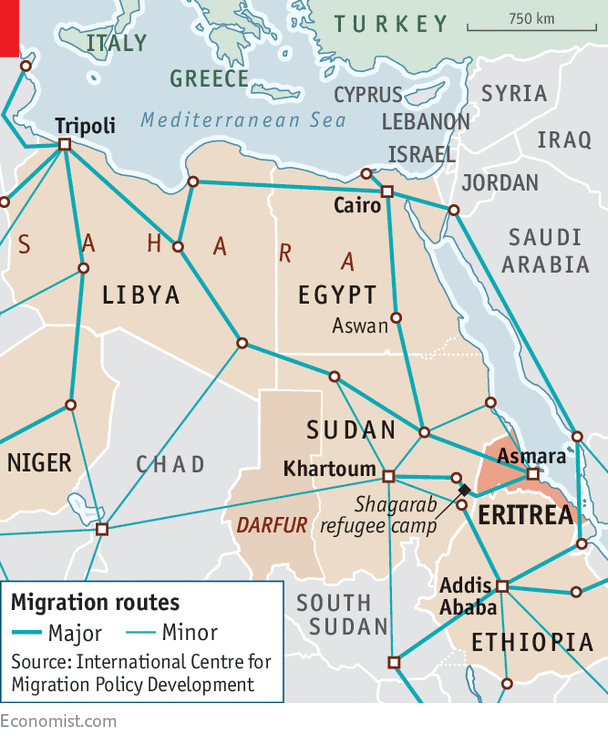

Young people fleeing indefinite military service are encountering more obstacles on the route through Sudan

IN JERIF, a district of Khartoum, young Eritreans listen to Tigrinya pop music in dimly lit restaurants, or watch football at an oppressively hot community centre supported by their government. They are mostly male, and almost all have fled compulsory, indefinite military service on behalf of their despotic government. Most are working, or waiting for relatives to send money, so they can leave for Europe.

But the lads in Jerif will find their journey harder than their predecessors did. The number of Eritreans successfully completing each stage of the trip across the Sahara and the Mediterranean via Sudan appears to have declined in recent years. Border crossings fell by almost two-thirds to 9,000 between 2010 and 2016, according to the UNHCR, the UN’s refugee agency (the real figures will be far higher, however: plenty of Eritreans get into Sudan undetected). A smuggler says he sent 150 migrants from Khartoum to Libya and Egypt last year, down from 300-400 in 2014 and 2015. And 21,000 Eritreans made it to Europe in 2016, down from more than 39,000 the previous year when they were the largest group of migrants arriving in Italy.

European governments have realised that voters are fed up with people fleeing war and poverty across the Mediterranean. European Union money has persuaded transit countries from Turkey to Niger to curb the flow. Eritreans are also deterred by the risk of being kidnapped near the dangerous Eritrea-Sudan border.

Still, trafficking in the border region has not stopped. Digin, a soft-spoken 18-year-old, says he was chained up for 42 days by his kidnappers, after escaping from an Eritrean military training camp. After his family paid a ransom he was driven to Shagarab, a refugee camp close to the border.

Only a third of the Eritreans whom the UNHCR records crossing into Sudan will register as refugees. And within a few months, four-fifths of those will have sneaked out of Shagarab to meet a car that will take them to Khartoum. There they will meet a samsara (smuggler) who arranges the onward journey, once the migrants have the money.

The Libyan border with Sudan, in turn, is not as porous as it was. In the past year hundreds of Eritreans and Ethiopians have been caught by Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a group made up of the militia formerly known as the janjaweed that inflicted genocide on black Africans in Darfur in the mid-2000s. The captured Eritreans were deported. “The road to Libya is still working,” says a smuggler. “But it’s very dangerous.”

Eritreans are increasingly avoiding Libya, which is racked by civil war. Going via Egypt, usually by car and then train, does not guarantee success either. Meron Estefanos, a Swedish-Eritrean activist who tries to help captured Eritreans, says she now receives more calls from relatives of people imprisoned in Egypt, than from those kidnapped by gangs in Libya.

Others are heading north from Sudan, among them Sudanese themselves, especially Darfuris; the children of Eritreans who fled the war with Ethiopia in the 1990s; and Ethiopians. The EU is spending at least €115m in Sudan, mainly on things like education and nutrition, to try to give would-be migrants reasons to stay. EU officials say the funds, which started being approved in April 2016, will be handled by international agencies. One says they are “discussing” not “negotiating” with a government whose president of 28 years, Omar al-Bashir, is wanted by the International Criminal Court for allegedly ordering the slaughter in Darfur. But the arrests by the RSF, and recent round-ups of long-term Eritrean residents in Khartoum, suggest that the regime wants to show that it can curtail migration.

As long as the repressive Eritrean and Sudanese governments remain in power, people will try to get to Europe, however perilous the odyssey. Some women reportedly take contraception, expecting to be raped. Others learn parts of the Koran in case they are kidnapped by Islamic State in Libya. But many have stayed in Sudan long enough to see loved ones disappear in the desert or drown in the Mediterranean, and are loth to leave. If they were allowed to study and work, rather than being arrested, fewer would risk the onward trek.