PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

NO COUNTRY FOR BOYS

YEPOKA YEEBO:

Agbogbloshie is a vast, scorched field, right in the middle of Accra, Ghana, dotted with rusting hulks and heaps of scrap. Hundreds of people work here in what looks like hell: smashing, burning, hawking, eating, and joking. This is the place where thousands of tons of the world’s electronics go to die.

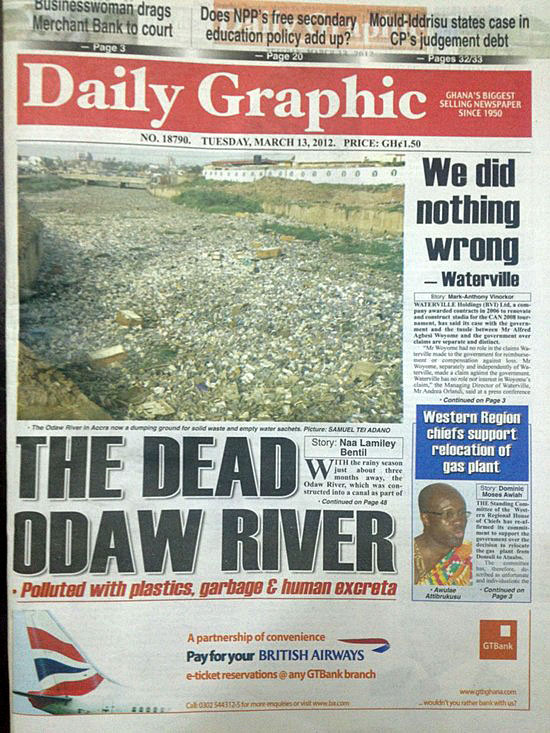

On the banks of the dead Odaw River at the very edge of Agbogbloshie, groups of young men tend fires set to burn the plastic off old copper cable. The ground is pillowy with tiny bits of charred plastic and metal, and still smoking hot after the fires are long gone.

A kid wearing a blue Adidas T-shirt, purple damask shorts, and flip-flops emerges from a cloud of black smoke, coughing. Inusa Mohammed is 13. His expression alternates between grave  concerns—he hasn’t made enough money, and it’s already mid-afternoon—and a beatific smile.

concerns—he hasn’t made enough money, and it’s already mid-afternoon—and a beatific smile.

He takes a deep breath and goes in search of more fuel. The bigger boys use tires to keep the fires going, but that’s professional-level scrapping. Inusa’s just out here on a Saturday trying to make enough money to pay for his junior-high-school exams. He doesn’t plan to make a career out of it: He’s going to get through school and join the Air Force.

This is the chaotic heart of one of the biggest economies in West Africa. A 15-minute drive from Parliament House, there is clamorous open-air production lines; factories churning out everything from paint to Pepsi; and the country’s biggest markets. Agbogbloshie is one of the largest, a mile-long strip of wholesale stalls where traders from all over West Africa sell pineapples, onions, cattle, and car parts by the truckload. In the early days, anything they couldn’t sell—rotten tomatoes, rusted-out car doors—got dumped on the marsh behind the market, attracting scavengers and savvy businessmen who could turn a profit from anything. Container-loads of trash from all over the country started coming straight here.

There were heaps of heavy machinery from local construction projects, hundreds of broken PCs, and a mountain of ozone-depleting fridges and freezers (so many that in 2012, the government banned all imports of used refrigerators—it hasn’t worked). This is how, in just 20 years, a lush mangrove swamp became one of the world’s biggest electronic waste dumps.

Inusa runs back to the riverbank with hunks of yellow insulation foam ripped out of an old fridge, and feeds them into the fire. His best friend, 14-year-old Kwesi Bido, cautiously pokes at the bundle of wires inside with the charred remains of a computer monitor. The foam burns up and the fire dies down. Both Kwesi and Inusa are in the equivalent of eighth grade. They come to Agbogbloshie after school and on weekends to make spending money and help pay their way through school. The scrap yards are populated by cautionary tales, dropouts trying to make enough to go back to school before they age out, arguing about improper fractions with the kids in crisp, pressed uniforms who walk through on their way home. High school isn’t free in Ghana. It’s supposed to be: It’s in the constitution, and the last three presidents promised to improve access to education, but not one got around to it.

Suddenly something explodes. Everybody near the fires goes quiet as a burning aerosol can soars through the air. It lands in the dirt about a foot away from Kwesi and Inusa. There’s a collective sigh of relief: Nobody’s hurt. People get hurt here all the time, though. The older boys’ hands are scarred from cuts and burns.

Inusa pulls on one grubby, heat-resistant glove, and gingerly picks through the smoldering bundle of wire, peeling off bits of melted plastic. Satisfied that he’s taken off enough to please the scrap dealer but left enough weight in the bundle, he picks up the entire thing and puts it in an old rice sack.

Up to 80 percent of all the electronic devices and appliances thrown away around the world may end up in dumps like Agbogbloshie. Some research suggests that the average American, for example, produces about 66 pounds [30 kg.] of electronic junk every year. This is hazardous waste—the cathode ray tube in just one old style computer monitor can contain almost seven pounds of lead—which makes it expensive to recycle. So hundreds of tons of this waste quietly disappears into a world of legitimate recycling companies, shady middlemen, and black market trash traders. Interpol says one of every three shipping containers inspected leaving Europe for the developing world is packed with illegal electronic waste.

Much of that ends up in urban mines like Agbogbloshie, and is processed by a workforce of young men with few tools, no safety equipment, and no training, then fed back into the global economy. When commodity prices were good, Chinese firms bought up pretty much everything, and scrap dealers made fortunes. It triggered a shortage that forced the government to ban exports of scrap iron and steel.

But now commodity prices are in the toilet, so everybody at Agbogbloshie is getting tight-fisted. Inusa and Kwesi are learning this the hard way, at the copper dealer’s ancient red Avery scale, a few cramped lanes away from the fires. Kwesi is adamant they brought in two pounds of copper, but the scrap dealer isn’t having it: It’s one. Kwesi and Inusa take the money: 7 cedi (about $2) for an hour of work.

Kwesi’s okay with earning his keep. He’s wearing his work uniform: jeans, a green polo shirt with Mandarin on the front and the name “Porosky” bleached into the back, and an abundance of caution. People keep getting hurt around here. He plans to join the Army, which—even at his age—he knows as the only functioning institution in Ghana. But it’s competitive, and he has to finish school for that. And finishing school costs money. So he keeps track of the scrap business in the know-it-all way 14-year-olds do.

He explains the hierarchy at Agbogbloshie. The best prices are at the copper scale: 7 cedi per pound, then it is brass, then aluminum, which is just 2 cedi per pound, the equivalent of about 60 cents. The least lucrative type of scrap here is the iron, which goes for almost nothing. Everything else he takes back to their base, a timber shed painted green, where a scrap dealer named Francis buys all the other, cheaper bits of random scrap his boys scavenge.

At the shed, Francis is hammering the pink wheels off part of a rusty white tricycle. Two other boys are using a mallet to chip away at a lump of metal pellets encased in concrete—the ballast from a road grader that one of the big scrap dealers took apart. Suddenly, the smallest kid in the place steps on a huge shard of glass, which slices through his flip-flop and his tiny foot. He whimpers as his toes turn into a bloody mess, then looks like he’s holding back a scream.

Francis rushes away and comes back with an old plastic Fanta bottle full of iodine and pours it over the kid’s foot. An older girl pours water over the kid’s second toe, split almost in half from top to bottom. Francis rips a strip off a rag and wraps up the toe while berating the kid in Twi: “I keep telling you, wear the boots.”

The kid limps off wincing and holding back tears, and comes back with the boots: one lace-up, one Ugg; both grubby, fur-lined and absurd in the 90-degree heat. Other kids point and laugh. There’s bright red blood all over the hard-packed earth.

There are graver hazards at Agbogbloshie. The electronic waste leaks lead, mercury, arsenic, zinc, and flame-retardants. They’ve been found in toxic concentrations in the air, water, and even on the fruits and vegetables at the wholesale market. Environmental campaigners say that many of the boys who have been smashing and burning for years are getting sick from the exposure and dying young.

Kwesi and Inusa don’t have time to worry about that. It’s time to go scavenging. They go off at a fantastic pace, dragging old stereo speakers tied to bits of string on the ground behind them. The speakers are magnetic, and they pick up random chunks of metal, bits of circuit board, scraps of wire, and at one point, the remains of a tape deck. Kwesi and Inusa drag their magnets past a guy stacking timber; past a pile of discarded CPU cases; past a huge, old-style projection television; past a heap of car doors; past rolls of fence wire, grills, and tires; past a bunch of guys portioning weed into white wraps while listening to old Indian music. Every so often, Kwesi and Inusa wipe the magnets clean with one hand, sifting the debris and dust in their palms until all that’s left is the good stuff, which they deposit in their sacks.

Kwesi finds 20 pesewa (about 6 cents) in the rubble; Inusa finds one whole cedi (about 20 cents). They go past a little girl selling water, and older boys sorting massive hulks of shiny copper wire. They go past women deep frying yams, and chickens scratching in the dirt. They drag, stoop, and sift; drag, stoop, and sift. The sacks start to get heavy as they round a corner and arrive right back at Francis’ scales. They weigh in at a total of 13 pounds, but Kwesi swears it’s more, and starts arguing with Francis.

Every week or so, depending on the markets, Francis sends a truck loaded with about five tons of scrap over to the nearby port city of Tema, where it’s weighed, separated by machines, and turned back into useful commodities. Right now, he gets about 710 cedi (about $220) for each truckload. The price is low, but everything’s messed up in Ghana right now. Construction projects are stalling, so nobody wants to buy the locally made iron rods and metal roofing sheets that keep scrappers like Francis in business. The government’s so broke it had to ask the International Monetary Fund for a bailout, the electricity blackouts now last 12 hours at a time, and inflation has suddenly made everything from food to school fees prohibitively expensive.

Inusa, impatient and worried about how little he’s made, races off around the scrap yards again, turning back to argue with Kwesi about the best route. Kwesi isn’t in such a rush. He keeps stopping to banter with the other boys, and dances with surprising grace to the music blasting from a stall.

They get to a clearing where two groups of teenagers are playing soccer. On the very edge of the pitch, Inusa sees two guys loading computer parts onto a hand truck, littering the ground around their shed with shiny nuts and bolts and bits of circuit board—the motherlode. Inusa makes a beeline for it. Kwesi tries to call him back. “They’ll beat him,” he says. The area around that shed belongs to those scrap dealers. Inusa must be crazy, he says in Pidgin: “This boy he craze, papa.” But Inusa slips by the guys unnoticed, scoops up handful after handful of fresh scrap, and comes back grinning.

Back at Francis’s place, they sift through the haul using the case of a fan like a sieve to get rid of the dirt. Then they play around, waiting for Francis to pay them. Someone finds a broken Phillips DVD player, and Kwesi puts the pieces back together. “I want to make money, so I can buy one,” he says. But that’s for when he makes a ton of money. Right now, he’s working for new shoes.

Francis cashes them out. Another 11 pounds, although Kwesi insists it’s 12. Still, he takes the money. They divvy up the cash, and Inusa is pissed. Kwesi made way more money than he did. Kwesi swears he’s been working longer, and brought in more scrap. Inusa doesn’t look convinced, but he forgets to stay angry as they walk back through Agbogbloshie. He’s looking forward to a wash. Both boys are completely covered in soot and dirt. Then there’s dinner, and studying to do. They stop to tease a girl who is hawking packets of water, then tumble off down the road, headed home.

For teenagers in Ghana, finding scraps in one of the world’s largest dumps is an after-school job.

Yepoka Yeebo is a reporter and photographer working primarily in West Africa. She’s written for Quartz, The Times, Newsweek, The Huffington Post, and Columbia Journalism Review, and watched the wires as a photo editor at TIME.com. She holds a masters degree from Columbia Journalism School, and a joint honours BA from Queen Mary College at the University of London, and City University Journalism School. Stories by Yepoka Yeebo The Bridge to Sodom and Gomorrah

Yepoka Yeebo is a reporter and photographer working primarily in West Africa. She’s written for Quartz, The Times, Newsweek, The Huffington Post, and Columbia Journalism Review, and watched the wires as a photo editor at TIME.com. She holds a masters degree from Columbia Journalism School, and a joint honours BA from Queen Mary College at the University of London, and City University Journalism School. Stories by Yepoka Yeebo The Bridge to Sodom and Gomorrah