PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

CONSTITUTIONS IN AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES

Tom Ginsburg and Alberto Simpser:

An old Soviet joke has it that a man goes into a restaurant and surveys the menu. “I’ll have the chicken,” he says, only to be told by the waiter that the restaurant is out of chicken. He asks for the beef, only to be told the same thing. Working his way through the menu, he is repeatedly told that the restaurant is out of the selected dish, until he gets upset and says, “I thought this was a menu, not a constitution.”

The joke captures the usual perception of dictatorial constitutions as meaningless pieces of paper, without any function other than to give the illusion of legitimacy to the regime. But this view raises a puzzle. Formal written constitutions are ubiquitous features of modem nation-states, and are found as often in autocracies as in democracies. The seventeen years required to d raft the recent constitution of Myanmar may have been exceptional, but there is no doubt that some authoritarians spend political effort on constitution making. Why would they bother to do so if the documents are meaningless? The standard answer that the constitution is a legitimating device begs the question: How can an obvious sham document generate any legitimacy?

CONSTITUTIONS AS SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS OF GOVERNING: Constitutions have a wide array of functions, and some of these functions are likely to be shared across both authoritarian and democratic regimes. A very central function of formal rules including constitutions is simple coordination. All regimes need institutions and need to coordinate on what institutions will play what role. Laying out the structures of government facilitates their operation because it prevents continuous renegotiation. A written constitutional text can thus minimize conflict over basic institutions for any regime. Furthermore, we know that certain institutions can facilitate coordination within the core of the governing elite itself. The Chilean constitution under Augusto Pinochet documents how, especially the Constitutional Tribunal, facilitated coordination among the various military branches that composed the junta. Coordination, then, is a ubiquitous need of government that can be facilitated by formal written constitutions, facilitating elite cohesion.

Augusto Pinochet documents how, especially the Constitutional Tribunal, facilitated coordination among the various military branches that composed the junta. Coordination, then, is a ubiquitous need of government that can be facilitated by formal written constitutions, facilitating elite cohesion.

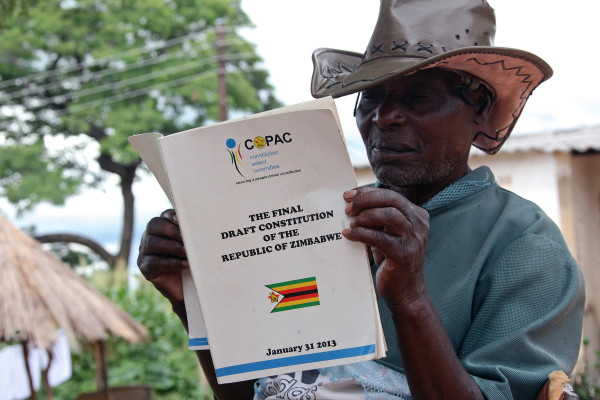

Authoritarian constitutions also can facilitate coordination by democrats at crucial moments of transition. When Zine el Abiclin e Ben-Ali of Tunisia fled his country in the Arab Spring of 2011, his prime minister briefly took over as president in defiance of the constitution. After several hours, it was decided that the formal provisions of constitutional succession should be followed, leading to the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Fouad Mebazza, taking office as a caretaker before elections could be organized. This simple coordination function can become extremely important at the end of authoritarian regimes, preventing conflict from spiraling out of control over basic institutions.

Other “standard” constitutional functions may also operate in both dictatorships and democracies. We know, for example, that constitutions help address problems of intertemporal credibility by making commitments endure across time. While authoritarians and democrats may differ in the precise character of the commitments they wish to undertake, the basic modality of entrenching certain policies to enhance credibility may be useful to all leaders. Military authoritarians, in particular, may use the opportunity of a constitution to set a time-line for a return to civilian rule, as well as the terms under which such a return may take place. Announcing such a project will raise the costs of violating the text of the constitution, and may also facilitate a period of “legitimate” authoritarian rule.

Constitutions may also be useful to set up institutions to control lower-level agents. All regimes need mechanisms to control agents, and the problem of gathering information on the activities of agents is an enduring one. There are many standard solutions to the problem: hiring a second agent to monitor the first (or otherwise improving detection and increasing punishment); selecting agents for loyally and affinity; structuring systems of hierarchical appeal to higher-level agents; and creating a powerful ideology that is internalized by the agents themselves so that they self-monitor.

Historical examples of government solutions to the agency problem include the imperial Chinese institution of the censorate, a separate branch of government to monitor the bureaucracy. This solution, however, creates the standard problem of “who guards the guardians?.” Imperial China was also an early pioneer in the hierarchical approach to the agency problem, utilizing what eventually became known as a Weberian bureaucracy with higher levels supervising that lower down. Max Weber celebrated it as the most technically efficient of government structures, but it is costly and creates its own problems of information flow. It also requires careful ex ante screening of potential agents to ensure loyalty. Ideology is another tool to enhance loyalty, and it is favored by some mass political parties and religious institutions such as the Catholic Church. It is difficult to sustain, though very effective when it is in high operation.

Jean Bodin, in The Six Books of the Republic (1576), was one of the first to explore how constitutions can help to resolve principal-agent problems via institutional design. Bodin notes that the French king adopted a solution of parliamentary immunity to help generate information about lower-level agents. The parliamentary representatives had an absolute right to bring complaints  about provincial agents of the king without fear of punishment. This was central to generating important information to provide more effective monarchical governance, a kind of early version of the “fire alarm” model of administrative law.

about provincial agents of the king without fear of punishment. This was central to generating important information to provide more effective monarchical governance, a kind of early version of the “fire alarm” model of administrative law.

Constitutional solutions to the agency problems also include institutions whereby a ruler ties his own hands. Doing so can be a means for enabling the powerful to enter into credible commitments. Roger Myerson‘s work is also important in understanding the emergence of constitutionalism generally and the utility of constitutional logic to authoritarians. In his study of the foundations of the constitutional state, Myerson provides a model in which, in equilibrium, it is in the autocrat’s interest to create a court of notables with the ability to remove him from power. “Without such an institutionalized check on the leader,” Myerson writes, “he could not credibly raise the support he needs to compete for power”. In a related model, Myerson focuses on the agency problem facing powerful rulers. In the model, a prince faces the possibility that his agents, the governors, could be corrupt or rebel against him. To prevent this, the prince must credibly assure governors that he will not unfairly cheat them.

James Fearon’s work points to another way in which constitutions might be beneficial to autocrats. Autocrats face the problem that the public cannot trust them to refrain from shirking or stealing, and therefore will periodically choose to rebel against the ruler. One way to address this problem is to adopt a constitution that provides for fair elections to be held regularly. Because the results of such elections aggregate and make public the citizens’ private information about the ruler’s performance, they make it possible for the ruler to be rewarded by the citizenry for governing well. This model again elaborates the common need for regimes—both democratic and autocratic—to facilitate information flows.

OPERATING MANUALS, BILLBOARDS, BLUEPRINTS, AND WINDOW DRESSING: Coordination, precommitment, and agency control are all essential governmental functions that can be played by various institutions, but constitutions are particularly good solutions that have become standard in the modern era. When a written constitution describes actual political practice, it is serving as what Adam Przeworski characterizes as an operating manual. The constitutional text describes how government is to function, allowing various players to cooperate by following its instructions. Przeworski’s particular puzzle is why the 1952 Polish constitution, framed at the apex of Communist power in Poland, accorded de jure authority to the government and not to the Communist Party.

Przeworski shows that, in so doing, the Communist Party framers chose to “rule against rules,” creating unnecessary difficulties for themselves. Przeworski’s discussion suggests that, in their role as operating manuals, constitutions provide some genuine constraints on leaders. Consistent with this, Jennifer Gandhi argues that authoritarian constitutions influence possibilities, in electoral authoritarian regimes, for opposition parties to join efforts in order to beat an autocrat at the polls. Opposition parties, she argues, will enter into a coalition with each other insofar as they can trust that, should their coalition win the election, whichever party is installed in the presidency will honor its promises to the other coalition partners. Gandhi’s key point is that constitutions determine the degree and kind of power associated with control of the presidency. The greater the power of the presidency as set out in the constitution, the less credible it is, ex ante that promises to coalition partners who do not control the presidency will be fulfilled in the future.

Beyond serving as operating manuals, constitutions can play several other roles that we characterize as billboards, blueprints, and window dressing. The billboard role is common to both dictatorships and democracies. Constitutions are advertisements—they seek to provide information to potential and actual users of their provisions. As authoritative statements of policy,  constitutions can also play a role in signaling the intentions of leaders within the regime to those outside of it. These audiences might be international written in part to signal capacity to engage on the international plane. Or the audiences may be domestic, consisting of the population that will be subject to the constitution.

constitutions can also play a role in signaling the intentions of leaders within the regime to those outside of it. These audiences might be international written in part to signal capacity to engage on the international plane. Or the audiences may be domestic, consisting of the population that will be subject to the constitution.

Sometimes, of course, the promises in constitutions are not accurate signals of policy, but pure fictions. This window dressing role of constitutions, aptly captured in the Soviet-era joke at the beginning of the article, is one in which the text is designed to obfuscate actual political practice. To use another Chinese example, the constitution promises its citizens’ freedom of speech and demonstration (Art. 35), freedom of religion (Art. 36), and the right to criticize the government (Art. 41). But these things are routinely violated in practice. North Korea’s constitution may be seen as a pure sham for guaranteeing its citizens “democratic rights and liberties” (Art. 64), though its list of rights is actually relatively limited compared to many other communist texts.

The point is that the extensive list of rights found in many totalitarian constitutions is hardly meant to provide for meaningful constraint on the state, or to signal government intents, but is instead a kind of “cheap talk” that adopts the mere language of rights without any corresponding institutions. This may respond to a sense that the constitution needs to look complete and to fit in the global scripts that define the basic formal elements, but without risk of costly constraints. Cheap talk is window dressing.

The term “window dressing” might be taken to imply hiding actual practices from external scrutiny. At the margin, it might be that gullible outsiders believe that the practice is actually implemented. But this is unlikely to be effective as a general matter. Why then do authoritarians put up window dressing? One possibility is that the goal might be not so much to keep outsiders from seeing in, but to keep those inside the country from seeing out.

Dictators may also use the gap between promise and reality to demoralize internal opponents: the false promise is a costly signal of one’s intent to crush opponents. We draw here from an idea developed by Peter Rosendorff in the context of the [UN] Convention Against Torture, in which accession to the convention is accompanied by an increase in the level of torture, at least for certain countries. Rosendorff notes that the accession serves as a costly signal of the intention to repress: the dictator is asserting that he can abuse human rights even with increased costs. One might imagine that this was part of the intention behind Stalin’s famous constitution, which inspired jokes like the one at the outset of this article. Another way in which authoritarian rulers routinely abuse the gap between constitutional promises and actual practice in order to demoralize would-be opponents is by holding elections but manipulating them excessively and blatantly, even when victory is assured.

Indeed, looking at the long history of rights, one observes that authoritarian regimes may be particularly likely to treat constitutions as blueprints. Mexico’s 1917 constitution was particularly innovative with regard to economic and social rights, promising land, education, and labor to the citizenry. These provisions might not have been mere window dressing for a totalitarian party, as might be said of equivalent promises in Stalin’s constitution of 1936, but instead could be understood as aspirations. The land reform promises articulated in the Mexican constitution might be understood as a blueprint that influenced land policy over the decades that followed, during which a large proportion of farmland was redistributed. In short, we see that the same type of provision can be a blueprint in one regime and window dressing in another. This highlights that the particular mix of roles—operating manual, billboard, blueprint, or window dressing—will vary across time and space, and even across different provisions of the same constitution.

Individual provisions within constitutions can play multiple roles. When Hosni Mubarak was confronted with external pressure to liberalize the Egyptian political system in 2005, he modified the article of the constitution dealing with presidential elections. The new scheme was detailed and complex, providing that nominees could only come from political parties that had been in existence for five years and had 5 percent of the seats in each house of parliament. Only Mubarak’s party met the threshold, but other legal parties (which did not include the Muslim Brotherhood) were allowed to nominate candidates for the first election. The provision served as a complex operating manual, laying out a scheme that could be followed to the letter while maintaining Mubarak’s rule. But it also served as window dressing, providing just enough democratic veneer to forestall further U.S. pressure.

FUNDAMENTAL PROBLEMS OF AUTHORITARIAN CONSTITUTIONS—MECHANISMS OF EFFICACY: The study of constitutions in authoritarian regimes must contend with a set of fundamental questions that do not plague democratic constitutions (or do not plague them to the same degree). Our second question is: How do authoritarian constitutions work? More specifically, what is the source of an authoritarian constitution’s force when the authoritarian ruler is above the law and there is no third-party enforcer? When a judicial enforcement apparatus is in place, constitutional provisions evidently make a difference. Because they will be enforced, they raise the costs to certain activities and lower the costs of others. Not so under authoritarian regimes, where enforcement tends to be at the pleasure of the ruler. Therefore, if one is to argue that authoritarian constitutions matter, it is imperative to delve into the basic mechanisms that grant such constitutions force.

We have already suggested various mechanisms underpinning the possibility for authoritarian constitutionalism. One important mechanism is the role of constitutions in coordination, which is closely associated with their function as operating manuals. Coordination is a powerful source of constitutional force. Once a self- enforcing system is in place, deviations are costly to any party, even without a formal apparatus of judicial enforcement.

Another reason authoritarian constitutions have force is that they can, and often do, function as hallowed vessels. The document called “constitution” often enjoys a privileged normative status in the minds of the public, independent of the content of such document. Whether or not judicial enforcement is available, the very idea that a particular proposition is enshrined in the constitution carries normative force in arguments and in behavior. Striking examples of the power of constitutions as hallowed vessels can be found in contemporary dictatorships such as Vietnam and China. Authoritarian constitutions generally call our attention away from the U.S. fetish with judicial enforcement.

A final reason authoritarian constitutions have force is that they can shape social norms and public preferences. As Albert Hirschman put it, “a principal purpose of publicly proclaimed laws and regulations is to stigmatize antisocial behavior and thereby to influence citizens’ values”. A monarchical constitution, for example, could potentially buttress the social acceptability of kingly rule, while a constitution that protects free speech might, over time foster an attitude or norm of tolerance for diversity of opinion. Of course, this need not always be the case—as the idea of constitutions as window dressing suggests, constitutions can also ring hollow to the public, especially when regime practices are sharply at odds with them.

WHY WRITE? PRODUCT AND PROCESS: The final fundamental question with which the study of authoritarian constitutions must grapple is: Why are constitutions written? Several of the arguments that we have offered thus far are excellent explanations of the functions of constitutions understood as sets of rules but are silent about the reasons such rules might be collected in a written document. To underline this point, Myerson refers to such sets of rules among notables as “personal constitutions,” suggesting a distinction from written constitutions. Self-enforcing elite pacts can be informal. Mexican presidents, for example, were for decades chosen by the informal practice of dedazo, whereby the outgoing president would handpick his successor. At the same time, presidential term limits were formally coded in the law. Both term limits and the dedazo were recognized by the Mexican public as the prevailing modus operandi, and both institutions were uniformly and stably applied over a period of time longer than the lifetime of many constitutions in other countries. Nevertheless, term limits were formalized while the dedazo was not.

Why then do authoritarian rulers write or retain a constitution? In addressing this question, it is necessary to draw a distinction between the choice to write a constitution (or to retain a preexisting one), on the one hand, and the constitution’s function, on the other. We have described a range of possible functions or roles played by constitutions. But can we infer the reasons for the adoption of a constitution on the basis of the constitution’s functions? We must at least entertain the possibility that framers might have had as much of a difficult time as contemporary scholars at predicting the downstream effects of adopting a constitution and of particular provisions within it—for one thing, laws, regulations, and formal institutions are known to elicit offsetting behavior. Negretto’s study of constitution making by Latin American militaries illustrates the point. He argues that militaries choose to write constitutions to facilitate their long-term objectives of political, social, and economic transformation and to enhance their influence over post-transition democratic governments. But crucially, militaries are not always successful in these endeavors, and Negretto argues that the key variable is whether they can mobilize partisan support for their institutional innovations.

Why then do authoritarian rulers write or retain a constitution? In addressing this question, it is necessary to draw a distinction between the choice to write a constitution (or to retain a preexisting one), on the one hand, and the constitution’s function, on the other. We have described a range of possible functions or roles played by constitutions. But can we infer the reasons for the adoption of a constitution on the basis of the constitution’s functions? We must at least entertain the possibility that framers might have had as much of a difficult time as contemporary scholars at predicting the downstream effects of adopting a constitution and of particular provisions within it—for one thing, laws, regulations, and formal institutions are known to elicit offsetting behavior. Negretto’s study of constitution making by Latin American militaries illustrates the point. He argues that militaries choose to write constitutions to facilitate their long-term objectives of political, social, and economic transformation and to enhance their influence over post-transition democratic governments. But crucially, militaries are not always successful in these endeavors, and Negretto argues that the key variable is whether they can mobilize partisan support for their institutional innovations.

The point is that dictators, like democrats, do not have perfect foresight as institutional designers. Another possibility is that sometimes the process of writing the constitution serves a political purpose. It allows the regime to be seen as engaged in an important project. This seems consistent with the idea that authoritarians, as compared with leaders in democracies, may be more insulated from social forces in choosing the timing and process of constitution making.

BEYOND SHAMS: THE LESSONS OF AUTHORITARIAN CONSTITUTIONS: We conclude with some thoughts on the lessons of authoritarian constitutions as well as some open questions that beg further inquiry. The lessons can be divided into those for the study of authoritarian regimes and those for the study of constitutions generally.

The first lesson is that rules matter, even when there is a lot of discretion at the top. No single person rules absolutely, and therefore there is a need for intra-elite coordination, as well as for devices to control subordinates. In some circumstances, constitutions serve to meet these functional needs. Furthermore, some authoritarians seek to commit themselves to limit particular courses of action. Tushnet’s, on the normative possibilities of authoritarian constitutionalism, suggest that this is not only possible but also desirable.

Authoritarian constitutions—and the processes of making them—also provide important clues into regime practices. They structure authoritative discourse and provide a political idiom, whether it be of a “socialist market economy” or blessing the family and civil society (as did Chile’s 1980 constitution). By setting the terms of political discourse, constitutions can define what are acceptable as opposed to unacceptable speech acts, legitimating one set and delegitimizing another.

Finally, there is great utility in longitudinal analysis of constitutional sequences in individual countries. As the highest normative act of the state, constitutions mark an exercise of power and create a historical legacy. We observe that constitutions in dictatorships are often replaced or amended by new leaders who come to power. To understand these documents, one needs to read them in light of the predecessor documents, as the sequence of documents will provide clues over the particular leaders’ political concerns and predilections. Constitutions have an “afterlife”. The legacies—of democratic constitutions on authoritarian rulers and of authoritarian constitutions on democratic ones—may shape behavior and idiom long after those who promulgate formal documents are gone.

Tom Ginsburg holds BA, JD, and PhD degrees from the University of California at Berkeley. He currently co-directs the Comparative Constitutions Project, an effort funded by the National Science Foundation to gather and analyze the constitutions of all independent nation-states since 1789.

Tom Ginsburg holds BA, JD, and PhD degrees from the University of California at Berkeley. He currently co-directs the Comparative Constitutions Project, an effort funded by the National Science Foundation to gather and analyze the constitutions of all independent nation-states since 1789.

Alberto Simpser joined the faculty of ITAM (Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México) as Associate Professor in the fall of 2014. He is currently an Associate Member of the University of Chicago’s Center for Latin American Studies. Prof. Simpser holds a PhD degree in political science and an MA degree in economics from Stanford University, and a B.Sc. degree in engineering from Harvard College.

Alberto Simpser joined the faculty of ITAM (Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México) as Associate Professor in the fall of 2014. He is currently an Associate Member of the University of Chicago’s Center for Latin American Studies. Prof. Simpser holds a PhD degree in political science and an MA degree in economics from Stanford University, and a B.Sc. degree in engineering from Harvard College.