PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

WITH FRIENDS LIKE THESE: THE CHINA-RUSSIA AXIS

Richard Weitz: At the recent Russo-Chinese summit in Beijing, both governments again hailed their close ties, signed seventeen agreements on economic and other issues, and vowed to expand their joint military engagements. China pledged to invest more in the Russian Far East and buy more Russian nuclear energy technology. The two countries also declared their identity of views regarding Asia-Pacific security, Iran’s nuclear program, Syria, and other global hot spots. It is hard to contest the regular assertions of Russian and Chinese leaders that relations between Beijing and Moscow are the best they have ever been.

Although sunny assessments about current Sino-Russian ties are correct, such alignments are vulnerable to shifts in the underlying conditions that support them. In the case of Russia and China, these shifting variables include China’s increasing military power, its growing economic penetration of Central Asia, and its impending leadership changes, along with Russia’s political disorders, dependence on a mono-economy of energy, and gloomy demographic prospects. These and other plausible changes could at some point undermine the foundations of their current entente. Interested third parties may or may not be able to shape these variables, but at least other governments need to understand the evolving dynamic of this important relationship and prepare for its future evolution.

Since the Soviet Union’s disintegration in the early 1990s, the two countries have for the most part acted on the basis of shared interests—particularly in maintaining stability in Central Asia, whose energy supplies are vital for both countries’ economic development. China consumes the resources directly, whereas Russian companies earn valuable revenue by reselling Central Asian hydrocarbons in third-party markets, especially in Europe. Both countries know that certain regional events such as further political revolutions or civil wars could adversely affect core security interests. Both governments especially fear ethnic separatism in their border territories supported by Islamic fundamentalist movements in Central Asia.

The shared regional security interests between Beijing and Moscow have meant that the newly independent states of Central Asia—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan—have become a generally unifying element in Chinese-Russian relations. Their overlapping security interests in Central Asia are visible in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Since its founding in 2001, the SCO has essentially functioned as a Chinese-Russian condominium, providing Beijing and Moscow with a convenient multilateral framework to manage their interests in Central Asia.

Chinese diplomatic rhetoric also seeks to put Russians at ease about the growing Chinese commercial presence in the former Soviet space by stressing Beijing’s deference to Moscow on regional security issues. The bilateral defense relationship has evolved in recent years to become more institutionalized and better integrated. As befits two large and powerful neighbors, the senior military leaders of China and Russia now meet frequently in various formats. In addition, the two armed forces engage in many small and several large joint exercises, sometimes along with their Central Asian partners. China and Russia conducted their first official bilateral naval exercise, “Maritime Cooperation 2012,” from April 22 to 27, 2012, in the Yellow Sea near Qingdao.

The two governments coordinate their foreign policies in the United Nations, where they regularly block Western-backed efforts to impose sanctions on anti-Western regimes. Most recently, China and Russia have established a common front in the UN Security Council against Western involvement in Syria. Their leaders share a commitment to a philosophy of state sovereignty (non-interference) and territorial integrity (against separatism). Although they defend national sovereignty by appealing to international law, their opposition also reflects more pragmatic considerations—a shared desire to shield their human rights and civil liberties abuses, and those of their allies, from Western criticism. Chinese and Russian officials refuse to criticize each other’s domestic and foreign policies in public.

Beijing and Moscow oppose American democracy promotion efforts, US missile defense programs, and Washington’s alleged plans to militarize outer space. Chinese and Russian leaders both resent what they perceive as Washington’s proclivity to interfere in their internal affairs as well as their spheres of influence by siding with neighboring countries in their disputes with Beijing and Moscow. Chinese and Russian officials openly call on their US counterparts to stay out of issues that are vital interests for Beijing and Moscow but should, in their view, be of only peripheral concern for the United States, dismissing Washington’s claims to stewardship in upholding universal values, principles of international behavior, freedom of the seas, and a free Internet.

Most Russians do not consider the People’s Republic of China an imminent military threat, and Beijing has prudently avoided provocations that could arouse such concerns in Moscow. Russians generally admire the PRC’s ability to develop its economy so rapidly within the constraints of a single-party political system. Many regret that Russia did not pursue such a path back in the 1990s instead of seeking to align with the West, which they (rightly) believe failed to offer sufficient assistance during Russia’s difficult post-Communist transition and (wrongly) accuse of exploiting Russia’s weaknesses to expand NATO at Moscow’s expense.

With Vladimir Putin in office for a third presidential term, Sino-Russian relations will likely continue improving at a moderate clip. Putin clearly intends to maintain strong relations with Beijing. In one of his pre-election newspaper articles, he said that Russia aimed to catch the wind filling China’s sails.

The Russian government is particularly eager to secure Chinese investment to help modernize the Russian economy. In another article that appeared shortly before his June state visit to China, Putin laid out an ambitious agenda for future Russia-China cooperation, both bilaterally and within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Yet the summit failed to produce the long-awaited natural gas deal between the two countries due to sharp differences over the price China should pay for Russian gas. Even their earlier oil deal, which began delivering Russian oil to the PRC by direct pipeline in 2011, has now become engulfed in litigation and Chinese demands for lower prices. Russian energy firms’ habit of trying to get European and Asian customers to bid against one another might enhance Moscow’s bargaining leverage, but it also creates doubts among the Chinese about Russia’s reliability as a long-term energy partner.

The two governments also remain suspicious about each other’s activities in Central Asia, where their state-controlled firms compete for energy resources. Chinese officials have steadfastly refused to endorse Moscow’s decision to recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which Russia pried from Georgia during the August 2008 war, as independent states. In East Asia, Russia has not supported China’s extensive maritime claims, and has backed Vietnam, a major Russian arms client, in its bilateral dispute with Beijing, which is impeding the offshore operations of Russian energy companies there.

At the societal level, culturally embedded negative stereotypes about the other nationality persist in both counties. Despite years of sustained efforts by both governments to promote cultural exchanges and the study of the other country’s language, ties between Russians and Chinese remain minimal. Their political and commercial elites send their children to schools in Europe and the United States rather than to Beijing and Moscow. The Chinese media criticizes Russian authorities’ failure to ensure the safety and rights of Chinese nationals working in Russia. Russians in turn complain about Chinese pollution spilling into Russian territory and worry that large-scale Chinese immigration into the Russian Far East will result in large swaths of eastern Russia becoming de facto parts of China.

The 2012 SCO summit in Beijing that followed the Russian-China summit confirmed the two countries’ diverging priorities. The economic agenda of the summit, dominated by the Chinese proposal for an SCO development bank, stalled in the face of Russian opposition, as have earlier PRC proposals to establish an SCO-wide free trade zone. With Moscow increasingly wary of China’s economic presence in Central Asia, the two countries are unlikely to come to an agreement on such matters in the near future. Putin’s first visit abroad following his return to the presidency was not to Beijing, but rather to Belarus, followed by trips to France and Germany. The order of these visits is a clear signal of Putin’s geopolitical priorities—to strengthen Moscow’s influence in the former Soviet republics. His Eurasian Union initiative would exclude China from the former Soviet space and erect trade barriers between China and Central Asia. In the security realm, Russia plans to continue transforming the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which excludes China, into Central Asia’s primary multilateral security institution. In East Asia, the Middle East, and other regions, the governments of China and Russia have followed parallel but typically uncoordinated policies.

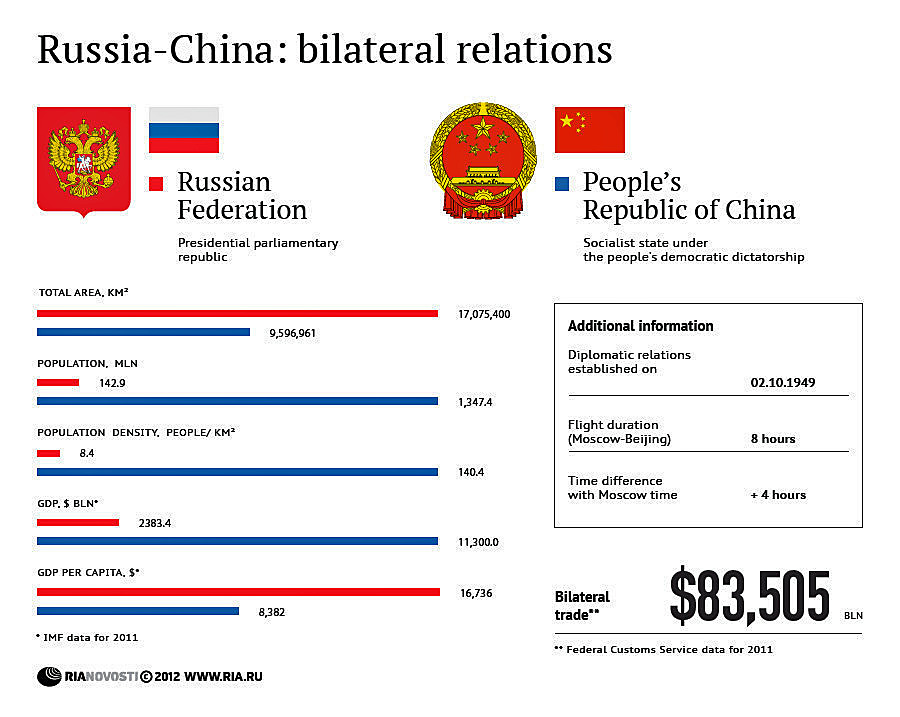

Neither country is the main economic partner of the other. Russians still look to the Europeans, especially Germany, as their standard, while viewing the other former Soviet republics as their main source of imported raw materials. China is also increasing its economic ties with Europe, but the United States still has primacy in Beijing’s commercial calculations. Chinese and Russian business enterprises will need to work extra hard to realize their governments’ ambitious targets for Sino-Russia trade, which is targeted to reach $100 billion by 2015 and $200 billion by 2020. They also will find it hard to address the imbalances in their existing two-way exchanges. China mostly buys Russian raw materials while selling Russians value-added consumer and industrial goods, sometimes made from Russian materials. Russians worry about becoming a natural-resource appendage of the Chinese economic power plant and complain that PRC investors avoid the Russian market in favor of easier opportunities in other countries. Chinese entrepreneurs think that Russia needs to make greater progress in its economic reform program.

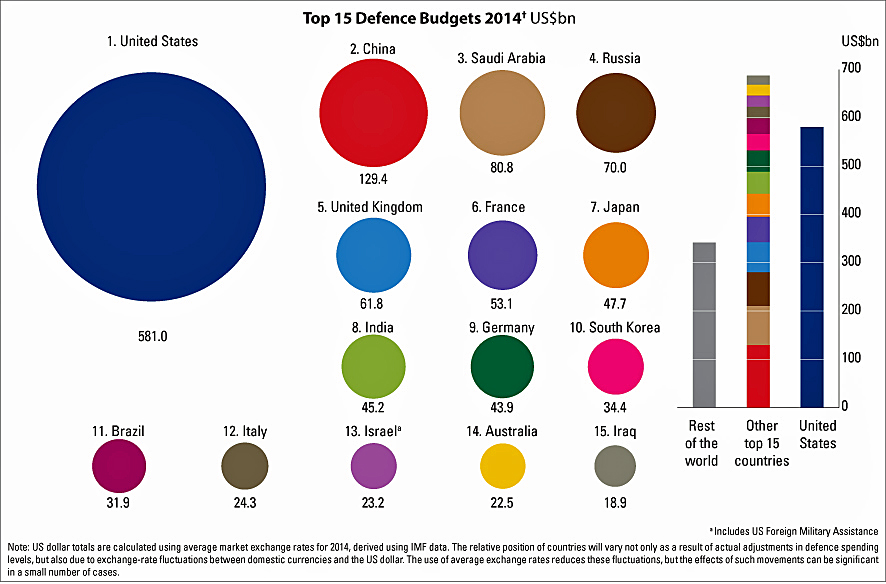

Despite their mutual concern about American strategic ambitions, the governments of China and Russia have not undertaken any widespread collaboration to blunt them. For example, they have not pooled their military resources or expertise to overcome US ballistic missile defense (BMD) systems by, for instance, undertaking joint research and development programs to create shared anti-BMD technologies. Nor have they coordinated pressure against other countries in Europe or Asia to try to force them to abstain from deploying US BMD assets, even in Central Asia or Northeast Asia, regions that border Chinese and Russian territories.

Until recently, Russian defense analysts were confident about maintaining military superiority over China for at least the next decade, but recent displays of growing Chinese defense capabilities, combined with a more confrontational manifestation of Chinese diplomacy, appear to be causing the same unease in Russia as in other countries. Russian arms controllers now openly cite China’s increasing military potential as a reason why China needs to join future rounds of nuclear arms talks. The commander in chief of the Russian Navy, Admiral Vladimir Vysotsky, has also cited Beijing’s interest in the Arctic as a reason to field a larger fleet. The Russian military is also undertaking its own Asian pivot. Although Russian rhetoric is directed against NATO and the United States, Russia’s newest weapons now typically flow to eastern Russia.

The next few years will most likely see a continuation of this mixed pattern of relations between China and Russia, in which they loosely cooperate on a few issues but basically ignore each other regarding most others. But there are several potential developments that could worsen the relationship. Russian resentment could build as China continues to ascend to superpower status, which Moscow once held but has lost. A major Chinese military buildup could also alarm Russians as much as other neighboring countries, who already fear it. Alternately, Russian plans to create an EU-like arrangement among the former Soviet republics could irritate Beijing because such a development could impede China’s economic access to Central Asia. Russian diplomats may soon tire of Beijing’s practice of hiding behind Moscow and relying on Russia to take the heat in blocking Western initiatives regarding Iran, Syria, and other global hot spots. The harmony between Beijing and Moscow in Central Asia arises primarily because the Chinese leadership considers the region of lower strategic priority than Moscow, which still regards it as an area of special Russian influence. This too could change.

A major worsening of China-Russia ties would actually represent a regression to the mean. The modern Chinese-Russian relationship has most often been characterized by bloody wars, imperial conquests, and mutual denunciations. It has only been during the last twenty years, when Russian power had been decapitated by its lost Soviet empire and China has found itself a rising economic—but still militarily weak—power that the two countries have managed to achieve a harmonious balance in their relationship. While China now has the world’s second-largest economy, Russia has the world’s second most powerful military, thanks largely to its vast reserves of nuclear weapons. But China could soon surpass Russia in terms of conventional military. Under these conditions, Moscow could well join other countries bordering China in pursuing a containment strategy designed to balance, though not prevent, China’s rising power.

Heightened China-Russia tensions over border regions are also a possibility. The demographic disparity that exists between the Russian Far East and northern China invariably raises the question of whether Chinese nationals will move northward to exploit the natural riches of under-populated eastern Russia. Border tensions could increase if poorly managed development, combined with pollution, land seizures, and climate change, drive poor Chinese peasants into Russian territory. Russians no longer worry about a potential military clash with China over border issues, but they still fear that the combination of four factors—the declining ethnic Russian population in the Russian Far East, Chinese interest in acquiring greater access to the energy and other natural resources of the region, the growing disparity in the aggregate size of the Chinese and Russian national economies due to China’s higher growth rate, and suspected large-scale illegal Chinese immigration into the Russian Far East—will result in China’s de facto peaceful annexation of large parts of eastern Russia. Although the Russian Federation is the largest country in the world in terms of territory, China has more than nine times as many people.

With the end of the NATO combat role in Afghanistan, an immediate source of tension could be Russian pressure on China to cease its buck-passing and join Russia in assuming the burden of stabilizing that country. Should US power in the Pacific falter, China and Russia might also become natural rivals for the allegiance of the weak states of East Asia looking for a new great-power patron. But for now such prospects linger in the background as Beijing and Moscow savor a far smoother relationship than the one they shared back in the day, when they competed to see which would achieve the one true communism.

Richard Weitz is a senior fellow and director of the Center for Political-Military Affairs at Hudson Institute. He analyzes mid- and long-term national and international political-military issues, including by employing scenario-based planning. His current areas of research include defense reform, counterterrorism, homeland security, and U.S. policies towards Europe, the former Soviet Union, Asia, and the Middle East.

Richard Weitz is a senior fellow and director of the Center for Political-Military Affairs at Hudson Institute. He analyzes mid- and long-term national and international political-military issues, including by employing scenario-based planning. His current areas of research include defense reform, counterterrorism, homeland security, and U.S. policies towards Europe, the former Soviet Union, Asia, and the Middle East.