PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

THE PARABLE OF THE TWO KINGDOMS

Derek J. Mitchell: Periods of close collaboration and bitter rivalry have punctuated relations between China and Russia from the Cold War to the present. On the 57th anniversary of the PRC’s founding, however, President Vladmir Putin of Russia proclaimed his country’s commitment to “confidently developing [relations] in the spirit of strategic partnership and allied relations in the new 21st century.” China proclaimed 2006 the “Year of Russia”; in 2007, Russia celebrates the “Year of China.” And though such initiatives bear the mark of political hyperbole, it is fair to say that China-Russia relations have never been better—though, given the two great powers’ troubled history, the bar was not set very high.

Overall, both China and Russia have sought in recent years to avoid the kind of costly political-military rivalry that overtook them from the 1960s to the 1980s, which led to thousands of troops and weapons systems being deployed in remote and inhospitable areas along their 2,700-mile border. Both countries are focusing priority attention on their respective internal affairs, which leads each to highlight the many areas of converging and complementary interest that may help promote national development—even as they increasingly link arms against the United States—the nation that is most able to thwart their twenty-first-century aims.

What Is the Historical Context for China-Russia Relations? In 1689, China forged its first-ever diplomatic pact with another country as a sovereign equal: the (Qing Dynasty) Treaty of Nerchinsk with Russia. Before that China had viewed external powers as inferiors and refused to acknowledge sovereign equality with other states or peoples. Following its “century of humiliation” from the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries, however, China took a new view toward sovereign equality. The twin Nationalist and Communist revolutions sought to harness China’s national pride, with Mao Tse-tung’s Communist movement becoming particularly allergic to external influence in its affairs by Soviet agents dedicated to asserting their leadership over international communism. Soviet advisers sought to influence Mao’s revolution beginning in the 1920s by promoting a traditional urban-based revolutionary strategy rather than Mao’s rural variant. They also continually pressed the Chinese Communists to reach a political settlement with the Nationalists, including in the immediate aftermath of World War II, which Mao ignored in his successful pursuit of outright victory.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Beijing and Moscow became tense partners, as China found itself isolated internationally and thus forced to rely on Soviet support and assistance. In 1950, they established a formal Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance. The appearance of a Sino-Soviet Communist bloc bedeviled Western strategists during the early stages of the Cold War, as the Soviets, and some Chinese, referred to the relationship as one between “elder brother and younger brother.” Soviet aid brought technological and economic benefits for China throughout most of the 1950s.

Nonetheless, personal, political, and ideological competition between Beijing and Moscow grew as the decade ended. In 1960, the USSR withdrew precipitously its economic aid and refused to assist China’s ambitions to become a nuclear weapons state, reflecting and exacerbating mutual anger and mistrust. An open split between China and the Soviet Union flared during the 1960s, with competition for leadership of international communism, particularly in the Third World.

By the end of the decade, conflict broke out along what had become a tense and heavily militarized border. Although China and Russia averted all-out war, the conflict was a major factor in Mao’s desire for rapprochement with the United States, which led to President Richard Nixon’s opening to China in 1972 and eventual normalization of relations with the United States in 1979.

Sino-Soviet relations remained on military footing into the 1980s. Following the rise of Deng Xiaoping, however, Beijing reevaluated its diplomacy and began pursuing a foreign policy that sought to stabilize China’s foreign relations, reduce its strategic and material costs, and promote its comprehensive national power, with a focus on economic development. China moved away from alignment with the United States to assume a more equidistant posture between Moscow and Washington. Negotiations on border demarcation and demilitarization with the Soviet Union began, albeit in fits and starts. In May 1989, China and Russia normalized relations when Mikhail Gorbachev visited Beijing for the first Sino-Soviet summit in 30 years. The Tiananmen Square crackdown of the following month, which abruptly distanced China from the West, facilitated the rapprochement between China and the Soviet Union, even as the latter faced extinction. In May 1991, for instance, the two governments entered into an agreement on shared borders; the reduction of Russian troops along the Chinese border helped improve the bilateral relationship, as did the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989 and the end of Soviet support for Vietnam’s occupation of Cambodia.

The collapse of the Soviet Union on Christmas 1991 stunned Beijing but did not long derail diplomacy between Moscow and Beijing, which quickly extended recognition to the Russian Federation. Russian policymakers initially leaned toward the West in their orientation and expressed some wariness about the implications of a rising China for their security, but as the decade progressed, Russia’s need to balance its growing disappointment, vulnerability, and reliance on the West led Boris Yeltsin into deeper engagement with Beijing. In 1994, the two governments announced a “constructive partnership.” In 1996, with China and the United States recently embroiled in Taiwan Strait tensions, the two sides upgraded relations to the level of “strategic partnership.” In 1997, agreement was reached on military force reductions, and in November 1998, China and Russia announced that the bilateral border dispute was all but resolved (although it took until 2004 to complete a final arrangement). The institutionalization of cooperation in Central Asia through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the promulgation of a 20-year “Good Neighborly Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation” in July 2001, the first such agreement between China and Russia since 1950, further consolidated Sino-Russian partnership.

What Does China-Russia Cooperation Mean in Practice? Today, China-Russia relations have developed to a point where the two countries focus less on differences than on practical and functional cooperation, including protecting their interests as permanent members of the UN Security Council.

Economics

China-Russia trade and economic links have become a central dimension of the current bilateral relationship. Bilateral trade exploded between 2000 and 2005, growing at more than 30 percent annually, with total trade reaching more than $33 billion in 2006 and Russia maintaining a slight trade surplus of about $2 billion.5 Border trade, which accounts for a third of overall trade, grew to $5.6 billion in 2006, a 33 percent increase over the previous year. China and Russia have announced a goal of overall bilateral trade of $60 billion to $80 billion by 2010, which many observers consider highly achievable given the trajectory of trade relations, particularly given the expanding energy transport ties. In 2005, China became Russia’s fourth-largest trade partner, while Russia became China’s eighth-largest trade partner.

Russia has struggled to diversify its exports to China beyond natural resources, energy, and military arms sales. Six commodities—crude oil, timber, petrochemicals, fish and seafood, potassium fertilizers, and iron ore—account for two-thirds of Russia’s exports to China. In the first six months of 2006, commodities and primarily processed products accounted for more than 90 percent of Russia’s exports to China (against 88.7 percent in 2005 and 84.2 percent in 2004). Rising oil prices alone have made up a considerable part of Russia’s absolute increase in export value to China. China, meanwhile, has increased its exports to Russia in a range of manufactured and high-tech goods—mostly leather products, footwear, and machinery—to complement the basic textile and low value-added items that traditionally formed the mainstay of its trade.

Overall, the bilateral trade relationship is marginally more important to Russia than to China. China’s trade with Russia accounts for 2 percent of its total trade and is a small fraction of its $300-billion trade with the United States and $200-billion trade with the European Union. Likewise, Russia’s trade with China accounts for only 6 percent of its total trade. Even the most optimistic projections of the two countries do not anticipate a significant narrowing of this gap in relative trade value compared with the developed West.

By the end of 2006, Chinese investment in Russia involved 657 projects worth approximately $1 billion, while Russian investment in China totaled $1.4 billion. Most of the investment has been related to their bilateral trade: China’s investment has been in the natural resource, agriculture, consumer appliance, wood processing, microelectronics, and telecommunication sectors; Russia has invested in nuclear power, construction, chemicals, agricultural machinery, and automobiles. Most investment occurs near their common border. China has announced a goal to increase investment in Russia to $12 billion by 2010 (an ambitious target that may go unmet). There have been initiatives to increase cooperation in the science and technology sector as well, most notably in defense (see below).

Energy

Unabated growth in China’s domestic demand for oil has forced Beijing to regard securing stable energy sources as a primary foreign policy goal. Russia, as the world’s largest supplier of oil and natural gas, makes for an obvious source. As China has sought to diversify its energy sources away from the volatile Middle East and vulnerable sea transport lanes, it has turned to Russia and the oil-producing nations of Central, South, and Southeast Asia for secure energy supplies that may be transported over land. Oil shipments from Russia have in fact relied largely on rail transport to date.

Oil, oil products, coal, and electricity amounted to 40 percent of Russian exports to China in 2005, a figure that is estimated to rise to around 60 percent in 2006. Russia is currently China’s fourth-largest oil provider after Angola, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. In 2005, China imported more than 12 million tons of crude oil from Russia, accounting for more than 10 percent of China’s oil needs.

This percentage is sure to change in Russia’s direction in coming years. Russian and Chinese oil and gas companies have formed joint ventures for exploration and production of energy assets within Russia and abroad. During Russian president Putin’s visit to China in 2006, the China Natural Petroleum Corporation (CNPC or Sinopec) and Russia’s Gazprom signed a memorandum of understanding whereby Russia vowed over time to supply 60 billion to 80 billion cubic meters of gas to China annually, with resources beginning to flow in 2011. Sinopec and Transneft have signed an $11.5-billion deal for the construction of the East Siberia–Pacific Ocean oil pipeline. Sinopec has also signed a long-term oil and natural gas investment and cooperation agreement with Rosneft.

Nonetheless, Moscow has annoyed Beijing with its indecision and gamesmanship after a decade of negotiations with both Japan and China over the terminus of a major eastbound energy pipeline. Moscow wavers over whether the route ought to go to Daqing in China or to the Pacific port of Nakhodka, which would serve the Japanese and international markets. Russia has repeatedly reassured China that agreement for a pipeline to Daqing is imminent; nonetheless, implementation remains elusive. While most observers expect that at least a branch of the oil pipeline will run to Daqing, Chinese observers worry that Russia’s tactics may bode ill for the reliability of Russian supply and future China-Russia energy deals.

Russia has proceeded gingerly in entering long-term energy arrangements with China for fear of spurning Japan, another prospective major customer and because of concerns about losing its leverage to a monopoly customer as large as China. Nonetheless, Russia recognizes China will be its largest long-term market. The core obstacle remains the lack of transportation and production infrastructure. While several oil and natural gas pipelines to China are being planned or under construction, with product slated to begin flowing across the border by 2010, observers question whether Russia will indeed have the production and transport capacity to meet its oil and natural gas delivery targets outlined in its agreements with China.

In addition, while the two countries will assuredly enter into a higher degree of energy sector interdependence in coming decades, the Siberian pipeline issue demonstrates that the future of the bilateral energy partnership will be driven by cold calculations of economic self-interest and a degree of strategic wariness, rather than any pretensions of strategic partnership.10

United Nations

More broadly, Chinese and Russian senior officials regularly coordinate their approaches to key foreign policy matters and cooperate on foreign and military intelligence gathering. China and Russia have aligned themselves in the UN Security Council, joining forces on issues such as the war in Iraq, Iran, Sudan (Darfur), North Korea, and Burma, often in opposition to the U.S. position. In particular, both countries have sought to prevent the use of punitive sanctions as a tool of international diplomacy, contending that external pressure will fail to achieve objectives better than concentrated good faith diplomacy.

The two countries are also leery of sanctions, given their vulnerability to pressure for their own transgressions on issues such as human rights and also their concern about losing economic interests in sanctioned countries. On many occasions, they have worked together to oppose or water down Security Council resolutions that include sanctions provisions, including those concerning Iran and North Korea. In January 2007, China and Russia cast their first joint veto since 1972 against a U.S.-sponsored resolution condemning Burma’s brutal military junta. China does not like to stand alone to oppose a Security Council resolution; China-Russia joint vetoes may become more frequent in the future.

To What Degree Is China-Russia Rapprochement Directed at the United States? China and Russia have never explicitly admitted a joint agenda to constrain U.S. power. Nonetheless, it is clear their bilateral relations have grown deeper and more strategic as U.S. political and military activism has increased and their respective trust in the United States has declined.

The China-Russia strategic partnership agreement explicitly states that it is “not directed at any third country.” This statement is consistent with China’s “new security concept,” which offers an alternative vision for post–Cold War international security to the U.S. alliance-centered structures that remain in East Asia and Europe.11 Both China and Russia have felt that they are the unspoken threat against which these regional alliances are directed. The China-Russia strategic partnership was intended to serve as a model for the alternative structure.

The bilateral partnership was also meant to be an unspoken indictment of unwelcome U.S. intervention in their respective internal affairs, whether human rights generally or separatist movements more specifically—Chechnya in the case of Russia; Taiwan, Tibet, and Xinjiang in the case of China. Increasing domestic vulnerability, matched with an acute awareness of the populist “color revolutions” that led to democratic reforms and greater protection of civil rights in several countries of the former Soviet Union, led both China and Russia to restrict the operation on their territory of U.S. and other international nongovernmental political development organizations in recent years. Russia and China are particularly suspicious about U.S. intentions in this regard.

During the 1990s, Russia also resented U.S. military incursions into its former sphere of influence in the former Yugoslavia, as well as U.S. political and economic inroads into former Soviet territory, including NATO’s expansion into the Baltics. During a 1995 meeting, Jiang Zemin and Russia’s foreign minister declared joint opposition to hegemonism, a codeword for the United States (and ironically a term applied by China to connote the Soviet Union during the Cold War). China drew analogies between assertive U.S. military involvement in the former Yugoslavia and potential U.S. intervention in Taiwan and thus found common cause with Russia in opposition to U.S. actions. The 1996 Taiwan Strait crisis, during which the United States sent two aircraft carriers toward the strait, and the accidental U.S. bombing of China’s embassy in Belgrade (Serbia), only heightened Chinese suspicions about U.S. intent.

In 2000, both countries announced their opposition to U.S. missile defense plans and specifically to unilateral U.S. revision of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. While asserting their desire to uphold the principle of “strategic stability,” China and Russia were undoubtedly influenced by the effect missile defense would have on the continued growth of U.S. military power and on U.S. willingness to impose itself abroad as a result.

Since 2001, U.S. international assertiveness has only tightened Chinese and Russian strategic alignment, despite the occasional setback. In working together, each side is hedging against the potential application of U.S. power against its interests, making the basic power calculation that they are stronger together than apart and that their leverage is greater when joined in a common diplomatic approach than it is when they act to protect their interests separately.

Thus, while China and Russia both attach great importance to their bilateral economic and political relationship with Washington, and recognize they must avoid fundamentally alienating the United States even as they attempt to counterbalance U.S. influence, U.S. actions will remain the most important factor in determining the future direction and intensity of the strategic partnership in coming years.

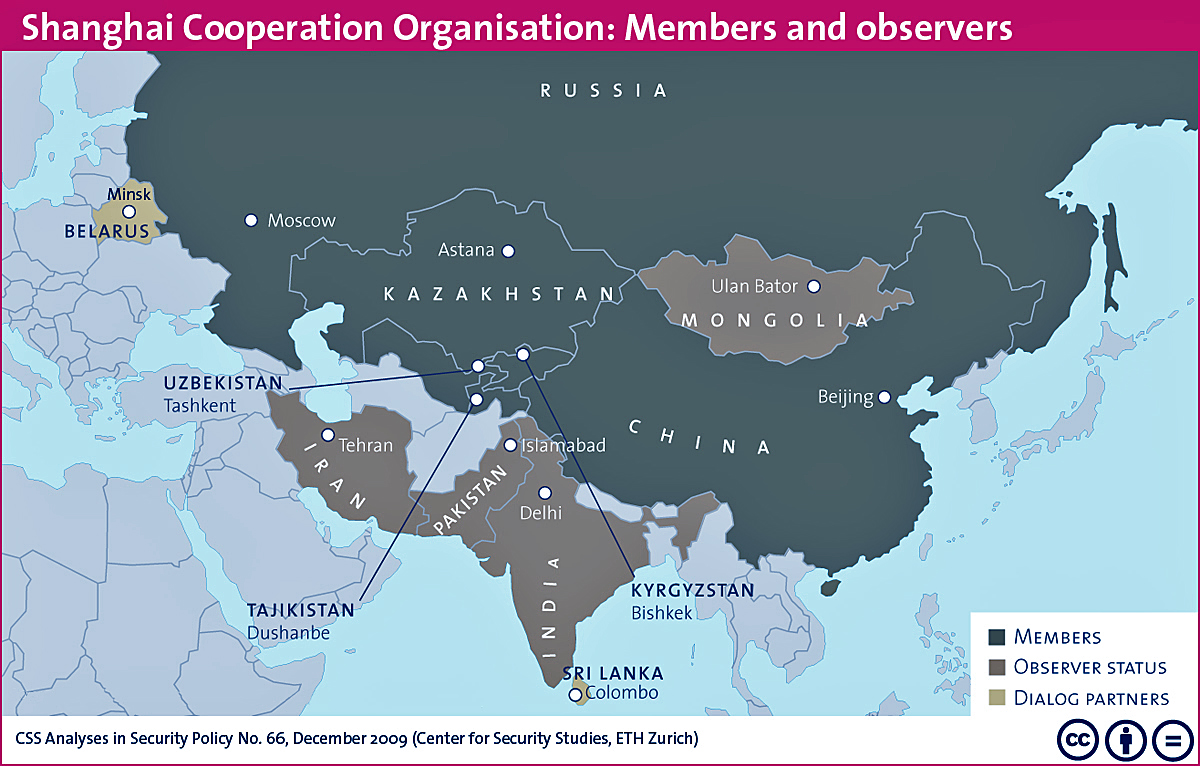

Is the Shanghai Cooperation Organization the Foundation of a Regional Strategic Alliance against the United States? The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is very unlikely to become an alliance against the United States, but it is an increasingly substantial vehicle for cooperation and coordination of interests among the six constituent powers, including China and Russia, that could be applied to limit U.S. power and influence in Central and South Asia in the future.

In the mid-1990s, military confidence building and border delimitation became the initial focus of regional cooperation among China, Russia, and the Central Asian nations of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. The five nations dubbed themselves the “Shanghai Five,” after the location of their first formal meeting in 1996, and committed themselves to address the “three evils” of “terrorism, extremism, and separatism.”

In June 2001, the Shanghai Five added Uzbekistan to their membership and changed their name to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The group has since added India, Pakistan, Mongolia, and Iran as observers. Since 2001, the SCO has developed more rapidly than expected and has begun to institutionalize itself by establishing a secretariat in Beijing and a Counter-Terrorism Center in Tashkent, as well as developing other functional cooperative mechanisms to promote regional integration.

Concern over cross-border support for regional terrorist or separatist networks remains a core aspect of the SCO’s work, although the group has increased its border administration cooperation to address transnational crime, narcotics trafficking, environmental monitoring, migration, transportation corridors, infrastructure development, and border trade management. The SCO has also expanded its scope to include discussion of security issues beyond immediate cross-border challenges. U.S. moves into Central Asia to support post-9/11 combat and counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan threatened at first to overshadow the SCO but eventually spurred the organization to accelerate its institutional development. China-Russia coordination on Central Asia policy grew as they strove to protect their interests along another vulnerable flank. They found common cause in minimizing U.S. military and intelligence presence in the region and ensuring that their periphery is secure from the prospect of a U.S.-led military bloc next door.

Central Asian nations also have seen the value of preserving a hedge against undue U.S. influence in their affairs and sending a signal to the United States that they have strategic options. Indeed, following U.S. condemnation of a violent crackdown on demonstrators in the Uzbek city of Andijan, the SCO served as a convenient vehicle to demand a timetable for the withdrawal of the U.S. military presence from Central Asia. At the same time, Central Asian nations also view the SCO as a way to maintain leverage in their relations with their huge neighbors.

In Central Asia, China and Russia are engaged in a complex mix of cooperation and competition. China’s economic expansion, appetite for energy and natural resources, and desire to address cross-border challenges to social and political stability in its northwest province of Xinjiang have led Beijing to focus increasingly on Central Asia as a strategic interest. At the same time, Russia considers Central Asia its traditional sphere of influence. China’s desire to make political, economic and energy inroads into the region has remained difficult to reconcile with Russia’s desire to preserve a controlling stake in the region’s energy system and infrastructure and maintain a strategic buffer along its eastern periphery. China has gained influence in Central Asia at Russia’s expense, a development about which Russia remains wary. Indeed, Russia’s interest in the SCO includes keeping an eye on, channeling, and diluting growing Chinese influence in the region, highlighting a continued if latent rivalry that shadows the relationship.

Russia in fact has viewed the SCO as fundamentally a Chinese venture, reflected in the title itself. Moscow would prefer to deal with Central Asian security through the Collective Security Treaty Organization, where Russia holds hegemonic sway—and China is absent. Nonetheless, Russia has recognized the reality of growing Chinese influence and decided to focus on accentuating cooperative rather than competitive aspects of their regional interaction.

China and Russia have explicitly rejected the notion of turning the SCO into a military alliance akin to NATO, as some extreme hardliners in Russia would prefer. Russian defense minister Sergei Ivanov has stated publicly that “We are not going to form any ‘anti-NATO’ bloc in the East. The time of military blocs and camps has gone.” Likewise, China knows its reputation would suffer if it violated its precept against the formation of military alliances. In its current form, the SCO serves China well for promoting its interests in Central Asia, reassuring nations on its western periphery, including Russia, of its benign intent and promoting the creation of a multipolar world. More security, including military, cooperation among member states is likely in coming years for both confidence-building reasons and as a general component of their coordination of responses to common challenges.

Is China-Russia Military Cooperation Fundamentally Altering the Balance of Power in East Asia? Following the 1989 arms embargo by the United States and Europe in the wake of Tiananmen Square, Russia became China’s primary advanced weapons systems supplier. Endowed with the USSR’s military-industrial heritage, but hobbled by the lack of a healthy domestic market, Russia needed Chinese customers to keep its weapons industry afloat as much as China needed Russian hardware to fuel its military modernization. The relationship thus was one of natural and complementary interest. In the process, the arms trade relationship has enabled China to rapidly develop its military capabilities over the past decade, which accelerated following the 1996 Taiwan Strait crisis and U.S. intervention in Kosovo in 1999.

Since 1992, China has purchased more weapons from Russia than from all other countries combined.18 Between 1989 and 2005, Russia exported more than $20 billion worth of conventional armaments to China (at constant 1990 prices), accounting for more then 90 percent of China’s arms imports during this period. Between 1995 and 2005, Russia’s arms sales to China accounted for approximately 37 percent of its total arms exports.20 Since 1991, more than 1,000 Russian military experts have been involved in technical exchanges with China.

Arms sales to China have been a complicated matter for many Russian strategists, who worry that the economic benefits come at the strategic cost of facilitating the military modernization of its mammoth and ever-more-powerful neighbor. Moscow has been careful not to sell the most advanced versions of its weapons systems to China, although Beijing continues to push the boundaries of what Russia will offer in technology and platforms. Russian deal makers have tended to transfer air and naval capabilities rather than ground platforms, which might challenge Russian strategic interests along its rather vulnerable eastern periphery.

Nonetheless, over the past 15 years, the level of hardware and technology transfer between Russia and China has been substantial. The weapons systems and technology that China has procured from Russia include Kilo-class diesel submarines; Su-27 and Su-30 fighter planes; Sovremenny-class destroyers equipped with antiaircraft carrier cruise missiles; AA-10 and AA-11 air-to-air missiles; SA-10, -15, and -20 surface-to-air missiles; and advanced aircraft radars. China benefited from Russian (and Israeli) technological assistance for the successful, if belated, deployment of the advanced indigenous J-10 fighter in early 2007.

China and Russia have an increasingly robust program of space cooperation. China’s manned Shenzhou program is based on Russian Soyuz technology, although China has added its own indigenous components. The two countries also work together in lunar research, manufacture of communications satellites and scientific equipment for remote earth sensing, and processing of satellite information. China is on the cusp of participating in Russia’s GLONASS (global navigation satellite system) program. The two countries plan to establish two space laboratories and even cooperate on a mission to Mars.22

Russia’s cooperation with China in space-related technology, including rocket and satellite programs, became of particular concern to the United States and others after China’s successful test in January 2007 of an antisatellite weapon against one of its aged weather satellites. Chinese space capabilities are an apparent effort to negate U.S. military power given the United States’ increasing reliance on high-tech command and control, navigation, surveillance, and guidance systems for its advanced missile systems and transformational battlefield capabilities. Vladimir Putin avoided criticizing China publicly for the test, instead taking the opportunity to refer obliquely to U.S. antisatellite efforts and to affirm Russia’s opposition to militarization of space. While Moscow likely appreciated the demonstration of potential U.S. military vulnerability, China’s test may also have given pause to Russian security hands, who will note yet another example of China’s great leap ahead in military affairs and comprehensive national power more generally, which may come to threaten Russian security interests.

In October 2005, China and Russia staged Peace Mission 2005, their first joint/combined military exercise. Held under the aegis of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the exercise involved a total of about 10,000 participants on both sides and was framed as an exercise to combat “terrorism, extremism, and separatism.” Nonetheless, the considerable conventional air, sea, and ground power, which included a major Chinese-led amphibious operation, along its eastern shore far from the SCO’s terrestrial base, bore remarkable resemblance to a Taiwan scenario. Although the exercise proved more an opportunity for Russia to show off its military hardware to a prospective client than a real indication of the beginnings of a military alliance, the two countries clearly sought to send a message to the international community, and particularly the United States, about the development of China-Russia strategic relations. Another joint/combined military exercise, entitled “Peace Mission–Rubezh 2007,” is planned for this year, although its exact nature and territorial scope remains unclear.

It is extremely unlikely, however, that either country would come to the other’s aid during a military crisis, for instance during a Taiwan situation or escalation of unrest in Chechnya. The relationship does not nearly rise to that level of political or military partnership;25 indeed, their July 2001 treaty, unlike the 1950 version at the start of the Cold War, contains no security guarantees, and Russian defense minister Sergei Ivanov has seen it fit to state publicly that “No military-political obligations bind Russia and China.”

Russia’s defense relationship with China, including arms sales, is expected to continue in coming years. There is growing evidence, however, that the military relationship might sour, particularly in the area of arms sales. Russian technical cooperation and Chinese skill at reverse engineering have led to a growing indigenous capability for China to meet its defense needs, leading to a declining interest in purchases from Russia.27 Russia’s defense industry is becoming frustrated and worried about this development, which could contribute to broader suspicions and friction between the two countries over time.

Nonetheless, the 1990s-era debate among Russia’s elite about a potential strategic threat from China has receded during the Putin years in favor of a consensus on partnership, and there is currently little evidence that Russia’s perspective toward China will change after President Putin leaves office in 2008. China’s military development with Russian assistance has complicated U.S. contingency planning in East Asia and challenges the balance of power across the Taiwan Strait. Its overall trajectory is heightening concern in Washington, Tokyo, Seoul, and elsewhere regarding the regional balance of power over time, and tilling the soil for an arms race—particularly in the absence of greater transparency.

How Are Social and Cultural Elements Affecting China-Russia Relations? Despite partnership on a growing range of issues, China-Russia relations continue to labor under some fundamental social and cultural constraints. The legacy of history weighs heavily on the two countries, which retain a residue of official and popular mistrust. Trends in relative power lean toward China, a new reality that does not sit well with many Russians. Even as Russia resisted becoming a junior partner of the United States after the Cold War, it resents even more the prospect of playing the role of junior partner to China.

The stark cross-border demographic imbalance—there are fewer than 10 million inhabitants in the Russian Far East and more than 150 million in China’s northeast—continues to haunt cross-border relations. Chinese economic, social, and demographic encroachment into the region, even as Russians are moving westward, creates concern about the future of Chinese influence on Russia’s territorial periphery and thus strategic concerns about China overall. Xenophobic outrage against Chinese migration into the Russian Far East, and against final border demarcation in 2004, which some Russians claimed resulted in a net territorial gain for China, has moderated somewhat in recent years as local populations accommodate to the new realities, and the demagogic local governor behind much anti-Chinese sentiment in the region, Evgenii Nazdratenko, was shuffled to a faraway political post.28

Nonetheless, the significant and growing demographic imbalance remains a potential source of Russian fear and xenophobic nationalism against China. While Russia strategists downplay the likelihood of military conflict with China, they cannot dismiss the prospect of a more powerful, assertive, and technologically sophisticated China willing to use economic, demographic, and military muscle to overwhelm its demilitarized and demographically challenged northern flank.

Indeed, the two countries remain deeply mistrustful of, if not alienated from, each other at a popular level. In a 2006 poll conducted by Russia’s Public Opinion Fund, fewer than half of Russians surveyed viewed China as friendly toward Russia, while 30 percent saw China as an unfriendly nation, a steep drop from just four years before. From an economic standpoint, a July 2005 survey found that 62 percent of Russians view China’s increasing presence negatively, while 66 percent considered the involvement of Chinese companies and workers in the mineral industry in Siberia and the Russian Far East as dangerous for Russian interests.

Few social or cultural ties of any depth exist between the broader Chinese and Russian peoples, despite efforts by both sides in recent years (including announcing the Years of Russia and China). In the end, both populations remain more focused on building ties with the West than with each other.

At an anecdotal level, Chinese who have visited Russia express disgust with the undercurrent of racism and violence they often experience in the country. At the elite level, Russia’s gamesmanship concerning the on-again/off-again oil and gas pipeline to China has frustrated the energy-hungry Chinese and reminded them not to rely too readily on Russian good will for its development. China’s poor handling of the Songhua River chemical spill, in late 2005, infuriated Russians, who remained suspicious about Chinese lack of transparency and good-faith concern for the cross-border effects of its policies.32 Putin’s acquiescence in the establishment of U.S. bases in Central Asia adjacent to China (and Afghanistan) after 9/11, and Russia’s apparent accommodation of NATO and U.S. missile defense in 2002, stunned and angered Beijing, which felt undercut after several years of “principled” partnership with Russia in opposition to U.S. foreign basing, alliances, and military development. Although the relationship soon recovered, thanks in large part to heavy-handed and uncompromising U.S. foreign policy in the years that followed, these incidents served as an unpleasant reminder about the uncertainties of Russian fealty to principle and partnership with China.

As China and Russia reach more agreements on a range of energy, trade, defense, and economic matters, and as mutual expectations increase, failures on the part of either country to follow through on deals or to achieve shared goals could tap into mutual mistrust. Yet, given their shared interest in prioritizing domestic challenges, promoting their great power status, and protecting themselves against growing U.S. influence, it is unlikely that political support for the relationship will flag on either side in the near term. The result will be a complex relationship, rooted in a history of rivalry but geared toward multiple areas of mutual and complementary interest that will continue to challenge U.S. foreign policy and global influence for years to come.

Derek James Mitchell (born September 16, 1964) is an American diplomat with extensive experience in Asia policy. He was recently appointed by President Barack Obama as the first Special Representative and Policy Coordinator for Burma with Rank of Ambassador, and was sworn in by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on October 2, 2011. On June 29, 2012, the U.S. Senate confirmed him as the new United States Ambassador to Burma.

Derek James Mitchell (born September 16, 1964) is an American diplomat with extensive experience in Asia policy. He was recently appointed by President Barack Obama as the first Special Representative and Policy Coordinator for Burma with Rank of Ambassador, and was sworn in by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on October 2, 2011. On June 29, 2012, the U.S. Senate confirmed him as the new United States Ambassador to Burma.