PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Government and the process of governance in Africa

Joy Alemazung

Government, Governance and Power: Government can be defined as the body of officials and institutions constituting the leadership authority of a state. Depending upon the type of political system, say, federal or centralized state system, and upon the political organization and distribution of powers of each state, government may exist at different levels beginning with local government and ending with the highest authority of the state—the national executive branch headed by the head of state or government. However, the executive branch is the irreducible core of government with its existence dating as far back as before the times when the idea of separation of powers started filtering into the political thinking of the state—government has been a universal phenomenon since ancient times through absolute monarchs to present date.

Considering its executive function, a government is a governing body or organ entailing offices, functions and authority. In this regard, the government can include the ruling political party or, in the case of a parliamentary system of government, a coalition of political parties and its chosen cabinet of ministers.

Considering its executive function, a government is a governing body or organ entailing offices, functions and authority. In this regard, the government can include the ruling political party or, in the case of a parliamentary system of government, a coalition of political parties and its chosen cabinet of ministers.

The widespread use of the term governance has triggered research and political debates trying to understand what it entails. The increase in complexity of political processes that draw in new and more political actors into political activities, has led to an emancipation from the traditional thought about government as the sole organization, machinery or agency endowed with the exercise of authority and performing administrative functions of the state.

The notion of governance, defined as the exercise of authority (legitimate political power) or control, or “the process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented), is as old as human civilization itself”. This exercise of authority or decision-making processes and their (non) implementation are at the core of Africa’s major state and political problems, according to the World Bank.

Governance or the exercise of authority often “unfolded” poorly as a result of irresponsible, non-accountable and selfish tyrant leadership. At times, it resulted in economic set-backs and subsequent poverty and societal devastation in the presence of abundant resources. Michael Ross maintains that conflicts arise in poor countries (especially Africa) due to a complex set of events, which include poverty, ethnic or religious grievances and unstable governments.

Building and sustaining a well-governed state requires responsible leaders accountable to the people. It requires leadership characterized by a level of statesmanship and it needs a social contract formed by a committed government.

Power in a general sense is the capability to intervene in a given set of events to alter them. Anthony Giddens terms this the transformative capacity. In democratic governance, the leader or the government exercise the measure of power they receive from the people to govern in the name of the people. This power is granted to the governor based on trust that the state will represent and fight for their common interest. But these governance processes involve not only the legitimate power from the people but also applying state resources to instigate processes to distribute goods fairly to the people.

Resources at the governments’ disposal are therefore directly related to power because “governors” need to employ them in the course of their activities in order to accomplish the nation’s goals, meet their ends (serve the people) or implement policies. Giddens classifies resources in terms of power into two categories, namely: allocative resources which mean dominion/control over material facilities, natural resources and forces that may be harnessed in their production, and authoritative resources, meaning dominion over activities of human beings/resources themselves. Governments have to pursue diverging goals to provide for its citizens with the ambition of preserving the life, liberty and property of its people.

Summing up all the actors, processes and mechanisms involved in governing a country, including the institutional components like the separation and distribution of powers, governance can be described as the exercise of authority by the governing body such that institutions (private and public as well as formal and informal arrangements) and individuals (private and public) are incorporated in the management of nation-state, whereby the goal is the well-being of the majority if not all of the people. It follows that governance is a continual process, which accommodates and cooperates between conflicting and diverse interests for the advancement and preservation of the people/society.

Thus, governance is a term that denotes the relationship existing between the body of government, with its policy-making and implementation activities, and the general public. The continual political processes of governance cover different areas including the political, the administrative, and the economic and socio-cultural components of the state, which are necessary to assure the common good and preservation of the society. A good government is, therefore, one that ensures good governance processes, makes and implements policies that are defined by the expectation of the people, distributes power, rules by the law and follows up and verifies performances of all the actors involved in the governance process while promoting their improvement and preventing undesirable circumstances.

The absence of this kind of governance and the vast numbers of undesirable circumstances in African states for example in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Zimbabwe, Sudan and Equatorial Guinea (all countries very rich in natural resources but occupying the last position on the Mo Ibrahim African Governance Index). The poor management of the state or bad governance in these countries account for undesirable circumstances like incessant conflicts and poverty in leading to a cry for good governance (see 2014 Ibrahim Index Country Ranking of 52 African Countries based on Indicators: sustainable economic opportunity, human development, safety and rule of law, and participation and human rights: DRC rank 47/52, Zimbabwe rank 46/52, Eritrea rank 50/52, Somalia rank 52/52).

Good governance is not equal to democracy: Due to the manner in which democracy and good governance are packaged together and presented to Africa, one might be tempted to overlook the dichotomy that exists between the two concepts. Democracy is the rule of the citizen body or the people, stemming from the Greek word demos, meaning the “citizen body”, and cracy, meaning “the rule of”. The people are the central actors, deciding through their votes who or which party or group will represent them. The people, therefore, delegate decisions on their behalf and hold the leaders accountable that oversee the administration, implementing the policies.

Despite the existence of varying definitions for democracy whether one follows a Weberian or Schumpeterian Model, characterized by elitists and competitive elements, or a Dahlian Model with focus on broad participation besides the normative standard of democracy like human rights and power limitation, some generally accepted minimum values must be maintained for one to speak of democracy. Robert Dahl presents five basic criteria that a democracy should meet:

(1) effective participation from the citizen,

(2) voting equality during elections and for all who have attained the voting age,

(3) enlightened understanding so they are well-informed to make the best choice that serve their interest,

(4) control of the agenda, that is, citizens must be able to decide about political matters that need deliberation,

(5) and inclusiveness, which implies inclusiveness of all citizens of the state in the political process.

Joseph Schumpeter defines democracy in terms of “the will of the people” and the “common good.” Schumpeter divides democracy into two parts: the will of the people as the “source of democracy” and the common good as the “purpose” of democracy. Leaning on this definition, it implies that a system cannot qualify itself as democratic unless the will of the people prevails and there is a reliable, efficient and effective “mechanism” (election) through which the people can manifest their will. The people are the central actors in the process.

Therefore, the ability of the people to participate freely in such decision-making processes is essential in a democratic system. Competitive elections in democracy are the central selection procedure of leaders by the people they govern. Such elections which are periodic in democracies and must be free and fair are the only mechanism for translating the consent of the governed, that is, the people, into governmental authority. Thus democracy does not only offer the people the opportunity to translate their consent to governmental authority, but also the attainability to limit or put an end to it in subsequent elections. This “limiting” component of democracy through elections or constitutionalism is very important in sanctioning bad rulers/governments.

Good governance and democracy—what is their relationship? Based on the understanding of democracy and democratic principles, we will unpack the interlinkages between governance and democracy. Governance is the exercise of authority by the governing body such that institutions (private and public as well as formal and informal arrangement) and individuals (private and public) are incorporated in the management of state. The goal is the well-being of the majority if not all of the people. Thus good governance in its simplest form therefore means positive government performance—that is, performance in managing the economy, responding to the people’s needs, mobilizing state resources (material and human; private and public), assuring social justice, providing peace and security and promoting a favorable environment for individual pursuit.

These performances can also be attained even by a (benevolent) dictator or an authoritarian leader who may detest opposition or objection to his rule. However, a dictator would have to ignore his personal needs and put the general interest of the nation on the top of his policy agenda, only then could he meet these aforementioned performances to a meaningful extent. On the other hand, a democratically elected government may not serve the interest of the people. After winning the elections the governors may choose to do what favors them. They could have a backdrop of business people as their supporters or own a business themselves; they could choose to implement company suited capitalistic policies unfavorable to the majority of citizens in their countries, leading to increased poverty and the unhappiness of the majority.

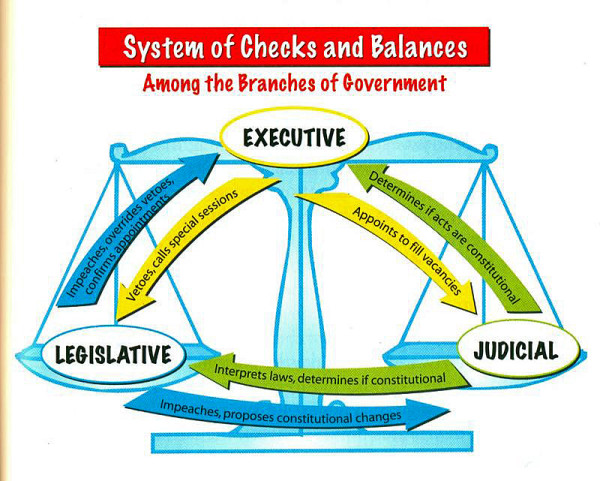

However, it must be kept in mind that in true democracies where democratic institutions and practices are effective, bad governance is limited compared to autocratic systems by accountability to citizens. Unlike in an authoritarian system where the people have no constitutional and procedural means of sanctioning the autocrat, this situation is taken care of in democracy through elections and checks and balances of interest representation. The rule of law regulates the fair and equal treatment of all citizens. Thus, good governance and democracy are complementary and necessary for free and successful functioning states. While democracy in the presence of a bad governor may not be able to guarantee good governance, he/she is most likely not re-elected.

Bad government, governance crisis and the introduction to Good Governance: Many states in Africa experienced independence in the midst of nationalist political pluralism. After independence, many of these states saw political pluralism undermined or prevented by the same freedom fighters that gave them independence. Post-independent Africa was furthermore characterized by inexperience in proper state management and poor governance. Indicators are disadvantageous economic policies, failure to diversify the economy and promote the agricultural sector, which is a key sector for a large number of African countries. Kevin Shillington presents this for the case of Zambia after its independence with Kenneth Kaunda as president:

“With soaring copper prices from the 1950s through 1970, Zambia at independence had huge reserves of foreign exchange. But this was at the expense of an over-reliance upon the single industry of copper mining. Copper accounted for 92 per cent of foreign earnings and 53 per cent of total government income. Zambia spent lavishly upon free education and health and a whole range of prestige urban building projects. But there was little effort to diversify the economy and no effective investment in peasant food cultivation… The civil service boomed and the rapid expansion of non-technical education drained people away from life in the rural areas. Almost without realizing it, Zambia – a huge, formerly self-sufficient, agricultural country with low population – quickly became a net importer of food”

Poor management of the state post-independence set many resource-rich countries in Africa on the wrong track. During this period Kenneth Kaunda’s counterparts in other countries including Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, Idi Amin of Uganda, Jean Bedel Bokassa of Central African Republic to name a few, abused human rights, abused power and ignored the common good, trading it for a “political unity” that according to them was necessary for the development of the new states. These were very strong indications of failure and state destruction, yet it was only a World Bank report as late as 1989 that shed attention on “weak governance” as a major cause of Africa’s underdevelopment, negative economic output and devastating poverty. Until this time the international community had contented itself with so-called stable regimes collaborating with tyrants and autocrats and, thereby, trading the freedom and long term well-being of the African people for “stability”.

In addition, William Easterly outlines the support African tyrant rulers received from Western countries by “sponsoring native autocrats” in Africa, arguing that foreign aid is a transfer of wealth “from being spent by the best government in the world to being spent by the worst”. International institutions like the World Bank, the IMF, and western capitalist powers did not only monitor but also support tyrant leaders in the process of transforming their countries to personalized autocratic unitary states where government serves leaders and not the people. Moreover, governance processes are marred by egoistic and self-enriching governing approach of governors. This rulership approach diverted the purpose of men forming government in Africa from one of serving the common good to one of serving the ruler’s good.

Rulers were furthermore able to secure their clutch to power through the construction of a solid neo-patrimonial structure, which depended on local and international resources to promote and enforce their authoritative resources. For example, late Omar Bongo’s neo- patrimonial rulership style in Gabon as illustrated by Douglas Yates shows the negative effect of neo-patrimonial rule in Africa. This neo- patrimonial rule significantly undermined the purpose of government: resources in the hands of rulers were used to pursue private aims and reward “political clients” to the detriment of the common good. Thus, Bratton and van de Walle argue that neo-patrimonialism is “the distinctive institutional hallmark of African regimes”.

The wrong allocation of resource is visible in the fact that heads of governments and their clients in Africa do not differentiate between their private and public possession. This results in widespread and institutionalized corruption and state theft with impunity. William Reno coins the result of this widespread corruption “shadow states”, lacking the bureaucratic separation of the private and the public’s sphere and, as a result, political power is treated as a personal property.

Power abuse—democracy versus autocracy: Proponents of authoritarianism assert that the establishment of systems of checks and balances hinders the ability and power to govern efficiently in many democratic systems. Such an assumption is fundamentally opposed to the system of checks and balances provided in democratic constitutions. Furthermore, pure technical leadership might create resistance, as seen in the revolutions of the last years (Egypt, Tunisia and Libya). In addition, a leader without accountability to the people often does not need to provide for his citizens. This often leads to bad governance, even if that efficiency was initially used to justify a strong ruler. From these arguments and with regards to autocracy, this assumption could be justified depending upon the rulership ideology in question:

An authoritarian leader who did not come to power through democratic election mechanism could suffer legitimacy, which he needs for his political authority. As a result, his ability to control depends upon his potential to oppress and/or use other “unconstitutional” persuasive and coercive means to rule. In Africa, where many leaders came to power mostly through coups in the early 1990s, the “non-democratic succession” is one reason for why they used autocratic, coercive and repressive methods of leadership to make up for their lack of democratic legitimacy.

Democracy requires that a government is limited and restrained by the other powers of the given constitution. A limited government is not a weak government. Limitation is simply the mechanism of curbing or restricting power abuse through its separation (counterbalancing effects) of political powers and by giving the people as the source of power the possibility to withdraw power when they perceive that the government is failing or when other leaders offer better options for the common good.

Power, whether legitimate or illegitimate, if it is not limited or checked is very susceptible to abuse. Authoritarianism in Africa fulfils conditions of power without legitimacy, that is, accession to power through coups d’état, appointment or “personal” succession, According to an analysis on how rulers leave power in Africa by Arthur Goldsmith, only one ruler left power through elections from 1960 to 1989 as opposed to 79 who left power through coups, wars or invasions.

Autocracy and its ability to oppress, coupled with greed and the human tendency to pursue self-interest, result in governments that oppose the common goal in Africa. Although not democratically elected, African governments were still expected to carry out the policies for the people. The right to rule, says Carl J. Friedrich, is founded upon a variety of beliefs and cultures, and it is possible for autocrats in Africa to feel entitled to their rulership, that is, to be accepted by their people to have the right to rule. Since the legitimate authority generally arises from receiving power from the people to serve their interest, the illegitimate use of this power is, therefore, an abuse of the power itself.

Generally, when the governors take up leadership positions, it predicates that they are accepting the responsibilities of taking care of the welfare of their people and serving the common interest of their nations. For William Antonio Boyle the beginning of moral evil is the rejection of the responsibility of those under one’s care. What is even worse is not only to reject responsibility but to go further to use leadership power for the pursuit of personal gains at the detriment of the governed—the people and thus the nation.

Leaning on the words “exploit” and “harm” used by Boyle and following his line of explanation in the case of Africa: autocrats who have power over their people by virtue of their accession or succession to power (regardless of how and why) and are “tolerated” by their people forcefully or without using force “somehow” have the trust of these people. However, when these rulers unjustifiably use this power to exploit and harm their people, fail to provide the necessary public services, vouchsafe corruption, oppress and utilize political authority for tyrannical actions profitable to themselves, then they are exploiting an harming their societies, and this is an abuse of power.

Power abuse is common in Africa and is facilitated by autocracy. The earmarks of authoritarian government include: supreme authority, the absence of accountability, the negligible value of popular participation in governmental process, the vertical flow of political orders in all public places and the absence of the right to remove an autocrat in case of the people’s dissatisfaction with his rule. All of these are typical indicators found in autocratic systems that existed and/or still exist in Africa.

Nations under such regimes are commonly identified by their “not-free” ranking in the World Bank Governance Indicators or Freedom House ranking. Considering the earmarks of authoritarianism, concludes that authoritarianism is by itself an abuse of power and leadership and it betrays the purpose of forming government. In Africa, power abuse is exercised in many forms, and with the introduction of democracy on the continent even more varieties of abuse now exist. The forms of power abuse occurring in Africa include: corruption; violation of the constitution or ignoring democratic elements in the constitution while enforcing the implementation of autocratic elements; extortion, which takes place through inadequate and excessive tax policies, which rarely completely enter government coffers; harassment of opposing political groups, rent-seeking, manipulation of elections and violation of the rights of individuals.

Autocrats lack compassion and find themselves in an unethical position where their personal interests conflict with the common interest of the nation. According to William Boyle, the situation of conflict of interest between personal and common interest is extremely unethical and governors who put themselves in such a situation are completely ignorant of leadership ethics. Conflict of interest is worse in Africa, where the governors satisfy their personal interests at the detriment of the people through the looting of state resources and the oppression and devastation of the people.

Leaders with statesmanship traits who give priority to the common good of their nations are lacking in Africa. Also, the right kind of constitutional and institutional arrangement with checks and balances and rule of law are absent. Current political arrangements are mostly based on clientele and patrimonial foundations, which facilitate self-enrichment, the consolidation and preservation of power for personal gains by the incumbent. Consequently, greed has established its roots even in institutionally supported forms.

Progress towards democratic governance despite the challenges of the past: Despite all the government failures and power abuse, true leadership is still possible if democracy is allowed to take its roots. In countries where it has been established, like Benin, Mali, Ghana and South Africa, functional governance is picking up and social and economic progress is recorded even when these countries do not have as many natural resources as their counterparts in more autocratic systems. The cases of successful transitions in Benin, Mali, Ghana and South Africa as opposed to the unsuccessful cases of Togo, DRC, and Cameroon are very indicative of the role that the leader can play in facilitating a successful transition. Their willingness to give up power and accept defeat in multi-party elections plays a decisive role in establishing democracy and achieving better governance. Bruce Magnusson and John Clark , using the cases of Benin (successful transition) and Congo (unsuccessful), have argued that personal leadership quality of the leader could determine the outcome of a democratic transition.

Their hypothesis only confirmed the 1982 study of Robert Jackson and Carl Rosberg, which clearly illustrated that the personality type of African leaders critically conditioned the type of polity established in Africa after independence. Furthermore, Kathryn Nwajiaku demonstrated in the cases of Benin and Togo that Kerekou’s magnanimity to submit to the will of the people and surrender sovereignty to the people, resulted in the success of Benin’s transition. In contrast, Eyadema stepped in to interrupt a similar conference in Togo, and put an end to a possibly smooth and successful transition.

Completed transition and successful democratic systems require committed people and great leaders that accept responsibilities out of a true sense of service to their people. Without democracy the people are more likely to suffer from autocracy and bad and dysfunctional governance. Furthermore, a people without democracy are exposed to violent challenges for political power, as no peaceful mechanism for transition exists. In countries where election manipulations are reported to have taken place, like in Cameroon during the 1992 presidential elections and in Kenya, during the December 2007 presidential elections, violent power struggles have been the result.

When we examine the long history of democracies, we could say that they have appeared weak and unstable; a few of them have also led to more authoritarian systems. However, even when these systems reverted, it was due to political failures and bad leadership. According to Afrobarometer surveys, the majority of Africans still prefer democracy to authoritarian rule, despite failed transitions and the shattered hope and enthusiasm that the wind of democratization brought with it.

This is due to the fact that in a democracy, it is not the democracy that is an end in itself, but each individual in the nation is regarded “as an end in himself and not merely a pawn to be manipulated for the benefit or privilege of a few”. Based on the merits of democracy personal freedom and citizens’ control over the government results in a more positive state of mind. This notwithstanding, democracies have also demonstrated remarkable resilience over time and have shown that, with the commitment and informed dedication of their citizens, they can overcome severe economic hardship, reconcile social and ethnic division, and, when necessary, prevail in time of war. This, however, needs time and means to complete the transition processes successfully, and commitment to consolidation by the peoples and governments in Africa.

Concluding remarks: Democracy, government, and governance all are necessary for a properly functioning nation- state. Some meaningful differences exist between them: they are not mutually exclusive of one another. These three political components have been connoted only with negative adjective in contemporary African political systems. The post-independent states started off with democracy but were gradually and “illegitimately” transformed to more centralized autocratic one party states where the governments were not of and by the people with subsequent bad governance.

Good governance is not achievable if the right institutions and institutional arrangements are not in place. A functional state, where the common good of the people has unquestionable priority, the political system is democratic, and government and governance are in their best forms is still a political luxury in many African countries. From its definition, democracy is a government for and by the people: that is, it is a government that comes from the people and has the function of serving the people.

Democracy has two important dimensions: elections and participation are indispensable for a successful government and subsequent good governance. Rigging or manipulating election results and denying people the right to participate in governance processes prevents democracy. Furthermore, neo-patrimonialism and lack of statesmanship, especially the non- magnanimous character of the leaders, result in failed and stalled transitions. The outcome is democracy with adjectives indicating their shortcoming or incompleteness. Thus, there are multi-party systems where only the party in power wins elections.

The autocratic leaders allow opposition parties to operate but deny them victory. The role of institutions to separate power and “limit” the autocratic ruler is guaranteed only through adherence to constitutional arrangements. This can occur through a re-constitution like in Benin in 1990, Ghana in 1992, Mali in 1992 and South Africa in 1994. This can mean putting an end to the authoritarian system and not only amending sections of an authoritarian constitution but also legalizing opposition parties. In such cases (Cameroon, Gabon, DRC, Togo, the list is long) the autocratic component of the autocratic constitutions remain dominant rendering a complete transition process as well as a functional democracy impossible.

Thus, even though consolidation takes place it is not a consolidation of democracy since transition is not yet completed, but consolidation of autocratic rule against the success of democratization. According to Samuel Huntington a successful transition has three stages:

(1) the end of an authoritarian regime,

(2) the installation of a democratic regime, and

(3) the consolidation of the democratic regime.

Autocratic constitutions and leaders who put their personal interest ahead of the common interest of their nations have ruined and derailed many transition processes in Africa as many incumbents manipulated and rigged or even rejected election results that disfavored them.

Therefore, as a forced transition is not desirable, re-constitution requires responsible leadership that allows the setting up and implementation of a democratic constitution. Furthermore, the implementation of the democratic constitution also means practical establishment of the right institutional arrangements safeguarding separation of powers, rule of law and an accountable government.

By doing this leader must put the people first and not bother about losing the next democratic elections if that is the will of the people. Governance in a next step goes beyond democracy and includes making and implementing the right political decisions, getting and facilitating the involvement of all the important and necessary public and private actors in the management of the state for the common good. The relationship between democracy and good governance still makes the difference: democracy cannot guarantee good governance as a state may as well be dragged into crisis, conflicts and other problems by the poor leadership of a democratically elected leader. However, with democracy the people are able to sanction such a leader during periodically organized elections by voting him out.

Thus, true leadership with functional governance is still possible in Africa if democracy is allowed to take its roots as in Benin, Ghana and South Africa where democracy has been established.

Dr. Joy Alemazung is a Senior Analyst in the Peace and Security Section focusing on state transformation and on good governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. He is also a Lecturer at the University of Applied Sciences, School of International Business in Bremen, Germany. He is the Managing Editor of the Global Applied Sociology Journal, a Fellow of the African Good Governance Network at DAAD, and a reviewer for the African Journal of Political Science and International Relations. He has published amongst others, on the impact of the financial crisis on the reforms in sub-Saharan Africa, and on the African Political System. Dr. Alemazung holds an MA in Political Science and Sociology from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and a PhD in Political Science on the States Constitution, Political Transformation and Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa from the University of Kiel, Germany. His upcoming monograph “State Constitutions and Governments without Essence in Post-Independence Africa: Governance along a Failure-Successful Continuum with Illustrations from Benin, Cameroon and the DRC” will be published in early 2013.

Dr. Joy Alemazung is a Senior Analyst in the Peace and Security Section focusing on state transformation and on good governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. He is also a Lecturer at the University of Applied Sciences, School of International Business in Bremen, Germany. He is the Managing Editor of the Global Applied Sociology Journal, a Fellow of the African Good Governance Network at DAAD, and a reviewer for the African Journal of Political Science and International Relations. He has published amongst others, on the impact of the financial crisis on the reforms in sub-Saharan Africa, and on the African Political System. Dr. Alemazung holds an MA in Political Science and Sociology from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and a PhD in Political Science on the States Constitution, Political Transformation and Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa from the University of Kiel, Germany. His upcoming monograph “State Constitutions and Governments without Essence in Post-Independence Africa: Governance along a Failure-Successful Continuum with Illustrations from Benin, Cameroon and the DRC” will be published in early 2013.