PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

INSIDE THE MINDS OF AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES

The Roots of the Authoritarian State in Africa: African politics in the post-colonial era has been marred by authoritarianism, corruption, military intervention, and leadership failures amidst a broader socio-economic crisis characterized by poverty. Upon obtaining independence from colonial rule in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the public mood was marked by exuberance and hope for immediate and substantial changes. Equally, the political landscape, fueled by the triumph of independence and corresponding empowerment, fostered an atmosphere of high expectations for a better future for Africans. This enthusiasm, however, was short- lived.

The new political leadership quickly learned that the aftermath of colonial rule presented an enormous challenge to meaningful socio-economic development and state consolidation. The interplay of such challenges, personal ambitions, and political unrest prompted a downward spiral in African politics. Something went terribly wrong in the initial progression of self-governance upon independence. Here, we will outline this progression of political developments and demonstrate the entwined nature of political, social, and economic dynamics. We will begin to explore why African governments became increasingly authoritarian and unable to sustain democratic political systems. A consideration of the role of colonialism in the development of African politics upon independence is included.

Independence for most African states came abruptly. While independence had been the goal of political activism, it was not the end product of a long process of preparation from either side of the colonial spectrum. Few, if any, African leaders had thought about the ‘post’ independence period; no explicit and specific plans were made with respect to political governance upon independence. And European colonizers failed to prepare African states for the end of colonial rule.

Only Great Britain and France, among all colonizing states, made any attempts to establish the institutions and skills necessary for successful self-rule before independence. However, the democratic models created for the British and French colonies lacked any cohesion with existing political structures and norms. They were “essentially alien structures hastily superimposed over the deeply ingrained political legacies of imperial rule”. Perhaps the fact that the successful transfer of power, at times, was actively sabotaged by European administrations underscores the lack of commitment to African independence on the part of the colonizing powers. In Guinea, for example, the French dismantled the entire bureaucracy before leaving the country. All paper documents were destroyed leaving the new Guinean government with no records whatsoever.

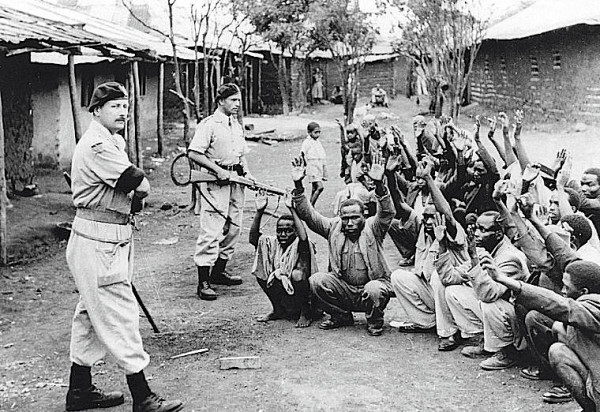

The political legacy of colonialism, then, has nothing to do with the artificial democratic government models that some European colonizers left behind. Rather, the dual legacy of authoritarian rule and artificial nation-states coalesced to pose complex challenges to newly independent African states. Specifically, colonial administrative systems were not based on democratic foundations. Governance followed a ‘from the top down’ approach that was largely arbitrary and not geared towards the well-being of the governed. The purpose of colonial government was to control the population and ensure the continuous exploitation of natural resources for the benefit of the European colonizing powers. This purpose was met with authoritarian rule and bolstered by strong police and military forces. Power rested with the colonial authorities who maintained their authoritarian status with force; consequently, political legitimacy was attached to the unequivocal control of force. This system of authoritarian rule, then, is the political system with which most African leaders were familiar. Colonialism implanted the notion that authoritarianism is an appropriate mode of political rule and that force is an acceptable instrument of that rule.

Such a dogmatic conception of political governance was accompanied by the artificial state boundaries bequeathed to independent Africa. European powers had created colonies that were comprised of many different language, religious, and ethnic groups. Also, through the emphasis on tribal/ethnic identity, colonial governments created societies that were often deeply divided along ethnic lines. At the point of independence fears of state dissolutions along ethnic lines were prevalent (the Biafra War actually was fought over the secessionist aspirations of one ethnic group in Nigeria). While such diversity is not necessarily a hindrance to successful government, the deep societal divisions created by colonial policies posed significant challenges to African governments. The ideal of national unity remained elusive which rendered the goal of state consolidation even more difficult.

The political ramifications of colonialism, in the form of authoritarianism and artificial state boundaries, were supplemented with a corollary of economic circumstances that were equally as debilitating for newly-independent Africa. The colonial authorities, in their attempts to obtain the maximum economic benefit from their colonies, subordinated the colonies to the economic needs of Europe. Hence, economic policies were determined by the nature of the exploitable resources and the needs of Europe.

Therefore, four distinct economic zones emerged in colonial Africa—these zones were based on local realities and determined the economic activities that took place throughout the continent. Regardless of the specific economic policies and activities of any colonial state, the outcome was surprisingly uniform across Africa. Colonial economic undertakings were completely geared toward the generation of profits for European companies, banks, governments, administrators, and settlers. African development was not a concern of any such economic undertakings. The assertion that colonialism ‘underdeveloped’ Africa is clearly debatable. What is not debatable, however, is the fact that colonial economic policies undermined the economic future of independent Africa. Colonialism altered and undercut African socio-economic developments while simultaneously creating maladjusted, feeble economies. At the point of independence African states were forced to compete in the international arena with incredibly weak economies; dependency relationships were almost foreseeable.

The colonial experience clearly played a significant role in shaping the framework for political activity in independent Africa. Of equal importance were the beliefs, characteristics, and undertakings of the politicians leading the anti-colonial struggle. It is these leaders who came to shape the new governments upon independence. Their activities, in conjunction with socio-economic realities, were crucial in molding the direction of African politics. Specifically, in an environment dominated by abject poverty, the separation of public and private life is not easily maintained. Hence, many leaders of the anti-colonial struggle hoped to convert their leadership positions into individual mobility. Political office was seen as a path away from poverty; a tendency to cling to political office quickly came about.

Additionally, pre-independence political activity laid the groundwork for the emergence of political parties along regional/ethnic lines and the patron-client relationships. To garner mass support in an environment dominated by poor transportation and communication infrastructure and wide dispersal of populations, politicians naturally turned toward their own villages and ethnic groups. It was among these groups that politicians could most effectively create large support bases which eventually would become political parties. One of the strategies employed by politicians to win support was to make promises of material assistance. Such promises in exchange for support and votes became the basis of the patron-client relationships that came to pervade African politics in the post-independence period.

The colonial period in Africa lasted less than a century and ended (for the most part) over half a century ago. Yet its implications continue to play a part in the political and socio-economic developments of the continent. African governments at independence inherited bureaucracies and economies that did not have the capacity to meet the tremendous challenges that lay ahead. New nationalist governments, nonetheless, came to power on the promise that they would work towards meeting the needs of all citizens, especially in the areas of health care, education, sanitation and infrastructure. The legitimacy of the first independent governments in Africa depended on their ability to meet these needs.

Yet weak government structures, lack of funds, and limited number of qualified leaders proved to be immense obstacles to the successful implementation of policies. But expectations were high and could not be fulfilled immediately; hence political dissatisfaction and unrest resulted.

The monumental achievement of African independence itself could do little to offset the less than auspicious set of circumstances that African leadership had to face once the transfer of power was complete. High expectations, lack of financial resources, political fragmentation, lack of national unity, and inexperience conspired to create extremely insecure governments. To counteract the enormous expectations and to create a political space in which to pursue policies, most governments began to consolidate power and expand political control.

This was achieved principally through the elimination or curtailing of opposition and the expansion of bureaucratic agencies including the military and police forces. The deliberate and persistent dismantling of democratic structures and institutions that were present at the time of independence was justified with a strong belief that a powerful central government was necessary to ensure economic development and national unity. The single-party state became the norm in African politics as early as the late 1960s. Authoritarianism began to replace democratic means of governance as all political power came to rest in the executive branch. That means that the presidencies, through control of the security forces and the bureaucratic agencies, came to determine the structures, institutions, and policies of African politics. The consolidation of power was complete, yet political opposition was not eliminated.

Political opposition continued to be expressed through ethnic and/or regional channels as politicians who lost out in the power consolidation moves appealed to those groups who were perceived not to be favored by the presidency. Consequently, the ruling elite saw itself forced to build stronger foundations of political support. It used patronage and the resultant patron-client ties to co-opt opposition and ensure broader support for its position in government. Patronage came to be a defining element in African politics as explained in the following excerpt by Donald L. Gordon:

“The fact is that patron-client relationships permeate most African governments. Citizens “tie” themselves to patrons (from their kinship line, village, or ethnic, language, or regional group) in government who can help them in some way. Lower-level patrons invariably are clients themselves to a more important patron who may have been responsible for securing his ethnic “brother’s” job in the first place. At the upper end of patron-client networks are “middlemen” clients of the ruling elite. Using political clout, powerful positions, and access to government monetary resources made available by the rulers, these middlemen-patrons not only supply jobs in government but money for schools, health clinics, wells, storage facilities, roads, and other favors to their ethnic groups and regions. Patronage binds local constituencies not only to their network of patronage but also to support for the regime itself. Emanating from the country leader may be literally hundreds of patron-client linkages that fix support of other elites to the country’s leadership and create substantial support for the regime.”

The consequences of the pervasiveness of patronage are manifold. The intended objective of creating larger support bases and deflating opposition forces was certainly met, at least initially. However, patronage also reinforced the politicization of ethnicity as ethnic identity continued to remain one of the criteria for allocating resources. Perhaps most important is the effect of patronage on the national coffers. Patronage, as a tool for political acquiescence, requires large amounts of money. African leaders, in their attempts to build stable governments and remain in power, were forced to invest more and more resources into the patronage networks. This, in turn, had detrimental consequences on the ability of African states to meet their financial obligations in general and to pursue any meaningful development policies in particular.

African governments’, civilian or military, preoccupation with the consolidation of power and the accompanying use of patronage as a form of political control and governance led to a draining of state resources. Already meager resources, one could argue, were squandered on maintaining patron-client networks rather than invested in desperately needed development programs. One of the preferred ‘favors’ in patron-client relationships was the allocation of jobs; this resulted in the exponential growth of the civil service and government-owned businesses during the 1960s and 1970s. The outcome was an unsustainable financial burden on the state. “By 1980, at least half of all government expenditures were allocated simply to pay the salaries of government employees.”

Such financial obligations required innovative solutions to raise money. In the absence of strong donor income and domestic industrial bases, African governments increasingly turned toward the agricultural sector as a source for desperately needed revenues. African governments manipulated the agricultural commodities markets to their benefit and the detriment of rural farmers. Such policies allowed the ruling elites to maintain themselves for a while longer while simultaneously undermining the one economic sector upon which successful development policies could have been based on. Additionally, such policies profoundly influenced societal dynamics throughout sub-Saharan Africa. They gave rise to increased rural to urban migration and prompted an extensive disengagement from the state. Political dissatisfaction and the conditions for unrest began to manifest themselves.

By the early 1980s, most African states were no longer able to meet their financial obligations. Declining prices for African agricultural and natural resource exports, rising oil prices, increased costs of African industrial imports, growing populations and mismanaged budgets combined to put the African state into crisis. Most state governments were severely weakened during this time as the most basic public services could no longer be carried out. Governance continued on its downward spiral as people increasingly created their own communal support systems in response to the state’s inability to provide services.

The informal economy grew; corruption became rife; and credit dried up for African governments. Heavy lending from international entities allowed African governments to function at a minute rate. But by the late 1980s and early 1990s, sub-Saharan Africa’s debt burden had become so colossal that international lenders were no longer willing to extend credit to African states. African states were forced to agree to the harsh austerity programs from the lenders of last resort, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

The vast majority of sub-Saharan African states became borrowers of the IMF; this meant that they had to implement the IMF’s structural adjustment programs (SAP). SAPs are very controversial. Suffice it to say at this point that these austerity measures had profound consequences in the political and economic relationships and dynamics of sub-Saharan Africa. The legitimacy of African governments, arguably, was undermined by SAPs as monies for patronage networks were curtailed, food subsidies were eliminated, and governments were forced to cut  essential services (health care, education, etc.). The very existence of African authoritarian governments was put into question. Such policies, of course, were felt by ordinary citizens.

essential services (health care, education, etc.). The very existence of African authoritarian governments was put into question. Such policies, of course, were felt by ordinary citizens.

The direct impact of the austerity measures on people’s lives blended with several external events and dynamics and gave rise to reinvigorated opposition forces within African states. Specifically, the end of the Cold War and the subsequent wave of democratization through Eastern Europe left its mark on Africa. Africa lost strategic importance with the end of the Cold War and was increasingly confronted with new policy objectives by foreign powers. Democracy and respect for human rights became important features of US, German, British, French, etc. foreign policy. Such international dynamics weakened African authoritarian governments and strengthened the opposition. Open challenges to Africa’s ruling elites and demands for political change became almost routine.

The political transformations so characteristic of the 1990s did not bypass Africa. Many African states experienced significant political change during this decade. Reforms were undertaken leading to increased political space. Political parties were legalized and multi-party elections were held. Several states saw the peaceful transfer of power; South Africa’s apartheid regime came to its end; political liberties were expanded.

However, the democratization process is far from complete. The initial excitement and speed with which political reform was carried out abated as most African states experienced an erosion of the progress that was achieved. Some African leaders continue to manipulate the system (alter constitutions and electoral laws, control campaign resources, etc.) in order to stay in power. Nonetheless, no longer is it the case that the vast majority of African states have autocratic governments engaged in patrimonial rule. Most states have engaged in some form of democratic reform and public support for democracy is widespread throughout the continent.

The trajectory of African politics since independence appears abysmal. African politics must be understood in the context of historical dynamics both internal and external to the continent. It is impossible to divorce current and future African political activity from the foundations laid down during the colonial and post-colonial eras. Despite the apparent inabilities of African states to successfully engage the challenges of independent Africa, one should not dismiss the achievements of African people. It is the efforts of African people that have resulted in a truly remarkable evolution of Africa and African politics. For example, the engagement of individuals has brought the Liberian civil war to its end and seen two successive peaceful elections in that country.

In addition, the Green Belt Movement, initiated by Wangari Maathai, has given rise to successful environmental recovery, grassroots development, and issue linkage not just in Africa but around the world. On a final note, one significant example of positive political engagement is the drafting and adoption of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Banjui Charter) and subsequent developments in human rights law. Specifically, the Banjul Charter is the first international human rights document that explicitly recognizes the need to integrate and balance individual and collective human rights; this is a concept with which ‘western’ states continue to struggle. Thus, African states also contributed positively to international and global affairs during the chaotic and often violent post-colonial period.

Source: The Saylor Foundation (www.saylor.org/political science/African politics)