PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

THE AU AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT

Max du Plessis, Tiyanjana Maluwa and Annie O’Reilly: More than two-thirds of the members of the African Union (AU) are parties to the treaty establishing the International Criminal Court (ICC Rome Statute). Nevertheless over the years the Assembly of the AU has adopted various resolutions critical of the ICC and its practice. This paper discusses some of the reasons for the apparent antagonism of the AU towards the ICC.

Among the questions addressed are: whether the ICC is guilty of selective prosecution of cases originating in Africa; why the AU is so critical of the ICC and how its attitude has evolved over the years; how is the ICC constrained by the customary international law doctrine of head-of-state immunity; the extent to which the prosecution of Kenya’s president and deputy president pose a real challenge to the ICC’s authority; the problem of witness protection before the ICC; the principle of complementarity in the African context; the AU’s attempt to establish a regional court to try international crimes; and finally, the road ahead and whether it is likely that the AU will ever permit the ICC to open a liaison office in Addis Ababa.

SELECTIVE PROSECUTION: All of the cases that the ICC is currently investigating and prosecuting have to do with crimes allegedly committed in countries in Africa. This has raised questions as to whether this is an example of the selectivity of international criminal law.

Countries from the global south frequently complain of skewed power relations in the UN Security Council. This imbalance has affected the ICC because, under the Statute of the ICC (the Rome Statute), the Security Council has the power to refer cases to the court. The Security Council has referred some cases—Libya and the Sudanese region of Darfur—but not others, such as Israel and Syria. The fact that the two situations that have been referred come from Africa tends to support the suggestion that there is an anti-African bias. This has been effectively argued by John Dugard, in relation to Israel, in the most recent issue of the Journal of International Criminal Justice.

There are good reasons to pursue the cases that are under investigation or prosecution before the ICC. For one thing Africa has experienced a large number of atrocities and, statistically speaking, the rate of atrocity crimes committed on the continent would make it a natural focus for the court anyway. The victims of those crimes want justice. The people who complain about the bias tend to be African political elites, not the victims, who appear to be almost universally relieved that somebody—anybody—is paying attention to their plight.

However, there is a genuine problem, which has to do with perception and the need for the ICC to be seen to be acting in a just manner in order to maintain its authority. The universal aspirations of international criminal law are inconsistent with a focus that is limited to African states, in a world in which many other states—particularly powerful ones – act with apparent impunity. The refusal by Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa in 2012 to share a stage with former British Prime Minister Tony Blair in Johannesburg, based on the latter’s actions over the war in Iraq, called attention to this apparent moral ambivalence in relation to the way the ICC works. Tutu’s moral authority helped to demonstrate that this perception problem is very real.

Failure to take this problem seriously has provided some African politicians and officials with ammunition to argue that the ICC is selectively biased against Africa. This distracts from the very real plight of victims of war crimes and crimes against humanity which have taken place on the continent.

The previous chief prosecutor of the ICC, Luis Moreno Ocampo (2003–12) exacerbated the situation by failing to communicate with his African interlocutors, particularly by failing to partake in discussions with the AU. The former chairperson of the AU Commission (2008–12), Jean Ping, even stated that ‘[f]rankly speaking, we are not against the ICC. What we are against is Ocampo’s justice.’

However, it is important to remember that there only two situations of which the ICC is seized because of the prosecutor’s proprio motu powers—those relating to Kenya and to Côte d’Ivoire. In the case of Côte d’Ivoire, the government willingly accepted the court’s jurisdiction before becoming a state party in order to allow the prosecutor to commence a case there. In four situations before the court—Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the Central African Republic and Mali—the states themselves referred the cases (though the prosecutor retained the final say on whether these cases were pursued). The further two situations – Libya and Darfur – were referred by the Security Council. Given that states and the Security Council have referred a majority of the cases before the court, the more pressing issue, as far as the prosecutor’s alleged bias is concerned, may be the non-pursuit of situations and cases from other parts of the world, rather than the pursuit of African situations and cases.

But at the same time, state referrals should not be understood as wholesale endorsements of international criminal justice. In some instances, African governments have referred cases in order to manipulate the international criminal justice system for their own political purposes. For instance, President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda initially referred cases involving the Lord’s Resistance Army to the court but now takes a leading role in the AU’s campaign against the ICC. He has been even more vocal about his opposition to the ICC than the AU’s current chairman, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn Boshe of Ethiopia, who recently announced that the organization opposed the prosecution of President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya for crimes against humanity and promised to raise the matter with the United Nations.

THE AU’S POSITION ON THE ICC: A large number of African states are states parties to the ICC’s Rome Statute but the AU is very critical of the ICC and has adopted a number of resolutions reflecting this. Yet most African states at one time strongly supported the ICC. They were very active in the negotiation of the Rome Statute in the late 1990s. This was a time of great optimism, particularly because the statute had not just the backing of African governments but also of African NGOs, grouped under the International Coalition for the ICC.

The turning point came in 2000 when Belgium issued an arrest warrant for the DRC’s then-minister of foreign affairs, Abdoulaye Yerodia Ndombasi. This was not well-received in Africa and began to sour relations between Africa and Europe over the issue of sovereign immunity. Then, in 2008, the chief of protocol to President Paul Kagame of Rwanda, Rose Kabuye, was arrested in Germany pursuant to a French arrest warrant in connection with the shooting down of the former Rwandan president’s plane, which triggered the 1994 genocide. Kagame took up the issue at the UN, framing it as an abuse of universal jurisdiction by European states aimed at humiliating African political leaders. These are just two examples in a series of cases in which European states relied on universal jurisdiction to harass, in the eyes of some observers, African leaders.

In 2008, the AU reacted to the increased use of universal jurisdiction in European states by adopting a resolution denouncing certain Western governments and courts for abusing the doctrine of universal jurisdiction and urging states not to cooperate with any Western government that issued warrants of arrest against African officials and personalities in its name.

The watershed moment for the AU’s relationship with the ICC came in March 2009, following the issuance of the first arrest warrant for President Omar al Bashir of Sudan. For states parties to the Rome Statute, this transformed it from a ‘paper commitment’ with no real consequences into a very real commitment with potentially serious consequences.

The Bashir arrest warrant caused the relationship between the ICC and the AU to deteriorate for two reasons. First, members of the AU felt that the issuance of the arrest warrant was an impediment to the organization’s regional efforts to foster peace and reconciliation processes in Sudan, and that the ICC failed to appreciate the effect that its actions were having on these efforts. Secondly, diplomatic umbrage was taken over the indictment of a sitting head of state, which sparked a debate over whether the Rome Statute can legitimately extinguish diplomatic immunity in states that are not parties to it, such as Sudan.

The AU’s opposition to the ICC has created a legal conflict for states that are parties to both institutions; different governments have chosen to resolve it in different ways. For instance, when President Jacob Zuma was due to be inaugurated in South Africa, invitations were sent out to all African heads of state, including President Bashir. As a party to the Rome Statute, South Africa would be required to arrest President Bashir, if he attended the event. Overnight this created a diplomatic scandal that was very difficult for South Africa to deal with. After two or three days’ silence from the South African government on the issue, civil society representatives threatened to request declaratory relief from a court that if President Bashir were to arrive in South Africa there would be an arrest warrant issued for him. The government eventually took the position that it would be under an obligation to arrest Bashir if he arrived in South Africa, and the Sudanese president did not attend the inauguration. South Africa’s position—that it is bound by the Rome Statute—has been clear and consistent since then. But it is likely that many other African states faced with a similar choice would side with the AU, not the ICC.

In October 2011, when Bingu wa Mutharika was Malawi’s president, Bashir attended a for the Common Market for Eastern and Southern African States summit in that country. Malawi issued a formal memorandum in support of its decision to host Bashir, in which it relied on (i) the AU’s resolution, passed in response to President Bashir’s arrest warrant, urging states not to cooperate with the ICC, (ii) the customary international law doctrine of head-of-state immunity and (iii) the fact that Sudan was not a party to the Rome Statute and could therefore not be bound by its suspension of immunity, to demonstrate that it was not under obligation to arrest him. However, in June 2012 the current President of Malawi, Joyce Banda, refused to allow Bashir to attend an AU meeting in Malawi, forcing the organizers to move the meeting just three weeks before it was scheduled.

In 2011, the National Transitional Council (NTC) in Libya allowed Bashir to visit Tripoli but, surprisingly, NATO states made no attempts to intervene in the matter. Indeed, Bashir was the first foreign head of state to visit the NTC in Libya after the fall of the Gaddafi regime, as the Sudanese president provided assistance to the rebels in Benghazi as ‘payback’ for Gaddafi’s assistance to rebels in Sudan’s Darfur region. The fact that Libya is not a party to the Rome Statute partly explains the NTC’s failure to arrest Bashir, but it does not explain why NATO member states like the United States and the United Kingdom who undoubtedly had a moral responsibility to do something failed to intervene.

THE ICC AND STATE IMMUNITY: The question of immunities is central to the AU. One interpretation of Article 27 of the Rome Statute, which provides that state immunity does not apply under the statute, is that it creates an exception to customary international law and allows heads of state and other senior state officials to be tried in this particular jurisdiction.

Article 98 of the Rome Statute appears to conflict with Article 27, however, by providing that the ICC may not request cooperation or surrender from a state where that would require that state

to act inconsistently with its obligations under international law with respect to the state or diplomatic immunity of a person or property of a third state, unless the court can first obtain the cooperation of that third state for the waiver of the immunity.

But there appears to be an acceptance that states parties, by virtue of becoming members of the Rome Statute, have waived the immunity of their own officials or have otherwise accepted that they do not have immunity. So, at least as far as states parties are concerned, Article 98 does not apply, and there is no immunity before the court.

The difficulty arises in respect of states that are not parties to the Rome Statute, such as Sudan. There are a variety of views on this issue. It has been argued that in this situation, it is irrelevant that Sudan is not a state party because the case was referred by a Security Council resolution, which is are binding on all UN member states.

In 2012 the AU Assembly asked the AU Commission to consider whether it would be possible to request an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the question of immunity. While this initiative may not be successful, it is commendable that the AU has sought to resolve this matter through respected international law channels. It is clear that the question of immunity raises important, unresolved questions.

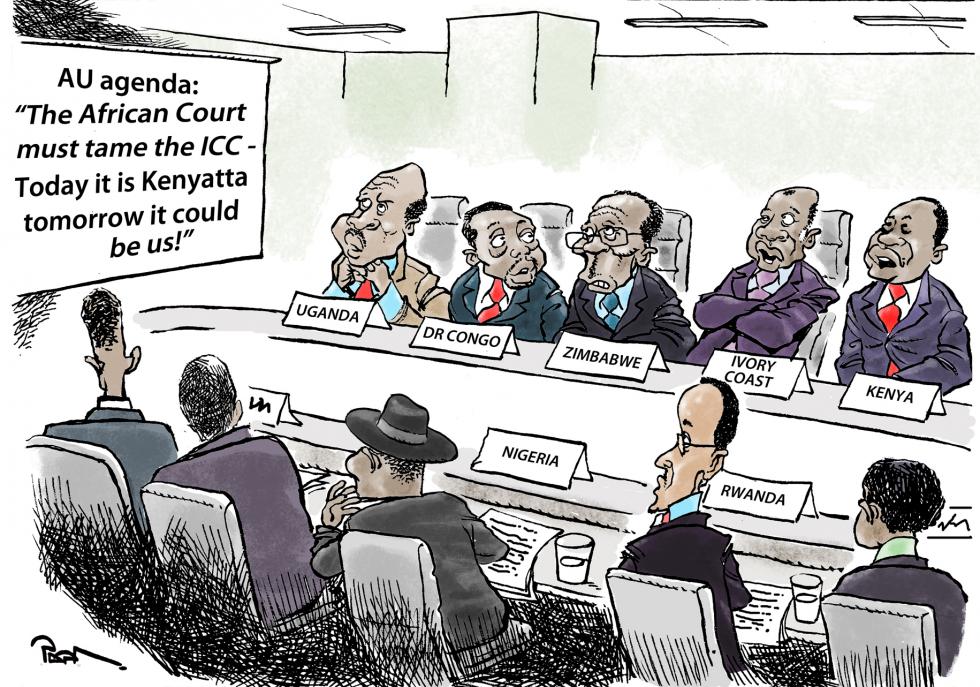

THE KENYAN CASES: Are the cases against President Kenyatta and Deputy President Ruto so sensitive throughout Africa as to pose a real challenge to the court’s authority? In May 2013, the Kenyan government successfully lobbied AU members to adopt a resolution calling for the cases to be referred to Kenya for national proceedings to be taken, rather than being left to the ICC. The resolution was supported by all states except Botswana.

The resolution regrets that the AU request to the Security Council to use its powers under Article of the Rome Statute to seek a deferral of the Bashir case was not acted upon. It reaffirms that countries such as Chad, which previously welcomed Bashir, did so in conformity with the decisions of the AU Assembly and therefore should not be penalized. It also stresses the need for international justice to be conducted in a transparent and fair manner in order to avoid any perception of double standards, and ‘expresses concern at the threat that the indictment[s …] may pose to the on-going efforts in the promotion of peace, national healing and reconciliation, as well as the rule of law and stability, not only in Kenya, but also in the Region’. And, finally, the resolution requests a referral (presumably by the Security Council) of the cases back to Kenya in order for its reformed judiciary to deal with these matters.

Four points are noteworthy about the AU’s resolution. First, nowhere does it mentions the victims of the violence or the citizens of the affected states. Second, the AU appears to have moved on from the Sudan issue, and is now focused almost entirely on Kenya. Nothing, except Kenya’s persistent lobbying, adequately explains why Kenyatta’s and Ruto’s cases have proved more galvanizing than Bashir’s. In further evidence of Kenya’s effective lobbying campaign, the Kenyan government managed to put the issue on the AU’s agenda just five days before the session, despite the agenda having been drawn up well in advance. Third, the claim that the judiciary is reformed is one with which many Kenyan human rights and criminal justice experts disagree. A group of these experts has written to the UN secretary-general stating that there is no process of reconciliation, no mechanism to try these cases in Kenya and the threat of instability in the region is hollow.

Fourth, there was an attempt to move the AU members to withdraw from their treaty obligations under the Rome Statute, though from the text of the resolution it appears that the attempt has failed for now. It is not clear that there is any legal basis for the AU to require its members to withdraw from their treaty obligations that were entered into voluntarily and on an individual basis. The resolution ends by asking the AU Commission to organize a

brainstorming session as part of the 50th Anniversary discussion on the broad areas of International Criminal Justice System, Peace, Justice and Reconciliation as well as the impact/actions of the ICC in Africa, in order not only to inform the ICC process, but also to seek ways of strengthening African mechanisms to deal with African challenges and problems.

Although parts of the Kenyan government appear to have been lobbying hard against the ICC, there is an apparent lack of coordination within it on this issue. While Deputy President Ruto was in The Hague at a status hearing of the ICC, the Kenyan permanent representative at the UN submitted a letter to the Security Council, apparently on behalf of the government, requesting it to instruct the ICC to discontinue these cases. This was just days before the ICC prosecutor was due to address the Security Council. It is claimed that Ruto was not informed of the letter in advance and subsequently issued a letter to that effect and re-committing himself to cooperation with the ICC’s legal process. Efforts by the government to block the trials from going ahead, or effect their referral back to Kenya, are unlikely to be successful; decisions on complementarity are for the ICC alone. And the fact that Kenya has not put in place the necessary legal framework to try these cases properly gives the lie to the claim that the cases ought to be referred back to it. But despite the apparent futility of Kenya’s campaign as it relates to Kenyatta and Ruto, it may be that in the long run, the cases may lead to the irretrievable breakdown of the relationship between the AU and the ICC.

WITNESS PROTECTION: In the Kenya cases, the issue of witness protection has been of some significance. In many cases before the ICC, the identity of witnesses is revealed long before the court starts investigating the case. Is there anything that can be done about the difficulties the ICC faces in ensuring adequate witness protection?

One of the main problems with the ICC’s witness protection program is that it must rely on local partners to carry out protection measures. In Kenya, for instance, two witnesses have disappeared, while others are ‘recanting’. Were these cases to be referred back to Kenya, where the witness protection agencies are accountable to the accused, it is extremely unlikely that the necessary testimonies would be obtained. This makes it all the more important that the cases remain at the ICC.

One complication in the Kenya cases is that it was originally envisaged that witnesses on one side of the political divide would testify against perpetrators on the other side of the political divide. But now that Ruto and Kenyatta have formed a coalition, witnesses are required to testify, essentially, against their own. It is unclear how the Kenyan judiciary would deal with this problem.

UNIVERSAL JURISDICTION: A fundamental aspect of the ICC statute is that the court can only try cases where domestic courts are unable or unwilling genuinely to investigate or prosecute (the complementarity principle). The ICC cannot deal with many cases itself, and domestic proceedings could be increased by use of the principle of universal jurisdiction that allows any state to try perpetrators of international crimes in its own courts, wherever the crime is committed. But there has been resistance on the part of African states to the exercise of universal jurisdiction. It is unclear whether there is a future for the principle so far as African states.

While African states have their complaints about the abuse of universal jurisdiction by European states, there remain rich possibilities for them to utilize their own domestic processes in pursuit of universal justice in preference to the ICC. The ICC is one component of a regime made up of a network of states that have undertaken to advance international criminal justice alongside or as a complement to the ICC, acting as domestic international criminal courts in respect of ICC crimes. In this respect, as Anne-Marie Slaughter has pointed out,

One of the most powerful arguments for the International Criminal Court is not that it will be a global instrument of justice itself – arresting and trying tyrants and torturers worldwide – but that it will be a backstop and trigger for domestic forces for justice and democracy.

The very principle of complementarity makes it clear that, by domestic investigators and prosecutors acting against international criminals, national courts ensure the international rule of law through a mutually reinforcing and complementary international system of justice. As Antonio Cassese pointed out in 2003, there was a practical basis for this principle when the Rome Statute was being negotiated:

It is healthy, it was thought, to leave the vast majority of cases concerning international crimes to national courts, which may properly exercise their jurisdiction based on a link with the case (territoriality, nationality) or even on universality. Among other things, these national courts may have more means available to collect the necessary evidence and to lay their hands on the accused.

Thus, rather than perceiving the ICC as an instrument of global or universal (in)justice disrespectful of particularly African states’ sovereignty, the very premise of complementarity allows African states to demand that the ICC defers to their competence and right to investigate international crimes. As Slaughter argues, the choice is for a nation to try its own or they will be tried in The Hague. Instead of weakening states and undermining sovereignty, properly understood the ICC regime does quite the opposite: it ‘strengthens the hand of domestic parties seeking such trials, allowing them to wrap themselves in a nationalist mantle’.

There is a vital role for domestic proceedings to play. The important and positive role that complementarity has already played in the work of civil society and domestic institutions in responding to African crimes must be noted. Despite the AU’s bitter contestation with the ICC at the political level, on the ground domestic investigations and prosecutions of international crimes have shown promising signs of a home-grown form of international criminal justice that should serve as an example beyond Africa.

In this respect an important judgment was recently handed down by the South African High Court, which confirmed that South African authorities are under an obligation to act as a complement to the ICC in investigating – through the use of South Africa’s universal jurisdiction provisions in its ICC implementation legislation—purported acts of torture committed in Zimbabwe by Zimbabwean police officials against Zimbabwean victims.

And the AU’s attempts to coordinate an ‘African’ response to the ICC have been undermined on various respects. In an example already mentioned, South African civil society mobilized in 2009, threatening to seek a court order for the arrest of Bashir after reports that Bashir had been invited to attend President Zuma’s inauguration in Pretoria. In respect of Kenya, Bashir tried on one occasion to turn up as a guest at the country’s celebration of its new constitution in August 2010. In response to criticism of its decision to host the president of Sudan, and in reaction to a reported follow-up visit by Bashir to attend a summit in Kenya two months later, Kenyan civil society went to court and obtained a court order for the provisional arrest of Bashir should he enter the country’s territory. He has not returned since.

A number of heartening African developments have taken place recently, which flow from a proactive form of complementarity. As well as the examples in South African and Kenya, Uganda and the DRC have initiated prosecutions of those involved in the commission of international crimes within their territories. Of particular importance here is that African states—relying on their ICC domestic legislationhave acted, or have been asked to act by victims and civil society groups, to investigate crimes committed by nationals of, or in the territory of, non-states parties. Such interventions present the potential for a ‘gap-closing’ form of complementary domestic action, whereby African states parties pursue the common goal of reducing impunity for grave crimes in circumstances where the ICC has been unable to do so because its lacks jurisdiction, or because the international politics within the UN Security Council have resulted in cases not being sent to the ICC. For example, a Palestinian group sought the arrest of the former minister of foreign affairs of Israel, Tzipi Livni, in South Africa under that country’s ICC legislation for Israeli atrocities in ‘Operation Cast Lead’ Livni ultimately chose not to visit South Africa.

There is thus an essential supporting role for states to play in pursuing justice in respect of nationals of non-states parties or crimes committed on their territories, which is particularly relevant where the ICC is unable or unwilling to exercise jurisdiction. It is at those moments, in an inversion of our ordinary understanding of complementarity, that national justice systems become the courts of last resort, the means by which to close the gaps left by the UN Security Council or the ICC, and no doubt a potential leveler of the currently uneven playing field in international criminal justice.

AN AFRICAN SUBSTITUTE FOR THE ICC? Some observers wonder whether the African Union [is] trying to undermine the ICC by establishing its own court or mechanism to try international crimes. In response to an AU decision in 2009 on whether to create an African substitute for the ICC, the AU Commission began a process in February 2010 to amend the protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights to expand the court’s jurisdiction to include international and transnational crimes. The resultant draft protocol adds criminal jurisdiction over the international crimes of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, as well as several transnational crimes such as terrorism, piracy, and corruption.

By May 2012, African government legal experts, ministers of justice and attorneys general had considered and adopted the draft protocol (except Article 28E relating to the crime of unconstitutional change of government, which presents definitional problems that require more attention). All that now remains is for the AU Assembly to formally adopt the draft protocol.

It would be incorrect to assume that the genesis of the current process to create an international criminal jurisdiction for the African court lies exclusively in the contemporary debates about Africa’s relationship with the ICC. This process actually began before the issuance of an arrest warrant against President Bashir in 2009. This is not to deny that he has benefitted from this process, in the sense that, ultimately, African states’ reservations about international criminal justice generally have been conflated with the desire to invest their own regional court with competence over international crimes.

The establishment of an international criminal court to try the crime of apartheid arose during the discussions on the adoption of the International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid in the early 1970s, a proposal that was not taken up. In 1980, when the draft African Charter on Human and People’s Rights was being discussed, the government of Guinea proposed the establishment of a court to try violations of human rights and other international crimes. This proposal was rejected, mainly because it was decided to establish a human rights commission rather than a human rights court. So the idea of an international criminal court or tribunal of some kind in Africa pre-dates the establishment of the ICC or the indictment of the Bashir.

In its current form, the earliest suggestion for an international criminal jurisdiction for the African court was made by a group of (African) experts, commissioned by the AU to advise it on the ‘merger’ of the African Court on Human and People’s Rights with the Court of Justice of the AU in 2004. Initially the recommendation was not widely supported within the AU. But the situation has evolved.

Three points help explain this. First, the emerging discourses within the AU on the perceived abuse of the principle of universal jurisdiction by courts in some European countries targeting high-level African officials and politicians. Both the Assembly of Heads of state of the AU and the Pan African Parliament decried this emerging trend. Upon a decision of the assembly, the AU formally initiated a dialogue on the issue with the European Union, which resulted in the establishment of the Ad Hoc AU-EU Expert Group on the Principle of Universal Jurisdiction in January 2009. One of the recommendations of the group was to examine the possibility and implications of giving the African court jurisdiction over genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Meanwhile, in its decision in this regard adopted in February 2009, the AU Assembly, in part, requested the

[AU] Commission, in consultation with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, to examine the implications of the Court being empowered to try international crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, and report thereon to the Assembly in 2010.

The second factor is the challenge faced by the AU over Senegal’s repeatedly stalled efforts to prosecute the former president of Chad, Hissène Habré. AU member states have for a long time now been frustrated with the slow pace of the proposed trial of Habré, in Senegal, under the principle of universal jurisdiction. They thus resolved to empower the African court so that, in similar future instances, the AU could refer such matters to its own competent court, rather than to the national courts of individual member states.

Third, there was a need to give effect to Article 25(5) of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, which requires the AU to formulate a novel international crime of ‘unconstitutional change of government.’ Article 25(5) requires the AU to formulate this new international crime and that it be tried at the African Court of Justice. For this reason, the jurisdiction to try this (and other) crimes was proposed for the proposed merged African Court of Justice and Human Rights, with the expansion of its jurisdiction to include international crimes.

There are, no doubt, some countries and leaders in Africa who support the proposal for an African criminal court or mechanism precisely to undermine the ICC, or because they hope it will replace the ICC. And the current accusations of selective justice and alleged regional, ethnic or regional bias by the ICC against Africa have animated the current debate regarding this proposal. But to the extent that the idea of establishing a court or mechanism within Africa to try certain types of serious international crimes predates the establishment of the ICC, it is too simplistic to claim that the proposal for such a mechanism is simply or purely motivated by a desire to undermine the ICC. At least that was not the original intent. And overtly, there has never been a discussion in the AU on the need to create a regional mechanism precisely for the purpose of undermining or supplanting the ICC as such.

Given the continent’s record of human rights atrocities, some have argued that vesting the African court with international criminal jurisdiction is a worthy development to end impunity. In principle, that is a laudable goal, but is it likely in practice, and at what cost?

The first issue is the drafting process. On paper this process has taken three years, but in reality government legal experts had just over one year to properly consider the draft protocol. Civil society and external legal experts were given little opportunity to comment; and the draft protocol was never made available on the AU’s website, or publicly posted for comment in other media. The AU would have benefitted from a broader process of consultation since questions about jurisdiction, the definition of crimes, immunities, institutional design and the practicalities of administration and enforcement, as well as the impact on domestic laws and obligations, require careful examination.

The second concern is with the African court’s ambitious jurisdictional reach. Legitimate questions can be asked about the court’s capacity to fulfil not only its newfound international criminal law obligations, but also about the effect that such stretching will have on its ability to deal with its general (existing) and human rights obligations. The subject matter of the court’s proposed criminal jurisdiction means it is expected not only to try the established international crimes, but also various other social issues that affect some African countries. A related difficulty involves funding. To ensure that justice can be done to the court’s wide jurisdiction, a vast amount of money will be required to ensure proper staffing and capacity to run international criminal trials, as well as to perform the court’s existing administrative tasks and to act as the continent’s regional human rights court.

The fiscal implications of vesting the court with criminal jurisdiction raise serious questions about the effectiveness, independence and impartiality of such a court—and the motive for rushing the international criminal chamber into existence. By way of example, the ICC’s budget—currently for investigating just three crimes, and not the range of offences the African court is expected to tackle—is more than 14 times that of the African court without a criminal component; and is just about double the entire budget of the AU.

Finally, given that the African court will be occupying the same legal universe as the ICC, it is necessary to consider the relationship (if any) between these two courts. Thirty-four African states are now parties to the ICC, and at least six of them have adopted implementing legislation to give effect to their obligations to it. It thus seems imperative that the relationship between the ICC and the African court be addressed. In the first place, which court will have primacy? Careful thought would also have to be given to the question of domestic legislation to enable a relationship with the expanded African court (especially around the issues of mutual legal assistance and extradition). Given these difficulties, it is surprising that the draft protocol nowhere mentions the ICC, let alone attempts to set a path for African states that must navigate the relationship between these two institutions. A useful comparison here is the careful thinking that has gone into drafting the proposed International Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Humanity, which similarly would envisage a new system for the prosecution of such crimes as a complement to the ICC’s Rome Statute.

LOOKING AHEAD: The cumulative language of various AU Assembly decisions going back to 2009 (all of which were specifically reaffirmed in the May 2013 decision) clearly suggests that the organization is becoming more stuck in its belief that the ICC process is ‘selective’, ‘skewed’, ‘biased’, and even ‘condescending’, towards Africa and that international justice must be conducted in a transparent and fair manner, in order to avoid any perception of double standards, and in conformity with the principles of international law. Moreover, official statements by the representatives of the organization (the current chair of the AU, the prime minister of Ethiopia, and the AU commissioner for peace and security) contain serious charges that the ICC is targeting Africans and engaging in ‘race hunting’. During the summit itself, some leaders reportedly expressed the view that, despite its name, the ICC has ceased to be ‘international’ and has become a ‘Western court targeting Africans’.

These strong sentiments echo the words of former AU Commission chairperson, Jean Ping, who suggested to journalists, at the AU summit in 2009, that the court is a ‘neocolonial plaything’ and that ‘Africa has been a place to experiment with their ideas.’ He accused the ICC of ignoring crimes in other parts of the world: ‘Why Africa only? Why were these laws not applied on Israel, Sri Lanka and Chechnya and [its] application is confined to Africa?’

The perception of ICC bias against Africa and lack of consistency and fairness in the way the court is implementing international criminal justice may not correspond with the true reality, but it cannot be wished away by simply being ignored. There are real issues and concerns on both sides that need to be addressed in a serious, constructive and cooperative manner through honest dialogue. The tendency by some on the AU side to paint the ICC as a tool of Western imperialism and as a neocolonial project out to get Africa is misplaced and undermines the genuine support and commitment that almost two-thirds of the AU member states have demonstrated by ratifying the Rome Statute.

At the same time, the temptation by the ICC itself and some of its supporters to dismiss without any serious consideration the complaints from the AU are equally misguided. Unfortunately, the animus directed towards the court by the AU is partly inspired by the UN Security Council ignoring its request to consider deferring the Bashir indictment. Of course the ICC should not be blamed for the inability or reluctance of the Security Council to listen to African voices (legitimate or not), but in the political universe that is the AU these nuances may be altogether lost. At the very least, this should also spur the court, in its own interests, to ask some difficult questions about its relationship with the Security Council. So, until there is a drastic change of heart on both sides, any change in the AU’s decisions on non-cooperation with the ICC is unlikely.

As to whether the AU will reverse its decision and allow the ICC to open a liaison office in Addis Ababa, this can best be answered by the relevant officials at the AU Commission and the ICC Secretariat. A source close to the AU Commission, expressing a personal view, has expressed serious doubt that this will ever happen. In this respect, it may be recalled that the issue of the liaison office had been discussed among the African states parties to the ICC on the margins of the Kampala Review Conference in May 2010, and again by the AU summit, also in Kampala, in July 2010. It appears opinion had been divided: some had sought to persuade the member states not to put the issue on the agenda of meetings, believing that it should be a matter for diplomatic negotiations between the AU Commission and the ICC Secretariat rather than a matter for political debate by member states. Others insisted that the matter be placed on the agenda for discussion involving both ICC states parties and non-parties, since the proposed liaison office would be accredited to the AU as a whole.

Given the political environment that had arisen following the Bashir indictment, and the decision on non-cooperation with the ICC that had been adopted at the previous summit in July 2009 in Libya, the cautious camp feared that a debate in the assembly would almost certainly result in a decision to reject the proposal to open a liaison office. Part of the argument was that the fact that the ICC was not seeking to open similar offices in other parts of the world but was determined to open one in Addis Ababa was itself evidence of the alleged targeting of Africa. In the circumstances, the matter was put on the agenda of the summit and the proposal was rejected by the assembly. Decision Assembly/AU/Dec.296(XV), para. 8 states that the Assembly ‘Decides to reject for now, the request by ICC to open a liaison office to the AU in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and requests the Commission to inform the ICC accordingly’.

It would require the assembly to adopt a new decision reversing itself on this matter. In the aftermath of the May 2013 decision discussed above, it is unlikely that this would happen any time soon. In fact, at the ICC ASP meeting in 2011 it was confirmed that the funds that the ICC had allocated for the liaison office in Addis Ababa had been removed from the ICC budget and allocated to other activities. This would seem to be an acknowledgement by the ICC itself that its efforts to open the liaison office have, for now, been unsuccessful. It would be going too far to say that the situation will never change. But it may take a long, long time.

CONCLUSION: The future of Africa’s relationship with the ICC is uncertain. Some African governments have a history of manipulating the ICC for their own political advantage—skillfully in some instances, as recently demonstrated by Kenya. And when their obligations under the Rome Statute conflict with their obligations to the AU, historically, too few African governments have lived up to the former. But the picture is not entirely bleak. While the expansion of the African Court’s jurisdiction to criminal matters has been interpreted as an attempt to undermine the ICC there could be a valid role for the African Court, given the right political and financial support. There is also a valid role for domestic prosecutions in international criminal justice. Meanwhile, there is encouraging evidence that calls for domestic action by civil society organizations are being increasingly listened to.

The AU Assembly’s request to the AU Commission to consider whether it would be possible to request an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the question of immunity can also be viewed in a positive light to the extent that it demonstrates the AU’s desire to oppose the ICC through legal channels where possible. Moreover, it can only be hoped that, perhaps, the brain-storming session on international criminal justice and Africa’s role in the ICC process requested by the Assembly in its May 2013 decision will lead to a better understanding and a more constructive dialogue between the various stakeholders, in particular the AU and the ICC.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Dr Max du Plessis is a barrister in South Africa and associate member of Doughty Street Chambers, London. In addition to his practice he is a senior research associate at the International Crime in Africa Program, Institute for Security Studies, Pretoria, and Associate Professor, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban.

Dr Max du Plessis is a barrister in South Africa and associate member of Doughty Street Chambers, London. In addition to his practice he is a senior research associate at the International Crime in Africa Program, Institute for Security Studies, Pretoria, and Associate Professor, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban.

Dr Tiyanjana Maluwa holds the H. Laddie Montague Chair in Law and is Associate Dean for International Affairs at the Dickinson School of Law, Pennsylvania State University. In addition, he is concurrently Director of the School of International Affairs at the same university. He previously served as legal adviser to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and as legal counsel to the Organization of African Unity.

Dr Tiyanjana Maluwa holds the H. Laddie Montague Chair in Law and is Associate Dean for International Affairs at the Dickinson School of Law, Pennsylvania State University. In addition, he is concurrently Director of the School of International Affairs at the same university. He previously served as legal adviser to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and as legal counsel to the Organization of African Unity.

Annie O’Reilly holds a JD from DePaul University College of Law and a BA from Trinity College, Dublin. She currently acts as Legal Adviser to the UN Special Rapporteur on Counter-Terrorism’s inquiry into the use of drones in counter-terrorism. She previously worked for the defense at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.

Annie O’Reilly holds a JD from DePaul University College of Law and a BA from Trinity College, Dublin. She currently acts as Legal Adviser to the UN Special Rapporteur on Counter-Terrorism’s inquiry into the use of drones in counter-terrorism. She previously worked for the defense at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.