PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

In December, a handful of middle-aged American immigrants attempted to topple the autocratic ruler of the Gambia. They had few weapons and an amateurish plan. What possessed them to risk everything in a mission that was doomed to fail?

fter the coup failed, the raids began. On New Year’s Day this year, FBI agents descended on a blue split-level house in a suburb of Minneapolis, Minnesota. In the dead of night, near Austin, Texas, they searched a million-dollar lakeside villa. Agents interrogated an activist at his house in the working-class town of Jonesboro, Georgia. At a rundown townhouse development in Lexington, Kentucky, they found the wife of a US soldier, with a refrigerator full of her husband’s favourite Gambian delicacies – dishes prepared for a triumphant homecoming and repurposed for mourning.

When the employees of Songhai Development, an Austin building firm, arrived at work on Monday 5 January, they discovered the FBI had visited their offices over the weekend and seized all the company’s computers. The company’s owner, Cherno Njie, was spending the holidays in west Africa. But Doug Hayes, who managed construction for Njie, expected his boss back at any moment – they had an apartment project that was about to face an important zoning commission hearing.

“I guess he really had a two-track mind,” Hayes said in May, with a rueful laugh, over lunch at his favourite Texas barbecue joint. “He had that going, and he also wanted to be president of the Gambia.”

By the end of that Monday, Njie’s name was all over the international news. He had been arrested as he got off a plane at Dulles international airport near Washington DC, and charged with organising a failed attempt to overthrow Yahya Jammeh, the military ruler of the Gambia, a slender riverine nation of fewer than 2 million people. One alleged co-conspirator, a Gambian who had served with the US army, had already confessed to US investigators, telling them he was one of a small group of men from the diaspora who had taken part in a botched nighttime attack in December on Jammeh’s residence.

The outcome was disastrous, both for the men involved and for the long-suffering citizens of the Gambia. But back in America, it played as a weird, farcical tale. “Meet The Man Who Wanted To Rule The Gambia”, read the headline on a Buzzfeed news story, above a photo from Njie’s LinkedIn profile. The alleged coup plotters were middle-aged immigrants, who had made good lives for themselves in America over the course of decades, with careers, wives, children, savings, suburban houses, citizenship – the whole archetypal dream. They only visited the Gambia occasionally, if at all, and they had little connection to politics in their homeland. What could have possessed them to risk everything in a foolhardy attempt to topple one of the world’s strangest dictators?

Jammeh is a tyrant out of caricature, a throwback to the African strongmen of the 1970s. He’s boasted that he will rule for “a billion years”. He’s adopted a ridiculous string of titles: “His Excellency Sheikh Professor Alhaji Dr Yahya AJJ Jammeh Babili Mansa.” (The last phrase translates to “conqueror of rivers”.) He’s posed as a fetishistic healer, claiming magical powers to cure Aids, asthma and diabetes, and has launched witch-hunts to root out enemy sorcerers. He’s deployed demagoguery against human rights groups, fanning popular hatred of gays, whom he has threatened to behead. He’s massacred protesters and disappeared political opponents. Through his feared intelligence service, he exercises crushing power over every aspect of the Gambia’s politics and economy, which subsists mainly on income from discount tourism and peanuts.

The Gambia Freedom League, as the would-be liberators called themselves, sought to oust Jammeh with about a dozen fighters and small arms they had smuggled into the country. They didn’t get very far. When they charged at the presidential mansion, expecting support from covert allies inside, they were met instead with a volley of bullets. At least four were killed. Criminal complaints subsequently filed by US federal prosecutors underscored the ironic distance between the aims of the commando plan and its amateurish execution. Some conspirators knew each other only by code names like “X” and “Fox”. Documents were kept in a manila folder marked “Top Secret”. Njie, identified as the leader and financier, allegedly possessed a spreadsheet budgeting for equipment such as sniper rifles (“NOT really necessary but could be very useful”), along with a manifesto titled Gambia Reborn: A Charter for Transition from Dictatorship to Democracy and Development.

In Texas, where Njie was a well-known player in the business of building government-subsidised housing for the poor, the news met with astonishment. “I mean, Cherno was going to overthrow a government?” said Don Bethel, an estate agent who previously served as the chairman of the board overseeing the state housing department. “It’s serious for him, but you kind of laugh – good gosh!”

“I think he got caught up in delusions of grandeur,” Hayes said. “Even if you’re successful …. Congratulations, now you’re the president of the Gambia.”

There was one place, though, where the overthrow attempt made perfect sense, and its failure was lamented as a tragedy – where the conspirators were not derided as bunglers, but lauded as freedom fighters. That place was Facebook. The Gambia’s overseas diaspora amounts to maybe 70,000 people worldwide, and the Census Bureau estimates that only around 11,000 live in the United States. But what the diaspora lacks in numbers, it makes up for in organisation and the volume of its dissent, which rings across social networks and tinny internet radio stations. As soon as gunshots broke out in Banjul, the Gambia’s capital, the diaspora’s online forums filled with rumours and rejoicing. When the coup was foiled, the community posted prayers, poems and bellicose tributes, including a video dedicated to the fallen, linked by a Facebook user who goes by the name Gambian Sniper.

“It is Yahya Jammeh who is responsible for THIS FIGHT and YES … FIGHT IS WHAT YOU HAVE ON YOUR HANDS Yahya Jammeh,” read another widely circulated post, by a Gambian activist living in Seattle. “While we celebrate the lives of our gallant citizens who took the fight to your doorsteps, we are regrouping, resharpening our pens, reorganising for the next phase.”

Since January, that fight has largely been focused on a court case in Minnesota, where federal prosecutors have charged five Gambians with violating the Neutrality Act, a seldom-invoked 1794 law that makes it illegal to mount a military expedition against “any foreign prince or state” with whom the US is at peace. It is not difficult to see why the American government would be interested in discouraging citizens from attempting freelance regime change. But the diaspora has rallied to the defence of its “truly courageous and patriotic sons”, as one crowdfunding campaign called them – organising events like a protest in front of the Justice Department in Washington against the “tyrant appeasing charges”.

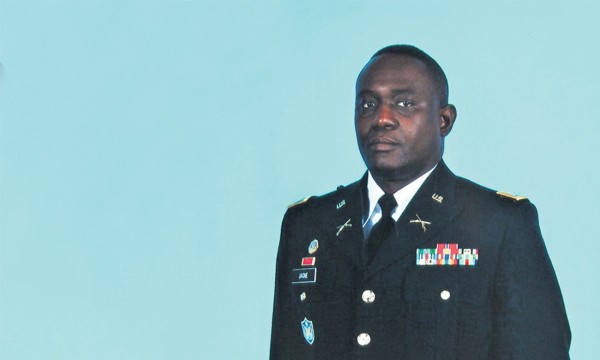

The coup attempt has focused attention on an obscure corner of US foreign policy, demonstrating the lengths to which America will go to maintain stable relations in volatile west Africa – even if it means occasionally mollifying a cruel and autocratic buffoon. And while much of the prosecution’s evidence is still obscured by secrecy, the case has already revealed much about the ideals and motivations of the men who sought to topple Jammeh, who regarded their fight as a struggle for democratic values. Some of them had served as soldiers in American wars abroad. The key mobiliser, Njaga Jagne, was a veteran officer who did two tours in Iraq.

The coup plot, years in the making, was not the work of a single mastermind, but rather a collaborative effort that germinated within the activist ecosystem. The same technological tools that facilitated democratic speech and debate also allowed a hardcore handful to rally around a radical idea: that words were no longer sufficient, and violent change was possible. They saw themselves as Americans, pursuing American ideals, with American guns. Some now face prison sentences. Others paid a higher price.

* * *

In April, a week before the Kentucky Derby was run, I visited the state to see where the Gambian coup was born. Captain Njaga Jagne immigrated to the US in 1994; he did not see his homeland again until he returned to overthrow the government. For much of the intervening time, he lived in Kentucky’s state capital, Frankfort, a quaint little town surrounded by horse farms and bourbon distilleries. Jagne’s sister Sigga, a public health expert, still lives there with their elderly mother, beside a creek, in a house that is filled with African art.

“When he got into the military I tried to dissuade him,” Sigga told me as she sifted through a box of old photos. There was a picture of Njaga from his university days, wearing a backwards baseball cap and a leather jacket, and a later one from basic training, where he was grinning and carrying an assault rifle. “I was like, ‘You have a degree. Why are you going into the war?’” Hanging on the wall above us, inside a triangular frame, was a folded US flag. Sigga, a lithe woman in her early 40s, pulled the frame down; it was affixed with a brass plate that read: “AMERICAN SOLDIER.”

Njaga, her elder brother, was born in 1971, six years after the Gambia gained independence from Britain. Originally colonised as a slave trading outpost at the edge of the Mali empire, it stood apart in its placidity. Its people, mostly Muslims, coexisted harmoniously. Journalist David Lamb, in his 1983 book The Africans, called the Gambia “a pleasing little West African country that lives by its wits and within its means.” At that time, the army numbered around 500 soldiers. Sir Dawda Jawara, the first and only president, dominated regular (if flawed) elections. The Jagne family was not wealthy – their mother made money by peddling hot lunches – but their father was a principal of the Gambia’s oldest boarding school, and had good connections. “He had educated a lot of the people who became the first leaders of the country,” Sigga said. After high school, both Njaga and Sigga managed to secure US student visas that allowed them to continue their studies at Kentucky State University, under the auspices of a scholarship programme run by a political scientist who had worked in the Gambia.

In provincial Frankfort, the Jagne siblings made an unusual pair: Sigga was a striking spitfire, Njaga reserved but physically imposing, an intimidating defender on the football pitch. He lived with a small group of international students in a building owned by a Methodist campus ministry. The residents engaged in spirited political arguments, teasing each other about their national identities, and would drive to nearby Louisville for dance parties at an African restaurant. Njaga graduated with a degree in criminal justice, and took a job at a fast-food cafe. “That’s Frankfort life,” said Kumar Rashad, a school friend who also worked there. “Factories and restaurants.” He began a relationship with his older American manager, ignoring the stares the interracial pairing sometimes drew. “Njaga was a real true man,” Rashad said. “He stood proud.”

Rashad says his friend would rhapsodise about his life at home: the tropical beaches, the palms, the easygoing lifestyle. But Njaga’s connection to his country had been severed by tumultuous events. Jawara’s regime had become corrupt and unpopular, and in 1994, the same year Njaga left, a cabal of mid-level army officers took power, almost without firing a shot. Captain Yahya Jammeh emerged as the junta’s leader. As a populist and a member of a low-status ethnic group, Jammeh was able to harness resentment against the old elite. He promised roads and schools, and to some degree, he delivered. But he was predictably repressive.

In 2000, Jagne’s younger half-brother Assan participated in a street protest in Banjul, sparked by the torture and killing of a fellow student. At the personal command of Jammeh’s interior minister, security forces opened fire. Assan was shot in the back as he fled. He lay in the street, thinking he would bleed to death, until a pair of passing men loaded him into a car, over threats from a soldier. They rushed him to the hospital, barely alive. “For me, that was the turning point, because I could not believe that in the Gambia I knew, in broad daylight, students were basically slaughtered,” Sigga said.

Assan had serious wounds to his stomach, and Sigga – who by now was working in public health for the Kentucky state government – threw herself into ensuring that he and other injured protesters received adequate care. “These young men, these brave 10 or 11 survivors, got me into advocacy,” she said. She mounted a fundraising campaign and pressured the Gambian government to allow the protesters to be treated overseas, and later helped to found a diaspora opposition group called the Save the Gambia Democracy Project. Njaga was equally shaken, but responded differently. Shortly after the massacre, he wrote a venomous post on a Gambian listserv:

“YAYA……….!!!!!!!!!!!! … WITH IMMEDIATE EFFECT DISMISS ALL YOUR IDIOTS, HYPOCRATS [sic], YOUR INCOMPETENT CABINET, AND ALL YOUR ASS-LICKERS. RETIRE YOURSELF, THEN COMMIT SUICIDE.”

At the time, Njaga was preparing to start a master’s degree in Mississippi. But he dropped out after only a few months. “I have been walking around like a zombie,” he explained in an anguished message to his brother. “I wanted to give you all the things I never had. I wanted you to never worry about all those things I had to go through. Our problem today, however, is much bigger than I could have ever imagined. Anything that I had ever done or would do is hopelessly inadequate.” Assan eventually joined his family in Kentucky. Njaga also moved back to Frankfort, and went through an unsettled period. He worked fast-food jobs, married and quickly divorced, then struggled through chaotic relationships that gave him two sons by different mothers. At some point, though, he found a way forward.

From Sigga’s house, I drove west to the city of Lexington to see Assan, a tall soft-spoken young man who works at an Amazon distribution facility. “He loved the values of the military,” he said of his brother. “Responsibility, discipline, defending the helpless.”

In 2005, at the age of 34, Njaga enlisted in the Kentucky National Guard. The guard is a state militia, but it trains like the regular army, and its units can be called up for active duty overseas. When Njaga joined, the US military – overstretched as it fought two wars simultaneously – was mobilising every soldier it could. The recruits shipped out for basic training, knowing they would soon be heading to Iraq. “I just wish that I had done this 5/10 years ago,” Njaga wrote home to his sister. He lost 25 pounds as he tried to keep up with younger men, and dreamed of feasting on benachin and mbahal, Gambian rice dishes. His mother sent him an amulet containing a verse from the Koran, meant to protect him from harm. In June 2006, he sent home a postcard: “Greetings from the Green Zone.” It was the most dismal period of the war, the year before the “surge”, and Sigga wrote an email begging her brother to think of his sons: “Do not sacrifice yourself for any reason.”

“The US is our home and no matter where we are from and who we are, we are not exempt from the desires of extremists to eliminate us,” Njaga responded. “I will gladly lay down my life to help in any way ensure that my children and all my relatives in and out of the US continue to enjoy the freedoms they do.”

During his tour, Njaga became a US citizen. At the ceremony, he was congratulated by the commanding general of the forces in Iraq. His experience seems to have been otherwise uneventful. He broke his leg playing basketball, and spent much of his time sitting on guard duty on a fortified base in Baghdad. Nonetheless, when he came home he was changed. He had found his place. When he went off active duty, he worked for the military in various support roles, including one with a programme that helped veterans reintegrate into family life. But he was eager to return to war.

“He believed wholeheartedly that they were going there for the right reasons,” Sigga said. “They were doing something honourable, it was that they were getting rid of evil.”

Meanwhile, however, the US was doing little to get rid of Jammeh, who only grew more dictatorial after the student massacre. Classified State Department cables published by WikiLeaks, running from 2006 to 2010, reveal a consistent US concern about Jammeh’s “penchant for erratic and sometimes bizarre behaviour”, and an awareness of the brutal measures he employed against real and perceived opponents. Yet the communications suggest a willingness to look past his abusive practices for reasons of national interest. Jammeh assisted in at least one CIA rendition during the Bush administration. The cables referred obliquely to “specific bilateral [counterterrorism] efforts”, as well as unspecified “US aid to the NIA”, Jammeh’s intelligence service. Jammeh assured US diplomats that he was committed to assisting the fight against drug trafficking, though suspicions abound that the regime has profited from the trade.

Njaga left Iraq as the war came to its official end. But he was already beginning to devise another mission. “Njaga spoke to me once, five years ago, that he had plans to go to Gambia and get this guy out of office,” said his half-brother Andala, who lives in Phoenix. He sounded like he was just venting, but his actions look concerted in retrospect, Andala said. “His brother got shot, and that’s where everything started.”

“He is not a reckless person – pretty much everything he does, he thinks about it,” Assan said. “When this happened, I asked myself how much what had happened to me had to do with what he eventually did. It probably did contribute. How much? I’m not sure.”

* * *

Political movements are viral, but conspiracies are bacterial. They thrive in dark recesses, fed by self-reinforcement, shielded from the disinfecting light of contrary opinion. The Gambian coup plotters confided their intentions to very few, and were especially careful to conceal their activities from those who were closest. Documents filed by prosecutors reveal some of the evidence uncovered in the FBI’s searches of the plotters’ houses and computers, including an operational plan, receipts from gun stores for assault weapons – this is America, after all – and a primer by a former SAS soldier entitled How to Stage a Military Coup. But they don’t answer the perplexing question the men’s friends and families keep asking: What on earth were they thinking?

The best evidence of Cherno Njie’s intentions comes from his manifesto, Gambia Reborn. In majestic language, its preamble lays out the justification for revolutionary action.“Having foreclosed all avenues of peaceful opposition, President Jammeh, as repressive as he is incorrigible, is leading the country on an inexorable downward spiral,” it read. “The regime has lost all claim to legitimacy and the only recourse available to Gambians is to mount a campaign to remove the dictatorship and salvage the country. It is to this task that the Gambia Freedom League has dedicated itself.”

“I just don’t know how a group of 10 people can sit down and think they can overthrow a government,” said Toyin Falola, a history professor at the University of Texas and one of Cherno Njie’s closest friends in Austin. We were sitting at his marble kitchen table, carved in the shape of Africa, where he Njie had often discussed politics over dinner. “Before he puts food in his mouth,” Falola told me, “he always says, ‘God bless America’.”

While the Jagne family assimilated through education and military service, Njie took another reliable route to becoming an American: he got rich. His success was built on an understanding of how government works in his adopted country. In the early 1980s, Njie moved to the US to attend the University of Texas in Austin, a cosmopolitan oasis in the heart of aridly conservative Texas. He studied politics and planning, and ended up as a bureaucrat at the state’s housing department. In the 1990s, the era of governor George W Bush, the department vastly expanded a programme that incentivised the construction of affordable housing via tax credits to the private sector, a policy favoured by Republicans and developers. “It was a philosophical position,” said Harryette Ehrhardt, a Democratic state legislator at the time. “Although I suspect it was also very lucrative for them.”

Each year, the department would allocate credits worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Critics claimed that in practice, the agency steered money to favoured developers. “The whole department was riddled, just riddled, with corruption,” said Ehrhardt, who campaigned to reform it. Bush’s first appointee to run the agency, a bluff Texas banker, resigned amid an investigation into shady real estate dealings. A board member was later indicted for taking bribes in return for her vote on tax credit deals. While awaiting trial, she continued to attend board meetings accompanied by a pair of armed bodyguards, claiming she feared assassination. (She was ultimately convicted and served time in federal prison.) During this time period, Njie had a great deal of funding power as the official in charge of the arcane process of awarding tax breaks.

“There were a lot of eyeballs on him,” said Kent Conine, a homebuilder who was on the agency’s board at the time. Although Njie was never implicated in any of the criminal investigations, some developers complained that he had given preferential treatment to a handful of African-born bidders. One of them, a Dallas-based builder named Jay Oji, told me he befriended Njie after his 1991 marriage to a fellow Nigerian, and had accompanied him on a trip there to meet her family. “Cherno was a very sharp, very intelligent, very smart guy,” Oji said.

Housing agency insiders often quit and became developers themselves. When Njie left, in 2001, he founded a company called Songhai Development, named after an ancient African empire. A major developer who was one of the largest tax credit beneficiaries during Njie’s tenure immediately put him on a $5,000-a-month retainer. (The relationship ended in litigation, and a few years later the big developer went to prison for bribing Dallas city officials.) Njie went on to develop four projects around the state. He was a relatively small player, with only a handful of staff, but with each deal he reaped millions in development fees.

“He knew how to play the game,” said Doug Hayes. “It’s very political.”

Songhai’s highest-profile project was in the affluent – and predominantly white – town of Frisco, outside Dallas. It was proposed as a model by an advocacy group called the Inclusive Communities Project, which had sued the state over its rubric for issuing tax credits, arguing that it tended to concentrate affordable housing in poor black neighbourhoods. The project met stiff resistance. The city council employed delay tactics; protesters put up fear-mongering signs. One resident wrote to Njie to warn that “Baby Daddy’s [sic], relatives released from jail” and other undesirables would “cause havoc on the neighbourhood with drug sales and other crime.” Njie replied diplomatically to such complaints, and patiently worked to push the project through. “Cherno had no problem fighting that fight,” said Ann Lott, an Inclusive Communities Project executive. Last month, the organisation won a landmark housing discrimination ruling from the US supreme court. “Cherno contributed, in my opinion, to an important social good,” said John Henneberger, a Texas affordable housing advocate.

“You have to stand by your principle that, look, we’re not talking about aliens,” Njie said of the experience in a speech last year at a housing conference. “These are fellow citizens who demand nothing but access to equal opportunity.”

In his thick Gambian accent, Njie tended to express sentiments befitting a Texas real estate developer. He talked about his desire to build something in Africa, and to instil his homeland with entrepreneurial values. He favoured small-government solutions. He watched Fox News until late in the night. He sided with the police in civil rights disputes. He may be the only African who voted against Barack Obama in 2008. He sent his son to an exclusive private school and Rice University, in Houston. After he got wealthy, he and his second wife – a much younger Gambian – tried to build a 6,600 square-foot mansion on a scenic property in the moneyed West Lake Hills section of Austin. When neighbourhood protests over the gargantuan design blocked a necessary zoning variance, Njie instead bought a Mission-style villa in a gated community on Lake Travis.

Before he was identified as the leader of the coup, Njie was not a well-known figure in the Gambian diaspora. Still, one activist told me, Njie was not a complete stranger to the resistance. “He’s been in it quite a bit, but in the shadows,” he said. Njie gave some quiet sponsorship to online media, including two North Carolina-based online publications, the Gambia Echo and Freedom Newspaper. “He was a guy of great wealth,” said Dr Abdoulaye Saine, a Gambian professor at Miami University in Ohio who is active in the opposition to Jammeh. “I knew him mostly for talking about democratic processes and supporting democratic initiatives.”

Freedom Newspaper, especially, is an influential – if not entirely reliable – source of anti-Jammeh invective, delivered both in print and on its vociferous radio feed. Jammeh is said to follow Freedom closely; he complained about its “lies” in a 2010 meeting with the US ambassador, according to the WikiLeaks cables, which depict the dictator’s almost poignant concerns about his own image. “I want your government to know that I am not the monster you think I am,” Jammeh told the ambassador, who wrote in turn that he saw “an opportunity to build on our constructive relationship with this majority Muslim country that has shown willingness to cooperate with us”.

Jammeh’s crackdown on dissent only grew harsher. A former Gambian government minister who happened to be an American citizen was thrown in jail for distributing anti-Jammeh T-shirts. (He and another Gambian-American were eventually rescued through the intervention of the Rev Jesse Jackson.) At the end of Ramadan in 2012, Jammeh announced he would execute all Gambia’s death row prisoners, and carried out nine sentences. A prominent imam who spoke out against the death penalty was taken away by Jammeh’s thugs, imprisoned and tortured. That incident proved to be a decisive breaking point for many, including Njie.

“We discussed Jammeh a lot,” Falola said. “He hated the guy for the right reasons.” In May 2013, Njie attended a summit of Gambian activists in Raleigh, North Carolina. Billed as a “unity conference”, it attracted an alphabet soup of opposition groups for two days of discussion about human rights, elections, fundraising, and pressure tactics. There was open debate about military options, but ultimately, the delegates opted for a non-violent stance, voting on a charter called the Raleigh Accord. It created a new umbrella political organisation, the Committee for the Restoration of Democracy in the Gambia. Saine was elected its chairman, and Sigga Jagne, vice-chair.

Sigga met Njie at the conference. Afterwards, she introduced him to her brother.

* * *

Over the years, Sigga had devoted much of her time away from her job as head of Kentucky’s HIV prevention programmes to the Gambian struggle. She had participated in many events like the Raleigh unity conference, and they always ended the same way: with bold proclamations that did little to dislodge Jammeh from power. Though her brother attended the occasional protest, he had no time for the schismatic frustrations of exile politics. “He hated that side of it, and that is why he was not involved in the day-to-day advocacy,” Sigga said. “That is Njaga. He was not a talker.”

Njaga became a different person, though, once he got on Facebook. He was a vocal participant in a 30,000-member Gambian political forum started by his high school classmate Banka Manneh, an Atlanta-based civil society advocate who worked with Sigga on many projects, including the unity conference. Njaga would sometimes tease Manneh about his peaceful approach, asking him if he thought Jammeh was taking heed of his communiques and protests. “We have to find a way,” Njaga wrote in the forum in late 2013, “to fight for ourselves and restore democracy and sanity, without dancing with any devils.” He would wage war in the comments against anyone who criticised America, promoted sharia or fundamentalism, or dared to defend Jammeh:

“You’ve got enough rope to hang yourself. Please just go ahead and spare us the trouble. While you are at it, can you also drag along the abomination Yahya Jammeh to hell with you? Please!!? … This guy is the complete definition of an idiot. He is a lost soul. Like a cockroach, he keeps resurfacing. … You are an enabler, promoter, and participant to the ineptitude, injustice, and horrors of Jammeh’s regime. You should look into democracy. It’s actually pretty good. You just might like it.”

“A bunch of people have been sitting on their grievances,” Manneh told me. “When you have people converging on a place like that, then obviously, folks will begin to feel each other’s pulse and reach out to each other.” Through Facebook, Njaga met a young Gambian woman from Seattle, who was different from the more cautious activists of his generation. She went by the nom de guerre Mprez, and for a time co-hosted an internet radio show called GamSocial. She had a fiery temperament. In a YouTube clip from a protest, she paraphrased a Thomas Jefferson adage beloved by American radicals – “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants” – and declared: “Yahya Jammeh has to go, by all means necessary at this point.” (She did not respond to several messages seeking comment.) Njaga’s friends and relatives say he fell in love from afar. After just a few weeks of phone calls, they were making plans to marry.

In October 2013, Njaga posted an “open letter” to Jammeh on Facebook. “You are receiving this message and will be receiving messages from me and others like me in the near future,” he wrote. He implied that a violent confrontation was coming. “For those who do wrong, heaven and earth will be moved and no stone will be left unturned to bring justice to their door. Again, no one else should have anything to fear.”

“I started getting worried when I read that,” Sigga said. “I know my brother. He doesn’t do anything half-assed.”

When Sigga asked about the post, though, Njaga assured her it was just rhetoric. After years of standing aloof, he was finally getting involved in her struggle. One evening that same month, Njaga visited his sister’s house. They discussed the idea of endowing a fund that could pay for political activities on an ongoing basis, instead of depending on ad hoc fundraising appeals. Njaga seemed impassioned, so Sigga suggested he get in touch with a wealthy Gambian who could help: Cherno Njie. She had kept in touch with him since the Raleigh conference a few months before, enlisting his backing for initiatives such as lobbying mission to the European Union in Brussels and a radio programme she and other activists planned to beam into Gambia from Senegal. “I called Cherno and said, ‘I want to introduce you to my brother,’” Sigga said.

By this time, the plot was already beginning to take shape. In 2013, the commander of Jammeh’s presidential guard, Colonel Lamin Sanneh, was ousted in one of the dictator’s frequent purges. Sanneh had recently completed a master’s degree at a Pentagon-funded school, so he fled back to Washington. He got in touch with Banka Manneh, saying he still had friends at high levels inside the Gambian military. After some convincing, Manneh put the officer in touch with his old friend Njaga, who was already thinking along similar lines. Njaga brought in his closest friend, Alagie Barrow, a former Tennessee national guardsman. They had first connected as fellow Gambians at officer candidate school, and later got to know one another better while playing Words with Friends online. Over time, their conversations had shifted from friendly banter to serious political talk, about their shared desire to do something about Yahya Jammeh.

One person Njaga didn’t tell about the developing plan, it seems clear, was his sister. In early 2014, Njaga married his Facebook paramour in a traditional Gambian ceremony in Seattle. Mprez then moved to Kentucky. The whirlwind relationship estranged Njaga from his immediate family. Sigga thought he was getting carried away – with Mprez, with Facebook, with internet liberation. “It’s not Facebook that caused it, but Facebook is the catalyst, it’s the delivery system for instant information,” she said. “Once he got engaged in it, every day there was something that was making him mad.”

In March 2014, Manneh threw out a topic for discussion on his forum: “Is military action a viable option? Me thinks, what do you?:)” Commenters were heavily in favour.

After some negotiation, Njaga convinced Njie to finance the plot. The developer felt the situation in the Gambia had become intolerable, and the possibility of cooperation from within Jammeh’s regime appealed to him. The coup looked like it could be a seamless transaction. The conspirators would talk on a conference call every other Saturday evening. By April, according to a federal indictment, Njie was sending out money for initial preparations, and the next month he and Manneh discussed leadership positions that would need to be filled in a transitional government. Although there seems to have been no firm understanding that Njie would be president, he was planning to manage the transition. His manifesto, written to be the “supreme legal instrument” of a caretaker government, set out a list of ministries, asserted “emergency powers” of detention for former regime leaders, and promised to respect human rights and “free market economic principles”.

The spreadsheet allegedly found during a search of Njie’s properties laid out a $220,000 budget, which included airfare for 20 personnel, stipends for two weeks to a month, and equipment such as guns and body armour. The men split up the purchasing – even Manneh, the civil society advocate, procured a rifle and two pistols. “John F Kennedy once said, ‘When you make peaceful revolution impossible you make violent revolution inevitable,’” Manneh told me. “That’s what you have in the Gambia, unfortunately.”

Njaga coordinated logistics, shipping equipment to Africa, concealed in barrels of used clothing. He also seems to have handled much of the recruiting. During this period, he travelled to Germany on official military duty, and while it’s uncertain what he did there, several Gambians living in Europe participated in the plot. He also called Papa Faal, another Gambian who had served in the US army in Afghanistan.

A grand-nephew of president Jawara, Faal had attended the Raleigh conference with Manneh and Njie, where he had openly voiced his support for military force. “There is no other choice than to force this guy out through the barrel of the gun,” Faal told me in a phone conversation from Minnesota, where he is under house arrest. He didn’t know Njaga or most of the other conspirators, but he looked at the operational plan the soldiers had drawn up, which resembled those he had seen in the army. “It seemed very detailed and professional,” Faal said. “That got me very impressed with the team.” The plan allegedly anticipated that around 160 Gambian soldiers loyal to Sanneh would join them. Faal said some of these supposed allies ultimately met with them in Banjul. “Sanneh and all the other Gambian soldiers who joined us always said, ‘No Gambian in the State House will fight for Yahya Jammeh,’” Faal told me.

The operation was supposed to be swift and bloodless. It was supposed to be such a cakewalk, in fact, that Faal brought his wife and young child along with him to the Gambia. His family expected to be with him for the holidays, and he couldn’t figure out a way to dissuade them without raising his wife’s suspicions. “With something like this,” Faal said, “if you tell them, they might try to talk you out of it.”

* * *

On the evening of 30 December, Sigga Jagne went to dinner with some friends. It was the end of an exhausting year – she had spent months in New York responding to the Ebola crisis – and they were just about to relax with a movie when she received a text message from a friend in the diaspora. There’s a coup in Gambia, are you listening to Freedom? Sigga used her phone to access a live web broadcast, but the situation was confusing. Freedom initially reported that army mutineers had taken control of the State House, as well as the airport, a strategic bridge and a notorious prison. But it also said that the leader of the coup, Colonel Lamin Sanneh, was dead.

Sigga knew that Njaga had travelled out of the country a few weeks before, but she had the impression he was going back to Germany. “He’s never been to Gambia since he came here,” she said. Now, however, she started hearing rumours. “All of a sudden, I’m getting information that, hey, your brother is involved,” Sigga said. “I’m like, OK, wait a minute how is my brother involved? And what is going on? But in the chaos of things I couldn’t really get clarity.” The next day, Freedom posted an update: “Breaking news: Two US residents killed during army mutiny in Gambia!!” The other casualty, the site reported, was Captain Njaga Jagne.

Amid the frantic uncertainty, Sigga called the US embassy in Banjul. “They were more focused on saying, ‘If your brother is involved, it was a crime,’” she said. That same day, Papa Faal walked into the US embassy in Dakar, the capital of neighbouring Senegal. He had managed to flee, but he was worried about the safety of his wife and child, who were still trying to get out of the Gambia. As a US citizen, he was expecting the embassy’s protection, but instead he was interrogated. He described how the plan went awry.

Most of the conspirators had arrived in the Gambia in early December. According to the Gambian media, Njaga and others operated out of a seaside luxury apartment complex. Njie joined them later in the month. All the men reportedly went by code names: Njie was “Dave,” Faal was “Fox”, Barrow was “X”, and Njaga was “Bandit”. In the end, only about half the expected number of men actually participated. The plotters wanted to ambush Jammeh’s convoy during his traditional holiday travels around the country, but then the president abruptly went on an overseas trip.

They suspected a leak, but Sanneh’s sources inside the presidential guard were still reassuring him. He argued that they could still depose the regime if they acted fast. Njaga sent a text message to his wife back in Kentucky, telling her to cook a celebratory dinner – he was about to return. On the night of 30 December, Njie allegedly retreated to a safe house while the other conspirators rendezvoused in some woods near the president’s residence to change into assault gear. One man failed to show up, taking with him one of their two pairs of night vision goggles. Nonetheless, Sanneh called his State House contacts to say he was coming. He and Njaga went with the team that approached the front door, while Faal went with the team taking the rear. The plan was for Njaga to fire his M4 rifle once in the air as a signal to their Gambian collaborators. But when the shot went up, the guards out front instead opened fire on him.

Afterwards, the survivors came to the bitter conclusion that they had been betrayed. But by whom? They blamed Sanneh’s moles. Some also wondered why Faal had turned himself in so quickly. But Faal told me that when he was flown back to the US and told his story to FBI agents, they indicated they had been aware of the plot all along. He claims that without prompting, they held up a picture of Njie, and asked: “Is this Dave?”

In May, the Washington Post reported that the FBI had visited Sanneh at his home in Maryland prior to his departure, asking why he had purchased a plane ticket to Dakar. The agency alerted the State Department, the Post reported, which in turn “secretly tipped off” an unnamed west African country – generally presumed to be Senegal – in the hope that it would intercept Sanneh. The coup plotters suspect that the information instead ended up in Jammeh’s hands. “When we, the people in prison right now, are going through this ordeal, Gambians are thinking: is the US hiding something?” Faal said. Later, after the Post story appeared, Faal added, “I would go so far as saying they killed Njaga. They are responsible for that.”

US prosecutors ultimately indicted Faal, Njie, Barrow and Manneh on conspiracy and weapons charges. (A fifth Gambian-American was also charged in a sealed indictment.) Diaspora activists were infuriated by the charges. “What is America’s interest with Yahya Jammeh?” asked Pa Moudou An, a former Gambian army officer who heads a Minnesota-based exile group. I met him in Washington in April, in front of the White House, for a rally commemorating the 15th anniversary of the student massacre that set Njaga on his path. Beneath pinkish rose blossoms, protesters jostled with demonstrators for other causes, shouting into a din of slogans: “Yahya Jammeh must go! Yahya Jammeh terrorist!”

Across the street was a hotel where, the year before, Jammeh had stayed before a White House meeting. The state visit had resulted in a photograph of the dictator, in white robes and carrying a ceremonial staff, posing with Barack and Michelle Obama. Jammeh immediately had the picture plastered on T-shirts back in Gambia. After the coup attempt, Jammeh blamed “western backed terrorists”, and began rounding up anyone connected to the attackers, including innocent family members. The State Department responded with conciliation. “We are not interested in regime change in the Gambia,” the highest-ranking US diplomat in the country recently told a local newspaper.

Since the coup, many Gambian democracy activists have been visited by the FBI. The diaspora media has reported many rumours about other co-conspirators, political figures who positioned themselves conveniently in Senegal before the coup. “Whether you know it or not,” one of them said when I reached him by phone back at home in the US, “the FBI is even listening to us as we talk.” There’s no longer much loose talk about violent revolt. After the protest, some two dozen Gambians, representing about as many exile organisations, gathered in Silver Spring for another summit. They ate well, gave speeches urging unity and democratic opposition, and then they dispersed.

After the coup, Sigga resigned from the Committee for the Restoration of Democracy in the Gambia. She told me she understood why her brother felt he had to take drastic action against Jammeh. “There was a growing feeling among Gambians that nothing short of forceful removal would take him out,” she said. Sigga was acquainted with almost all of the publicly identified participants in the coup plot, but she insists that she had no idea it was under way. When I asked if she wished she had known about the plot, she sighed.

“You know, it’s a hard thing,” she said. “I was saying to myself, I wish I had spoken to him more, had taken the time to really warn him, be that voice to say, hey, trust me.”

After a pause, Sigga went on. “To say OK, listen, do we all want Jammeh to get out? Yes. If I had the power militarily or otherwise to pluck him out today, would I do it? Yes. … Yes, you’re right, we’ve tried all these things. And he’s seen me put in so much of my money, my time, my effort, and a lot of talking and arguing and fighting, without it happening. But is there something else?”

At some point after she linked her brother to Cherno Njie, however, their insurgent talk had turned to action. Sigga was now left to bear the consequences: contending with Njaga’s widow and the settlement of his estate – a particularly complicated matter, because the US embassy hadn’t provided the documentation necessary for a death certificate. The surviving conspirators were dealing with prosecutors, who could potentially escalate the charges and ask a judge for long prison terms. To date, all the defendants have pleaded guilty except Njie. But no one expects him to go to trial. His wife gave birth to their second child while he was out on bail, living in a halfway house. His business has gone dormant, and he is trying to sell the Austin tract where he was planning his next project. Since January, his hair has turned completely white.

Sigga did not recieve confirmation of her brother’s death until a few days after the coup, when someone – presumably affiliated with Jammeh – sent her a picture of his corpse on Facebook. At first, she didn’t believe it. “What I saw was not the brother I knew,” she said. Sigga told me that the pictures were also sent to the editor of the Freedom Newspaper, who published them on the web. In our many hours of conversation about her brother’s death, it was the only moment that she cried.

Everyone in the family was worried about what would happen with Njaga’s sons, both around 10 – old enough to understand that their father was dead, if not why. Sigga was still having trouble with that question herself. How could her brother have put so much at risk? “It was just crazy!” she told me. “They should have thought it through. What if this fails?”

Like many Gambians, she wondered if the conspirators, in their secret fervour, had confused Jammeh as he appeared on Facebook – the cartoonish monster almost begging to be overthrown – with the real dictator, a brutally effective survivor. If Sigga felt one consolation, it was that because of her brother’s sacrifice, the rest of the world was now aware of that real Jammeh’s deadly serious abuses. For this reason, she said: “I believe this attempted coup did not fail.” She is now devoting her own considerable energies, however, to a more personal cause: an American military funeral. “This became his country,” Sigga said. “To have a military burial with his kids there, it would be closure.”

The Kentucky National Guard seemed amenable, but Sigga wasn’t even sure where her brother was. When we talked in April, rumour had it that Njaga’s body was sitting in a Banjul mortuary, under 24-hour military guard. But Jammeh’s government refused to either provide any information or to turn the remains over to the Jagne family. Due to the circumstances of his death, the United States seemed unwilling to press for repatriation. Since then, the body has completely disappeared, but there’s been no indication of a decent burial. As far as anyone knows, Captain Jagne rests on a cold slab, somewhere a long way from home.