PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Cotton bud in ear: Why can’t we resist the temptation despite the warnings?

Roberto A Fredman | Thursday 28 January 2016 | THE INDEPENDENT

Years ago, my mother complained about a terrible earache. The pain was unbearable, and it wouldn’t go away. For a week, she walked around with a debilitating ringing in her head. Eventually, she recalled to me the other day, the discomfort led her to a doctor, who carefully pushed an otoscope into her ear. Within seconds, he pulled it out and looked her in the face.

“Have you been putting Q-tips in your ears?” he asked with a disapproving tone.

Familiar in Britain, “Q-tips” is the name of the proprietary brand of cotton-swab, or bud, in America. And like so many others, my mother had been using them to clean her ears. But in doing so she was also messing with a natural process. Her ear was hurting because she had an ear infection, and there’s a decent chance her routinely using cotton buds had helped to cause it.

“Promise me something,” the doctor told her. “Promise me you’ll never put another Q-tip inside of your ear.”

Cotton buds are one of the most perplexing things for sale in the West. Plenty of consumer products are widely used in ways other than their core function – books for levelling tables, newspapers for keeping fires aflame, soda water for removing stains, coffee tables for resting legs – but these swabs are distinct. They are one of the only, if not the only, major consumer products whose main purpose is precisely the one that the manufacturers explicitly warn against.

The little padded sticks have long been marketed as household staples, pitched for various kinds of beauty upkeep, arts and crafts, home-cleaning, and baby care. And, for years, they have carried an explicit caution – every box of Q-tips comes with this caveat: “Do not insert inside the ear canal.” But everyone – especially those who look into people’s ears for a living – know that many, if not most, ignore the warning.

“People come in with cotton-swab-related problems all the time,” says Washington otolaryngologist Dennis Fitzgerald. “Any ear, nose and throat doctor in the world will tell you they see these all the time. People say they only use them to put make-up on, but we know what else they’re using them for. They’re putting them inside their ears.”

While Q-tips were never sold for use deep inside the ear, it took around half a century for manufacturers to explicitly warn against it. Originally, the versatile little household staple was the brainchild of a man named Leo Gerstenzang, who thought of wrapping cotton tightly around a stick after watching his wife preen their young child. She was using a toothpick with a cotton ball on the end to carefully apply various things to the baby, a clever but easily improved trick.

In 1923, Gerstenzang introduced Baby Gays, the first sanitised cotton swabs. They were similar to those sold today, save for a few key differences. They were made of wood, instead of plastic or paper; they were single- not double-ended; they were meant to be used for baby care, rather than everything under the sun; and, most importantly, they didn’t discourage putting them inside ears. “Every mother will be glad to know about Q-tips Baby Gays (the Q stands for ‘quality’), sanitary boric tipped swabs for the eyes, nostrils, ears, gums and many other uses,” a print advertisement read in 1927.

In the years that followed, many things changed, including the name, which was shortened to just Q-tips; the material, which shifted to paper; and the marketing, which broadened to include all sorts of other household uses. But one thing didn’t: the absence of a warning.

It wasn’t until sometime in the 1970s that boxes began to caution against sticking the things inside of ears. A vintage box from shortly after the new labelling practices says “for adult ear care” on the front. But the box also sports directions on the back advising against using them inside the ear canal. Today, the warnings are even more explicit. They say, rather unambiguously, “Do not insert swab into ear canal.”

What exactly prompted the change is unclear. There is no record of a publicised case around that time in which a cotton bud was blamed for damage to someone’s ears. Nor does Unilever, which now owns Q-tips, attribute the shift to anything in particular. “The brand has been around nearly 100 years so there’s been a few iterations in packaging,” says Carolyn Stanton, a company spokeswoman. “The earlier boxes were intended for baby care so it wasn’t relevant at the time.”

But the impetus for the switch must have come, at least in part, from an understanding that many people were misusing the cotton swabs. Which makes it all the more mysterious that – despite the cautionary label added to packaging – Q-tips continued, as they had been for decades, to be marketed as a tool for ear cleaning.

In 1980, a commercial for the brand featured the comedy actress Betty White, who encouraged people to use them on eyebrows, lips and ears. (“This is a Q-tips cotton swab,” she said. “They call it safe swab.”) A separate television spot, cushioned with uplifting music and cute animation, showed a child using the cotton swabs on a dog’s ear, and then a mother using them on a baby’s ear. No wonder that, in 1990, a piece published in The Washington Post joked that telling people to use the swabs on “the outer surfaces of the ear without entering the ear canal” was akin to asking smokers to dangle cigarettes from their lips without ever lighting them.

The cigarette analogy is an apt one. We continue to twist cotton buds in our ears thanks to a simple truth: it feels great. Our ears are filled with sensitive nerve endings, which send signals to various other parts of our bodies. Tickling their insides triggers all sorts of visceral pleasure. But there’s more. Using them leads to what dermatologists refer to as the itch-scratch cycle, a self-perpetuating addiction of sorts. The more you use them, the more your ears itch; and the more your ears itch, the more you use them.

Fitzgerald, the otolaryngologist, says he appreciates the cigarette analogy but insists there’s nothing funny about the temptation to stick cotton swabs into your ears. At the heart of the problem is a fundamental misunderstanding that he believes manufacturers have helped propagate, even if unintentionally, by talking in advertisements about their use in ear cleaning.

“People have been led to think that it’s normal to clean their ears – they think that ear wax is dirty, that it’s gross or unnecessary,” he said. “But that’s not true at all.”

Fitzgerald likens ear wax to tears, which help lubricate and protect our eyeballs. Wax, he says, does something similar for the ear canal, where the skin is thin and fragile and highly susceptible to infection. “Your body produces it [ear wax] to protect the ear canal,” Fitzgerald says. “What you’re taking out is supposed to be in there. There’s a natural migration that carries the wax out when left alone.”

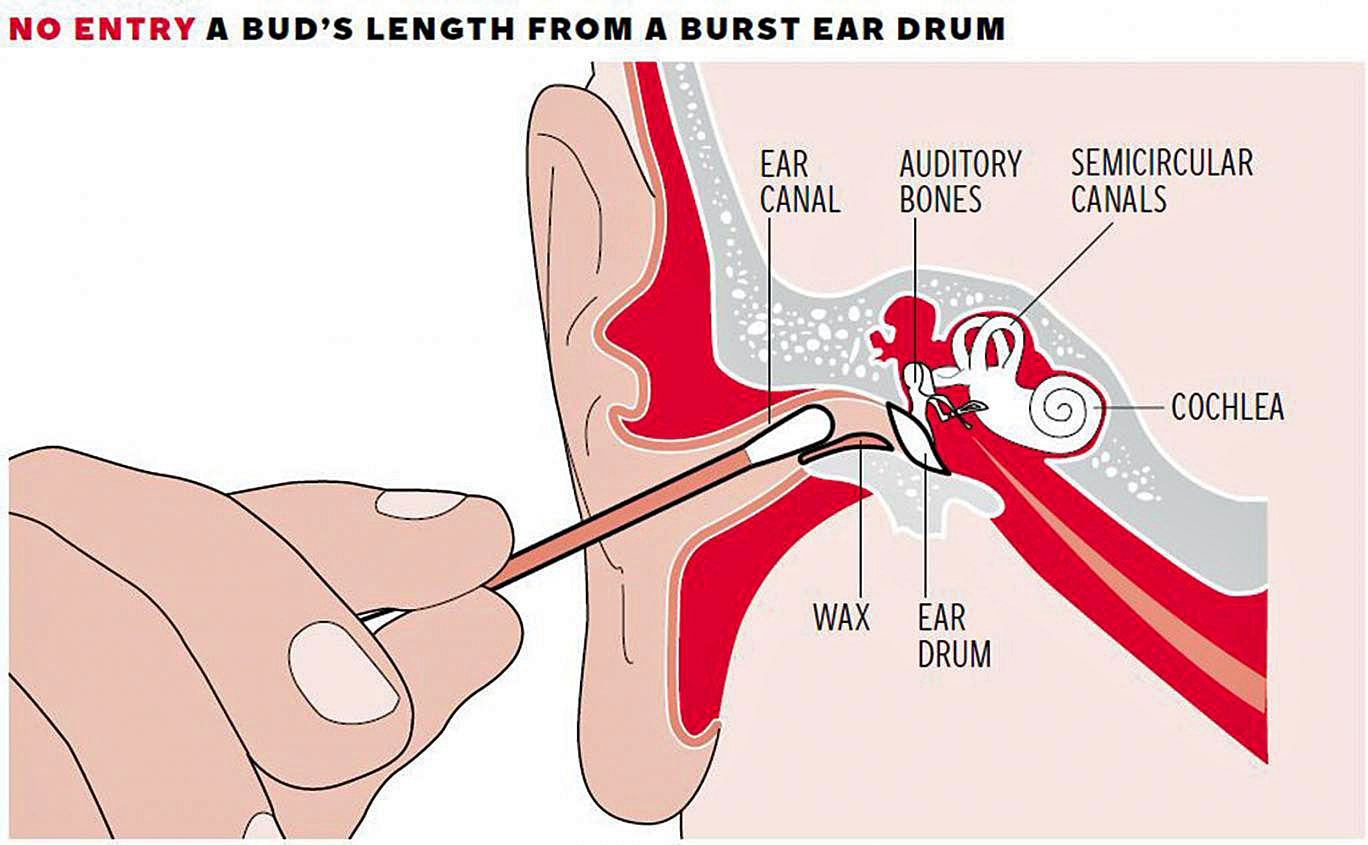

Even if our ears were meant to be cleaned, the truth is that buds would still be a terrible thing to use, he says. The shape, size, and texture are such that inserting them into your ears tends to push wax inward, toward your ear drum, rather than woo it out.

“Pushing wax in can induce hearing loss,” says Fitzgerald. “They can also be inserted too deeply and rupture the ear drum or damage the small middle ear bones, both of which happen more than you would think.” For this reason, the American Academy of Otolaryngology listed cotton swabs as an “inappropriate or harmful intervention,” even when earwax needs to be forcibly removed from the ear, in its 2008 guidelines.

It’s surprisingly hard to figure out how often people hurt themselves by putting Q-tips in their ears each year. In Britain, the Office for National Statistics can’t help. In the US, where the Consumer Product Safety Commission tracks injuries associated with all sorts of household goods – including cotton balls – it doesn’t track those associated with cotton swabs, because they are considered medical devices and are therefore overseen by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

“It would be very tedious to figure out how many injuries associated with cotton swabs were reported each year,” says Deborah Kotz, an FDA spokeswoman. But she does suggest searching the agency’s database for reports, which turn up several instances in which people have incurred injuries after using cotton swabs inside of their ears and bothered to file a report. In one case, a patient filed a complaint after cleaning their ears “for the first time as recommended by a friend”. In another, a consumer complained that the cotton had separated from the stem.

But doctors don’t need a government database to know that cotton swabs are a problem. A 2011 study by the Henry Ford Hospital found a direct association between the use of cotton swabs inside ears and ruptured ear drums. It also noted that “more than half of patients seen in otolaryngology (ear, nose and throat) clinics, regardless of their primary complaint, admit to using cotton swabs to clean their ears.”

Fitzgerald, who says he can immediately tell when someone has been using Q-tips, laments that the warnings aren’t working: “I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve told someone to never put them in their ears and then been told that they had no idea.”

Today, there is not a single ear on the official Q-tips website in the US. There’s a woman using the cotton swabs to apply make-up to her lips, another using them for nail polish, a dog, a baby and a sparkling clean living room, among other things. The variety reflects Q-tips’ business strategy, which increasingly has been driven by a desire to broaden the product’s appeal.

“The marketing expanded to ‘all purpose’ use in the late 1990s and 2000s,” says Svetlana Uduslivaia, who is the head of tissue and hygiene at Euromonitor, a market research firm. The firm estimates there were $208.4m (£146m) in Q-tips sales in the US in 2014, up from $189.3m in 2005. “People may use it for ear cleaning, but we instruct against it,” says Stanton, of Unilever.

The problem, of course, is that people do. Barbara Kahn, who teaches marketing at the Wharton School of Business, said it’s particularly difficult to change how people perceive Q-tips because they are such a historic brand. “They’re trying to change how people think of the product, to build a brand that’s separate from the original and inappropriate use, but that’s really hard when everyone knows a product and thinks about it in a certain way,” she says. “If people are telling others to use Q-tips for their ears, if that message is coming through virally through videos or some other media, or just moving from customer to customer, that’s a very powerful thing they can’t control.”

She adds: “There’s really no way to stop it short of taking the product off the market, which they’re obviously not going to do.” And Fitzgerald agrees. “If it were up to me, they wouldn’t be on the market,” he says. “When I treat people with recurring ear problems, I make them promise they’re going to throw away their Q-tips and never buy them again. The ones who keep coming back with infections are the ones who don’t listen.”