PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Freedom by the Numbers

Ilya Lozovsky | 29 January 2016 | FOREIGN POLICY

Freedom House’s index of freedom in the world is flawed — but the story it tells is indispensable.

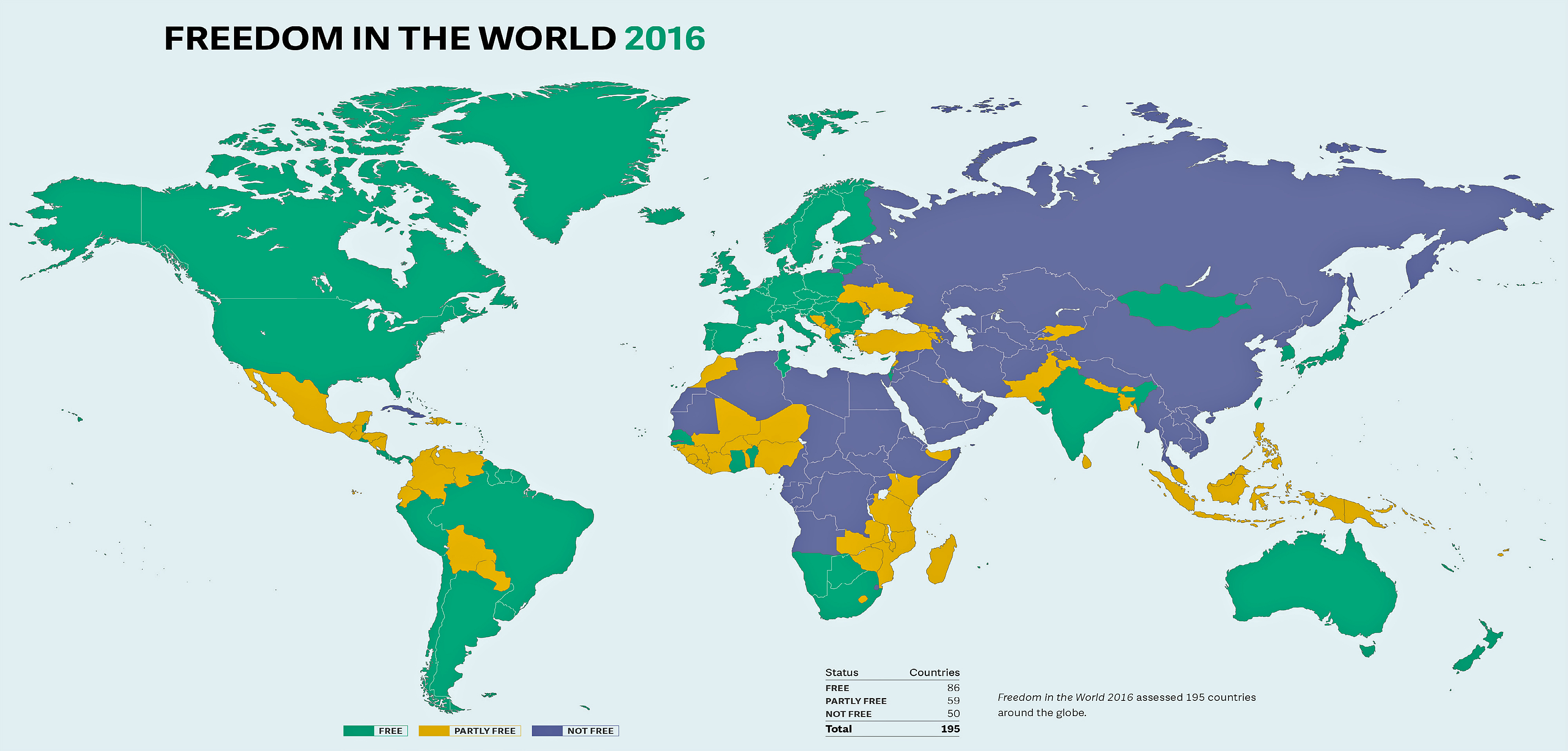

It’s January, which means we’ve just learned that freedom around the world is declining. This — for the tenth year in a row — is the conclusion of an annual report released earlier this week by Freedom House, the venerable human rights and democracy organization. Freedom lost ground in 72 countries in 2015, the report somberly concludes. This is the largest such number over this gloomy ten-year period, during which the percentage of the world’s population that lives in “free” countries declined from 46 to 40 percent.

These annual “Freedom in the World” reports, which describe and numerically rate the state of freedom in every country on earth, inevitably generate buzz, and this year will be no exception. And it’s not just the media. Ministers, diplomats, Washington policymakers, U.N. bureaucrats, and other international wheelers and dealers will be paying close attention. There’s little doubt that diplomatic cables reporting the latest scores are already flying — and in some capitals (I’m looking at you, Budapest) you can almost hear the gnashing of teeth.

In spite of all this commotion, the ivory tower regards the exercise with a mixture of skepticism and exasperation.

In spite of all this commotion, the ivory tower regards the exercise with a mixture of skepticism and exasperation. Over the last decade, political scientists have produced a wealth of literature documenting the annual reports’ biases and methodological problems. Their conceptual basis is flawed; the data collection is opaque; the results are overly simplified; Freedom House has a neo-liberal bias. Jay Ulfelder, a political scientist and independent consultant, has convincingly disputed Freedom House’s overall findings — that freedom in the world is steadily declining — for two years in a row.

And yet, flawed as they may be, Freedom House’s ratings still matter. They are a crucial tool for pro-democracy activists. They drive dictators crazy. And, perhaps most important of all, they get worldwide attention. The reason is simple: Unlike the number crunchers, Freedom House knows how to tell a story. And in the world of international human rights advocacy, one good story is worth a thousand finely tuned disaggregated indicators.

There is good reason to treat the critics’ complaints seriously. Start with the obvious: how do you assign a number representing an “amount of freedom” to every country on earth? One social scientist — who has worked on several Freedom House reports — put it quite simply:

“The numbers are bullshit.”

“The numbers are bullshit.” The problem is that each country’s scores aren’t really a measure of anything concrete — they are, in essence, assigned by feel. The people Freedom House hires for this job are generally experts on both the country in question and on democratic processes, so it’s not a question of competence. Rather, the problem is that awarding 0 to 4 points for each of a country’s 10 political rights indicators and 15 civil liberties indicators is, by definition, an arbitrary exercise.

Take just one of these indicators, which are phrased in the form of questions: “Is there open and free private discussion?” So what’s the score going to be? Two? Or three? What, exactly, does either choice mean? And are the dozens of researchers assigning scores to other countries interpreting the scale in the same way? The problem is compounded by the fact that Freedom House doesn’t release these subscores individually; only in the aggregate. As a result, “scholars laugh at how bad the measure is,” said the social scientist (who declined to be named to preserve a good relationship with Freedom House), adding that graduate students who try to use the scores in a study get a “polite but firm talking-to.”

Freedom House’s Arch Puddington, who is in charge of the reports, dismisses such criticisms, emphasizing that each country’s scores are reviewed, and adjusted as necessary, by additional experts and a core group of Freedom House staff. He has also promised more transparency: in future reports, he said, each score for each indicator will be made publically available.

But there’s a more fundamental problem that no review committee can address. No matter how carefully or systematically the scores are assigned, first you have to decide what you’re going to measure — and on this there can be no widely accepted consensus. Do you think “free trade unions and peasant organizations” and “effective collective bargaining” are as important as an “independent judiciary”? Freedom House does. But when these subjective judgments are collapsed into just a few numbers — which are then treated as authoritative, impartial measures of something called freedom (or democracy; the distinction is often blurred) — the result is something of a conceptual mess.

To try to resolve these issues, or at least address them in a different way, a host of alternative indices have been devised in recent years. The problem is that, unless you’re a democracy scholar, it’s a safe bet you haven’t heard of any of them. Perhaps the most ambitious is one of the most recent: faced with the impossible task of creating a single scientifically rigorous measure of freedom, the V-Dem index doesn’t attempt to do so at all. Instead, it divides “democracy” into seven high-level principles, each of which are subdivided into about 400 minute and highly specific indicators with precise definitions and scoring guidelines, all of which are made publically available. This makes this index much more useful to academics than the Freedom House scores, which, in any event, were always meant more for advocacy than research.

Alexander Cooley, a political scientist who has recently co-authored a book critiquing the spread of international rankings, has a broader criticism. Why, he asks, do we need to “delegate our understanding of a particular country’s democratic trajectory to Freedom House? Why is it that we let these indicators and these scores about countries be a shortcut for our own judgment for grappling with these issues?”

There’s a simple answer. It’s because people who are not democracy scholars (including diplomats and policymakers) can only pay so much attention to complex topics outside their areas of expertise.

In their most extreme act of simplification, Freedom House’s reports boil down a host of complicated phenomena into a single value for each country: “Free,” “Partly Free,” or “Not Free.”

Yes, it’s a shortcut — but people need shortcuts.

Yes, it’s a shortcut — but people need shortcuts. Journalists need them when they’re trying to understand a country on deadline. Activists need them when hammering home an important point to a bored politician. Diplomats need them when pressing a reluctant government to open the window of freedom just a crack wider. And, in our schizophrenic, distracted age, we all need them to make sense of just what in the hell is actually going on.

The most effective shortcut of all is a story — and this is where Freedom House really excels. Unlike any of the other indices, Freedom in the World comes with an overview essay that paints a portrait of what happened over the previous year. The full version of the report also includes a detailed narrative for each country, noting the most important developments and providing context for the raw numbers. The reports are illustrated with colorful charts and maps. And with the full might of a 75-year-old organization behind them, they reach audiences around the world. A document published by V-Dem itself notes that the Freedom in the World index gets almost 367,000 Google hits. The next-most popular, Polity IV, gets just a fifth of that number, and none of the others come close. It’s telling that, while producing these reports constitutes just a small fraction of Freedom House’s budget, they are, by far, the main thing the organization is known for.

This makes the index a powerful policy tool. International development agencies follow each year’s results and use them to guide their policies. The Millennium Challenge Corporation even makes achieving some minimum score a formal requirement before it will disburse assistance. United States diplomats, too, pay close attention. A 2010 diplomatic cable from the embassy in Bahrain criticizes Freedom House for being too harsh on the U.S. ally (and repressive dictatorship). A 2007 cable from Cambodia, on the other hand, describes Freedom House’s upgrade of the country’s press rating from “Not Free” to “Partly Free” as a victory in its battle to get the government to clean up its act (Freedom House’s “Freedom of the Press” report is distinct from “Freedom in the World,” but uses a similar methodology).

Foreign governments — especially those that are sensitive about their reputations — watch the reports closely.

Foreign governments — especially those that are sensitive about their reputations — watch the reports closely. Russian officials, who have long had it in for Freedom House for its essential documentation of the country’s slide into authoritarianism, reacted with particular vehemence in 2007 after media reports inaccurately described Russia as having been given the lowest possible rating. Other governments respond more constructively. Freedom House’s Arch Puddington noted that the organization has had “half a dozen meetings with diplomats and other officials from Hungary in the past 4-5 years… because [they] take seriously our scores, which call into question the democratic bona fides of the government.” When Kyrgyzstan was not upgraded in Freedom House’s press freedom report after its 2010 revolution, the new government was furious — and immediately dispatched a delegation to discuss the results.

“Freedom in the World” works not because it’s scientifically rigorous — it works because it deftly packages a complex phenomenon into a powerful, easily-understood message. In that way, it betrays its origins as a labor of love by one man: Raymond Gastil, a social scientist who worked for Freedom House for nearly two decades, developed the survey and ran it for many years until it was taken over by a larger team in 1989. And, today no less than during the Cold War, it’s stories, not statistics, that have the power to change the world.

(Disclosure: The author worked for Freedom House’s emergency assistance program from 2012-2014. He did not play any role in the composition of any of the organization’s reports.)