PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

“We have many like him,” Nega said.

Nega put on his jacket to head off in search of diesel fuel for the morning journey to the border. With another rebel comrade from Virginia, we drove down the deserted, lightless streets of Asmara, searching for an open filling station, but the one we found had run out of diesel; Nega would have to return the next morning, delaying his departure for the front lines. When we returned to his home, Nega pointed to a pile of medical supplies in the hallway — bandages, splints, antibiotics, antimalarials — that he was planning to ferry to his fighters, and three cardboard boxes packed with solar cells that would provide some rudimentary electricity in the bush. While in the camps, Nega was dependent on his mobile phone for contact with the outside world, but even that was not guaranteed. “They have shut off phone coverage since the incursion” by the Ethiopians at Tsorona, he told me. “I’ll be out of touch for days.”

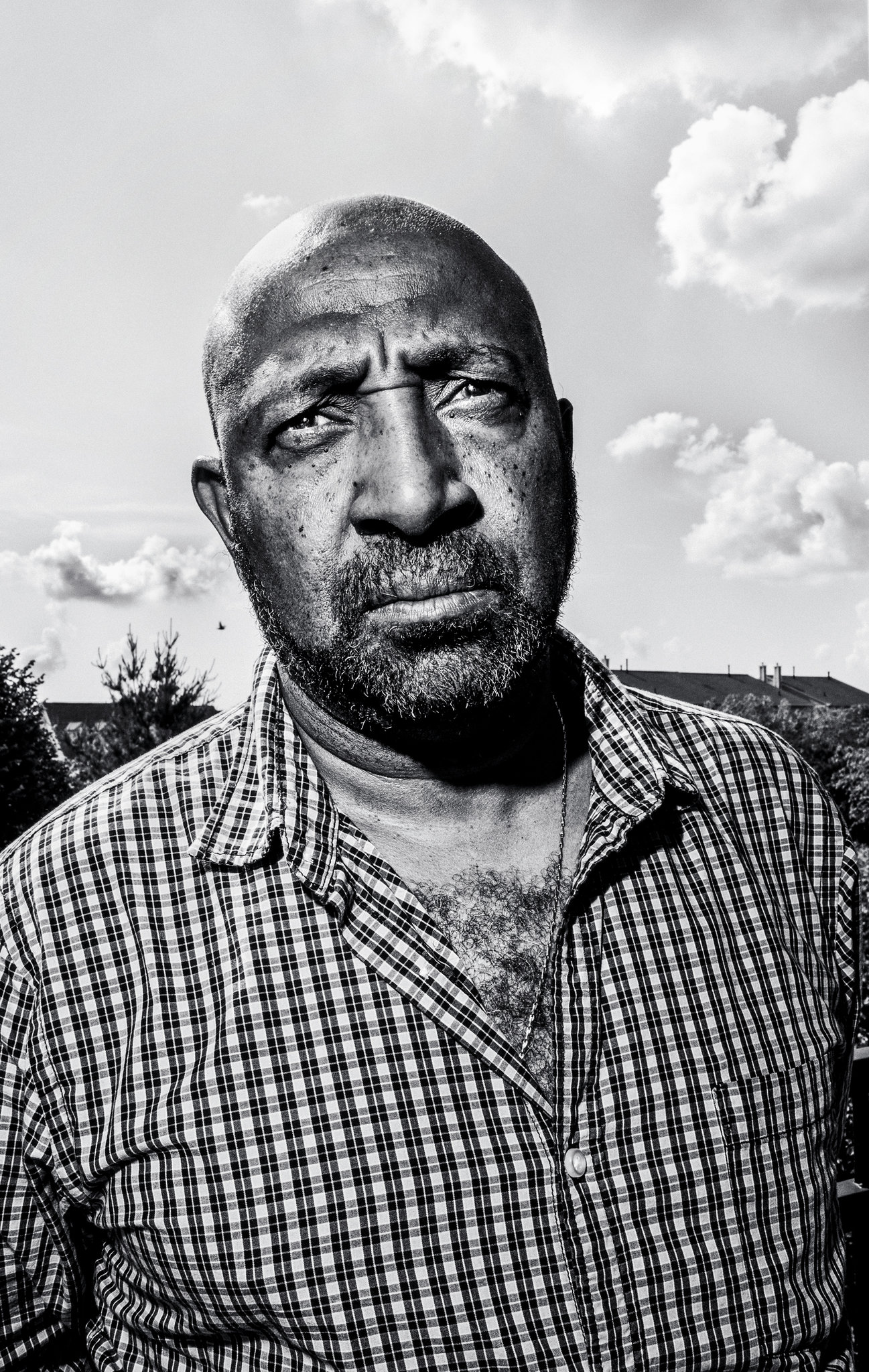

When I first met Nega, in late May 2016, the conditions were decidedly more comfortable. After 10 months in Asmara, Nega had flown back to the United States to attend meetings and the graduation of his younger son, Iyassu, from the University of Pennsylvania. Given his deepening involvement in a rebellion against an American ally, it was possible that this would be the last time he could visit the United States. Indeed, Nega, who is not an American citizen, had his State Department-issued “travel document” suspended three years ago, and his application for United States citizenship has been put on indefinite hold. He now travels on an Eritrean passport; together with his green card, it gained him entry into the country — this time. The State Department would not comment on Nega or Ginbot 7, but Nega surmises that the Obama administration does not look favorably on his activities. Still, he insists, “nobody is saying, ‘Back off.’ I think they know that this is not about being against the U.S. We are upholding the basic principles under which the U.S. was established.”

We met over Memorial Day weekend on the terrace of the upscale Café Dupont on Dupont Circle in Washington, joined by his sister Hiwot, who runs a technology start-up in New York, and Iyassu, a 21-year-old former high-school track star who was starting work at a New York investment bank in the fall. Over white wine and chicken salad, the conversation touched on Lin-Manuel Miranda’s commencement address and Nega’s excitement over crossing paths, after the ceremony, with Donald Trump and Vice President Joe Biden. (Trump’s daughter and Biden’s granddaughter were members of Iyassu’s graduating class.) I asked Iyassu if he had reconciled himself to the idea of his father’s new life on the front lines, and he said that he had. “Ultimately he should continue to pursue what he believes in,” he told me. He expressed little interest, though, in visiting his father at his Eritrean rebel camp or delving deeper into the raison d’être of the Ginbot 7 movement. “I just got out of college — my life has its own direction,” he said. “I can’t take time off. … I’m a little bit removed generationally as well.”

The elder Nega is part of a generation of Ethiopians who grew up amid violence and tumult. Over lunch, he recalled what it was like to be a high-school student when a Marxist junta, the Soviet-backed Derg, overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie and ushered in a brutal dictatorship. Nega had grown up privileged, the son of a wealthy entrepreneur, and he watched as his father’s vast commercial corn and soybean farms were seized and security forces began arresting, imprisoning and executing thousands of dissidents, including many students. He and his two older sisters joined a resistance movement called the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (E.P.R.P.). They went underground, living in safe houses, eluding the police. His eldest sister was later captured and disappeared in the Derg’s prisons. His family searched for her everywhere.

“We had people coming to our house and telling my parents, ‘I saw her at this place.’ My mother used to go out all over looking for her,” Nega recalls. Her former cellmates later told him that she had died in prison, probably by committing suicide with a cyanide capsule that she wore around her neck. “It was common to have cyanide with you because if you were caught, you would be tortured and executed, and through torture you might be forced to betray people,” Nega said. As the crackdown in Addis intensified, the E.P.R.P. sent Nega north to Tigray province, the center of a growing guerrilla war against the Derg; there, he carried out attacks on government forces. In 1978 a power struggle erupted within the E.P.R.P. leadership, and Nega was thrown into prison. He was released one day before guards turned their guns on the remaining prisoners, killing 15. Nega escaped to Sudan, living as a refugee in Khartoum for nearly two years, then obtained political asylum in the United States in 1980.

B

B