PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Mark Anderson in Asmara for The Africa Report | Wednesday 28 September 2016 | The Guardian

"We don't take sides; we help you see more sides."

Published:

PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Mark Anderson in Asmara for The Africa Report | Wednesday 28 September 2016 | The Guardian

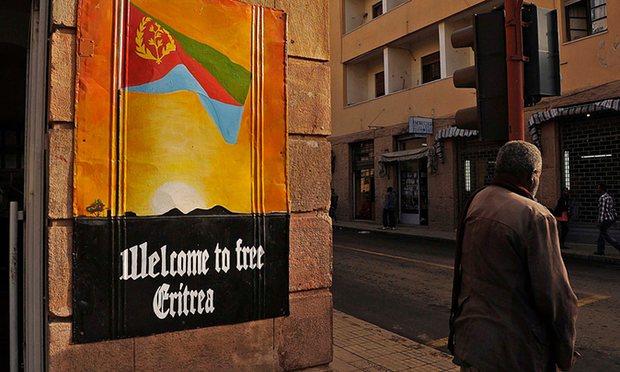

Outside a cafe on the crossroads of a busy intersection in Asmara, three 25-year-olds sip macchiatos and catch up on the latest gossip in the bright morning sunshine. The conversation soon turns to people who have “skipped”, a term for those who have fled Eritrea to escape the indefinite national service programme.

Birhane, 25, who works as a mechanic in a government-owned garage, said: “Between us, we probably know about 300 people who have skipped in the last few years. They are leaving because we have to do what the government tells us to do.”

In 1991, when Birhane, Henok and Adonay were born, Eritrea had just gained independence from Ethiopia after 30 years of war. In the early years, many people were optimistic about their future and their leaders.

Today, the atmosphere in Asmara is markedly different. Isaias Afewerki, the former leader of the liberation struggle, is still in power 25 years later, and a resumption of hostilities with Ethiopia at the turn of the millennium inflicted huge human and economic damage on the country, exacerbating its slide into a military state.

In the capital, although bicycles and charming old European cars dot the roads and the ambitious Italian colonial-era architecture is well preserved, more than a dozen people said they were desperately gathering cash to pay for sigre dob (border crossing).

Gaim Kibreab, a professor of refugee studies at London South Bank University, says Eritrea is the world’s “fastest emptying nation”. About 400,000 people are estimated to have left the country in the past decade, from a population of just 5.1 million.

The UN and human rights activists estimate that as many as 5,000 Eritreans flee illegally every month, but the Eritrean government claims that the real number is closer to 1,000, because Ethiopians often pretend to be Eritrean when seeking asylum abroad.

Those left behind in Asmara say everyone is well aware of what is happening. “I know of thousands of people who have left,” said Demsas, 49, as he strolled down one of the main streets. “We can feel it.”

The government acknowledges that people are leaving in droves, but says it is part of an international conspiracy to weaken Eritrea. “The policy of the United States for the past 10 years has been to encourage the migration of Eritreans, especially Eritrean youth and especially Eritrean educated youth,” said Yemane Gebreab, the director of political affairs for the ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) and a close advisor to Afwerki.

“If they can encourage migration and especially desertion from the Eritrean army, which has been a main objective of this policy, then they will have achieved their aim of weakening Eritrea,” he said.

For law-abiding Eritreans, it is hard to avoid the national service programme. Hundreds of soldiers are known to storm neighbourhoods in Asmara every few months. Known as a giffa (raid), troops block off traffic and set up a cordon before going house to house in search of people who have not enlisted.

Young Eritreans say they feel trapped by these policies. If they are caught deserting, the government hands down brutal punishments. But if they stay, they are resigned to a life earning a monthly wage of 500 nakfa (£25). “All of us are still in national service. We don’t get enough [money] to live on,” Henok said.

The government has recently changed some elements of national service, a sign that the regime may be aware of the damage its policies are causing. Those drafted in 2001 or earlier are being allowed to leave active service, but they are still required to work for the government. The maximum salary offered after demobilisation is 4,000 nakfa, equivalent to $165 on the black market, according to Hagos Ghebrehiwet, the PFDJ director of economic affairs.

Last year, the government put a limit on the amount of money that people could withdraw from their bank accounts, saying it wanted to encourage citizens to use cheques and mobile money facilities. Hagos said: “Cash is the basis for illegal activities, like human trafficking.”

However, very few businesses accept cheques or credit cards, and since the introduction of the rule, the black market dollar exchange rate has halved, leading to speculation that the policy is a covert way to limit the number of people fleeing.

“With this new currency, people don’t have access to their money,” Demsas said. According to human rights activist Meron Estefanos, wealthy Eritreans can pay high-ranking government officials between $5,000 and $6,000 to be smuggled out of the country and driven to Khartoum in Sudan. The fee for a similar journey across the border with Ethiopia is $2,000 to $3,000, she said.

For most Eritreans, who do not have rich friends or relatives overseas, the journey to Europe is extremely expensive. Natnael Haile, who lives in Sweden, says he was drafted into the army aged 13. After spending seven years repairing army cars on a desolate military base, he crept out of his dormitory in 2008. Haile paid smugglers $400 to take him to Sudan, where he was kidnapped and sold to nomads in the Sinai desert.

Haile ended up paying a total of $7,100 to get on a boat heading for the Italian island of Lampedusa. But the account of his harrowing journey does not deter Adonay and his friends in Asmara. “We would all leave tomorrow if we had the money,” they say.