PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Following the Money: On the Trail of African Migrant Smugglers

Alexander Bühler, Susanne Koelbl, Sandro Mattioli and Walter Mayr | September 26, 2016 | Spiegel International

Since 2013, over 10,000 migrants have drowned while attempting to cross the Mediterranean to Europe. Behind the deaths lies a multi-million dollar smuggling trade with financial connections to Frankfurt, Italy and Libya.

He is the most wanted migrant smuggler in the world but there are no photos of him, only an artist’s rendering that investigators produced. It depicts a heavyset man with short hair. He is thought to be an Ethiopian in his early 40s and is suspected of having been in the business for the last 10 years.

On the phone, his voice sounds dark and guttural and he chooses his words carefully, his Arabic occasionally punctuated by English words. Words such as “life jackets,” which he used in an intercepted telephone call after one of his ships sank off the coast of Lampedusa on Oct. 3, 2013. “I have never sent along life jackets, is that clear?”

On that day, 366 people drowned as they sought to make it to Europe, within sight of the island of Lampedusa, when their vessel went down. The man who organized the voyage of the wooden boat was vexed by the disaster — not so much because of the deaths, but because it wasn’t good for his reputation. “So many refugees have set off with other organizations and become fish food,” he said. “But nobody talks about them.” Only he is being hunted, he complained.

His name is Ermias Ghermay.

The rules of this murderous business are dictated by Ethiopians, Sudanese and Libyans, but particularly by men from Eritrea. Their homeland is one of the poorest countries in the world, a single-party dictatorship referred to by Human Rights Watch as a “gigantic prison.” More than a million Eritreans have fled abroad, representing a huge market for Eritrean migrant smugglers, who are increasingly using the central route across the Mediterranean.

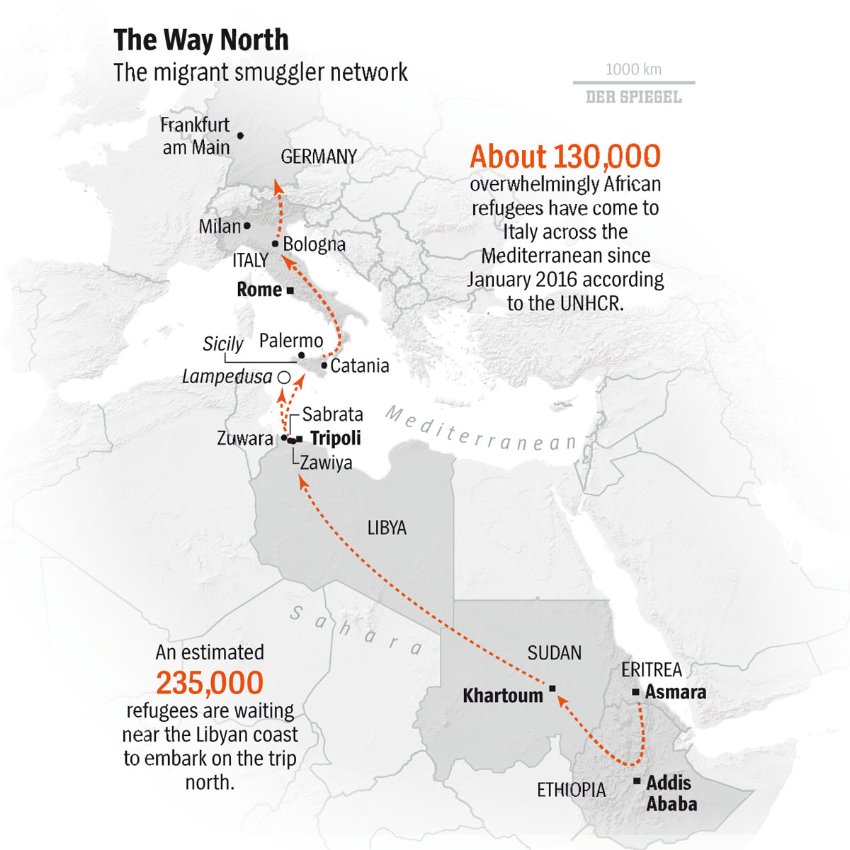

As logs of phone calls intercepted by Italian prosecutors show, the smugglers’ envoys in Khartoum, Tripoli, Palermo, Rome, Frankfurt and elsewhere are extremely well networked. Spread across the route, they guide their compatriots northward — and rake in millions in the process.

DER SPIEGEL spent months reporting on the migrant smugglers’ network, spending time in Libya, Italy, Frankfurt and Berlin. We examined more than one thousand pages of case files, evaluated confidential records and spoke with refugees who survived the trip across the Mediterranean. The reporting painted a clearer image of the cynical migrant smugglers who are willing to accept the deaths of thousands, who lock up refugees and sell them like livestock.

One of the most notorious of these smugglers is Ermias Ghermay.

TRIPOLI, LIBYA

The police station belonging to the crack unit known as Tarik al-Sika is located on the eponymously named street in the heart of the Libyan metropolis. This is where the adversaries of Ermias Ghermay and other smugglers are headquartered. For foreigners, the complex had always been off limits, until now.

A steel gate opens onto a courtyard. To the left are the offices belonging to investigators and special forces. To the right are the prison cells. Tarik al-Sika is an elite unit responsible for hunting down human traffickers and members of extremist militias. In contrast to the chaos that has become normal in Libya, the situation here is well-regulated: The shift schedule hangs on the wall and records of the unit’s operations are carefully filed away in folders.

Hussam, the shift supervisor, who requests that his last name not be used for security reasons, is wearing a T-shirt and jeans rather than a uniform. He wears his facial hair in the style popular among members of the militia group Libya Dawn: a carefully sculpted half-circle from ear to ear, passing below the lower lip. He wears his hair in a ponytail.

“We know where he and his men are, who they work with, where their movements take them and where they live,” he says when asked if he has an idea where Ghermay might be found. He grabs a file and recites what they know: Until 2015, he says, Ghermay lived in a part of Tripoli populated mostly by African migrants, an area notorious as a transfer point for drugs, weapons and alcohol. Hussam says that his unit raided Ghermay’s apartment twice, but he managed to escape both times. Currently, he continues, Ghermay is hiding out with his heavily armed bodyguards in Sabrata, a coastal town in western Libya. Unfortunately, he adds, Libyan security officials don’t have enough people or weapons to go after him there.

There are many migrant smugglers who brag openly about their excellent relations with the Libyan police and claim that they can even get anyone out of prison simply by buying off law enforcement officers. When asked about such claims, Hussam says that the phenomenon doubtlessly exists in Libya, but not within his unit.

“Ermias is an Ethiopian with Eritrean citizenship and dresses inconspicuously in jeans and a T-shirt,” says Yonas, a former intermediary for Ghermay who stands almost two meters (6′ 7″) tall. Ever since Tarik al-Sika arrested him at his workplace — in the cafeteria of the Eritrean Embassy in Tripoli — several months ago, Yonas, whose name was changed for this story, has been cooperating with Libyan special forces. On the day of our visit, he was presented as an important witness. Yonas says that he used to earn 50 dinars, around 30 euros ($33), for every Eritrean refugee he referred to Ghermay — and that some of them were aboard the vessel that sank off the coast of Lampedusa. On the night of the accident, Yonas says, “Ermias slid a passenger list under the door of the Eritrean Embassy so that their families could be informed” — a cold-blooded move that Ghermay is proud of, according to the logs of intercepted phone calls. The relatives of the victims, most of whom came from Eritrea, were thus promptly “informed,” he gloated. It’s the kind of gesture that is good for business.

“Immediately afterwards, I called him and set up a meeting in the cafeteria. I wanted to get him to pay compensation to the families,” Yonas says. “He actually turned up, but in the end, he only returned the price for the voyage. Nobody got any more than that.”

The refugees have only themselves to blame for their deaths, Ghermay said in a telephone call to a migrant smuggler from Sudan, adding that they didn’t follow his instructions and carelessly caused the boat to capsize. He insisted that he had a clear conscience. “If I followed the rules and they died anyway, then it’s fate,” Ghermay said.

The man from Sudan agreed: “There is no appeal against God’s judgment.”

SABRATA, LIBYA

The ruins of the old Sabrata theater can be seen from quite a distance. Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site, it stands witness to a more glorious past under the Roman philosopher king Marcus Aurelius. Today, the several-thousand-year-old city is a hub of international crime and a transfer site for the huge sums earned from human trafficking.

Most of the migrants travelling from Sub-Saharan Africa these days end up in Sabrata and it is also the launch point for many of the boats heading for Italy. Most of the refugees have already travelled thousands of kilometers by the time they reach the city — and spent thousands of dollars. Eritreans who have already managed to make it across Ethiopia to eastern Sudan have to pay up to $6,000 ( 5,400 euros) for the continuation of their journey to the Libyan Mediterranean coast via the Sudanese capital of Khartoum. For most of them, it is a journey full of suffering, with many taken hostage in the Sahara — locked up and systematically abused — until their families back home send money for the next stage of the trip.

Eighteen-year-old Fanos Okba, who was raped in one such camp before surviving the tragedy off the coast of Lampedusa, says: “We were forced to stand the entire day and watch as other migrants were tortured in a variety of ways — with electric shocks, lashes to the soles of their feet and with a rope that was tied around their legs and neck in such a way that even the smallest movement could lead to their strangulation.”

To end their suffering, family members have to pay, sending money to accounts in Sudan, Israel or Dubai. Or they sent the ransom money using the Middle Eastern transfer system known as “hawala.” It is a system that works on the basis of trust: one person accepts the money on consignment and a second person pays that exact same money out to the end recipient elsewhere in the world. Only when the sum demanded has been received does the family of the captured refugee receive a code that they must then send to the mobile phone of the migrant smuggler. Only then can the trip northwards continue.

A Tight Ship

Once they reach the Libyan coast, Ghermay’s clients are again locked up, usually in warehouses in Sabrata or on the outskirts of Tripoli. The refugees are given registration numbers to make recordkeeping easier: not unlike in the wholesale livestock trade. Ghermay maintains “direct contacts with migrant smugglers in Sub-Saharan Africa,” it says in Italian case files. That allows him to “buy loads” of migrants from other smugglers “to increase his own profits.”

Ghermay’s senior henchmen, who demand to be called “colonel,” run a tight ship. It costs money to keep refugees in the warehouses, which is why those who cannot immediately pay for the passage to Italy are tortured, beaten and worse. According to the aid organization Save the Children, there have been cases of children being held for months and forced to drink their own urine so as to avoid dying of thirst.

All of this is taking place in a country that was granted an “immediate and substantial” aid package worth 100 million euros from the European Union in April 2016. It is happening as ships from Germany and elsewhere in Europe — part of an EU mission called Sophia — are patrolling so close to the Libyan coast that migrant smugglers only have to spend a pittance on boats and fuel. A rickety tub, a few liters of diesel and a satellite phone for the emergency call are all that’s necessary.

The Libyan King of Migrant Smuggling

According to Libyan investigators, Ermias Ghermay is currently living in a neighborhood located just behind the Sabrata water tower. “He roams from city to city,” says Major Basem Bashir, the head of the police unit charged with investigating illegal migration in the coastal town. “He is extremely dangerous. Our sources say that he is currently living here.”

Recently, Sabrata officials warned that the city’s morgue was unable to accept any more bodies of deceased foreigners, saying the building was simply too small to hold all of African migrants that wash up on its beaches: people from Sudan, Nigeria and Eritrea. In July, there were more than 120 bodies, 53 of them showing up on a single day, according to the mayor.

Ghermay isn’t the only migrant-smuggling magnate who lives in Sabrata, Major Bashir confirms. The entrepreneur Dr. Mosaab Abu Grein is here as well. Investigators in Tripoli believe he is the Libyan king of migrant smuggling. According to people in town, Mosaab Abu Grein is a 33-year-old father of two sons who has a respectable demeanor and, officially at least, a spotless reputation. There is no international warrant for his arrest. According to officials, he is the owner of the largest beach club in Sabrata but has declined to respond to the accusations made by investigators.

Hussam, from the anti-terror unit in Tripoli, merely shakes his head when asked if European investigators are familiar with the findings of their Libyan counterparts. “You Europeans are constantly complaining about the masses of refugees from Africa,” he says. “But none of your investigators or prosecutors from Italy or Germany has come to Tripoli to ask what’s going on here.”

PALERMO, ITALY

He has a wide face, black eyes and wears a necklace of plastic pearls: According to the Italian warrant for his arrest, Atta Wehabrebi maintained “direct relationships with the smugglers in Libya, including Ermias Ghermay”:

According to Calogero Ferrara, Atta is a “key witness.” The tanned, angular public prosecutor with a cigarillo in the corner of his mouth is clearly proud. Here, in Ferrara’s Palermo office, Atta spoke for the first time, in April 2015. The Eritrean’s testimony, says Ferrara, is as valuable as admissions by leading Sicilian Mafiosi once were.

Ferrara works for the legendary anti-mafia brigade of the Palermo public prosecutor’s office. Each morning, on his way to his office on the second floor of the palace of justice, he passes a plaque commemorating several of his murdered predecessors. Judges Paolo Borsellino and Giovanni Falcone, both murdered in 1992, also worked in this building. “There are lots of things that don’t work in Italy, but we know something about fighting organized crime,” Ferrara says.

According to the Sicilian investigators, the smugglers’ enormous crimes justify measures just as drastic as those taken against the Cosa Nostra. The Italian judiciary allows investigators to tap phones and perform video surveillance. Key witnesses are treated generously, including witness-protection programs.

So far, the Palermo prosecutors have conducted three large operations to shut down the cells of Ghermay’s smuggling network — “Glauco 1” to “Glauco 3.” Seventy-one warrants have been issued. During the last big raid in June, two thirds of the 38 accused were from Eritrea. There have also been convictions — including that of Atta, who now lives in a witness protection program. “Everything we know about this network is thanks to him,” says Ferrara.

Atta came to Libya from Eritrea at the age of 13, and later lived on the same, middle-class Tripoli street as Ermias Ghermay. During the Gadhafi era, he ran a café there where would-be migrants would stop before attempting to cross the Mediterranean. Atta collected their money for the trip and sent it along to the smugglers.

In 2007, he fled to Italy and from there he took advantage of his contacts to the big players in the smuggling business. He rose up the hierarchy, becoming, according to the arrest warrant, one of the “bosses and co-founders” of the criminal organization, along with Ghermay and a Sudanese man named John Mahray. He was responsible for operations on Italian territory.

Hard to Track

Atta was in charge of transporting the refugees who arrived in Sicily further north. He had to get them out as soon as possible — before the Italian authorities could take their fingerprints. Without fingerprints, the refugees are hard to track. Without them, officials in Germany can hardly tell who comes from where.

Atta drove some of the migrants personally, without a driver’s license, in cars to Germany and even to Scandinavia, an easy game in a Europe without border controls. In other cases, he sent accomplices; they left Bologna for the Bavarian city of Rosenheim at around 9:30 p.m. He motivated his helpers by telling them: “You’ll be back at 6 a.m. and you’ll have earned 1,000 euros.” He advised his helpers: “If you are caught by the Germans, tell them you don’t know the people in the car, and you’ll be out of prison one day later.”

According to Atta, the sale of registration notices, marriage certificates and personal status certificates was especially lucrative. Some of his Eritrean accomplices, he claimed, had simultaneously filed applications in five different Italian prefectures with five different registration notices for family reunification with five different “wives” who were supposedly still in Eritrea.

The women, who then received the necessary entry papers, were thus spared the dangerous boat trip across the sea. For that reason, they also paid up to $15,000 for their fake marriage. And the whole thing, Atta says, works so well because the Italian prefectures don’t compare information with one another.

The Italians can afford this kind of nonchalance. Although in the past year alone, 38,000 Eritreans reached Italy illegally, the overall number of Eritreans in the country has gone down by 30 percent since 2011 — to the current number of 9,600. Every year, tens of thousands go north after their arrival — onward to Switzerland, Sweden and Germany. These include the very poor, but also wealthy smugglers.

The German authorities know about it, Ferrara claims, thanks to the European justice authority Eurojust — but he says they apparently don’t care. “We Italians are conducting investigations, issuing warrants, encouraging Eurojust coordination meetings. We have documents which suggest that the network has contacts to Germany.” According to Ferrara, 40,000 wiretap transcripts have been sent to colleagues in other EU countries via Europol. Ferrara sought their help in determining how well connected the murderous smuggling syndicate now is.

‘I’m Sick of It’

The UK, Sweden and the Netherlands, Ferrara says, evaluated the data and started to conduct their own investigations: “The Germans, however, have done nothing. They don’t seem especially interested either. At one Eurojust meeting, they had an intern take part. But I’ve also heard the same sentence from the German side for the hundredth time: ‘We are prepared to help the Italians’ — and to be honest, I’m sick of it.”

Are the Germans arrogant or naïve? Ferrara suspects the latter: “It reminds me a bit of my mafia investigations. There, too, the Germans had a tendency to say, ‘Mafia? Doesn’t exist here.’ Germans close their eyes to the truth — even though we have given them sufficient evidence.”

German investigators claim that the Italians informed them too late. They say that the Italians shared their evidence only after the “Glauco 1” and “Glauco 2” operations had already been concluded. In security circles, one hears that the work is made even more difficult by the structural differences between the two systems in Germany and Italy.

A friendly man with an office not far from the Palermo cathedral is particularly critical of the Germans. Carmine Mosca leads a special anti-migrant-smuggling division within Squadra Mobile, the police’s mobile task force.

Mosca was there in June in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum during the extradition proceedings of a migrant smuggler for whom an international arrest warrant had been issued. He lauds the cooperation with the British National Crime Agency, which helped capture the smuggler, and with the Dutch, who, he says, always have an ear open for Italian concerns. But when the conversation turns to the Germans, he struggles to control his anger.

It’s actually not so complicated to capture people like Ermias Ghermay, says Mosca, but the task is repeatedly made unnecessarily more difficult for him and his team. Normally, for example, an EU rescue ship from the Sophia mission docks in a Sicilian harbor with hundreds of refugees on board. “We drive there to investigate,” says Mosca. “We ask who the smugglers are and about phone contacts to Libya, that we can later monitor. Most of the crews — the Irish, the Spaniards, the Norwegians — are very well organized and welcoming.”

But, he claims, there is one exception: the Germans. One time, he relates, the frigate Hessen docked with maritime refugees on board. “Officers didn’t even let us on board the ship. They didn’t support us in any way, gave us no evidence. No briefing, nothing. We were unable to arrest a single smuggler afterwards.”

And this despite the fact that, as Mosca claims, he had three Italian prosecutors with him at the time. Even they were turned away by the Germans. The whole thing, the investigator says, is hard to fathom: “We are here in Italy, they are bringing us migrants and they don’t even let us on board to find out how the rescue went.” Among the crews of all of the EU ships, he says, the Germans stick out with their “truly singular behavior.” He says there is no useful contact: “The German liaison officer in Italy? Never heard, never seen.”

‘I’ll Have Them Sleep Standing Up’

When asked by DER SPIEGEL, the commander of the Hessen said he “cannot recall” incidents when Italian authorities were denied access to the ship. The Defense Ministry added that in mid-2015 a “mandate for the fight against smuggling-crime in the Mediterranean” had yet to be issued. During joint operations, access to ships is certainly provided “as needed.”

On Sicily, an historical intersection point between Europe, Africa and the Middle East, it has become impossible to overlook the consequences of the thousands of shipwrecked arrivals. It’s enough to follow the tracks Atta, the key witness, has provided to the investigators. In Palermo, for example, in the Vicolo Santa Rosalia alley. There, in an unremarkable bar, is where the smugglers housed their human cargo until a raid in July. Today, you can see young men looking out at the street with a mirthless look in their eyes, their cheeks filled with leaves of khat, a popular drug on the Horn of Africa.

And those searching for the house in Catania where Ghermay’s brother once housed 117 refugees — “if necessary, I’ll have them sleep standing up,” he said in one recorded phone call — will find, just a few steps away, the makeshift outdoor hovels belonging to the stranded.

About 400 kilometers linear distance away, in Rome, the Eritreans have their base in the Palazzo Selam, a glass palace that once housed Tor Vergata University’s Institute for Philosophy and Humanities and now gives shelter to up to 2,000 refugees. Two of the migrant smugglers who had warrants issued for their arrest in June were registered here while a few others were registered by the Jesuits in central Rome.

There, inside Via degli Astalli 14a, Pope Francis’ followers run more than just a soup kitchen; they also offer specific services behind their green iron door. Refugees without a permanent place of residence are allowed to use their postal address if they want to make an application for asylum or a visa. And, for that reason, seven of the 28 warrants issued during “Glauco 3” were delivered to the Roman Jesuits.

But that’s not all. Atta, who lived in a bourgeois brick building with a view of the Alban hills in Rome during his time as a smuggler, gave many more clues in his 10-hour interrogation. Parts of his testimony are still classified, under the highest level of secrecy. “We are now working on operation ‘Glauco 4’,” says prosecutor Ferrara: “This time it’s about the financial streams; we have asked for the support of several intelligence services. Because you need to follow the money.”

FRANKFURT, GERMANY

To understand where the millions earned by the migrant smugglers end up, one should embark on a search for Ermias Ghermay’s wife, Mana Ibrahim. She has applied for asylum in Germany, says key witness Atta. “She is now living in the Frankfurt area. All the money that Ermia earns is in Germany.”

Officials in Palermo claim to have forwarded all the data they have about Ghermay’s wife to their German counterparts. But in Germany, nobody knows anything about Mana Ibrahim: Nobody at the agencies responsible and none of the investigators. Yet they claim that they carefully pursue all leads.

In response to a request for comment submitted by DER SPIEGEL, Frankfurt prosecutors said that Frankfurt is without a doubt one of “the German focal points of Eritrean smugglers,” and that “around 10 to 15 proceedings” pertaining to their activities were recently carried out here. The division for organized crime, they said, has repeatedly launched investigations targeting the “commercial smuggling of foreigners.” Mostly, though, they have only managed to capture bit players.

Meanwhile, Palermo investigators complain that several major migrant smugglers from Ghermay’s organization — for whom arrest warrants have been issued — are still at large in Germany. In previous years, significant figures in the smuggling industry were only tracked down in Germany in response to entreaties from Italy. Measho Tesfamariam, for example. He stands accused of being responsible for one journey across the Mediterranean that resulted in 244 migrants disappearing without a trace in June 2014. Afterward, the Eritrean traveled to Germany and applied for asylum. In December 2014, investigators found him in Müncheberg, a town in the eastern German state of Brandenburg.

Financial Aid for a Dictator

In Italy, numerous criminal complaints, such as rape, bodily harm and domestic disturbance, had been filed against Gurum, who denied all accusations against him. He applied for asylum in Germany using his real name. When an extradition request for Gurum landed on the desk of senior prosecutor Mario Mannweiler in the nearby city of Koblenz, he initially thought it was merely another routine case of legal cooperation, as he now recalls. Yet the grounds for the extradition request stated: “Membership in a criminal organization.” The requested cooperation was swiftly provided and Gurum was handed over to the Italians in short order, but German prosecutors, Mannweiler says, are chronically overburdened. “It’s not easy to find someone who is interested, who wants to dig deeper.”

So is Germany simply blind to the perpetrators who come into the country via Libya and Italy? Or are the country’s laws to blame? In Italy, just being a member of the Mafia is a crime, but not in Germany. Here, there has to be evidence of a crime committed before an arrest can be made.

The European Union is hoping that the refugee crisis can be solved with money. The goal of the so-called Khartoum Process is to provide financial aid to countries on the Horn of Africa and other states along the migrant routes. Among the recipients of such aid is the brutal Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir, who is set to receive millions from the EU. One EU action plan aims to strengthen the Eritrean government’s institutions and personnel — a government that Amnesty International has accused for years of “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment” of those who would dare to question it.

But it won’t be possible to stop the Eritrean exodus with an injection of money. Already, Frankfurt is home to Eritrean Orthodox and Ethiopian Orthodox congregations, an Eritrean consulate and, behind the central train station, bars and restaurants where Eritreans gather. One of them told us how he once met Ermias Ghermay in Khartoum with the help of a friend from the migrant smuggling scene. “Like many major migrant smugglers, he retreats to Sudan in the fall and is part of the top circles there,” the young man says. He says that the attempt to get African officials to combat the smugglers is in most cases absurd. “In Sudan, generals in uniform greet Ermias Ghermay like a close acquaintance. He stands under their protection and when he returns to Libya, he is protected by the Libyans.”

ZAWIYA, LIBYA

The rows of small mounds of sand in the cemetery not far from the town of Zawiya seem almost endless. White blocks, hundreds of them, maybe a thousand, serve as grave markers for the nameless bodies that have washed up on the beach. Here and there, where the sea breeze has blown away the sand, a jacket can be seen poking out, or a bone. The tattered pages of a book about the Old Testament flutter in the wind. Perhaps they once belonged to a Christian Eritrean who is now buried here.

A few kilometers further on, a half-dozen men from the Coast Guard in Zawiya are gazing out to sea. Their spokesman, who they refer to as Colonel Naji, is clearly making an effort in his new role spearheading the fight against human trafficking. Since Aug. 30, teams like his have been receiving training from the EU and now, when they see a refugee boat, they are supposed to bring it back to shore.

Colonel Naji says he thinks it’s a good thing that Germany is supporting his men in the fight against human smuggling. But he still has a piece of advice for his allies to the north: “You have to change your asylum laws. The smugglers are now using you like a taxi service that picks up their customers safely and for free just off the coast of Libya.”