PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Jason Burke in Addis Ababa |

"We don't take sides; we help you see more sides."

Published:

PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

By AHN

Jason Burke in Addis Ababa |

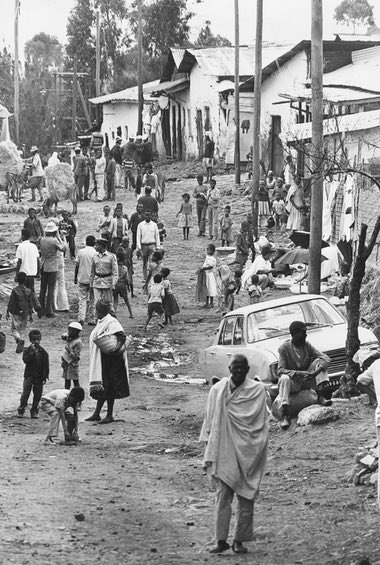

Drive out of Addis Ababa’s new central business district, with its five-star hotels, banks and gleaming office blocks. Head south, along the traffic-choked avenues lined with new apartment blocks, cafes, cheap hotels and, in the neighbourhood where the European Union has its offices, several excellent restaurants. Go past a vast new church, the cement skeletons of several dozen unfinished housing developments, under a new highway and swing left round the vast construction site from which the new terminal for the Ethiopian capital’s main international airport is rising.

Here, the tarmac gives way to cobbles and grit and the city loosens its hold. Goats crop a parched field beside corrugated iron and breezeblock sheds, home to a shifting population of labourers and their families. Children in spotless uniforms neatly avoid fetid open drains as they walk home from school. Long-horned cattle wander. Beyond the airport, the road splits into a series of gravel tracks that quickly become dusty paths across fields, which take you to the village of Weregenu.

There is nothing remotely exceptional about Weregenu. It is just another cluster of flimsy homes like many others around, and within, Addis Ababa. Nor is there much exceptional about the series of demolitions here over recent months. As the Ethiopian capital expands, it needs housing, rubbish dumps, space for factories. All land is theoretically owned by the government, merely leased by tenants, and when the government says go, you have to go. So Weregenu’s thousand or so inhabitants know they are living on borrowed time. All have been warned that the bulldozers will come back.

“The police came with officials a few weeks ago. We had a day’s warning,” says Haile, a 19-year-old former resident. “Old people, children, pregnant women … It didn’t matter who you were or where you came from, your house was smashed to bits.”

“No one told us why they wanted the land, except it is needed for development. We’ve been living there for years and years. I grew up there. Now we have to find somewhere else, or pay rent – and we can’t afford it.”

All over the developing world, there are people with similar stories. By 2050, according to the UN, over half of Africa’s population will live in cities, a much lower proportion than elsewhere in the world but twice as high as now. Ethiopia is one of the countries where urbanisation is moving fastest, and like elsewhere the process is placing massive strain on established political, economic and social systems. One result, as elsewhere, is violence.

The unrest in Ethiopia started in late 2015 with a small demonstration at a town where locals suspected officials of planning to build on a popular football pitch and a forest reserve. They rapidly intensified, prompting a brutal reaction from security forces. This prompted more protests and, inevitably, more brutality. By early autumn last year, several hundred people were dead and the unrest had become a full-blown political crisis.

Accounts of the violence are harrowing. Security forces have shot into crowds of unarmed schoolchildren, students and farmers. Footage of such incidents shows teenagers bleeding on the ground just metres from officials. Police have gone from house to house hunting suspected protesters, combed universities for activists who are then beaten with rifle butts or worse, and picked up any politicians suspected of dissent. Many detainees simply disappear. There is evidence of extra-judicial executions, while prisoners describe being kept for weeks in solitary confinement in dark cells, subjected to successive interrogations and beatings.

“I had no idea if it was day or night,” one prisoner, a musician held for weeks in prison in Addis Ababa last year, remembers. “I was interrogated for about two weeks, and punched or slapped. Then they tied my wrists together and hung me up by my arms from a hook. They hit my hands with sticks, breaking the bones. I passed out.”

When he regained consciousness, the 31-year-old was treated for his injuries and then held for a further two months in a “big hall, deep underground” where more than 100 detainees lived on water and bread, using a bucket for a toilet. He later fled overseas, where he spoke to the Guardian.

Many of the protesters were young, so a high proportion of those killed or injured were teenagers. Security forces targeted those who provided assistance or shelter to suspected activists, too. Parents, friends and schoolmates were detained to pressure fugitive children to turn themselves in. Two teenage athletes who defected while in South Africa for a competition last summer described how friends and relatives had subsequently been roughed up and detained. “They have been rounding them up,” one said.

The protests continued throughout last year at a rate of more than one a day. Some factories were burned, a few vehicles torched and occasional stones thrown. The government described the protesters as “armed gangs”. The numbers of dead or injured demonstrators mounted.

The final act came in October at Bishoftu, a city 35km from Addis Ababa, during a vast religious festival. When some among the crowd of hundreds of thousands began to raise slogans against the government, security forces moved in, firing tear gas and, some witnesses claim, live ammunition. In the stampede that followed, at least 100 died, according to western officials who watch Ethiopia. Activists claim the number was many times higher. The news prompted a new wave of protests. A state of emergency was declared, followed by mass arrests.

Ethiopia had long been held up as one of Africa’s star economic performers and an island of stability in an anarchic region. Though recent months have been calmer, the fallout from the unrest of the last two years may still dramatically change the history of one of the continent’s most important countries – and possibly the future of hundreds of millions of people across the entire continent. The questions posed by the crisis here are vital ones. Does the accelerating expansion of cities – from Algiers to Dar es Salaam, from Cairo to Kinshasa – inevitably mean violence? Will urban development heal existing tensions between communities in fragile nations or aggravate them? Could it be economic success, rather than failure, that brings revolution?

Gataa, an activist, is slim, small, bespectacled and in his mid-40s. He is inconspicuous, sitting and sipping water in northern Addis Ababa while he talks softly of protest, death, detention and violence.

Gataa (not his real name) is an Oromo, the largest single ethnic group within Ethiopia, comprising 35-40% of the population. The Oromo have played the principal role in the recent unrest, suffered the most significant casualties and been arrested in the greatest number.

The primary grievance outlined by Gataa is that the Oromo have been oppressed for centuries by other ethnic groups in Ethiopia, first the Amhara, which comprise somewhere between 25-30% of the population, and, more recently, the Tigrayans, only 6%. Many Oromo, and others, say the current government is dominated by the Tigrayans, at least behind the scenes, who are also viewed as benefiting disproportionately from recent economic growth. Both charges are contested by officials and nuanced at least by many analysts and historians. But there is no doubt that there is a powerful Oromo identity and a strong sense of grievance.

“We are marginalised in everything,” says Gataa. “All the best jobs, the contracts, the power is with the others. It has always been this way.”

In 2014, municipal authorities in the capital had published a new strategic document outlining the future development of the city. In most places, this would be a mundane exercise attracting little attention. But for Gataa, and millions of others, “the Addis Ababa integrated zone master plan” was far from innocuous. Ethiopia is split into nine regions, each one for a different ethnicity, and two cities that run themselves. Addis Ababa is one of these, and is effectively an enclave within Oromia, the state of the Oromos. The state resembles a belt of territory straddling the country with Addis as the buckle. The “integrated zone” covered in the plan included a 1.1m hectare strip of land around the city, outside the current municipal boundaries. A glance at a map shows how the expansion of the Addis Ababa it described would have neatly bisected Oromia.

“It is a land grab, an eviction, a new invasion,” says Gataa. “This is Oromo land. Already we have been pushed to the outskirts of the city. Now they push us further so they can build and develop and construct. The farmers have to go. They get jobs on the construction sites on the land where they lived. There is no question of compensation, or any benefit. So what do you expect? Land is everything for the Oromo. It is our culture and identity. It is a matter of life and death.”

If discontent and resentment at the government cuts across all ethnic groups, the Oromo had a powerful narrative to frame their grievances – and to mobilise.

“This was a rallying cry,” says Gataa. Half a dozen activists in the influential Oromo diaspora – from the US to South Africa – echoed his words.

The masterplan of 2014 did not prompt immediate protests however. Officials say this is evidence that unrest was manufactured from overseas, a charge Oromo activists inside and outside Ethiopia deny. Either way, the protests rapidly left the original issue of the masterplan far behind, almost everyone interviewed for this article said. Many recent demonstrations have been in the Amhara region, where there are few Oromo, but similar frustrations.

“The masterplan was a trigger but not the cause,” says Gataa. “It seems calm now but under the surface much is happening. We are gathering our forces now. People are talking, meeting, organising. Now no one – not even the young people – is interested in [economic] growth. Once you have lost faith in the government, everything is dark for you.

“Am I afraid? Yes, but when those in the front line fall, others will take their place.”

That Addis Ababa is in dire need of planning is not in doubt. It was founded in 1886, by the emperor Menelik II, who is widely seen as the architect of modern Ethiopia and whose statue now towers over a busy roundabout in the capital’s scruffy, lively neighbourhood of Arada. In the 1930s, just before Italy’s short-lived occupation of Ethiopia, the British writer Evelyn Waugh described the city as being “in a rudimentary state of construction” with “half-finished buildings at every corner”. Just over 30 years later, the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinsk told his readers of “the wooden scaffoldings scattered” about a city that resembled “a large village of a few hundred thousand, situated on hills amid eucalyptus groves”. The hills are still there, as is the wooden scaffolding, which is more practical in the heat and sun than its steel counterpart. The trees are gone.

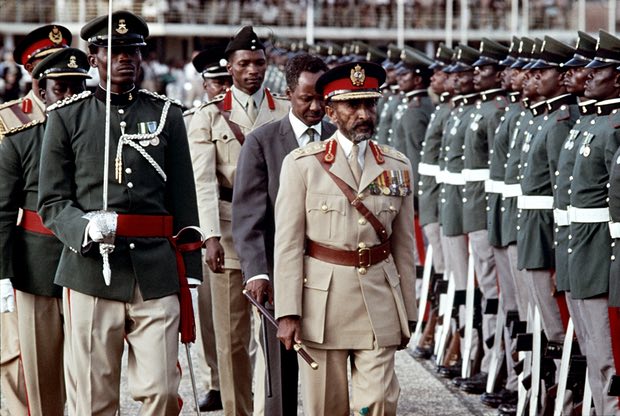

The growth of Addis Ababa has been extraordinary. In 1974, when Haile Selassie was deposed in a military coup after 58 years as emperor and regent, its population was estimated to be half a million at most. By 1991, when the brutal “Derg” regime was finally ousted by rebel groups, there may have been double that number, living at around 2,300m in a dusty bowl below the Entoto hills. Today there are somewhere between 3.4 and five million people living in Addis Ababa. Most are without proper sanitation or clean water, many lack steady electricity, there is limited public transport and rubbish collection is grossly inadequate. The World Bank expects the city’s population to double over the next 10 to 15 years.

“This certainly raises some major challenges, as it would for any city,” says a UN official who has worked on urban issues in the city. Some forecast a population of 35 million by the end of the century. So one would imagine that any effort to put in place a strategic plan to manage that expansion would have been welcomed.

Aster lost her house in the demolitions of Werengenu village. She is now living, along with her HIV positive mother and her teenage daughter, on the floor of a neighbour’s two-roomed home.

“What do you think we feel? I had a legal lease to this land,” she says, standing in the rubble of her home. “I built my house here long ago. I have friends, neighbours, relatives here. It’s a community. Where do I go know? These officials, they do not care about ordinary people. The government just work for themselves.”

When anyone is prepared to talk, and has checked over their shoulder to see who is listening, this a common charge in Addis Ababa, and partially explains the violence prompted by the 2014 planning document.

Meles Zenawi, who ruled Ethiopia from 1991 until his death in 2012, frequently said he did not believe democracy and development were linked. He pursued a political and economic model that was closer that of China the west. Along with Paul Kagame’s Rwanda, Ethiopia is often cited as the example of how a repressive and centralised government can solve economic challenges in Africa as well as, if not better than, more open but messier democratic systems. Critics argue that such development, if real, is unsustainable in the long run.

Ethiopian officials deny the accusation of authoritarianism. They point out that President Obama described Ethiopia’s government as “democratically elected” on a state visit in 2015, and that the country holds regular elections. Both are true. However Obama qualified his praise and the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) has won every major poll for more than 20 years and currently occupies every seat in the 537-strong parliament. Diplomats in Addis Ababa describe “a climate of fear” and point out that “almost all opposition politicians are in prison or abroad”. Ethiopia is ranked 140th out of 180 countries by press freedom campaigners. Bloggers are a particular target, with many held under anti-terrorism laws.

But the authoritarian development model depends on a sufficient number of citizens accepting reduced freedoms in return for a slice of the growing wealth that an efficient, competent and impartial administration delivers. A minority can be repressed, but you can’t fool everyone all the time. And increasingly in Ethiopia, despite the massive growth over recent decades, the government is seen as inefficient, corrupt and unresponsive.

The combination would be a devastating one for governments anywhere. In Ethiopia, it threatens the fundamentals on which the state has been based for decades.

“People will pay a bribe, reluctantly, if that’s what it takes to get services,” says one analyst in Addis Ababa. “They don’t like it but they will do it. But when they have to pay a bribe and still get treated badly, then that’s when they get angry.”

Then there is the inequality. According to the World Bank, the GDP of Ethiopia is $62bn, almost eight times more than in 2001. Tens of millions have been lifted out of poverty, primary school enrolment is approaching 100%, and if there are still millions who depend on aid to eat and an annual threat of hunger in many rural areas, it is almost impossible to envisage the appalling famines of 30 years ago recurring.

But the new wealth generated over recent decades is not being evenly distributed. In 2014 Ethiopia topped a list of African countries creating the most millionaires. “Sales are good, especially of imported champagne,” says the manager of a fine wine shop in an upscale neighbourhood in the south of Addis Ababa. Next door, a dozen luxury cars fill a dealer’s yard. The best-selling vehicle is the Toyota Prado, a vast SUV which costs $200,000. The owner says he sells between five and seven each week. At the same time, poverty levels, even in the capital, remain between 25-30%.

“Once there was nothing here – and people argued then,” says one leading businessman over a $10 sandwich in the Sheraton hotel. “So imagine what it is like now there is a great big pie, and everyone wants a slice.”

Three further elements are fuelling discontent across Ethiopia, the businessman said: the very large number of graduates in the country, a consequence of the vast expansion of the education system since 1991; social media, which has raised expectations among young people in the country to “stratospheric levels”; and ethnicity.

Officials know the problems that face the EPRDF as it completes 25 years in power. The Addis Ababa integrated development plan has been withdrawn, with any new planning based on the city remaining within its current administrative limits. There are frequent official statements expressing concern about corruption. The media – which is largely owned or controlled by the state – is full of stories reporting the huge social programmes, the aid effectively spent, the effort to build a million new homes in Addis Ababa, the billion-dollar coffee crop, and the vast new dams. Some criticism is also tolerated, though only where it poses no threat to the ruling party – in English-language academic journals published by thinktanks closely linked to the ruling party, for example, or English-language news websites with small readership.

At the same time, anyone or anything that is considered a threat is targeted by the full force of the state.

“Ethiopia is facing political, social and economic challenges. The new generation want to be informed and are not patient,” admits Negeri Lencho, the newly appointed minister of communications.

Lencho described last year’s state of emergency as justified and temporary, pointing out that Turkey and France have introduced similar measures in the last 18 months.

“When the government faces a group of people who are killing and destroying property, when there is no law and order, then that government has to do something,” he says. “But it is not a big deal. It is gradually coming to a usual situation.”

As for the crackdown on the media, this too is not the fault of the government. The problem, according to Lencho, is that Ethiopian journalists are not “professional” and that is partly why so many of them end up in jail.

“Ethiopia has its own system of government based on a system where media and journalists should give priority to the needs of the people,” the minister says. “The role of Ethiopian journalists comes from the real and actual needs of the Ethiopian people today. Those in prison have not respected fundamental journalistic ethics.”.

Such views are anathema to activists such as Gataa. Like many others, he calls for international intervention, or at least more vocal criticism of Ethiopia from other governments. So too do human rights campaigners overseas.

Yet, as analysts agree, this is unlikely as long as the US sees Ethiopia as a key regional ally. Diplomats in Addis Ababa talk of how advancing human rights will help stability in security in east Africa but the truth is that countering the increasing influence of China in Ethiopia, and fears over rising Islamic militancy in the region, make any significant pressure unlikely. The EU now see Ethiopia as a key actor in the struggle to slow migrant flows across the Mediterranean. There is little appetite in the chancelleries of Europe or Washington to risk chaos in a country of nearly 100 million in such a sensitive part of the world for the sake of a few thousand incarcerated activists and commentators.

“We want to heal Ethiopian democracy and make it vibrant,” Lencho says. Few major powers are likely to challenge the statement in the near future.

Analysts in Addis Ababa agree only on two things: they do not want to be quoted by name for fear of attracting the attention of the security services, and that it is very difficult to predict what happens next in Ethiopia.

Some believe the government has won. They say that the promise of reforms, a cabinet reshuffle, the withdrawal of the masterplan, a degree of “protest fatigue”, the repression and the ongoing economic growth together mean that no further unrest can be expected until the next elections, scheduled for 2020 at the earliest. Analysts point out that the political leadership retains the loyalty of the powerful intelligence services, army and federal police and even if there are many malcontents, there are also millions of people, ranging from petty officials and police officers to major business owners, who see their future welfare as dependent on the continued rule of the EPRDF. They point out that recent festival of Epiphany, which some thought might be a flashpoint for further protests in this predominantly Christian and devout country, went off without a problem and say that Ethiopia is not as fragile as some believe.

If these analysts are right, Ethiopia’s course over the coming years will encourage supporters of an authoritarian model of development across Africa and beyond.

Others, however, take an opposite view. They say the unrest has challenged the basic premises that underpin the legitimacy of the government in the country. If Ethiopians can no longer look forward to a steady evolution towards political pluralism and ethnic inclusion, coupled with a degree of material improvement, then the fundamental contract between the government and the population will break down. In this case, if there is no significant reform and particularly if there is no outlet for resentment through protest, an open media, unions or opposition parties, then the centre cannot hold for very long. As they doubt whether there exists leadership and intellectual capacity to execute the necessary changes, massive and disruptive change is inevitable. This view will encourage those who believe democracy is a prerequisite of sustainable development – though all but the most dogmatic will be concerned over the trauma such change implies.

The most likely scenario, as so often is the case, is that some kind of middle way will be found. All over Africa there is tension and friction, sometimes violence, along fracture lines that have little to do with formal frontiers between states. The “Africa rising” narrative does not fit this messy reality – but nor does its pessimistic opposite. Addis Ababa, like Ethiopia as a whole, has always charted its own path, confounding predictions and confusing pundits. This is unlikely to change now. There will doubtlessly be further waves of unrest, and detentions, repression and deaths. There will be some minor concessions from the authorities. Economic growth may slow. But it does not feel like the revolution is just around the corner.

On a Sunday, the priests’ chanting sounds out across Addis Ababa at 6am over crackling loudspeakers and the faithful file into the churches. Children join less edifying activities: street football, for the most part. By mid-morning the tourists, who never really went away despite the travel warnings (now mostly lifted), are queuing inside the national museum for a glance at the remains of Lucy, one of the earliest hominids, and middle-class families are taking selfies in its garden. Work crews in straw sun hats sweep the steps of the obelisk in Yekatit 12 square, which commemorates those who died resisting Italy’s occupation from 1936-1941.

Through the afternoon, on Churchill Street, boys sell mangoes, cheap watches, cigarettes and gums to a continuous rush of old men in crumpled suits, young women in tight dresses and older women in traditional white shawls. The packed minibuses that serve as taxis jostle and manoeuvre, watched by bored police officers.

As dusk turns to night, the fashionable lounge venues in the developed downtown neighbourhood of Bole fill with “re-pats”, who have returned from London, New York or Dubai, and there’s not a free table in the bars and restaurants of Arada, where men cluster around grilled meat and couples share bottles of beer, shouting to be heard over the music. By early evening, these bars’ multi-coloured strings of bulbs are the only ones shining in the gathering gloom. By midnight the music stops, the lights are turned off, and the remaining revellers make their way home.