PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

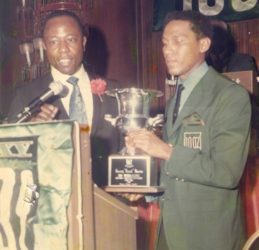

Life in Black and White (Life in BaW): The Forgotten Legacy of Bill Lucas

ALEX PUTTERMAN | JUN 4, 2017 | THE ATLANTIC

The Atlanta Braves executive became the first black man to run a Major League Baseball team—but few have followed in his footsteps in the last 40 years.

On September 19, 1976, the Atlanta Braves owner Ted Turner promoted a man named Bill Lucas to vice president of player personnel. Though Turner, somewhat oddly, kept the official title of general manager, Lucas assumed the job’s responsibilities, overseeing the Braves’ roster. As a former minor-league player who had climbed through Atlanta’s front office, Lucas was a typical hire, except for one fact: Unlike every other man to ever run a Major League Baseball franchise until that point, he was black.

Nearly three decades after Jackie Robinson had become the first black player in the modern Major Leagues and two years after Frank Robinson had become the first black on-field manager, Lucas had shattered another barrier. Sadly, Lucas’s tenure as the Braves’ top baseball executive didn’t last long: He died at age 43 of a sudden brain hemorrhage in 1979, after only two and a half years on the job. The Braves, moribund when Lucas took over, wound up winning the National League West in 1982 with a roster Lucas helped build.

Forty years have passed since Lucas’s first season as Braves’ GM, and in February the team celebrated the anniversary in a ceremony at the brand-new SunTrust Park. There, the Braves announced several plans to commemorate Lucas, including a new apprenticeship in his name aimed at diversifying the front office. But despite the recent plaudits, Lucas remains a mostly forgotten figure in the sport’s history, with little name recognition outside Atlanta—even in hardcore baseball circles.

It’s fair to wonder how much Lucas’s relative anonymity owes to the dearth of black executives invited to follow in his footsteps. Since his death, there have been hundreds of black Major League players and several dozen black managers but only five black GMs. Today, there are no black general managers (though two black men, the Chicago White Sox’s Kenny Williams and the Miami Marlins’ Michael Hill, have been promoted from GM to higher positions). In April, the Institute of Diversity and Ethics in Sport handed MLB teams a C on its annual report card for racial hiring practices when it comes to general managers.

Lucas, according to those who knew him, was a bright baseball mind and a willing pioneer. By all accounts, he did everything he could to open the door for fellow black executives. But four decades after Lucas became the highest-ranking black official in baseball, the sport faces many of the same problems it did before he came along.

* * *

At first, Lucas rejected his status as MLB’s first black general manager, his widow Rubye tells me. His race wasn’t what mattered, he figured. He was a hard worker with a quick mind and an encyclopedic knowledge of baseball, and that’s how he wished to be known. But once his first Spring Training as GM rolled around, his attitude began to change. A lifelong Jackie Robinson fan, Lucas soon realized he, too, had made history. “It really, really, really, really became important to us that perhaps his purpose in life was to show that African Americans could be in high positions in sports, and especially baseball,” Rubye, now 80, remembers.

Lucas was born on January 25, 1936 in Jacksonville, Florida, and grew up in a housing project with working-class parents. His family emphasized education throughout his childhood, and he attended Florida A&M University, where he starred as an infielder and met Rubye. After college, Lucas signed with the Milwaukee Braves but soon put his career on hold to serve two years as an Army officer. He returned for four more seasons in the Braves’ farm system, topping out at the Triple-A level before retiring in 1964. Paul Snyder, who played with Lucas in the minor leagues and later worked under him in the Braves front office, remembers him as one of the few players on the team bus who read books “that had no pictures.”

When Lucas quit playing, the Braves, who were preparing to move from Milwaukee to Atlanta, hired him as a public-relations liaison to the black community. Lucas quickly impressed the team brass in that role and soon jumped to player development, working his way up to farm-system director in 1972.

Dusty Baker, who came through the Braves’ system in the late 1960s, remembers how nervous he was to play in the South and how Lucas’s mentorship eased his worries. Baker says Lucas modeled how to get by as a black person while “maintaining your honor and dignity as a man.” “He would tell you the truth, but he couldn’t tell you everything, and you had to be smart enough to read between the lines,” recalls Baker, who now holds the MLB record for wins by a black manager.