PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Can Cyril Ramaphosa Revive the South African Dream?

William Finnegan | January 5, 2018 | The New Yorker

Not for the first time, the President of South Africa, Jacob Zuma, seems to be on the brink of toppling from office. That would be a good thing, were it to happen soon. Under Zuma, South Africa has been on a decade-long descent into kleptocratic mismanagement. “State capture” is an arcane term in most places; in South Africa, it is the standard description of the government’s relationship to certain tycoons and gangsters. The depredations of the country’s rulers are relatively well-documented, thanks to a stout free press, an independent judiciary, and a spirited political opposition. And yet the rainbow nation, once the great hope of Africa, has clearly lost its way. Inequality today is worse than it was at the end of apartheid; economic growth has failed to keep pace with population growth; unemployment and crime are sky-high. Reversing this decline is not possible during a protracted leadership crisis.

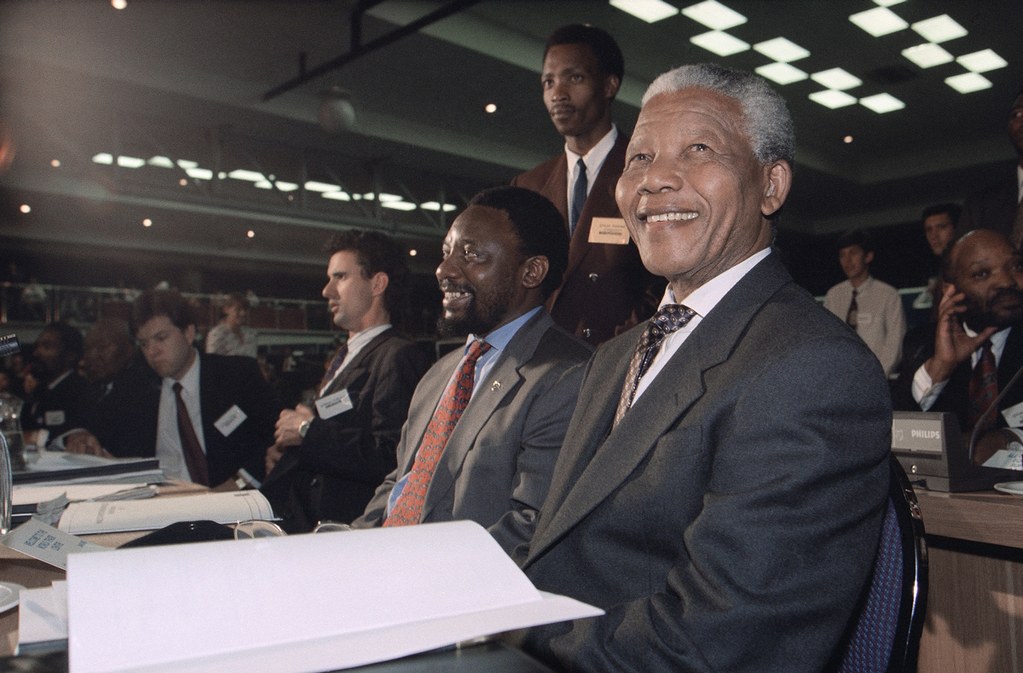

Nelson Mandela was a hard act to follow. He and his comrades achieved the seemingly impossible, turning the apartheid state into a nonracial democracy without a civil war. Mandela won the country’s first democratic election, in 1994, served one term as President, and retired—one of the very few revolutionary leaders who, like George Washington, also served as a successful head of state, and then left office gracefully. The problem of succession, however, gnawed at Mandela. His movement, the African National Congress, had two main wings in its leadership—those who had worked from exile during the decades when the A.N.C. was illegal (and when Mandela and others were imprisoned), and those who had fought apartheid from within the country. The latter group tended to be younger and more conversant with South African political reality.

Mandela’s first choice for a successor was not a former exile but Cyril Ramaphosa, an activist lawyer who remained in South Africa, founded and led the first national miners union, and then served as a lead negotiator with the outgoing white government in the talks that ended apartheid. The claims of the exiles were too strong, however, and Thabo Mbeki, an A.N.C. leader who had spent nearly thirty years overseas, became Mandela’s deputy and, in 1999, won the country’s second democratic election. Mbeki might have made a good foreign minister, but, as President, he was aloof and thin-skinned. Disastrously, Mbeki rejected the link between H.I.V. and AIDS as the epidemic of the disease struck South Africa, and he banned antiretroviral drugs from public hospitals. His beliefs seemed to arise from a combination of racial paranoia and sexual shame. Mbeki’s policies are estimated to have been responsible for some three hundred and thirty thousand avoidable deaths.

Mbeki, at least, was not notably corrupt. Zuma, another former exile—he was an A.N.C. security chief during the liberation struggle—defeated Mbeki in party elections and compelled him to resign, in 2008. The A.N.C., after more than a decade in power, had changed. Zuma was an unbridled populist, from a humble background, with no formal schooling, and a Zulu traditionalist with four wives. He had built patronage networks inside the party, not always an aboveboard process—indeed, Zuma currently faces nearly eight hundred outstanding corruption charges from before he became President, in 2009. The serious plunder began, however, once he took office: crooked public contracts, outright looting, and uncoöperative cops and cabinet ministers sacked. Zuma’s politics are heavy going. He sometimes declares that the A.N.C. will rule South Africa “until Jesus comes back.” He has suggested that his political opponents are witches. On trial for rape, in 2006, he blamed his accuser for wearing a short skirt. (He was acquitted.) His retrograde views help explain why South Africa’s three most important cities are each now administered by the opposition, the Democratic Alliance.

This political pattern may sound familiar to Americans. The populist in the White House also sees himself as the victim in a witch hunt, is reviled in the cities, often seems a buffoon, and revels in retrograde views. Yet in this country there is nothing comparable to the A.N.C., which, after nearly a century of fighting for equal rights, entered electoral politics in South Africa with enormous credibility among the country’s African majority. Under Zuma, however, the party has squandered much of that credibility with its failure to deliver greater equality and its corruption at every level. Its strategists are rightly worried about the next general election, which will be held next year. Zuma and his cronies are hugely unpopular.

Enter, once again, Cyril Ramaphosa. After he was passed over for the Presidency, the former labor leader was “deployed to business” by Mandela. Part of the grand bargain to end apartheid included a program of “black economic empowerment,” which promoted new black-owned businesses and integrated the all-white boards of corporations, including the mining companies that Ramaphosa already knew from the other side of the negotiating table. Ramaphosa joined a lengthy list of corporate boards, opened an investment firm that flourished, and got rich. His street cred took a hit, but he has not been tainted by financial scandal, and he eventually returned to politics and the A.N.C. When Zuma, who must retire in 2019, recently chose to back his ex-wife Nkhosana Dlamini-Zuma for the A.N.C. presidency—to be, that is, his successor as the country’s President—Ramaphosa stepped forward and ran against her. The Zuma camp labelled him the candidate of “white monopoly capital.” The Economist called their showdown, which culminated in voting at a party congress in mid-December, “the most visible battle in the world between good and bad government.” Ramaphosa won a close election. He immediately vowed to crack down on corruption.

Corruption is hardly the only problem facing South Africa. More than seven million people are living with H.I.V./AIDS, and ten per cent of the population still owns ninety per cent of the national wealth. The A.N.C. came to power promising “land restitution” to black communities dispossessed under colonialism and apartheid, but whites still own most of the land. Hoping to reassure investors, post-apartheid governments have quietly backed away from vows to nationalize banks and mines, and yet international credit-rating agencies have downgraded South Africa’s debt rating to junk, damaging prospects for growth. The chances that a Zuma government can stop the bleeding are effectively zero.

That’s one big reason that the anti-Zuma forces in the A.N.C. are now hoping to force him to resign, more or less immediately, to be replaced by Ramaphosa. There is also the political damage that he can continue to do by remaining in office—even hurting the A.N.C.’s chances of winning next year’s election. Last week, the country’s highest court ordered the parliament to resume an investigation of Zuma’s use of public money to renovate his country estate. The party may simply withdraw its support of him rather than face another year of ridicule and popular anger. But Zuma has already survived eight no-confidence votes in parliament. He will not go gently.

Can Ramaphosa turn all this around? Now sixty-five, he has certainly played the long game. He grew up poor under apartheid—his father was a police sergeant—and was repeatedly jailed for his activism. Over the decades, his intelligence and his integrity have impressed not only Mandela and other comrades but also his adversaries. And yet Zuma’s cronies will be thick around him now, determined to continue feeding at the public trough. This political conflict resembles the split being played out today in many countries, between unscrupulous populists and liberal democrats. But it’s also different. Africa needs South Africa, which has the strongest, most modern infrastructure on the continent, to succeed—not to become another Zimbabwe. Also, the magnificent, terrible story of defeating apartheid should not end with the defeat of the rule of law.

William Finnegan has been a contributor to The New Yorker since 1984 and a staff writer since 1987. He is the author of “Barbarian Days”.