PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

INSIDE THE AFRICAN LAND RUSH

David Ralph:

Rattling as if it might come away from the dirt-spattered ceiling at any moment to decapitate us all, a fan hacked at the heavy air in the lobby of the Econo Lodge in Dar es Salaam. ‘No soliciting’  said a sign on the wall beside the reception desk. ‘Immoral turpitude is forbidden’ said another.

said a sign on the wall beside the reception desk. ‘Immoral turpitude is forbidden’ said another.

I had checked-in the previous night, and now a dozen or so of my fellow guests sat round an ancient television mounted high on the wall opposite reception, watching intently. At the bottom right-hand corner of the screen a logo read ‘Emmanuel TV’, and a man in a silver suit holding a Bible in his left hand strode round an arena packed full of the sick and infirm. The camera zoomed in on a severely obese woman seated in a chair. She held a cardboard sign over her head: ‘I have not walked in 20 years’. The man in the silver suit placed his right hand on the woman’s forehead. She tossed and struggled for a moment until she collapsed off her chair, then rose slowly, taking a first tentative step. Stumbling across the floor like a newborn colt, tears streaming down her face, the woman waved her arms up and down, giving thanks for the miracle. The man in the silver suit held aloft his bible, bathed in the adulation, and repeated the phrase ‘Praise be’ before walking towards a skinny young boy holding a sign reading, ‘I have AIDS’.

Heading out in search of a drink in a setting more salubrious than that of the Econo Lodge, I found myself outside the tall and sleek Kilimanjaro Hotel. The path leading to the main door was covered in a thick red carpet, flanked by Tanzanian national flags alternating with Union Jacks. Once I had crossed the threshold, my shoes echoed noisily against the marble floor.

In the lobby I noticed a sign, with two arrows pointing in opposing directions. Down a corridor to the left, a state dinner was underway, according to the sign, and I now recalled that Prince Charles was in town—hence the flags up the path—to celebrate Tanzania’s upcoming fiftieth anniversary of independence from British rule. To the right, the sign said, I would find ‘Grow Africa: Agricultural Investment Forum’.

I paused, stared quizzically at the sign, and then headed right.

Outside a large marquee that had been erected to the side of the main hotel building, a young woman sat by a registration desk, talking on a mobile phone. I walked past her into the marquee and took the nearest empty seat. I opened a bottle of complimentary mineral water on the table, finishing it in two or three swigs. There were some two hundred people inside the marquee, laminated name tags swinging from their necks. Fine muslin cloths covered the tables, and low-humming air conditioners mounted at regular intervals across the ceiling set the rucked purple drapery adorning the marquee walls aflutter.

A bespectacled man standing on a stage was coming to the end of a presentation. “I think it is very unfair, much of the press coverage we have received over this,” he said in a wounded tone. The closing slide indicated that he was here on behalf of the Ethiopian government. “Thank you for listening. And please feel free to come and talk to me at the end of the session if you have any questions.”

I joined in on the hearty round of applause.

A tall middle-aged man with a grey-speckled crew-cut relieved the Ethiopian of the microphone, and, in an Australian accent, noted that that was to be the day’s last presentation. Were there any questions from the audience?

A woman in an elegantly cut white suit, who introduced herself as representing Diageo, said, “What worries us is that host governments are still not doing enough for investors.” The statement sent a low murmur of assent and heads nodding throughout the audience. A man representing Unilever said he shared Diageo’s anxiety, adding that the ‘road map’ plotted out at the meeting still lacked sufficient guarantees that investors would get a decent return.

A notepad embossed with the forum’s logo—a luscious bushel of wheat, the legend ‘Grow Africa’—lay on the table, and I began taking notes excitedly. I had stumbled, entirely by accident, into a meeting that appeared to relate directly to my purpose for being in Tanzania: to report for the Irish Times on some of the consequences of the large-scale purchase and leasing of African agricultural land by foreign investors, corporations and sovereign-wealth funds. And here in this swish marquee—I could scarcely believe my luck—were some of the biggest players involved in recent land transactions, openly discussing their plans, hopes and fears regarding African agriculture and the role they might play in its future.

I wondered how I might credibly introduce myself to the woman from Diageo. I rehearsed some questions about where Guinness sources its barley, about the land it grows on. A few tables over, I noticed a man staring hard at me. Did I look completely out of place here? I was decently dressed in slacks and a shirt, but I hadn’t shaved in days, and I did not have a name tag. Gatecrashing what looked like an invitation-only forum for high-ranking state officials and multinationals’ emissaries now began to feel like a poor decision. I shifted in my chair.

The Australian seemed to be wrapping things up. “I’m a private-sector guy, and I am detecting a lot of hesitation here in the room,” he said. “There’s a lot of energy, a lot of ideas, a lot of motivation. But I feel there’s also a lot of fence-sitting.” The Australian thanked everyone again for their contributions, and apologized for the noise of the air-conditioners. “You’ve all been very patient,” he said, at which people begun to rise from their chairs.

“Excuse me,” I heard a man’s voice at my back say. I stood up, manufactured a smile. It was the man I’d clocked staring at me.

‘Where are you from?’ he asked.

“Ireland. Yourself?”

‘I mean, who are you with?’ he said. I couldn’t locate the accent. He was in his mid-thirties at most. “Do you have an invite?”

“Oh. I was just wandering round the hotel actually,” I said. He looked me up and down, glancing at the notepad I held in my hand. “I am business student,” I lied, pointlessly, and then I said two things that were true: “I saw the sign. The forum sounds really interesting.”

His eyes ran over me again. I pictured the guards at the entrance, bored, delighted to be called on to do something. “This is a high-level meeting,” he said. “I mean, there’s a lot of high-profile people here.”

“God, I’m very sorry. I didn’t realize,” I said, still smiling, trying to read his name tag. I folded the notepad in half, slid it into my trouser pocket. “Are you staying in the hotel here?”

“No,” he said, looking me squarely in the eye. “‘I’m going to have to ask you to leave.”

“Oh. Right. God, I didn’t realize you needed an invitation.”

“It’s a very high-profile event,” he said. I couldn’t decide whether his accent was British or Dutch. “I mean, everything is transparent, but there are some pretty high-profile people here.”

Apologizing again, I exited the marquee, made my way up to the bar on the top floor of the Kilimanjaro, and ordered that drink.

Although observers disagree about the extent, the nature and the implications of what is widely known as ‘land-grabbing’, there is no disputing that the acquisition of agricultural land in poor countries in Africa and elsewhere by rich-world actors is happening on a dramatic scale. It has been the subject of major reports by the World Bank, which identifies both opportunities and dangers in the phenomenon, and by Oxfam, which describes it as a ‘scandal’ and says, “The new wave of land deals is not the new investment in agriculture that millions had been waiting for.”

Why has African land suddenly become so attractive an investment option? In a continent that has gone from being a net food exporter in the 1960s to a net importer today, why this newfound international interest in the agricultural sector?

Part of the answer lies in the food-price crisis of 2007-8, during which world food prices increased to an extent not seen for forty years. The causes of the spike are still widely debated, but it is generally agreed that rising oil prices, along with dwindling global grain stockpiles brought about by the conversion of millions of hectares of the North American and European corn belts from food to biofuel production in the early 2000s, caused convulsions in the market for agricultural commodities. On top of this, successive years of global-warming-induced droughts, flooding and wildfires in some of the world’s breadbaskets contributed to the depletion of grain reserves.

Perhaps the most significant factor of all was changing consumption patterns in China and other newly prosperous Asian countries. Whereas for centuries the majority of people in these countries had survived on overwhelmingly vegetarian diets, appetites for grain-intensive meat—especially pork—were exploding in tandem with their new-found wealth, creating rising demand at a time when supply was under pressure.

In wealthy countries where people spend an average of just 10 to 15 per cent of their weekly income on food, the effect was not dramatic. The big supermarket chains were able to protect customers by reducing spending on marketing and packaging—which, in the rich world, accounts for the lion’s share of food prices. In several import-dependent poor countries, however, where up to three quarters of many people’s weekly incomes go towards food, what were quickly termed ‘food riots’ soon began to erupt. In 2008, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Senegal and Somalia all saw mass street protests at the threat of hunger the rising food prices triggered; there were also food riots in countries as diverse and geographically dispersed as Indonesia, Mexico, Haiti and Yemen.

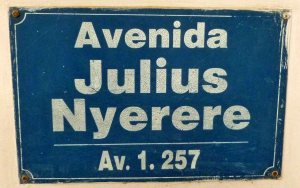

In early September 2010, while on assignment for a British newspaper in Mozambique, I witnessed a food riot first-hand. For months prior to this second round of food-related disturbances, the government had absorbed the increased cost of wheat imports, keeping retail wheat prices artificially low. As a result, the price of the ubiquitous fist-sized bread rolls—the staple of urban Mozambicans’ diet—remained unchanged. But, on the day I arrived in the capital, Maputo, the government’s wheat subsidy ended, and the street price of bread rolls increased overnight by a  third. This led to clashes between protestors and police along the city’s principal artery, Avenida Julius Nyerere, not far from the hotel where I was staying.

third. This led to clashes between protestors and police along the city’s principal artery, Avenida Julius Nyerere, not far from the hotel where I was staying.

Naïvely, I had strayed down the avenue, curious to get a look at what was happening. An anarchic scrimmage of bodies sprinted in every direction like shoals of fish chasing plankton. The smell of burning rubber singed the air, while some distance off a volley of gunshots pierced a metronomic chant, the meaning of which I could not understand. As I inched my way slowly towards what sounded like the heart of the action, a local shoe seller stopped me and explained how dangerous the situation was, that the city was like tinder. Heeding his advice, I returned to my hotel abruptly, and instead watched CNN rolling footage of the scene on Avenida Julius Nyerere, where a reporter in a Kevlar vest animatedly described the shooting dead by police of ten people during the morning’s rioting, including two children caught in the crossfire on their way home from school.

Representatives from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and senior diplomats from the EU, the US and other G20 countries have convened in Rome, in Dakar, and in Doha for high-level summits on the state of the world’s ‘food security’. In mid-2008, amid fears that some countries would start hoarding food supplies, the Dublin-based environmental think-tank Feasta urged the Irish government to draw up an emergency food plan in the event of Irish stocks running dangerously low. “There’s probably not a week’s supply of food for everyone here in Dublin, let along the country. The shelves would empty of food very quickly in the event of an emergency,” Bruce Farrell of Feasta told an Irish Independent reporter in July 2008. “We’ve seen food riots around the world, but it could easily happen here.” The then Minister of State for Food Trevor Sargent promised to outline a ‘food security roadmap’ in his annual review of farming policy, telling the Dáil in July 2008, “Ireland now faces a challenge as Britain experienced during the Second World War, when its government realized that there was a clear need for food security. They went from being 120 days self-reliant for food to 160 days.”

The cost of soya on commodity exchanges from Chicago to Bombay to Tokyo has doubled since the first price spike, those of corn and wheat have tripled, and that of rice has quintupled. After a small fall-off during the global recession in 2009 and 2010, prices inched back towards 2007–8 levels throughout 2011. Following a late surge in the final quarter of the year, the FAO’s Food Price Index recorded slightly higher prices in 2011 than peak prices last seen in 2008.

Against this background, it is easy to see why investors have been so interested in agricultural land: gain control of the ultimate source of these basic staples, the land, and you go some way towards grabbing a share of the ever-more-lucrative soft commodities market. For much of 2008 and into early 2009, Daewoo Logistics, the South Korean industrial giant, negotiated with the government of Madagascar to lease 1.3 million hectares—half Madagascar’s arable land—in order to grow corn and palm oil and send it back to South Korea for processing. Widespread street protests against the deal soon escalated, with the support of the main opposition leader, Andry Rajoelina. In March 2009, with the backing of military generals, Rajoelina installed himself as the country’s caretaker president. In his first act as president, Rajoelina axed the contract Daewoo was on the verge of signing. Had the Daewoo deal gone through, it would have been the single biggest transfer of African land to a foreign interest since the beginning of the continent’s independence struggles in the 1950s.

The Daewoo deal did not go through, but the scale of agricultural-land transfers in recent years has been dramatic. The World Bank’s 2010 report found that between October 2008 and August 2009 alone, some 60 million hectares of farmland—an area almost the size of France—transferred ownership at a cost of $100 billion. Seventy per cent of these deals took place in sub-Saharan Africa, the report found, where the outright purchase or lease price per hectare of land is the world’s cheapest. The Oxfam report cited research by the Land Matrix Partnership estimating that 227 million hectares—equivalent to the land area of western Europe from Norway to France, and from Switzerland to Ireland—“have been sold, leased, licensed, or are under negotiation in large-scale land deals since 2001, mostly since 2008 and mostly to international investors”.

Among the most prominent investors to date have been sovereign wealth funds and parastatal companies from China and oil-rich Arab princedoms. The rising cost of food caused Qatar’s food import bill to rise from $8 billion in 2002 to $20 billion in 2007—the country suffers severe water shortages amid spreading desertification, with only 1 per cent of its land suitable for farming. In an effort to gain more control over the national food supply, the Qatari government signed an agreement with Kenya in January 2009 to build a €3.4 billion port in Mombasa in exchange for the freehold over a 40,000-hectare farm in the Kenyan interior. China’s intense urbanization means arable farmland to feed its burgeoning population has been relentlessly squeezed in the last two decades. In one deal concluded in June 2008, China acquired a ninety-nine-year lease on a 101,171-hectare farm for rice production in Zimbabwe.

Phil Heilberg, a former partner with AIG, now owns a half a million hectares of savannah in South Sudan. Heilberg’s official partner in the venture is General Paulino Matip, whose local militias hold serious clout in the countryside around Juba. In the 1990s Human Rights Watch accused Matip of brutally clearing southern villages to make way for oil drilling. “This is Africa,” Heilberg unapologetically told Rolling Stone reporter McKenzie Funk when asked about his relationship with Matip. “The whole place is like one big mafia. I’m like a mafia head. That’s the way it works.”

The global land rush has not gone unnoticed by Irish investors. An Irish-backed investment vehicle, Fondomonte, purchased three farms totaling 12,000 hectares in Argentina’s Patagonian steppes in 2006 for €41 million. But just days ahead of a key January 2012 vote in the Argentinian parliament designed to limit foreign ownership of landholdings to 1,000 hectares, Fondomonte flipped its holdings to Saudi Arabia’s biggest food company, Almaria; the Irish Times put the value of the sale at €65 million. It would appear Fondomonte was keen to exit Argentina following growing unrest among local farmers over mounting concentration of the farm belt in the hands of a few foreign companies. In response, President Cristina Kirchner proposed a bill to cap the size of foreigners’ land holdings; it is widely expected the Senate will pass the bill.

In September 2011, UCD’s Michael Smurfit Business School hosted the inaugural Africa–Ireland Economic Forum. A partner from the consultancy firm McKinsey delivered the findings of the firm’s latest report—Lions on the Move: The Progress and Potential of African Economies—to an audience of over a hundred Irish business leaders. The report outlines how the continent ‘boasts an abundance of riches’, with land perhaps the most under-utilized of all of Africa’s natural resources. Of the total global stock of fallow land, 60 per cent is in Africa, the report notes, making the continent ‘ripe for a green revolution’.

Another driver of international investment in African farmland has been the growth of the biofuels industry. As concern over global warming and oil supplies intensified through the early 2000s, calls to develop alternatives to petroleum grew more urgent. Momentum gathered behind biofuels—that is, fuels made from crops (such as wheat, corn and sugarcane) that when fermented produce ethanol, or else from plants (such as sunflowers, rapeseed, flax and jatropha) that when pressed produce oils or fats that can be refined into bio-diesel. The Bush administration introduced generous subsidies encouraging American farmers to grow corn for ethanol rather than food in February 2007, promising that biofuels would supply 24 per cent of the nation’s transport fuel by 2017. The EU introduced a biofuel mandate in July 2009 requiring EU member states to blend all petroleum sold at forecourts with at least 10 per cent biofuel by 2020.

In September 2010 a World Bank report noted that the market created by US and EU biofuel policies meant there was a danger energy companies would now eye up farms, meadows, wetlands and rainforests in the same way they would a potential oilfield. Biofuel production has caused alarming rates of habitat destruction in Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia and a number of sub-Saharan African countries. Friends of the Earth has called for a phasing out of biofuel subsidies and demanded a moratorium on all biofuel production until such time as the technology for processing ‘second-generation biofuels’—the term used to describe biofuels derived from biomass residues and wastes as opposed to crops and plants—is properly developed and widely available. The carbon footprint of first-generation biofuels is little better—and in some cases even worse—than that of traditional fossil fuels, they argue, and the shift in land use has set up a competition between cars and people, between fuel and food; hybrid-powered motorists guzzle biofuels in the rich world while peasants in poor countries struggle against hunger, malnutrition, starvation.

The IMF suggested that biofuels were responsible for 20 to 30 per cent of the 2007–8 food price hikes, while an internal World Bank document leaked to the Guardian in July 2008 put the figure at a dramatic 75 per cent.

Marumbo, a village one hundred kilometers south-west of Dar es Salaam in Kisarawe district, has no running water, no electricity, and no cars, but it is neither primeval nor particularly remote. Upon my arrival, village chairman Adam Kipanga greets me warmly as he fields a call on his mobile phone; and a moment later, as I sign the visitor’s book in the community hall, I see I’m not the first journalist to pay the village a visit in November 2011. The ledger’s entry for 5 November shows that a Tanzanian television crew were here just three days earlier, while a few lines up, someone whose signature I cannot make out has written, in bold, ‘Guardian’ under the column for ‘Company’, followed by ‘King’s Place, London’ under the ‘Address’ column.*

Kipanga—middle-aged, rail-thin, wearing a red fez—leads the translator, Marwa, and myself to one side as the photographer who has been sent to accompany me instructs the villagers to pretend she’s not there taking photographs of them. Kipanga wants to explain to me Marumbo’s topography, why its lands are unusually ‘sweet’. The village’s land is bisected by the Rufigi River. When the Rufigi’s banks overflow each year, the spill rejuvenates the flood basin, leaving the plain larded in layers of loamy topsoil when the waters retreat. And perhaps the land’s sweetest feature—a feature that distinguishes it from other fertile plains in nearby Mozambique, Burundi, Congo and Uganda, all of which have witnessed vicious civil strife in recent decades—is that it is mercifully clear of landmines.

In early 2008 a local government official, Athumani Janguo, convinced Marumbo and ten other villages along the northern edge of the Kisarawe plateau to transfer use-rights over their farmlands to a British company, Sun Biofuels Ltd. In exchange for their land, Janguo told villagers they would receive a payment of 10,000 shillings (approximately €50) per acre they transferred to the company, as well as be offered steady work on the plantation—which would cultivate Jatropha curcas, a non-edible flowering shrub, for bio-diesel. As a further incentive, Sun Biofuels promised each village that handed over its lands a new school, a dispensary, running water and electricity, along with an improved road infrastructure throughout the district. After rounds of discussions headed by the eleven village chairmen, the villagers agreed the Sun offer would benefit the area. In May 2008, villagers signed a document agreeing to the transfer of their lands; since most heads of household in Marumbo are illiterate, in instances where a written signature could not be provided, thumbprints sufficed, Kipanga recalls.

The eleven villages were by any measure impoverished—they would not have accepted Sun Biofuels’ modest offer otherwise—but since that day in May 2008, Kipanga says, the quality of life in all of them has been in decline. Having secured the land, he says, Sun Biofuels quickly reneged on important parts of the agreement. For those hired as laborers on the plantation, wages that were agreed at 2,500 shillings a day were paid at half that; compensation was only ever paid for one or two hectares of land, regardless of the size of the plot villagers transferred; and as for the roads, water pumps and other amenities the villagers had been promised, not a single one ever materialized. The plantation shut down suddenly in October, Kipanga says, and all employees were fired on the spot.

Where exactly things went wrong for Sun Biofuels is difficult to say. As recently as April 2010, the Biofuels Digest reported that the company was planning to recruit an additional 1,100 workers to help with the jatropha harvest, while the company’s long-term ambition was to increase its land holdings in Kisarawe fourfold. On 31 October 2011 the trade paper reported the shutdown of the Kisarawe plant, with company officials citing problems finalizing a financing package as the reason behind the closure.

In the early days of the biofuels boom, Jatropha curcas was billed as having the capacity to yield up to ten times more vegetable oil than other biofuel plants; better still, it required only minimal water and needed little tending, thriving on marginal soils in arid conditions.

In 2007 Scientific American lauded the plant as ‘green gold in a shrub’. But these claims originated largely from controlled, small-sample scientific trials; the plant has not fared well when grown on a large scale in the tropics of sub-Saharan Africa. A December 2010 investigation by Friends of the Earth—Jatropha: Money Doesn’t Grow on Trees—cites several failed ventures. In 2008 BP pulled out of its 50,000-hectare joint venture in Swaziland with a UK biofuels company, D1 Oils. Returns on the jatropha plantation were conservatively described by a D1 Oils executive as ‘disappointing’—the company’s share price fell from 500 pence in early 2005 to below 6 pence in November 2010. In 2009 Sweden’s BioMassive declared bankruptcy after investing heavily in jatropha plantations in Tanzania; while a similar fate befall the Tanzania operations of Dutch company BioShape in 2010.

Good yields and high returns were only ever found on plantations where plants were highly dosed with expensive pesticides, heavily watered, and grown in good soil. “The idea that jatropha can be grown on marginal land is a red herring,” Harry Stourton, Business Development Director of Sun Biofuels, told Reuters following the Friends of the Earth report. “It does grow on marginal land, but if you use marginal land you’ll get marginal yields.”

With the photo shoot over, we join a dozen or so former employees of Sun Biofuels seated in the shade of a baobab tree, the village center. Kneeling down beside a young man named Burton, Kipanga lifts the left leg of his trousers, revealing an oval-shaped rash running the length of his tibia. Beside Burton sits a young woman, Salma, and Kipanga tells me to study her eyes: they are watering freely, inflamed, glazed-looking. Next to her is the oldest man in the group, Aadil, and Kipanga asks him to describe his problem. “I was spraying the plants for three years, every day, and now I fear I am infertile,” Aadil says. “I cannot service my wife the way I used to.”

None of the workers were given protective clothing or eye goggles while spraying jatropha with chemicals, Kipanga says; and this is why many of his fellow villagers now suffer these health complications.

To indicate just how costly the deal with Sun Biofuels has been, Kipanga points towards a cluster of mud huts dotted on the horizon: the village of Maneromango, whose lands fell outside the boundaries of the 8,000-hectare plot Sun Biofuels identified as suitable for its plantation. Maneromango recently harvested a bumper crop of maize, cassava and sugar cane from small plots carved out of the savannah. Fallen coconuts and plucked cashews were sold at market, while fronds stripped from the abundant palms were used to re-thatch the roofs of mud huts. Alongside this, a steady source of charcoal used as cooking fuel was felled from Maneromango’s woodlands, which when transported and sold in Dar es Salaam boosted his neighbors’ cash incomes. Strain the eye—Kipanga is pointing his hand to the left of the huts—and a small number of milk-producing cattle can be seen grazing among the mangroves.

Through an accident of geography, Maneromango’s inhabitants have been spared the depredations of the biofuel industry; in Marumbo, meanwhile, people are beginning to go hungry for the first time in decades, Kipanga says. Before Sun Biofuels’ arrival, life in Marumbo was tough, with few employment prospects, a high disease burden, and low educational levels. But the extremes of the poverty spiral were mostly kept at bay through the livelihood the villagers earned from working the land. Now, with the plant closure, they have no wage incomes, nor do they have the subsistence safety net the land provided for generations. Sun Biofuels’ freehold lease runs for another ninety-four years.

Leaning his head towards mine, Marwa reminds me that time is pushing on. We have to be back in Dar before dark—highway robberies at night are common, apparently—so I should wrap up the interview.

I thank Kipanga and the villagers for sharing their story with me, and wish them luck resolving their problems. As we shake hands, Kipanga says, “We get many journalists here. How is speaking to you going to help us?”

The question stumps me. Journalists are usually the ones asking the questions. Looking at the ground, I mumble something about ‘awareness-raising’ and how telling the story of Marumbo might help prevent similar disasters from befalling other communities in the future.

As Marwa translates into Kiswahili, I think about the handful of stories that I have written about poor countries. All have followed a fairly standard methodology: parachute in to speak with the victims of a shocking injustice; pluck out a wrenching tale; then fly off home to package the story in a way that vaguely piques the interest of readers while they sip their morning coffee.

Waving goodbye as our Land Rover accelerates out of the village, I realize I will be attempting to recount the same sorry story of dispossession, abuse, exploitation that the Guardian came looking for, that Tanzanian television came looking for. By the time the tires roll onto the paved road again I’m already dutifully recording in my notebook ways I might frame Marumbo’s narrative so as to fit with what I know to be the expectations of the newspaper back home.

Two days later, early morning, and I’m meeting my driver in the car park of the Blue Pearl Hotel on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam, from where we are to drive five hundred kilometers west to Iringa, a small town in central Tanzania. I’m early—I was anxious about sleeping through my alarm clock so kept waking through the night—and wander into the hotel vestibule to order coffee. Again I find myself among well-dressed people with name tags swinging from their necks. Hanging over a doorway manned by armed guards and a metal detector, I see a poster: “Tanzania Agriculture and Food Security Investment Plan (TAFSIP)/High-level Business Meeting/Blue Pearl Hotel, Ubungu Plaza/10–11 November 2011”.

By now a seasoned conference-raider, I help myself to a coffee from a trestle table at the side of the room and leaf through a brochure for the meeting. I’m surprised to learn that President Jakaya Kikwete is today’s keynote speaker. Marwa told me a probably apocryphal story in the Land Rover about Kikwete on the return journey from Kisarawe, by way of explaining why foreign companies can so easily secure contracts for large land tracts without much regard for due procedure. Kikwete is Muslim, Marwa told me, and as custom allows, he has the full complement of four wives. But Kikwete is a notorious womanizer and, not content with his harem, he has up to thirty girlfriends on the go at any one time, Marwa said, laughing.

The girls almost always come from prominent business or political families in Tanzania, and their fathers usually push them to go with Kikwete, he said: having a connection like this with the President is a valuable chip when bidding for a business contract or a government appointment. Marwa pointed out a plantation of sisal—a thick, fibrous plant used in making rope—that seemed to stretch for miles on either side of the highway. “That, it belongs to an Arab.” But the Arab in question would never have secured the land, Marwa continued, were it not for a former minister acting as local partner in the venture. “And the minister’s daughter,” Marwa said, looking back over his shoulder to me in the back seat, “she is one of the President’s girlfriends.” Breaking into a raucous fit of laughter, Marwa added: “So you see how my country works.” If you analyze the land deals involving foreign companies in the last three years, Marwa said, the common thread running through most of them is an influential local partner, and his even more influential daughter.

I later tried to confirm what Marwa had told me. As far as I could tell, neither the Tanzanian nor the international press have ever reported anything salacious regarding the President’s love life. All that an internet trawl unearthed is a number of bloggers pruriently likening Kikwete’s alleged affairs to those of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, Silvio Berlusconi and Bill Clinton. Some question Kikwete’s motives for appointing an unprecedented number of women to his cabinet—seventeen, up from four in the previous cabinet—when forming his new government in January 2006.

As for what Marwa said about malfeasance at the highest levels of government, the evidence for this is much more compelling. Since his election in December 2005, Kikwete has been widely condemned for appointing close friends to influential cabinet positions, and subsequently failing to hold them accountable when scandals have emerged. In 2006, in just one example, $116 million of treasury money earmarked for servicing Tanzania’s external debt disappeared, to later turn up in bank accounts belonging to twenty-two well-known Tanzanian companies with close government links.

The President asked those responsible to kindly return the money, and within one month over $60 million had been lodged back to government coffers. The names of those involved have never been disclosed and, despite widespread public anger over the case, no one has been charged.

A Wikileaks cable concerning British arms company BAE offers an even more damning indictment of the corruption running throughout Tanzanian politics. Though it has no air force, Tanzania’s military purchased a £29 million air defense radar system from BAE in 2001. An investigation by the Guardian in 2007 revealed that the arms trader made secret payments of £8.4 million to a senior Tanzanian official to secure the contract. The leaked US cable records a meeting between Tanzania’s chief anti-corruption officer Edward Hoseah and US diplomats in Dar es Salaam in July 2007. Then leading an investigation into what the cable calls the ‘dirty deal’, Hoseah “believed his life may be in danger” and that top-ranking Tanzanian politicians were ‘untouchable’. “He told us point blank… that cases against the prime minister or the president were off the table,” the cable notes, and that Kikwete ‘does not want to set a precedent’ by investigating allegations against his predecessors.

Dropping the brochure back onto the trestle table and finishing my coffee, I look up and recognize a face or two from the Grow Africa conference earlier in the week in the Kilimanjaro. One of those faces belongs to the man who asked me to leave the Grow Africa forum. As I brush past his shoulder on my way out the Blue Pearl’s main doors, I catch a glimpse of a logo printed along the bottom of his swinging name tag. USAID, the large type reads. The development agency’s strapline is underneath: from the American people.

On 5 May 2011, the Economist—whose editorial stance is firmly supportive of free trade and globalization—published a story about what it did not hesitate to call ‘land grabs’ in poor countries. “When land deals were first proposed,” the piece states, “they were said to offer the host countries four main benefits: more jobs, new technology, better infrastructure and extra tax revenues. None of these promises has been fulfilled.” The piece concludes: “What makes land grabs unusual is their combination of high levels of corruption with low levels of benefit.”

So Oxfam and the Economist are broadly in agreement—and yet, far from being a quiet conspiracy between rapacious international businesses and corrupt local governments, the phenomenon of outside investment in African agricultural land is actively supported by the agricultural development agency of the African Union, which is in turn actively supported by the international development agencies of a number of prosperous Western countries.

The Grow Africa Agricultural Investment Forum at the Kilimanjaro Hotel, I learned subsequently, was organized by the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Program (CAADP), an African Union-supported initiative to reform the agricultural sector in twenty African countries; the stated aim of the forum was to ‘strengthen new agricultural growth initiatives in Africa’ and to give ‘private-sector partners’ an ‘opportunity to have direct discussions with country teams on the investment opportunities available’. A listing of the forum on the website of the Global Donor Platform for Rural Development specified that queries concerning the forum should be emailed to Jackie Claxton, a Trade and Private Sector Advisor at USAID.

According to a draft agenda, the opening day of the forum began with a morning plenary on ‘Accelerating Investment in Agriculture’. After lunch, in bespoke ‘breakout sessions’, a ‘private sector coach’ was to be assigned to each participating country to help achieve clarity on what they need to do ‘in order to be ready for May 2012 deal-making’. The purpose of the evening slot, scheduled for 5 p.m.—around the same time I wandered into the Kilimanjaro marquee—was to ‘re-energize participants’ and offer a ‘recap of milestones’. Day two offered a similarly hectic itinerary of plenaries, keynotes and breakouts.

Much of CAADP’s energy of late, critics such as the Oakland Institute, Global Witness and the International Land Coalition complain, has been directed towards preparing the ground for private investors in African agriculture through facilitating the privatization of land. A recent report from the California-based Oakland Institute details how USAID and its counterpart development agencies from the UK, Sweden and Germany have been putting pressure on CAADP and other influential African bodies to make land available for private investment.

There was no room in the Grow Africa forum agenda for speakers who took a less sanguine view of such investment. Towards the end of my visit to Tanzania, I met Marc Wegerif, Oxfam’s Economic Justice Campaign Manager for the East and Horn of Africa, in an Indian restaurant close to his office on the Msasani Peninsula, one of Dar es Salaam’s wealthier suburbs. Wegerif, who had helped to organize my visit to Kisarawe, had no idea the Grow Africa forum was even happening until I told him about it after the fact. He was perturbed that the Tanzanian Ministry of Agriculture, with whom he works closely on many land issues, would not see fit to include a partner like Oxfam in such an event. “We’ve published research papers on this, shared them with government,” he told me. “And we’re the only ones in the country with anything like a functioning land database.”

I rummaged in my bag and fished out the Grow Africa notebook I had picked up inside the marquee. “Have a look at this,” I said, sliding the notebook across the table.

Wegerif’s eyebrows arched as he studied the notebook. He explained to me how Oxfam launched a campaign last year called Grow, whose aim was to challenge what the agency sees as deep injustices within the global food system. The cover of Oxfam’s Grow brochures, Wegerif told me with a wry chuckle, featured the word ‘grow’ with a tiny green shoot sprouting out of the ‘o’; beneath this was a photo of a pair of callused hands, holding a bushel of grain. “Now they’re even stealing our logo,” he said, shaking his head.

David Ralph is a freelance journalist and writes on social affairs for the Irish press. David Ralph recently completed a PhD in return migration at the University of Edinburgh.