PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Winning Hearts, Minds, and Independence

How the United States Approached Post-Colonial Africa

It was midnight on October 9, 1962, in Kampala, Uganda—the former British colony at the source of the White Nile on the shores of Lake Victoria. The Namboole National Stadium was full. Katharine, Duchess of Kent, represented the British Crown and presided over the lowering of the Union Jack and the raising of the red, yellow, and black flag of the newly independent Republic of Uganda. A high-level delegation from Washington featured the administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), accompanied by a bipartisan congressional group. As a very junior Foreign Service couple, my wife and I were thrilled to witness history in the making.

Between 1955 and 1965, 15 French and 10 British colonies in sub-Saharan Africa achieved independence. At the time, I volunteered to specialize in African affairs in the U.S. Foreign Service because I was enthusiastic about the challenge of conducting diplomacy toward these new sovereign entities. Additionally, several of my colleagues and I were fascinated by a U.S. policy that we considered surprisingly rational. After several heated debates in the National Security Council in 1957, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower decided that the United States would do its best to keep the Cold War out of Africa. In fact, at the final National Security Council meeting about Africa, Eisenhower set the tone of Washington’s outreach to the newly independent states by saying, “We must win their hearts and minds.”

After each new African country declared independence, the United States established major bilateral aid programs in short order. As the Ugandan Embassy administrative officer in Kampala, I was responsible for finding housing for 50 new USAID experts involved in health, education, infrastructure, agriculture, and urban planning. They were all assigned as advisers to the different government departments to help plan new investments financed by the international donors. For all of us involved in the process, it was a heady experience.

And as we in the U.S. diplomatic community focused on development initiatives, the new African heads of state—the founding fathers of newborn nations—shifted their focus from struggles for independence to the challenges of governance. And it was here, in this early phase of new U.S.-African relationships, that we discovered a wide discrepancy between their priorities and ours: U.S. diplomats looked for rapid ways to reduce poverty and stimulate sustainable economic growth, while African leaders concentrated on safeguarding their fragile sovereignty from international predators, maintaining internal stability in an environment of tribal and ethnic jealousies, and ensuring that their own political families were taken care of.

The first generation of postcolonial African leaders made economic and political decisions that could not have been more damaging to what the United States and other Western industrialized nations were trying to help them accomplish.

In the economic sector, African leaders took advice from advisers from the U.K. Labour Party and the French Socialist Party. This led to the nationalization of many African private sector enterprises in order to jumpstart development. Africa’s new leaders took over thousands of privately owned companies and sought to use these new properties to reduce unemployment—usually at the expense of making a profit and pursuing economic growth. In Uganda, for example, the national airline had three aircraft that served the East African region quite reliably. After nationalization, the payroll increased from 300 to 5,000, with no increase in business. Throughout Africa, the nationalized companies suffered from similar surplus employment, and therefore began to hemorrhage money. This required government subsidies to keep the enterprises alive, taking resources away from health services, education, and infrastructure maintenance. Before long, many burgeoning African nations faced a downward economic spiral that fed upon such poor decision-making.

In the political sector, Africa’s founding fathers inherited French and British parliamentary systems with multiple political parties and clean elections. After an initial round of elections and parliamentary debates, however, many of these leaders decided that Western-style democracy was not compatible with African traditions. Western democracy, they determined, was a cultural adversary. African democracy, they argued, is based on consensus. Issues are discussed slowly and calmly, with consensus emerging eventually. The intellectual leaders of this political philosophy were mainly among the English-speaking leaders, especially Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. The cult of consensus building eventually gave rise to the African one-party state. By 1975, 35 out of 41 African countries had rewritten their constitutions to establish the party of the independence movement as the only legally authorized political party.

These single monopolistic parties incorporated everything required to run a viable state: political control, oversight of civil society, and command of media (and in some cases, organized religion). What few independent media outlets existed at independence came under government ownership quickly. These new monopolistic parties established their own youth movements, women’s movements, bar associations, chambers of commerce, and virtually all other aspects of civil society. In the Republic of Zaire (now Congo), the party co-opted a prestigious Protestant pastor to be the movement’s “coordinator of religious affairs.” Needless to say, these political parties acted as parallel governments where elections would have otherwise taken place to determine national and local leadership. Instead, these systems led to massive corruption and the suppression of vocal opposition elements. The embryonic democracies that existed for a short period after independence were invariably replaced by authoritarian systems.

The myopic decision-making processes used by Africa’s new dictators made negative economic growth inevitable and devastating. Many, however, were able to hide behind the worth of their agricultural and natural resource exports. By 1975, however, Asian and Latin American commodities invaded the markets, plunging much of Africa into economic freefall. As Africa’s downward economic spiral unfolded over a 15-year period, the United States watched in silence. Washington had a policy that gave primacy to African sovereignty—nations were not to be criticized for their policies, as doing so would risk accusations of neocolonialism. As with the policy to exclude Africa from the Cold War, the decision to avoid second-guessing African leaders was taken by the Eisenhower Administration in 1957 on the advice of Vice President Richard Nixon, who had traveled widely in pre-independence Africa. Thus, aid agencies and government officials tasked with assisting new African nations in their postcolonial periods ended up saying nothing as policies began to crumble. This approach came back to haunt both us and them. Ironically, the first U.S. administration that had to cope with this failed policy was that of President Nixon, who saw congressional support for aid to Africa beginning to weaken. Nixon’s response was to shift most of the aid to Africa toward direct support for poor people living in rural areas under a policy entitled Basic Human Needs.

TEETERING ON COLLAPSE

During my career as an Africa specialist in the Foreign Service, I was able to have intimate conversations with many of Africa’s first-generation leaders. In my experience, virtually all of them had other items on their priority list aside from raising their populations out of poverty. With the exceptions of Cote d’Ivoire’s President Felix Houphouet-Boigny and Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni, all of Africa’s first- and second-generation leaders were fixated on cementing their political power and tribal loyalties.Houphouet, who himself was a farmer, made sure that Cote d’Ivoire’s growers were well compensated for their cocoa and coffee. Museveni had a university education and believed in protecting private property. But even these two enlightened leaders found themselves sponsoring destructive surrogate wars against their neighbors in order to bring about regime change.

In 1990, Houphouet decided that President Samuel Doe of neighboring Liberia, an uneducated army sergeant who had taken power in a military coup, was a disgrace to West Africa. With the help of eager collaborators like Libyan leader Muammar al-

Qaddafi and Burkina Faso President Blaise Compaoré, Houphouet sponsored a Liberian rebel movement headed by an exiled politician named Charles Taylor. What was supposed to be a swift ninety-day takeover turned into a seven-year war of great destruction from which Liberia has still not fully recovered.

Also in 1990, Museveni began to fear the high-level presence in his army of senior officers from the ethnic Tutsi refugee community that had been living in Uganda since 1961. This community of about 250,000 persons had run away from pogroms and ethnic cleansing in its native Rwanda. The “foreign” Tutsi community was generally resented by the indigenous Ugandan majority because of its high success in school, business, and the professions. Museveni decided to provide military and logistical support to a Tutsi insurgency in Rwanda designed to topple the regime there so that the refugees could return. This insurgency led directly to the infamous Rwandan genocide in June 1994.

As African leaders faced strong political constraints from the World Bank when it came to domestic economic policies, some shifted their main focus to foreign policy, where they had complete freedom of action. Senegal President Leopold Sedar Senghor, for example, tried to play a role in efforts to prevent Middle Eastern nations from isolating Egypt in the wake of its peace agreement with Israel, brokered by United States President Jimmy Carter. Senghor engaged in intensive diplomacy within the Conference of Islamic Nations, of which Senegal was a charter member. He had only limited success, but raised his country’s international profile.

Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda helped the United States bring about an end to the Angolan civil war in 1991, as did Zimbabwe president Robert Mugabe in the Washington-led conflict mediation efforts in Mozambique a year later. President Mobutu Sese Seko, of the nation formerly known as Zaire and later the Democratic Republic of Congo, regularly asked me for “walking around” money so that he could curry influence within his immediate neighborhood. With a limited amount of our assistance, Mobutu was able to help stabilize politics, at least temporarily, in the Republics of Chad and Togo, and he established the Association of Great Lakes Nations, which remains active today.

In my many conversations with these leaders, foreign policy was almost always the main topic. Because of the failures of their economic policies, the African leaders I talked to felt more comfortable discussing international issues. In addition, they wanted to show the big powers that they could carry some weight in the quest for regional stability.

ON THE UPSWING

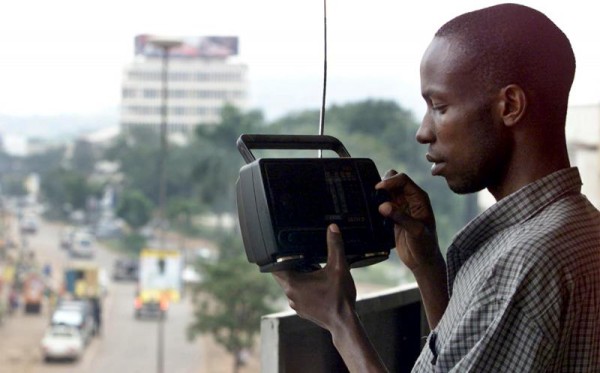

With the second and third generations of African chiefs of state now in power, things have changed somewhat for the better. Many countries in the region now host multiparty democratic systems, even if the quality of these democracies is fragile. The number of privately owned free media outlets has grown. There are very few African countries today that do not have privately owned newspapers, radio stations, and TV outlets competing with government media. The Voice of America, the British Broadcasting Company, and Radio France all broadcast from local FM stations. Africa’s private sector is making a cautious comeback, thanks in no small part to the prodding of the United States and the World Bank. State-owned Chinese companies have entered African countries with major investments, mainly in primary commodity sectors, with mixed impact. Chinese efforts have built useful infrastructure staples, but are not looking to build local governance capacity.

There are signs in some countries that sustainable development can take hold, provided additional reforms are instituted. These nations can achieve growth by ensuring that the rule of law is upheld, that money from diaspora communities can make its way back home through sound investment opportunities, and that cross-border trade barriers are eliminated. In this regard, I am particularly optimistic about Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana, and Kenya, where African private enterprise is starting to show confidence.

Nigeria, despite its dysfunctional political system, has a strong and independent judiciary that gives both domestic and foreign investors a sense of security for their contracts. In Senegal, a young new head of state, Macky Sall, is focusing his government on opening investment opportunities for the business community. Foreign investors are flocking to Côte d’Ivoire to take advantage of West Africa’s large francophone populations.

A more enlightened generation of African leaders is slowly moving to the fore country by country.

On the other hand, there are too many nations with significant potential that are still in the doldrums of mismanagement and inefficient rule. Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and South Africa could benefit greatly from economic and political reform; these nations are large enough to host sustainable development initiatives, but such efforts are low on the priority lists of their leaders. Producing two million barrels of oil per day, Angola has wasted a decade of high oil prices through mismanagement and corruption. There is very little to show for all that wealth in terms of poverty reduction. Angola needs a heavy dose of transparency and honest management of revenue. Exactly the same holds true for the Democratic Republic of the Congo, whose copper production of 600,000 tons per year is showing very little result in improved health, agriculture, and education. South Africa is the big disappointment because it enjoys a true democracy and has a strong industrial base. Unfortunately, the ruling African National Congress has fallen into corruption and is neglecting the education and infrastructure needs of millions of poor African citizens with great expectations. These three nations should be leaders in the development of the entire continent. Unfortunately, their outlook is bleak if they continue to govern with little regard for their peoples.

A more enlightened generation of African leaders is slowly moving to the fore country by country, providing hope that the continent will continue to progress steadily and gain footing alongside other emerging nations around the world. Unfortunately, on top of their other problems, several African regions cannot escape the scourge of jihadist terrorism that has radiated out from adjacent Arab countries. It is in this aspect that the United States and donor states in Europe have paid the price for their failure to intervene politically with the first generation leadership.

Although Africa can now boast of several success stories, several nations in the region have failed to recover from their initial setbacks after colonialism, and remain vulnerable to terrorism. The education and development deficits seen in these nations have created generations of deprived Muslim youths who have become susceptible to jihadist brainwashing.

The Sahel region grapples with the extremist remnants of the Algerian civil war, calling themselves al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), who have destabilized the poor northern districts of Mali, Niger, and Nigeria. After end of the Algerian civil war in 2000, AQIM was a ragtag band of about 3,000 fighters who had refused amnesty. They sustained themselves through the trans-Saharan drug trade. But when Libya fell apart in 2011, they got a new lease on life by co-opting many of the African military mercenaries who had been working for Qaddafi and had fled back to Mali, Niger, and Nigeria. The European and American security establishments had neglected this vulnerable region only until the Libyan debacle made things very dangerous.

Around the shores of Lake Chad, the extremist group Boko Haram has caused significant damage to the populations of Chad, Niger, and Nigeria, receiving support from jihadist factions in anarchic southern Libya. Somalia battles against the al Qaeda franchise al Shabab without the benefit of a viable central government. Although the African Union has military forces in Somalia, and has reduced the group’s territorial control, it has yet to stop its terrorist attacks in neighboring Kenya.

WHAT’S AHEAD

The outlook for Africa’s future depends on overcoming the consequences of early mistakes made by their founding leaders. A number of African nations are on track to emerge as significant players in the world economy, both as producers and consumers. Gains in commodity markets have given rise to an emerging African middle class with disposable income—so much so that U.S. companies such as Citibank, the Ford Motor Company, General Electric, and Wal-Mart are entering Africa’s expanding consumer markets.

Current U.S. policy has emphasized support for private investment in Africa, and has provided hands-on assistance to African nations currently fighting against terrorism. Whereas Washington used to be reluctant to interfere domestically in African affairs, it now engages in very frank dialogue about good governance with this new leadership generation. U.S. President Barack Obama has been particularly strong in this arena. Obama feels uniquely comfortable speaking the truth to African power about how corruption and bad governance are cheating the African people. This was the President’s main message during his closed-door sessions with the African heads of state at the first ever African summit held in Washington in August 2014, as reported by representatives of the American private sector who had been invited.