PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Natasha Stallard in Entoto |

"We don't take sides; we help you see more sides."

Published:

PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Natasha Stallard in Entoto |

Multi-million dollar facility offers excellent views of Orion’s Belt – and opportunities to tackle climate change and famine

With its clear skies and closeness to the equator, Ethiopia is an ideal location for space exploration. Yet for a developing country facing its worst drought in 50 years, spending millions of dollars to look at the stars might, at first, seem frivolous.

“They call us crazy because they think we’re [only] exploring outer space and gazing at the stars. But they can’t see the bigger picture,” says Abinet Ezra of the Ethiopian Space Science Society.

Sitting in a roadside café near the Addis Ababa Institute of Technology, Ezra explains that the “bigger picture” means using space research to expand the economy, improve agriculture, fight climate change and create jobs.

The Ethiopian Space Science Society, which has recruited 10,000 members since being launched in 2004 by three aspiring astronomers, has recently opened east Africa’s only space observatory on the 3,200-metre summit of Entoto, overlooking Addis Ababa.

The multi-million dollar Entoto Observatory and Research Centre has become one of the prime places to view Orion’s Belt – which appears larger and more pronounced here than from other parts of the northern hemisphere.

The society wooed a series of government insiders and private donors, including the Saudi-Ethiopian billionaire Sheikh al Amoudi, to fund its research and pay for the observatory – although the government took over running costs in March.

With 10 million Ethiopians at risk of famine, this might seem extravagant. But government officials and space enthusiasts say the same thing: that space science is essential for the country’s development, whether using earth observation to improve agriculture or lowering the costs of communications through the launch of its own satellites – which it currently rents from other countries for inflated sums.

“It was our priority to convince the government – now they have been convinced,” says Dr Solomon Belay Tessema, director of the Ethiopian Space Science Society and one of its founding members.

Ethiopia. He remembers reading news of Yuri Gagarin’s launch into space in Amharic newspapers as a child.

The director explains how agriculture, water resources, telecommunications, education, healthcare and the economy all stand to gain from Ethiopia’s space science research. What may seem like a huge investment now will pay off in years to come, he says.

His own education is an example of the change the Ethiopian Space Science Society has lobbied for: with no postgraduate facilities in astronomy and astrophysics available in Ethiopia in 2008, Tessema travelled to Sweden to complete his PhD. He returned to his home country energised by the possibility that astronomy could serve “not just science, but all [of Ethiopia’s] 94 million people.”

Last year, 219 students applied for the 24 places on the Institute of Technology’s PhD program in astronomy, one of the five universities now teaching at a post-graduate level in the country. The society manages more than 60 space science clubs throughout the country’s school system.

“If someone studies here, they’re going to contribute to society. It’s a mechanism to control the brain drain,” the director says.

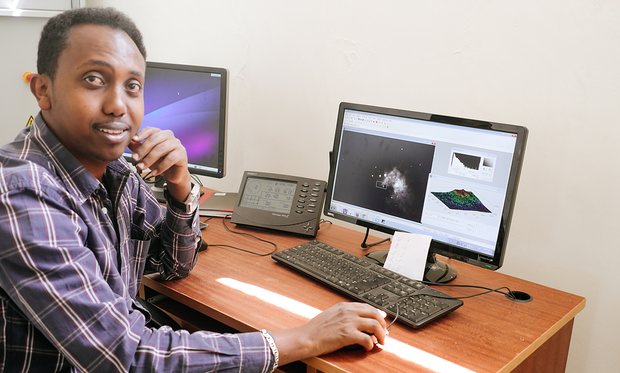

“We’re not looking for aliens,” says Ghion Ashenafi, a 24-year old electrical engineer during a tour of the observatory, as a group is led to see the twin German telescopes housed in Entoto’s two domes.

The complex is so new that the chairs in its digital library are still wrapped in plastic.

Ashenafi runs through a series of his favourite astro-photos captured by the telescopes: the moons of Jupiter, the two outstretched arms of the spiral M51 galaxy. A member of the predominant Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo church, Ashenafi talks about the uneasy meeting of Ethiopia’s new space exploration drive and its ancient religious beliefs.

“For me it’s about attitude. I always say God created everything. For me, science is a proof of God,” Ashenafi says.

Standing on a holy mountain in one of the oldest Christian countries in the world, the Ethiopian Space Science Society is often seen as a challenge to the church.

Astronomy is a particular bone of contention. Ethiopia’s long history of stargazing predates Christianity – a scholarly tradition tied to agriculture. Some historians argue that the first study of celestial bodies can be traced back to Ethiopia.

“If you look at a church or mosque, you see a dome-like structure. And if you look at an observatory, you see a dome-like structure too,” says Kelali Adhana, the board chairman of the Ethiopian Space Science Society.

He recalls his own love of the stars as a child. “Like any child that grew up in a rural area, we looked to the sky to tell the time – we didn’t have watches. I knew the stars by name, but only in the local language,” Adhana says.

The Ethiopian Space Science Society is currently working on a feasibility study to build a second observatory in Lalibela. One of Ethiopia’s holiest sites, Lalibela’s 12th century rock-cut churches are a feat of engineering that has long fascinated visitors – some believe they were built by angels, others by aliens.

The proposed state-of-the-art research centre has the backing of the International Astronomical Union, of which the Ethiopian Space Science Society is an official member, and the society believes that the dry climate and Lalibela’s 4,200-metre-high peaks have the same stargazing potential as the famous Atacama desert in Chile.

This international recognition, as well as a visit from Nasa administrator and former astronaut Charles Bolden in 2014, gives the Ethiopian Space Science Society extra motivation as it continues to lobby the government for research funding and support.

The society hopes to represent east and central Africa in the space science field, and applauds the work of South Africa as well as the Nigerian space agency. While development remains the society’s main aim, do they have plans to send an Ethiopian astronaut into space? “Of course,” says Ashenafi.

“But maybe not in my lifetime – there’s plenty of other work to do first.”