PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

The ‘Strategic Logic’ of Suicide Bombing

Uri Friedman |

An expert boils down the Brussels attacks to one word: territory.

In October 2015, two suicide bombers killed more than 100 people outside a railway station in the Turkish capital of Ankara. It was the deadliest terrorist attack in the country’s modern history, but it was also something more, something not fully appreciated at the time, according to Robert Pape, a terrorism expert at the University of Chicago: The U.S.-led military campaign against the Islamic State—a mixture of air strikes and support for local ground forces—had turned ISIS into a “cornered animal.” And the animal was lashing out.

The group’s suicide attacks in its sanctuaries of Syria and Iraq declined, displaced by complex acts of terrorism abroad: the Ankara attacks, followed by the October 2015 downing of a Russian plane over Egypt, the November 2015 Paris attacks, more explosions in Turkey, and most recently triple bombings, at least two of them suicide blasts, in Brussels. All have appeared meticulously designed to kill as many people as possible in countries that are all, to differing degrees, fighting the Islamic State. The question is: Why is the animal suddenly flailing about? Why are bombs going off in Brussels now?

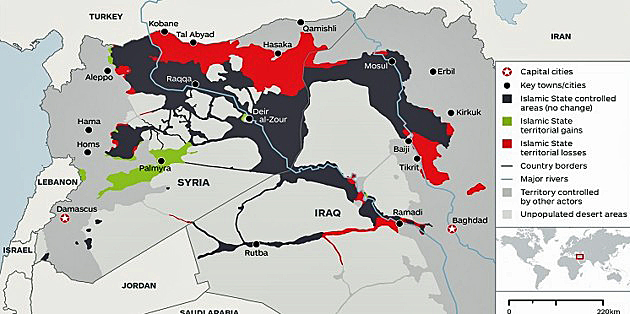

According to one recent estimate by IHS Jane’s 360, the Islamic State lost control of 14 percent of its territory between January and mid-December 2015, and an additional 8 percent in the last three months (in the map below, red represents losses, green gains, gray no change).

But if the occupation of territory spurs terrorism, why does it take the form of suicide terrorism specifically? Suicide attacks, Pape explained, are particularly well-suited to accomplishing two goals. One is “to coerce the target government to pull back its military forces, and suicide attacks kill more people—it’s the lung cancer of terrorism—than non-suicide attacks by a factor of ten.” The public will be terrorized by the scale of the carnage and the sinister nature of the suicidal act itself, the logic goes. Under pressure, their government will be forced to retreat from the territory that the terrorists desire.

Second, in the regions where terrorist groups operate, “suicide attacks are excellent against security targets to hold territory.” Those security forces—be they American or Iraqi or Sinhalese—are usually better armed and equipped than the terrorists. “Suicide attacks are a way to level that tactical advantage,” Pape explained.

“If you’re just going to go up against a tank with a handgun, it’s a lot less effective than some coordinated suicide attacks,” he continued. “That’s why, when there was a pitched battle for [the Iraqi city of] Ramadi last May, there were complex suicide attacks [by ISIS] used in coordination with other non-suicide attacks to basically seize and hold territory against an opposing force. That’s not something that we see in El Salvador with the [guerrilla group] FMLN [during the Salvadoran Civil War]. We don’t see that with the [Viet Cong] in South Vietnam [during the Vietnam War]. They’re not holding territory in a pitched way. … Suicide attack allows for more aggressive, coercive punishment and it allows for more aggressive territorial strategies.” While these strategic considerations have remained fairly constant across time and place, he says, what’s changed in the last 10 or 15 years is that in countries like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, suicide bombing has increasingly been used as a tactic to take and hold territory.

On Tuesday, ISIS justified its suicide attacks as retaliation against “the Crusader states” for “their aggression against the Islamic State,” adding that it had targeted “Crusader Belgium” in particular because it would “not stop targeting Islam and its people.” The statement had all the trappings of a religious message, but its essential argument echoed Pape’s secular thesis: Brussels was being targeted for the participation of Belgium, and European countries more broadly, in the anti-ISIS coalition. What if we take the jihadists at their word?

Uri Friedman is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where he covers global affairs.