PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

In Namibia: The People Have Voted, or Not…

Henning Melber

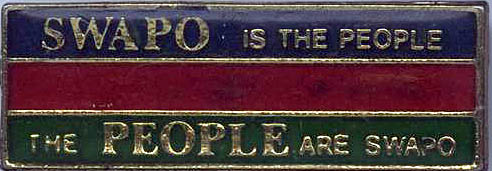

Namibia is now the arena of one-party dominance. This translates the slogan from the struggle days that “SWAPO is the nation and the nation is SWAPO” into the dominant if not exclusive political culture. While observers testify to free and fair elections, the latter seems to be a relative if not dubious call. The party is the government and the government is the state, which also keeps the electorate at bay.

President Geingob will not have an easy task. He might be the last president of the first generation—who joined the anti-colonial movement in its founding days and was in exile for more than a quarter of a century. Given the overwhelming majority secured by the party and the personal power vested in his office, it remains to be seen to which extent he translates the political success into a success story for the Namibians.

On 28 November [2014] close to 900,000 Namibians of a registered electorate of some 1.2 million (a bit more than half of Namibia’s total population, estimated at 2.3 million) voted in the country’s fifth parliamentary and presidential elections since Independence. The result was predictable, though the dimensions of the overwhelming dominance of the former liberation movement SWAPO did surprise. While SWAPO secured in every election since 1994 well above a two-thirds majority, this time the result crossed the 80% mark. The party’s presidential candidate Hage Geingob topped this by a whopping 86%.

Not that SWAPO was uncontested. Another 15 political parties campaigned for votes. Nine of these managed to secure in total 19 out of the 96 seats in the National Assembly for the next five-year legislative period, which starts with Independence Day on 21 March 2015. Such opposition is more divided than ever before and underlines its weakness.

Not that SWAPO was uncontested. Another 15 political parties campaigned for votes. Nine of these managed to secure in total 19 out of the 96 seats in the National Assembly for the next five-year legislative period, which starts with Independence Day on 21 March 2015. Such opposition is more divided than ever before and underlines its weakness.

President-elect Geingob, who also enters office on 21 March 2015, scored bigger than his predecessors Sam Nujoma and Hifikepunye Pohamba against eight other contenders from the minority parties. More than ever, Namibia’s political sphere will be the arena of a one-party dominance. This translates the slogan from the struggle days that “SWAPO is the nation and the nation is SWAPO” into the dominant if not exclusive political culture.

Undemocratic democracy: A question, which unfortunately cannot be reliably answered, is the extent to which parts of the Namibian electorate refused to vote. Over-ambitiously, the Electoral Commission of Namibia (ECN) had decided to use as the first African country in general elections electronic voting machines.

This did not only provoke suspicions that these could be manipulated. It also resulted in an embarrassing logistical and technological disaster. Reportedly, thousands of voters were unable to participate in the elections due to various hiccups; despite queuing often for most of the Election Day if not longer (some polling stations remained open until the next morning while voters waited throughout the night).

Strictly speaking, a considerable number of Namibians were denied their fundamental right to make a choice, which actually casts a shadow on the label democratic. While this might have not decisively affected the outcome, it makes it impossible to assess how many among the registered voters had actually made a political decision not to vote.

Voters’ participation around 72% seems high, but is actually low in comparison with previous parliamentary and presidential elections. If and to which extent this might be a warning signal, that in the absence of any meaningful and credible political alternatives part of the electorate decided to stay at home, will remain a matter of speculation.

President Geingob will on Independence Day 2015—21 March—move into State House with even more executive powers than his predecessors already held. The National Assembly adopted with the SWAPO majority against the opposition votes in late August 2014 not only the new electoral law endorsing the use of electronic voting machines—it is noteworthy that the law stipulates that a paper trail is required to visibly confirm for the voter the choice s/he made—only to realize afterwards that it was impossible to comply with the law in the absence of a tested technology allowing to do so.

It also voted for far reaching constitutional amendments, which consolidated the party control over state affairs even further. They add to the power of an already strong executive president. Namibia’s de facto one-party democracy will now be even closer to a one-person democracy, depending upon the degree to which the office holder is willing to use—or abuse—the presidential powers.

Already now the signs of democratic authoritarianism suggest that while the country fulfills all the formal criteria of a democracy (multi-party state, regular elections, democratic constitutional principles, civil liberties and a fairly independent judiciary combined with independent media and a freedom of speech), there is no level playing field.

While observers testify to free and fair elections, at least the term fair seems to be a relative if not dubious category. The only party having an efficient machinery and financial means (not least through massive donations from a private sector, which benefits from business with government and state) can mobilize accordingly. The equation that the party is the government and the government is the state is a powerful formula, which also keeps the electorate at bay.

While observers testify to free and fair elections, at least the term fair seems to be a relative if not dubious category. The only party having an efficient machinery and financial means (not least through massive donations from a private sector, which benefits from business with government and state) can mobilize accordingly. The equation that the party is the government and the government is the state is a powerful formula, which also keeps the electorate at bay.

Evidence of the unfair practices within such an environment was among others that SWAPO bought considerable time from the state owned Namibian Broadcasting Company (NBC) to transmit its final political star rally live via TV—as if a public broadcaster can be hired by political parties.

Unfinished business: But business as usual remains a risky endeavor. Protest at the grassroots is visibly growing over the abuse of power for self-enrichment of a tiny elite in government and state offices as well as the private sector linked to the party machinery by political or family connections (the terms ‘fat cats’ and ‘tenderpreneurs’ are common slang and have anything but positive connotations).

The massive social inequalities have hardly been reduced since Independence. Rather, next to the old elite benefitting from the Apartheid minority regime emerged a new elite, whose members prosper as a result of SWAPO’s selectively applied “affirmative action” (an euphemism for clientele relations of a patrimonial system). While political power changed, the class structure became only modified (and to some extent ‘de-racialized’), but not challenged in principle.

SWAPO’s slogan from the struggle days, “Solidarity, Freedom, Justice” (note the absence of equality) remained after the seizure of political power a hollow reminder of earlier days. Meanwhile, confronted with the increased and unashamedly greedy self-enrichment of the new elite, the frustration over the lack of delivery and hence the dismal failure to live up to the promises associated with Independence is growing among the ordinary people as well as in parts of the younger generation, including those politically active in SWAPO.

The party has also never been free of internal rivalries and factions, also fueled by ethnic and inner-ethnic power struggles. After all, given its dominance and control over the political and administrative spheres of society, the access to power and thereby to the troughs needs to be through the party machinery.

When moving into office, President Geingob has not an easy task. With 73 years of age he might be the last of the first generation in the highest office—who had joined the anti-colonial organization during its founding days and was in exile for more than a quarter of a century. While celebrated as a unifier (he is the first president to be who comes not from the dominant Owambo-speaking population group from the Northern region, which might explain the additional votes from other population groups), he has a lot on his checklist to achieve this goal.

Given the overwhelming majority secured by the party and the personal power vested in his office, it remains to be seen to which extent he translates the political success into a success story for the Namibians.

Henning Melber joined Swapo in 1974. He headed the Namibian Economic Policy Research Unit 1992-2000. His book ‘Understanding Namibia: The Trials of Independence’ has just been published with Hurst (London) and Jacana (Auckland Park). Henning Melber, Senior Advisor of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation and of the Nordic Africa Institute, Extraordinary Professor of Political Sciences/University of Pretoria and the Centre for Africa Studies/University of the Free State in Bloemfontein.

Henning Melber joined Swapo in 1974. He headed the Namibian Economic Policy Research Unit 1992-2000. His book ‘Understanding Namibia: The Trials of Independence’ has just been published with Hurst (London) and Jacana (Auckland Park). Henning Melber, Senior Advisor of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation and of the Nordic Africa Institute, Extraordinary Professor of Political Sciences/University of Pretoria and the Centre for Africa Studies/University of the Free State in Bloemfontein.