PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

No, South Sudan’s citizens want trials and need trials

David Deng | June 9, 2016 | African Arguements

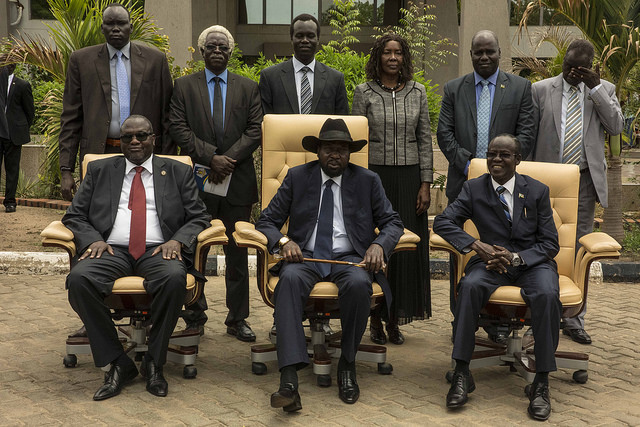

President Kiir and Vice-President Machar have warned against prosecuting war criminals, but South Sudanese know that justice is needed if long-term peace is to be viable

There’s a common saying in South Sudan that ‘When our leaders unite, they loot; when they divide, they kill.’ An op-ed published this week under the names of President Salva Kiir and First Vice-President Riek Machar provides further evidence of how these bitter rivals are to only too willing to cooperate when it suits their own personal interest. In the op-ed, the two leaders propose that South Sudan forgo the Hybrid Court provided for in the August 2015 peace agreement and instead establish a national truth and reconciliation commission that would provide amnesties to perpetrators of international crimes.

It should not surprise anyone that the two leaders of the recently-formed Transitional Government of National Unity would prefer to forgo criminal trials. Numerous reports from the African Union (AU), United Nations (UN) and international human rights organisations have documented atrocities committed by both sides in the conflict. In January 2016, a UN panel of experts on South Sudan found “clear and convincing evidence that most of the acts of violence committed during the war…have been directed by or undertaken with the knowledge of senior individuals at the highest levels of the Government and within the opposition”.

Gruesome accounts of war crimes and crimes against humanity have surfaced with disturbing regularity from South Sudan. The AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan, for example, documented an incident in which government soldiers raped a woman during fighting in Unity State in March 2014 before proceeding to cut off the arm of her three-year-old child and put it in her vagina. In another incident, the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) said that opposition forces massacred at least 287 people in a mosque in Bentiu on the morning of 15 April 2015. During a government offensive in Unity State in May 2015, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) documented instances of boys being castrated and left to bleed to death, girls as young as eight being gang-raped and murdered, children being tied together with their throats slit, and others being thrown into burning buildings.

In the face of these horrific acts, South Sudanese are becoming increasingly vocal in their demands for justice. In a recent survey by the South Sudan Law Society (SSLS), 93% of the 1,525 people we spoke to across the country said that individuals suspected of conflict-related abuses should be prosecuted in courts of law, and 83% of respondents supported the involvement of international justice mechanisms. Our research shows that South Sudanese are waking up to the short-lived nature of solutions that focus exclusively on placating perpetrators of violence and recognise the importance of justice and accountability to longer-term peace.

The August 2015 peace agreement provides an opportunity to begin addressing the unmet demands for justice among populations in South Sudan. In addition to the Hybrid Court, the agreement provides for a truth and reconciliation commission and a reparations authority. Taken together, these institutions provide an opportunity for South Sudan to start tackling impunity, address inter-communal grievances, and repair the harm that decades of war have done to society. Without the Hybrid Court, the governance culture that rewards those who wield violence to achieve their political (or personal) objectives while leaving the victims of those abuses to suffer in silence will continue unabated.

It is now upon the AU, which bears primary responsibility for the Hybrid Court, to move ahead with its establishment. Not only is the AU a guarantor of the peace agreement, justice provisions and all, but the AU’s own Commission of Inquiry also independently determined that sustainable peace is not possible without holding individuals accountable for atrocities committed during the conflict. Just last week, the AU gave victims of human rights abuses across the continent a glimmer of hope when an AU-backed court in Senegal sentenced Hissène Habré to life in prison for crimes against humanity he committed during his eight-year rule in Chad (1982-90). The AU should take advantage of this moment and put in place a framework for the Hybrid Court now, as it will take several years before the court becomes operational and begins trials.

[See: “The president is not an untouchable god”: Chad’s Hissène Habré sentenced to life]

The ultimate responsibility, of course, lies with political leaders in South Sudan. If building a nation is their life’s work, as the President and First Vice-President claim in their op-ed, they should retract their stated opposition to the Hybrid Court and recommit to implement the peace agreement in full. The logic that sees political leaders single-mindedly pursuing their personal interests when they’re together and wreaking havoc when they’re apart must be stopped if South Sudan is to retain its viability as a nation.

David K. Deng is research director for the South Sudan Law Society (SSLS), a civil society organisation based in Juba, South Sudan.