PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Has Eritrea’s self-reliant economy run out of puff?

A “go it alone” culture has long been central to Eritrea, including its economy. It is slowly opening up to foreign investment, but recent policies, especially a currency reform, mean many people are now struggling in what was already one of the poorest countries on earth.

In a dusty corner of the capital, Asmara, is a walled market. It assaults the senses as soon as you enter, for it deals in just two things: Chillies and metal.

Big chillies, medium-sized chillies and, fiercest of all, the tiny chillies, draw tears, itches and sneezes.

There is a deafening cacophony as old metal is bashed from rusty, useless scraps into shiny cutlery, hairpins, gates, gutters and religious artifacts.

Eritrean metal worker:

“I am rewinding the metal,” says a man as he bangs out a large serving dish from an old oil drum.

The market is basically a giant recycling centre and represents the country’s fierce spirit of “self-reliance”, a phrase I hear often in Eritrea.

This culture started during the 30-year war of independence from Ethiopia, when rebels produced almost everything they needed in underground factories, including clothes, shoes and medicine.

It endured after Eritrea won the war in 1991, with the country periodically expelling aid agencies, saying they promoted dependency.

Unlike most African countries, there is a lack of large UN and NGO land cruisers zooming around the place.

Although education up to tertiary level is free, young Eritreans are not free to pursue their own dream careers. They become locked into a system of obligatory national service, mainly in civilian roles, and have no idea when they will be released.

In the spice and metal market, a man proudly shows me a storage container he has made from broken bits of mirror and steel.

“I have been in national service for nine years. The pay is very low – less than $50 [£37]a month – so I supplement it by working here.”

‘Remittances plunging’

Eritrea came third bottom in the United Nations Human Development Index for 2015. Time and again, I hear similar stories of people doing two or even three jobs to make ends meet.

On the plane to Asmara, I meet a man who imports mobile phones, televisions and satellite dishes from Dubai.

“I have been in national service for 12 years. But I sort of ‘dropped out’ to become a trader.”

National service has another economic effect, as it is one of the main reasons so many young Eritreans flee their country for Europe, draining the country of much of its productive workforce.

However, if they get there safely, instead of dying in the desert or drowning in the sea on the way, many end up as “useful” members of the diaspora, sending money home.

In 2005, remittances were estimated to account for about a third of Eritrea’s GDP.

“However, that figure is plunging. The diaspora is now spending the money on helping people leave Eritrea instead of supporting relatives at home,” says one official.

The Eritrean authorities used to be quite happy for disaffected youth to leave, says a diplomat.

A potential threat to stability was out of the way, and they were likely to end up sending remittances.

But, the diplomat says, the country now faces a serious capacity shortage and is doing more to encourage them to stay.

Hagos Ghebrehiwet, the economic adviser to the president, says the amount paid to those in national service is increasing from about $50 to $130-$300 a month, depending on education levels.

Government ministers tell me they earn about $200 a month, plus some allowances.

How 40% of the money disappeared

Most of the complaints I hear in Eritrea are about the skyrocketing cost of living, plus chronic shortages of electricity and water.

Depending on their size, families receive a certain quantity of basic foodstuffs, such as cereals, oil and sugar, at highly reduced prices. But other items cost a lot. For example, a litre of milk costs more than $2.

Business people, including taxi drivers, shopkeepers and hoteliers, say their incomes have halved since a new form of currency was introduced at the end of last year in an attempt to control smuggling, the parallel market and human trafficking.

They complain that restrictions on imports and tight limits on the amount of money they can withdraw from banks are strangling their businesses.

Finance Minister Berhane Habtemariam says people were given six weeks to swap their old notes for new ones, at par.

“We had no choice. The coffers of our banks were literally empty. When people came to exchange their notes, they had to explain how they had earned the money.

“As so much of it was illegal, only 40% of the old notes were handed in, leading to a 60% contraction in the money supply.”

The introduction of the new notes has had an impact on the parallel market. The fixed exchange rate has remained at 15 Eritrean nakfa for $1, but Eritreans say they now only receive about 18-20 nakfa for the dollar on the unofficial market, instead of nearly 60.

It is very difficult to work out what is going on in Eritrea’s economy because the government does not release figures for its GDP and other key indicators.

“We have not given out any information about our budget for seven years because our enemies will use it against us,” says the finance minister.

Mines and fashion

Despite this secretive behaviour and the allegations of human rights abuses in the labour force, there are signs of growing interest from foreign investors.

Some have been in Eritrea for years, such as the Italian-run Dolce Vita garment factory in Asmara.

The mainly Eritrean workforce makes designer shirts for Giorgio Armani and Pierre Cardin, as well as uniforms for Italian scouts and jeans for the local market.

Another hope for the Eritrean economy is mining.

Canada’s Nevsun, in joint venture with the government, began producing gold at Bisha mine in 2011. The mine also exploits copper and zinc deposits.

Human rights groups criticised Bisha for using conscripts during the construction phase, but Nevsun and the government deny national service labour is used in commercial mining.

Nevsun says Bisha contributed about $800m (£550m) to the Eritrean economy in its first five years of operation.

A Chinese mining company has recently started operations, and two more mines are expected to come online in the next few years.

But mining, although potentially lucrative, does not generate much employment.

he population is predominantly rural, working the harsh, dry land.

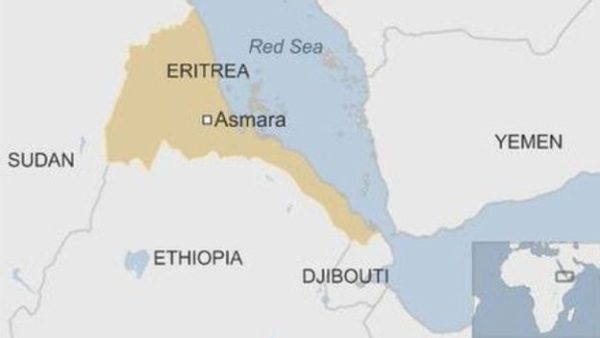

But Eritreans and foreign investors are looking towards the country’s 1,200km (745-mile) Red Sea coastline, with its hundreds of unspoiled islands, rich fish stocks and ports, all of which have significant economic potential.

Whether any of this will be realised will depend on two main factors. Eritrea’s willingness to adopt a more flexible attitude towards its economy, and foreign investors’ readiness to engage with a country that has recently been accused of crimes against humanity and has spent years in international isolation.

Eritrea – key facts:

- Nation of between 3.5 million and 6 million (the figures are disputed) on Red Sea – one of Africa’s poorest countries

- One-party state – no functioning constitution or independent media

- Former Italian colony, later formed loose federation with Ethiopia

- 1962 – Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie dissolved Eritrean parliament, seized Eritrea

- Eritrean separatists – the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front – fought guerrilla war until 1991, when they captured capital Asmara

- Eritrea voted for independence in 1993

- May 1998 border dispute with Ethiopia led to two-year war costing 100,000 lives

- Still no peace settlement – thousands of troops face each other along 1,000km (620-mile) border