PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

The Racist History of Portland, the Whitest City in America

Alana Semuels |

It’s known as a modern-day hub of progressivism, but its past is one of exclusion.

PORTLAND, Ore.— Victor Pierce has worked on the assembly line of a Daimler Trucks North America plant here since 1994. But he says that in recent years he’s experienced things that seem straight out of another time. White co-workers have challenged him to fights, mounted “hangman’s nooses” around the factory, referred to him as “boy” on a daily basis, sabotaged his work station by hiding his tools, carved swastikas in the bathroom, and written the word “nigger” on walls in the factory, according to allegations filed in a complaint to the Multnomah County Circuit Court in February of 2015.

Pierce is one of six African Americans working in the Portland plant whom the lawyer Mark Morrell is representing in a series of lawsuits against Daimler Trucks North America. The cases have been combined and a trial is scheduled for January of 2017.

“They have all complained about being treated poorly because of their race,” Morrell told me. “It’s a sad story—it’s pretty ugly on the floor there.” (Daimler said it could not comment on pending litigation, but spokesman David Giroux said that the company prohibits discrimination and investigates any allegations of harassment.)

All in all, historians and residents say, Oregon has never been particularly welcoming to minorities. Perhaps that’s why there have never been very many. Portland is the whitest big city in America, with a population that is 72.2 percent white and only 6.3 percent African American.

“I think that Portland has, in many ways, perfected neoliberal racism,” Walidah Imarisha, an African American educator and expert on black history in Oregon, told me. Yes, the city is politically progressive, she said, but its government has facilitated the dominance of whites in business, housing, and culture. And white-supremacist sentiment is not uncommon in the state. Imarisha travels around Oregon teaching about black history, and she says neo-Nazis and others spewing sexually explicit comments or death threats frequently protest her events.

Violence is not the only obstacle faced by black people in Oregon. A 2014 report by Portland State University and the Coalition of Communities of Color, a Portland non-profit, shows black families lag far behind whites in the Portland region in employment, health outcomes, and high-school graduation rates. They also lag behind black families nationally. While annual incomes for whites nationally and in Multnomah County, where Portland is located, were around $70,000 in 2009, blacks in Multnomah County made just $34,000, compared to $41,000 for blacks nationally. Almost two-thirds of black single mothers in Multnomah County with kids under five lived in poverty in 2010, compared to half of black single mothers with kids under five nationally. And just 32 percent of African Americans in Multnomah County owned homes in 2010, compared to 60 percent of whites in the county and 45 percent of blacks nationally.

“Oregon has been slow to dismantle overtly racist policies,” the report concluded. As a result, “African Americans in Multnomah County continue to live with the effects of racialized policies, practices, and decision-making.”

Whether this history can be overcome is another matter. Because Oregon, and specifically Portland, its biggest city, are not very diverse, many white people may not even begin to think about, let alone understand, the inequalities. A blog, “Shit White People Say to Black and Brown Folks in PDX,” details how racist Portland residents can be to people of color. “Most of the people who live here in Portland have never had to directly, physically and/or emotionally interact with PoC in their life cycle,” one post begins.

As the city becomes more popular and real-estate prices rise, it is Portland’s tiny African American population that is being displaced to the far-off fringes of the city, leading to even less diversity in the city’s center. There are around 38,000 African Americans in the city in Portland, according to Lisa K. Bates of Portland State University; in recent years, 10,000 of those 38,000 have had to move from the center city to its fringes because of rising prices. The gentrification of the historically black neighborhood in central Portland, Albina, has led to conflicts between white Portlanders and long-time black residents over things like widening bicycle lanes and the construction of a new Trader Joe’s. And the spate of alleged incidents at Daimler Trucks is evidence of tensions that are far less subtle.

“Portland’s tactic when it comes to race up until now, has been to ignore it,” said Zev Nicholson, an African American resident who was, until recently, the Organizing Director of the Urban League of Portland. But can it continue to do so?

* * *

From its very beginning, Oregon was an inhospitable place for black people. In 1844, the provisional government of the territory passed a law banning slavery, and at the same time required any African American in Oregon leave the territory. Any black person remaining would be flogged publicly every six months until he left. Five years later, another law was passed that forbade free African Americans from entering into Oregon, according to the Communities of Color report.

In 1857, Oregon adopted a state constitution that banned black people from coming to the state, residing in the state, or holding property in the state. During this time, any white male settler could receive 650 acres of land and another 650 if he was married. This, of course, was land taken from native people who had been living here for centuries.

This early history proves, to Imarisha, that “the founding idea of the state was as a racist white utopia. The idea was to come to Oregon territory and build the perfect white society you dreamed of.” (Matt Novak detailed Oregon’s heritage as a white utopia in this 2015 Gizmodo essay.)

With the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, Oregon’s laws preventing black people from living in the state and owning property were superseded by national law. But Oregon itself didn’t ratify the 14th Amendment—the Equal Protection Clause—until 1973. (Or, more exactly, the state ratified the amendment in 1866, rescinded its ratification in 1868, and then finally ratified it for good in 1973.) It didn’t ratify the 15th Amendment, which gave black people the right to vote, until 1959, making it one of only six states that refused to ratify that amendment when it passed.

This history resulted in a very white state. Technically, after 1868, black people could come to Oregon. But the black-exclusion laws had sent a very clear message nationwide, says Darrell Millner, a professor of black studies at Portland State University. “What those exclusion laws did was broadcast very broadly and loudly was that Oregon wasn’t a place where blacks would be welcome or comfortable,” he told me. By 1890, there were slightly more than 1,000 black people in the whole state of Oregon. By 1920, there were about 2,000.

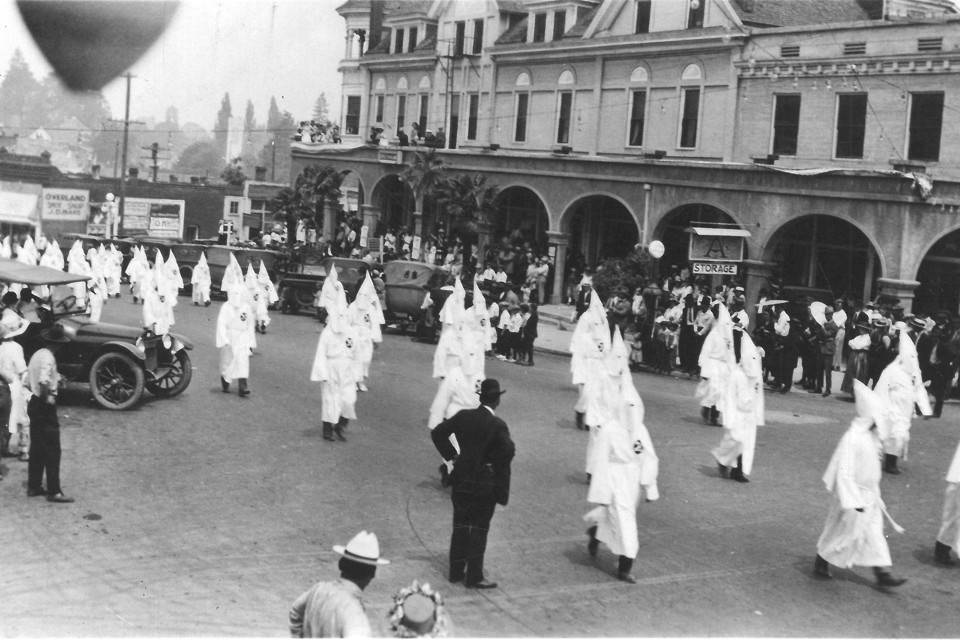

The rise of the Ku Klux Klan made Oregon even more inhospitable for black people. The state had the highest per capita Klan membership in the country, according to Imarisha. Democrat Walter M. Pierce was elected to the governorship of the state in 1922 with the vocal support of the Klan, and photos in the local paper show the Portland chief of police, sheriff, district attorney, U.S. attorney, and mayor posing with Klansmen, accompanied by an article saying the men were taking advice from the Klan. Some of the laws passed during that time included literacy tests for anyone who wanted to vote in the state and compulsory public school for Oregonians, a measure targeted at Catholics.

Dismantling Vanport proved unnecessary. In May of 1948, the Columbia River flooded, wiping out Vanport in a single day. Residents had been assured that the dikes protecting the housing were safe, and some lost everything in the flood. At least 15 residents died, though some locals formulated a theory that the housing authority had quietly disposed of hundreds more bodies to cover up its slow response. The 18,500 residents of Vanport—6,300 of whom were black—had to find somewhere else to live.

For black residents, the only choice, if they wanted to stay in Portland, was a neighborhood called Albina that had emerged as a popular place to live for the black porters who worked in nearby Union Station. It was the only place black people were allowed to buy homes, after, in 1919, the Realty Board of Portland had approved a Code of Ethics forbidding realtors and bankers from selling or giving loans to minorities for properties located in white neighborhoods.

As black people moved into Albina, whites moved out; by the end of the 1950s, there were 23,000 fewer white residents and 7,000 more black residents than there had been at the beginning of the decade.

The neighborhood of Albina began to be the center of black life in Portland. But for outsiders, it was something else: a blighted slum in need of repair.

* * *

Today, North Williams Avenue, which cuts through the heart of what was once Albina, is emblematic of the “new” Portland. Fancy condos with balconies line the street, next to juice stores and hipster bars with shuffleboard courts. Ed Washington remembers when this was a majority black neighborhood more than a half a century ago, when his parents moved their family to Portland during the war in order to get jobs in the shipyard. He says every house on his street, save one, was owned by black families.

“All these people on the streets, they used to be black people,” he told me, gesturing at a couple with sleeve tattoos, white people pushing baby strollers up the street.

Since the postwar population boom, Albina has been the target of a decades of “renewal” and redevelopment plans, like many black neighborhoods across the country.

In 1956, voters approved the construction of an arena in the area, which destroyed 476 homes, half of them inhabited by black people, according to “Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940-2000,” a paper by the Portland State scholar Karen J. Gibson. This forced many people to move from what was considered “lower Albina” to “upper Albina.” But upper Albina was soon targeted for development, too, first when the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 provided funds for Portland to build Interstate 5 and Highway 99. Then a local hospital expansion was approved, clearing 76 acres, including 300 African American-owned homes and businesses and many shops at the junction of North Williams Avenue and Russell Street, the black “Main Street.”

The urban-renewal efforts made it difficult for black residents to maintain a close-knit community; the institutions that they frequented kept getting displaced. In Portland, according to Gibson, a generation of black people had grown up hearing about the “wicked white people who took away their neighborhoods.” In the meantime, displaced African Americans couldn’t acquire new property or land. Redlining, the process of denying loans to people who lived in certain areas, flourished in Portland in the 1970s and 1980s. An investigation by The Oregonian published in 1990 revealed that all the banks in Portland together had made just 10 mortgage loans in a four-census-tract area in the heart of Albina in the course of a year. That was one-tenth the average number of loans in similarly-sized census tracts in the rest of the city. The lack of available capital gave way to scams: A predatory lending institution called Dominion Capital, The Oregonian alleged, also “sold” dilapidated homes to buyers in Albina, though the text of the contracts revealed that Dominion actually kept ownership of the properties, and most of the contracts were structured as balloon mortgages that allowed Dominion to evict buyers shortly after they’d moved in. Other lenders simply refused to give loans on properties worth less than $40,000. (The state’s attorney general sued Dominion’s owners after The Oregonian‘s story ran; the AP reported that the parties reached a settlement in 1993 in which Dominion’s owners agreed to pay fines and to limit their business activity in the state. The company filed for bankruptcy a few days after the state lawsuit was filed; U.S. bankruptcy court handed control of the company to a trustee in 1991.)

The inability of blacks to get mortgages to buy homes in Albina led, once again, to the further decimation of the black community, Gibson argues. Homes were abandoned, and residents couldn’t get mortgages to buy them and fix them up. As more and more houses fell into decay, values plummeted, and those who could left the neighborhood. By the 1980s, the value of homes in Albina reached 58 percent of the city’s median.

“In Portland, there is evidence supporting the notion that housing market actors helped sections of the Albina District reach an advanced stage of decay, making the area ripe for reinvestment,” she writes.

By 1988, Albina was a neighborhood known for its housing abandonment, crack-cocaine activity, and gang warfare. Absentee landlordism was rampant, with just 44 percent of homes in the neighborhood owner-occupied.

It was then, when real estate prices were at rock bottom, that white people moved in and started buying up homes and businesses, kicking off a process that would make Albina one of the more valuable neighborhoods in Portland. The city finally began to invest in Albina then, chasing out absentee landlords and working to redevelop abandoned and foreclosed homes.

Much of Albina’s African American population would not benefit from this process, though. Some could not afford to pay for upkeep and taxes on their homes when values started to rise again; others who rented slowly saw prices reach levels they could not afford. Even those who owned started to leave; by 1999, blacks owned 36 percent fewer homes than they had a decade earlier, while whites owned 43 percent more.

This gave rise to racial tensions once again. Black residents felt they had been shouting for decades for better city policy in Albina, but it wasn’t until white residents moved in that the city started to pay attention.

“We fought like mad to keep crime out of the area,” Gibson quotes one long-time resident, Charles Ford, as saying. “But the newcomers haven’t given us credit for it…We never envisioned the government would come in and mainly assist whites…I didn’t envision that those young people would come in with what I perceived as an attitude. They didn’t come in [saying] ‘We want to be a part of you.’ They came in with this idea, ‘we’re here and we’re in charge’…It’s like the revitalization of racism.”

* * *

Many might think that, as a progressive city known for its hyper-consciousness about its own problems, Portland would be addressing its racial history or at least its current problems with racial inequality and displacement. But Portland only recently became a progressive city, said Millner, the professor, and its past still dominates some parts of government and society.

Until the 1980s, “Portland was firmly in the hands of the status quo—the old, conservative, scratch-my-back, old-boys white network,” he said. The city had a series of police shootings of black men in the 1970s, and in the 1980s, the police department was investigated after officers ran over possums and then put the dead animals in front of black-owned restaurants.

Yet as the city became more progressive and “weird,” full of artists and techies and bikers, it did not have a conversation about its racist past. It still tends not to, even as gentrification and displacement continue in Albina and other neighborhoods.

“If you were living here and you decided you wanted to have a conversation about race, you’d get the shock of your life,” Ed Washington, the longtime Portland resident, told me. “Because people in Oregon just don’t like to talk about it.”

The overt racism of the past has abated, residents say, but it can still be uncomfortable to traverse the city as a minority. Paul Knauls, who is African American, moved to Portland to open a nightclub in the 1960s. He used to face the specter of “whites-only” signs in stores, prohibitions on buying real estate and once, even a bomb threat in his jazz club because of its black patrons. Now, he says he notices racial tensions when he walks into a restaurant full of white people and it goes silent, or when he tries to visit friends who once lived in Albina and who have now been displaced to “the numbers,” which is what Portlanders call the low-income far-off neighborhoods on the outskirts of town.

“Everything is kind of under the carpet,” he said. “The racism is still very, very subtle.”

Ignoring the issue of race can mean that the legacies of Oregon’s racial history aren’t addressed. Nicholson, of the Urban League of Portland, says that when the black community has tried to organize meetings on racial issues, community members haven’t been able to fit into the room because “60 white environmental activists” have showed up, too, hoping to speak about something marginally related.

If the city talked about race, though, it might acknowledge that it’s mostly minorities who get displaced and would put in place mechanisms for addressing gentrification, Imarisha said. Instead, said Bates, the city celebrated when, in the early 2000s, census data showed it had a decline in black-white segregation. The reason? Black people in Albina were being displaced to far-off neighborhoods that had traditionally been white.

One incident captures how residents are failing to hear one another or have any sympathy for one another: In 2014, Trader Joe’s was in negotiations to open a new store in Albina. The Portland Development Commission, the city’s urban-renewal agency, offered the company a steep discount on a patch of land to entice them to seal the deal. But the Portland African American Leadership Forum wrote a letter protesting the development, arguing that the Trader Joe’s was the latest attempt to profit from the displacement of African Americans in the city. By spending money incentivizing Trader Joe’s to locate in the area, the city was creating further gentrification without working to help locals stay in the neighborhood, the group argued. Trader Joe’s pulled out of the plan, and people in Portland and across the country scorned the black community for opposing the retailer.

Imarisha, Bates, and others say that during that incident, critics of the African American community failed to take into account the history of Albina, which saw black families and businesses displaced again and again when whites wanted to move in. That history was an important and ignored part of the story. “People are like, ‘Why do you bring up this history? It’s gone, it’s in the past, it’s dead.” Imarisha said. “While the mechanisms may have changed, if the outcome is the same, then actually has anything changed? Obviously that ideology of a racist white utopia is still very much in effect.”

Talking constructively about race can be hard, especially in a place like Portland where residents have so little exposure to people who look differently than they do. Perhaps as a result, Portland, and indeed Oregon, have failed to come to terms with their ugly past. This isn’t the sole reason for incidents like the alleged racial abuse at Daimler Trucks, or for the threats Imarisha faces when she traverses the state. But it may be part of it.