PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Africa’s healthcare crisis – some novel solutions

Chijioke Mama | 7 March 2017 | New African

Unable to meet public expectations, healthcare systems in Africa might benefit from both native medicine, its derided sister, and the buzzing tech revolution on the continent.

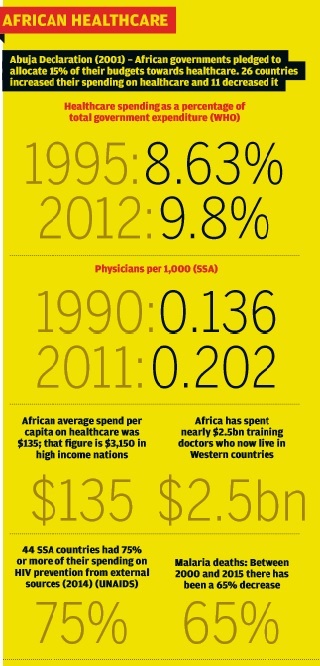

In March 2001, heads of state from across the continent met in Abuja to draft a response to the targets set under the UN’s Millennium Development Goals, adopted by 189 heads of state at the General Assembly in New York seven months earlier. In Abuja, 46 heads of state agreed, among other things, to increase budgetary allocations for health to at least 15% of their annual budgets by 2015. Over the next decade and a half, the Abuja Declaration was tweaked, updated and revisited in a dizzying series of acronym-churning bureaucratic protocols and pledges: “The Africa Health Strategy (2007–2015)”; the “Framework for the implementation of the Ouagadougou Declaration on Primary Health Care and Health Systems in Africa (2010)”; the “Tunis Declaration on Value for Money, Sustainability and Accountability in the Health Sector”.

A decade after its adoption, however, the World Health Organisation was in 2011 forced into observing that “only eight countries are on track with respect to the health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)”. Moreover, said the WHO report, “most countries are achieving less than 50% of the gains that would be required to reach the goals by 2015, with progress on MDG 5 (maternal health) being particularly slow.” As it turned out, only two countries met the MDG deadline targets: South Africa, the continent’s richest country, and Eritrea, which was under sanctions and economically isolated. In 2011, the AU described healthcare in Africa thus: “The African Region has one of the highest disease burdens in the world. The region’s contribution to the global burden of HIV/Aids, TB and malaria is 66%, 26% and 80% respectively … Africa accounted for 46% of under-five deaths, 55% of the maternal deaths, 22% of AIDS-related and 90% of the malaria deaths.”

By 2050, Africa’s population, which currently stands at 1.2 billion people, will have more than doubled to 2.5 billion. Creating a continental healthcare system that meets the needs of its people will be imperative, especially in the light of the growing number of epidemics, such as Ebola, that periodically befall the continent. In 2014, the outbreak of the Ebola virus in West Africa tested the resilience of healthcare systems in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. They were all overpowered within months. The Ebola outbreak highlighted the far-reaching impacts of inadequate healthcare delivery, which lies beyond predispositions to epidemics but also includes severe economic losses and setbacks. According to the World Bank, “an estimated $2.2bn was lost in 2015 in the gross domestic product (GDP) of the three countries”.

Reinventing healthcare in Africa requires well-planned programmes to ensure proper financing; elevating the relevance and utilisation of health research; developing indigenous medical capacity; and modernising traditional medicine as it holds significant but neglected value within the continent. New and transformative lines of action will be required.

Basic healthcare delivery questions

While policymakers delay, Africans who can afford to are seeking quality healthcare services offshore. Sadly, this comes at a huge cost for several struggling economies. According to a recent report by PWC Nigeria: “The Nigerian Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) says that Nigerians spend $1bn annually in medical tourism on a range of care needs. 60% [of this money] is reported to be [concentrated] across the four key specialties of oncology, orthopedics, nephrology and cardiology. This … is a huge (and avoidable) loss for the Nigeria economy”.

The report further states that: “In 2015 the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health’s total expenditure was $5.85bn. Thus, the cost of medical tourism is nearly 20% of the total expenditure including: salaries of all public nurses and other healthcare workers; care programmes like malaria, HIV/Aids, mother and child care; and the operating costs of facilities nationwide.”

This scenario is not unfamiliar to Africans across the continent, especially those in Kenya, South Africa, Zimbabwe and elsewhere, where doctors have resorted to strike action to force their governments to radically improve healthcare and pay them a living wage in a timely manner.

The average African has little or no health insurance coverage. Caregivers in Nigeria, for example, observe that the country’s national health insurance scheme is grossly inadequate. Its limited usefulness and scope depicts the overall perilous state of the healthcare system. A WHO study on healthcare expenditure in African countries stated: “The average total health expenditure in African countries stood at $135 per capita in 2010, which is only a small fraction of the $3,150 spent on health in an average high-income country.” In Botswana, adjudged to have one of the best healthcare systems in Africa and a population of 2.3 million, healthcare expenditure per capita in 2014 was $385. Compare this to Cyprus at $1,819 and Denmark at $6,463. In contrast, Burundi’s stood at $22, Chad’s $37 and the DRC’s $19.

In 22 of the 45 African countries studied by WHO, the level of funding for health is below the minimum level of $44 per capita recommended for 2009 by the High Level Task Force on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems.

At a federal tertiary healthcare centre in South-Eastern Nigeria, government workers who are under the insurance scheme believe they are very gullible. The amount and quality of medication available for this class of so-called “covered” citizens is so narrow that one senior staffer says ”we believe this programme is a sham”.

Dr Stephen Eze is a senior registrar at a hospital in Owerri, Nigeria. He says: “The functionality of this national insurance scheme tells you that the entire system is a joke. Nigeria’s total budgetary allocation to the healthcare system is abysmally poor. A country as big as ours is sadly among the five or 10 countries in the world with the lowest budgetary allocation to healthcare. What then do you expect to get at its hospitals?” He laments that the inadequate amount allocated to the health sector also gets smaller every passing year, pointing to a systemic and sustained negligence for the health sector.

Eze intends to leave Nigeria once he is done with his studies in gynaecology. “Many of us doctors are already gone. I don’t see why I should stay back here.”

Three decades after much of sub-Saharan Africa’s healthcare systems were devastated by the withdrawal of government support, a standard ingredient of Structural Adjustment austerity, healthcare continues to be plagued by a chronic brain-drain. Qualified healthcare professionals in Africa are leaving in search of more functional systems and climes. According to the WHO: “A shortage of human resources in the health sector is one of the biggest challenges facing the Rwandan government. In order to fill the gaps, the government has invested significant resources in pre-service training institutes.”

The British Medical Journal notes that, “African countries have spent about $2.6bn training doctors who are now living in Western countries.” A staggering 25% to 50% of African-born doctors are working overseas. Zimbabwe and South Africa have the most doctors living abroad, while Australia, Canada, the UK and the US are the main beneficiaries. In Enugu state, Eastern Nigeria, Dr O. C. Amu, a urologist in private practice and a specialist in laser surgery, can barely meet the demand for his services. One of only three surgeons in Nigeria trained in laser surgery, he has significantly reduced the huge Nigerian patient-traffic to India (for prostate surgery, especially). Trained in India himself, he frequently laments the paucity of requisite skills and opportunities for advanced capacity building in the Nigerian healthcare system.

The continuing departure of qualified medical personnel from Africa often leaves a lean pool of less qualified healthcare givers. This in turn provides further motivation for wealthy patients to seek treatments abroad, thereby triggering a vicious circle of escalating expenses on medical tourism bills and lost opportunities at home, especially for the poor who, with no access to professional medical staff, often resort to superstition, witchcraft and dubious herbal treatments.

Leveraging traditional medicine

The use of herbal remedies in the African healthcare system is quite widespread. However, can Africa turn to traditional medicine without the usual bias from modern medicine and healthcare policy makers? Is traditional medicine simply incompatible with modern medicine and of limited relevance to the healthcare delivery discourse? A rich repository of indigenous knowledge, traditional medicine, despite its proven usefulness, is still treated with much disdain, especially by the medical community. All the same, could it provide a pathway to Africa’s healthcare crisis?

It is instructive that the multi-billion dollar business of pharmacognosy – defined as the branch of knowledge concerned with medicinal drugs obtained from plants or other natural sources – undoubtedly feeds off traditional medical knowledge in the Southern hemisphere. And while officialdom and the medical practitioners in Africa continue to shun it, rarely is a moment spent weighing up the massive import costs involved in providing the drugs that are the direct result of the bio-piracy that sustains the Western drug research, and a disjointed African knowledge industry that sees no use in researching the continent’s indigenous herbal treatments.

The quest to revamp healthcare in Africa might well benefit from recent technological improvements.

But things are changing slowly. In Kenya, the University of Nairobi reportedly collected data from an herbal care centre in Nakuru for five years that supports the efficacy of herbal medicine. Professor Julius Mwangi, a professor of pharmacognosy at the University of Nairobi, cited the case of a 70-year-old Kenyan who had prostate cancer and could neither take chemotherapy nor radiotherapy due to his age, and was thus declared unhelpable by care providers at a hospital. When he resorted to being treated with Prunus Africana leaves, his enlarged prostate (not the cancer) was healed.

Africa’s quest to excel in medical research and to champion local drug manufacturing will obviously require a planned expansion of the scope and relevance of herbal medicine, as well as the establishment of a direct channel for knowledge sharing and application in modern medicine. We have to begin looking at the continent’s health problems and solutions from broader perspectives. How can efforts be synchronised in a pan-African model? How can regional progress and lessons learnt in one region be leveraged in other regions? The quest to revamp healthcare in Africa might well benefit from recent technological improvements in the region. Expanding broadband access and smartphone penetration also means that diagnosis and treatment can be delivered remotely while cross- border access to expertise is also made possible. In addition, phone-based solutions can help deliver health insurance schemes to remote locations.

What is needed is a clearly defined pathway towards the greater use of technology in healthcare. Optimising this emerging technological potential will require the establishment of closer ties between telecoms, financial services and healthcare. Interestingly, these possibilities are already beginning to be put to use across several markets. They now need to be scaled – and scaling them will require more effort and closer coordination across borders.