PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

A Marriage Arranged in Heaven?

Didrik Schanche

The relationship between Sudan and China is widely believed to be a marriage anointed in oil: China needs it and Sudan has it, and the two have been in business for years. But the Sudanese say their bond with China runs deeper than any oil well and goes back more than 100 years — to a man who proved the adage “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

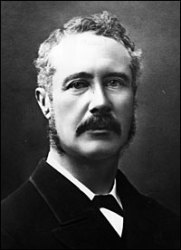

Maj. Gen. Charles Gordon was known as “Chinese” Gordon to his fans — none of whom were even a little Chinese. In the 1860s, Gordon was a star in the firmament of the British armed forces — the go-to guy who made his way to China to help secure Britain’s trading rights there. “Charles Gordon spent some years in China as a British representative during this Imperialistic era,” says Maymouna Mirghani Hamza, who teaches history at Nileen University in Khartoum. Gordon is well known in Sudan, where he headed after making a name for himself among the Chinese. Hamza says Gordon went to great lengths to force British influence in China — apparently at great expense to the Chinese people. “Maybe he did it in excess,” Hamza says.

Fighting For Independence: In the 1860s, then Capt. Gordon — all 5-foot-5-inches of him — helped promote Britain’s interests in China at a time when Britain was itching to sell opium there. Imperial China had outlawed the opium trade, but the Opium Wars humbled the emperor and won lavish trading privileges for Britain and other Western powers. It was a humiliating era for the Chinese, made all the more bitter on the day that Gordon personally oversaw the burning of the emperor’s summer place. Gordon later fought in one of history’s bloodiest rebellions, in which tens of millions of Chinese died.

“He troubled the Chinese very much. And so they were watching what happened to him and his fate. And his fate was here, in the Sudan,” says El Said Ahmed Abdulrahman Al Mahdi, the grandson of the man who later received Gordon’s head on a stick. The elder Mahdi, a bona fide hero in Sudan, was a self-proclaimed descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, and he raised an Islamist anti-colonial army.

He and Gordon, a former governor of the Sudan, reportedly held one another in high esteem. But on Jan. 26, 1885, the Mahdists ran their swords through Gordon on the steps of a palace that he’d had built in Khartoum — and then they cut off his head. The Mahdi army was fighting for Sudan’s independence from all foreign influence. “For three days, the city was at their mercy,” Maymouna Hamza says. “Many people were also killed — Egyptians, Turks, Greeks.” It remains Sudan’s most astounding military victory. News of Gordon’s death raced across Africa like a brush fire in a high wind. Read more

A Story with No Ending: The Mahdi did not live long enough to see the British exact revenge, but at his grandson’s opulent home, there is a portrait of the Mahdi in a white turban, his serious face in three-quarter light, black eyes staring quietly into the middle distance. He has a nose so regal, it could be minted on a coin. His grandson, Abdulrahman, says the Mahdi’s achievement cannot be underestimated. It was the first major defeat of Britain’s colonial forces since the Yankees handed them their hats in the New World.

“The Mahdist movement awakened the peoples who have been colonized and governed by the Europeans and so on,” Abdulrahman says. “It affected the entire Arab world. All the Eastern World. People from China heard. The Chinese, in fact, know very much about the Mahdist movement.” Today, Chinese visitors to Khartoum want to see exactly where Gordon fell, says Ali Abdullah Ali, an economist in downtown Khartoum who has written a book on Sudanese-Chinese relations. Ali, like nearly everyone else here, says the story begins on the day Gordon expired, and so far, it has no ending.

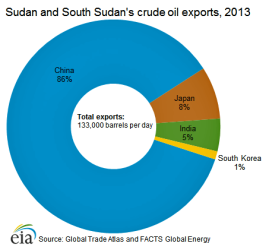

“The Chinese feel we have executed a vendetta for them, you see,” Ali says. “We have revenged for the Chinese, you know, by killing Gordon.” Today, China is Sudan’s No. 1 trading partner, but Gordon didn’t seal that deal — oil did. The Bank of Sudan estimates that the country sells well more than 80 percent of its crude to Beijing. But what gives the relationship flair is the tale of the Mahdi and old Chinese Gordon.

It is widely believed that the Mahdi had wanted Gordon captured alive. Historians say he had plans to convert the general to Islam, or to trade him to Britain in a prisoner exchange. But perhaps even in defeat Gordon would have preferred to remain in Sudan. In his writings, Gordon said he would “sooner follow the Mahdi than go out to dinner every night in London.” That may be why the locals call him Gordon of Khartoum.

As an economic giant with huge investments in Sudan’s oil industry, China could use its friendly influence to sway the government in Khartoum on a variety of issues. But many Sudanese say China’s hand in their affairs is so soft it is almost imperceptible. Ghazi Suleiman, a lawyer and economist in Khartoum, talks about China like a lover, describing economic investment in terms of kisses.

“If someone is exchanging with you kisses,” Suleiman says, “you don’t like him?” In the inferno of summer in Khartoum, Suleiman appears to be a lion in winter. In his office, a fan purrs. He wears a crisp, white suit to match a full head of soft, white curls. He also wears the smile of a single man half his age. Suleiman says China became Sudan’s most important trading partner, when the West turned away. “Chinese are exchanging with us kisses and the Americans are keeping their face away from us. It’s very simple,” he says.

But the story of the relationship between Sudan and China is hardly simple at all. It is a story of a long courtship, complete with rival attractions and expensive gifts.

Following the Money: The Khartoum Stock Exchange occupies a large, airy room with tile floors, a tiny bullpen and a few laptops. Young men in suits and women in head scarves are chatting each other up, waiting for a rally to start. This is “The Little Stock Exchange That Could” — there are only 53 companies listed, and they trade for exactly one hour each day from Sunday to Thursday.

One hour is apparently more than enough, since the companies on the Khartoum exchange do not actually reflect where Sudan’s real money comes from. This economy runs on foreign investment in oil. Japan, Malaysia and India buy a lot of Sudan’s oil, but the Chinese have cornered the market. Economist Ali Abdalla Ali, a chief consultant to the exchange, says the Chinese have already invested billions of dollars. “We’re satisfying about 7 percent of the requirement of China,” Ali says. “Seven percent. And the investment in oil until 2006 was about $9 billion. Only in oil. People are grateful to [the Chinese] because they did this. There are some hitches here and there, you know. But generally, they do for us what other countries would not dare to do.”

“China Was Ready”: Ali, who has written a history of relations between Sudan and China, writes that the relationship heated up in the 1970s, when Chairman Mao Zedong sent aid to Sudan in the form of doctors, engineers, construction workers and interest-free loans. At that time, the Chinese had neither the technology nor the inclination to drill for oil in Sudan. But the Americans did, and Chevron explored the fields until a north-south civil war threatened the company’s investment and it pulled out. Shortly thereafter, Khartoum backed Iraqi President Saddam Hussein in the Gulf War and U.S. sanctions began. When the West pulled out, Ali says, China was ready.

“China became an elephant because of the stupidity and narrow-mindedness of other elephants,” Ali says, referring to the U.S. and Europe. He and others in Khartoum can be very critical of foreign powers, including China. Ali resents the ancillary businesses the Chinese have set up — like hotels, travel agencies and grocery stores — to serve their oil workers in the country. He says the Chinese are taking jobs away from Sudanese who badly need them. “The Chinese now are different from the Chinese of the ’70s,” Ali says. “They are more businesslike. They are really tough businessmen.”

The Darfur Factor: While economic reforms have revolutionized China into a major world power, Sudan’s growth has been hampered by years of civil war, agricultural decline, military coups and spats with the West. And then, of course, there is Darfur. “Actually, we have been talking to the government of Sudan,” says Liu Guijin, China’s envoy to Darfur, speaking last year at peace talks in Libya. “We have maintained a very close contact and consultations with the government of Sudan. Me, myself, when I was nominated the special representative to Darfur, I went to Darfur myself,” Liu says. At the United Nations, China has abstained from voting on most measures designed to entice or force Sudan to protect human rights there. “Of course, we are against the idea of using sanctions to solve the problem,” Liu says, “because there is only one way to solve the problem in Darfur, and that’s through dialogue, consultation.”

With the exception of China’s support for peacekeepers in Darfur, Safwat Fanous, who teaches political science at Khartoum University and is in Parliament as a member of the ruling National Congress Party, has seen no effort by China to help resolve the region’s underlying issues. “Usually in Sudan there are very few secrets,” Fanous says. “If China was playing a mediator role, or putting [on] pressure, we should have seen the results of it.” What is even more curious, Fanous says, is that China has kept such a low profile during recent fighting in Sudan’s Abeyei region between government forces and the army of semi-autonomous [but now independent] South[ern] Sudan. The two sides are fighting over control of the nation’s oil supply. “China has been silent. Completely silent,” Fanous says, noting it has “a lot at stake. So you really wonder how the Chinese are just watching these partners fighting each other, which affects their own investment.”

Agitating For A Democracy: On a purely ideological level, Fanous wonders whether there is any communist ideology left in the People’s Republic of China. “The Sudanese Communist Party is defending the poor people of Sudan in rural areas and urban areas. But the Chinese investment in Sudan has nothing to do with poor people. The Sudanese Communist Party — it has to be embarrassed,” he says. The headquarters of the Communist Party of Sudan are on a quiet residential street in Khartoum. The sign out front is pink, like the bougainvillea flowing over the fence. But Sudan’s communists are not exactly carrying around copies of the Little Red Book, either. Lawmaker Suleiman Hamid El Had says the Sudanese are less concerned with ideology and more interested in survival: “Some people in the Sudan — they eat only one meal a day. Millions of people. It’s very difficult.”

Nearly all of Sudan’s main political parties appear to be agitating for the basic trappings of a democracy, including national elections scheduled for sometime next year. The country has not had multi-party elections in a generation, since well before the military coup that brought the ruling National Congress Party to power. People in Sudan say they want to control their own destiny. “You don’t know how much we can love you, provided you don’t try to tell us what to do,” economist Ali Abdalla Ali says as a warning to the outside world. “You cannot impose your culture on me. But if you respect my culture and if you try to be good to me and really think in terms of the human side of me, we’ll be ready to stand on your side, you know.” China and Sudan may be trading kisses, but the Sudanese would prefer the relationship go no further.

Didrik Schanche is deputy senior supervising editor on NPR’s award-winning International Desk. She also is NPR’s Africa and Latin America editor. A journalist since 1981, Schanche was East Africa Correspondent for the Associated  Press for seven years, producing news stories and features from Sudan and Ethiopia in the north, to Zimbabwe and Zambia in the south. Much of the news in the region then, as now, concerned ethnic conflicts, civil war, drought, hunger, AIDS, and wildlife. After several years as assistant foreign editor at The Washington Times, Schanche made the jump from print reporting to radio in 2001 and came to NPR.

Press for seven years, producing news stories and features from Sudan and Ethiopia in the north, to Zimbabwe and Zambia in the south. Much of the news in the region then, as now, concerned ethnic conflicts, civil war, drought, hunger, AIDS, and wildlife. After several years as assistant foreign editor at The Washington Times, Schanche made the jump from print reporting to radio in 2001 and came to NPR.

Note; This article was written before South Sudan became and independent country in 2011. (AHN editor)