PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

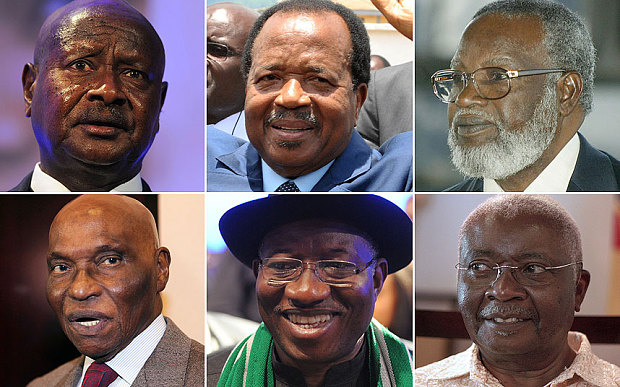

African presidents’ dilemma: Should I stay or should I go?

Burundi’s situation is just the latest example of the chaos caused by presidents wanting to change the constitution and cling on to power. Here we look at some of those who hung on and those who surprised everyone by stepping down

African presidents bending the constitution to their own purposes is nothing new. Sam Nujoma amended Namibia’s constitution in 1999 to allow him a third term as president – he finally ceded power in 2004. Zambia’s Frederick Chiluba and Malawi’s Bakili Muluzi, however, failed to achieve the same amid domestic criticism. There was also speculation that former South African President Thabo Mbeki aspired to a third term as state president with his unsuccessful bid for a third term as president of the ruling African National Congress.

And in Burkina Faso in November 2014, Blaise Compaore was forced to resign after his plans to extend his 27-year rule were met with uproar.

Here is a look at some of the current African leaders who have a tricky relationship with their constitution – those who have succeeded in changing it, those who have failed, and those who are worrying likely to try.

CLINGING ON

Uganda – 2005

Yoweri Museveni of Uganda set the precedent for the current crop of rulers. Shortly after taking power in 1986 he wrote that: “the problem of Africa in general, and Uganda in particular, is not the people but leaders who want to overstay in power.” In an infamous U-turn in 2005, he secured a change to the constitution allowing himself a third term. He is now, at the age of 71, serving a fourth.

Cameroon – 2008

The ruler of Cameroon is the fourth longest-serving president on the continent: only Equatorial Guinea, Angola and Zimbabwe have had to endure their leaders for more time. And although the rulers of Angola and Equatorial Guinea have introduced term limits – which, conveniently for their ageing leaders, are unlikely to affect their own rule – of the four longest-serving leaders, only Paul Biya of Cameroon has successfully overturned the constutition. A two-term limit in the 1996 constitution should have prevented him from running again, but in 2008 he revised the constitution to eliminate presidential term limits. Mr Biya, who came to power in 1982, is thought by most to be hoping to run again in 2018 – if the 82-year-old’s health holds up.

Burundi – 2015

Pierre Nkurunziza was supposed to be the answer to Burundi’s problem of decades of disastrous leadership. A former university lecturer, he became Burundi’s “Minister for Good Governance” and was elected president in 2005. His country had been wracked by civil war and unrest since independence from Belgium in 1962. In 1972 sectarian violence between Hutus and Tutsis saw up to 210,000 people killed, then in 1993 the first Hutu president, Melchior Ndadaye, was assassinated – triggering the loss of a further 25,000 lives through tribal warfare. For the next ten years peace talks continued, with the mediation of Nelson Mandela. And Mr Nkurunziza’s election was supposed to cement the ceasefire, and mark a new era of calm under the 2000 Arusha peace agreement. Initially it worked.

But in April Mr Nkurunziza said he was going to run for a third term – contravening the Arusha agreement, which specifically states that no president can be elected three times. Mr Nkurunziza’s argument was that he had not been actually elected the first time – he said he was elected by parliament, so it didn’t count. In the ensuing violence, 300,000 people fled to neighbouring Rwanda and Tanzania, and generals attempted a coup – which quickly failed. Elections are due on June 26, although they may well be postponed. Mr Nkurunziza is still vowing to run.

DEPARTING WITH DIGNITY

Senegal – 2012

The 2012 presidential election in Senegal was the most controversial, hotly contested and violent in Senegal’s democratic history. The incumbent, 85-year-old Abdoulaye Wade, proposed constitutional changes that would have ensured his success in the next elections by reducing the number of votes needed to win an election. Mr Wade brought in two-term limits, but then said that the rule did not apply to him because his first term begun before the law was passed.

Citizens took to the streets en masse to say enough is enough, with riots in the capital shocking Senegal – the only country in West Africa never to have had a coup. Mr Wade eventually backed down and withdrew the amendment, but he continued his controversial run for a third term.

To the surprise of many, he did not rig the polls and was defeated, and conceded after a second round runoff election. But now Mr Wade has said he will remain as head of his party for the 2017 elections “until a new and promising leader is found”.

Mozambique – 2014

Prior to the October 2014 elections, Mozambique was in turmoil. The president, Armando Guebuza, remained popular, and had no obvious successor. His party, Frelimo, had ruled Mozambique since independence from Portugal in 1975 – first as a one-party state, then through elections. And as Mr Gyebuza was reaching the end of his second term in office, it was unclear what would happen next – Mozambique’s constitution dictated he must step down. Many expected him to claim that “the will of the people” was forcing him to abandon term limits. But to the surprise of many, a successor was found in Filipe Nyusi – a relative unknown. Mr Guebuza, 72, stepped aside, and has recently declared that he will not return to politics.

Nigeria – 2015

The concession of defeat by the Nigerian president, Goodluck Jonathan, after elections in March marked the first time in the nation’s history that an incumbent leader has been ousted at the ballot box. Nigeria’s Constitution limits presidents to two four-year terms. Mr Jonathan ascended to the presidency in 2010 upon the death of incumbent Umaru Yar’Adua, and then won the regularly scheduled election in 2011. Legal challenges to his eligibility to run again in 2015 were overturned by the high court – which meant that he had no need to implement some of his suggestions, such as changing the constitution to allow one longer term.

In a closely-fought election, he was defeated, in a pleasant surprise, did not contest the result. He handed over to Muhammadu Buhari, in the first peaceful transition since the end of military rule in 1999. On May 29, Mr Jonathan will hand [handed] over power to Mr Buhari.

ONES TO WATCH

DRC – 2016

Joseph Kabila, 43, a former taxi driver, rose to power in 2001 after his father, Laurent, was assassinated. He won a second five-year mandate at disputed elections in 2011, and is constitutionally barred from seeking a third term in 2016. In January tentative attempts to overturn the term limit were met with riots, and international NGOs have urged Mr Kabila to commit publicly to standing down next year.

His vast, mineral-rich country has endured the worst conflict since the Second World War – 5.4 million people have been killed since 1998. And Mr Kabila’s peaceful relinquishing of power is seen as absolutely essential in preventing another upsurge of violence, and ensuring economic development. The IMF forecasts its economy will be one of the fastest-growing in the world this year, expanding by 10.5 per cent – mainly driven by mining, which makes up 15 per cent of GDP.

Congo-Brazzaville – 2016

In April Denis Sassou N’Guesso, president of Congo-Brazzaville, announced that he too wanted to change the constitution. The current law does not allow the president, one of Africa’s longest serving leaders, to run for another term in next year’s presidential election. President from 1979 to 1992, he was ousted then re-elected in 1997. “I think the current constitution can be improved, which is why we need to let the debate happen,” he said.

Benin – 2016

Benin President Thomas Boni Yayi promised voters and world leaders including Barack Obama he would step down when his second term expires next year – but doubts over his pledge remain. His plans to reform Benin’s constitution – which would introduce a national electoral commission and state auditor to fight corruption and ensure democratic elections – have fed the suspicions about the president’s real intentions.

Rwanda – 2017

Paul Kagame has effectively ruled Rwanda since the genocide of 1994, which saw 800,000 people massacred in 100 days. He was initially vice president, but accepted as de facto ruler; in 2000 he was elected president. The 57-year-old has served the two seven-year terms permitted by the constitution, but has remained worryingly ambiguous about his intentions ahead of 2017 elections. “I belong to the group that doesn’t support change of the constitution,” he said in April. “But in a democratic society, debates are allowed and they are healthy. “I’m open to going or not going depending on the interest and future of this country.”