PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

Amama Mbabazi: ‘If I didn’t fear Idi Amin then, I won’t have fear now,’ says Uganda’s former PM who has a history of bringing down tyrannical rulers

“I could be arrested,” says Amama Mbabazi. “I would not be surprised – but I’ve been engaged in too many struggles against regimes to be fearful.”

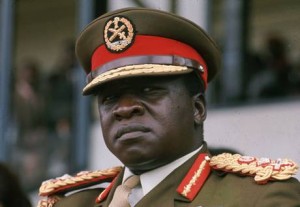

As a revolutionary who helped depose one of Africa’s most brutal dictators in 1979, and another repressive tyrant six years later, Mr Mbabazi – himself a former Prime Minister of Uganda – has a history of bringing down rulers of the East African nation. “If I didn’t fear Idi Amin then, I won’t have fear now,” he says.

Now Mr Mbabazi has a fresh target in his sights: Yoweri Museveni, Uganda’s President for the past 29 years, a long-time political ally. He has triggered an angry and potentially dangerous row within Uganda’s ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) by announcing plans to oust his former friend, become leader of the NRM at its convention in October and its candidate for president in next year’s election.

His move is a gamble, and not just politically. The ruling party is so stitched into the fabric of society that after three decades in power the giant political crocodile of the NRM can sink its teeth into any individual who opposes it. Nor is the risk confined to the former Prime Minister, who was sacked by Mr Museveni at the first whiff of mutiny last year; anyone who backs him also faces dangers.

In recent days, “at least 33 of my supporters from all corners of Uganda have been arrested by the police,” Mr Mbabazi said. “They’ve been arrested simply because they’ve expressed the opinion that they support Mbabazi for president. That’s all, they’ve not done anything else.”

Speaking to The Independent, Mr Mbabazi – himself 66, only four years younger than the man he is attempting to displace – insisted he was committed to becoming a transitional president only, vowing swiftly to hand power on to a newer generation of leaders once he has addressed the concerns of millions of young people experiencing crippling job shortages.

“There is a very strong feeling in the population that it is time to change leadership,” he said.

Uganda has the largest percentage of young people under 30 in the world – 78 per cent – according to a 2012 report by the UN Population Fund. And despite consistent GDP growth during the last decade, this has failed to translate into jobs for many of its 37 million strong population. Health care is in a shambolic state while a greater focus on providing quality education is desperately needed – and economic corruption remains a major problem.

“Having put the basics in place we need to go to another level,” Mr Mbabazi said. “The population doesn’t think Museveni is the leader to take us to the level of development that we’d like to pursue.”

The incumbent president, 70, who once said that Africa’s main problem was rulers clinging on to power, has now ruled for almost three decades – an example of Africa’s still obdurate “big man” rulers; relying on extensive patronage networks and the legacy of revolutionary struggle to sustain popular support.

And there are no signs the country’s ageing leader has any intention of ceding power any time soon.

Mr Museveni and the former Prime Minister were comrades in arms during their struggle against the murderous regime of Idi Amin, and then worked together for the liberation of Uganda from his successor, Milton Obote, whose tyrannical rule caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Ugandans.

During the first years of Mr Museveni’s leadership the NRM re-established the Ugandan state, law and security while implementing social campaigns to end the devastating Aids pandemic of the 1980s.

The gradual degrading of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in the north of the country in recent years has brought increased peace and security to one of Africa’s most impoverished regions.

However, the President has infuriated the West by tolerating an ugly crackdown on the country’s fearful gay community, only dropping a 2014 anti-homosexuality bill that included the death penalty for some offences after threats that governments would cancel aid budgets. Meanwhile, he has repeatedly reneged on promises to step down, citing the need first to find a successor with vision who must be “a nationalist, patriotic and pan-African, one that promotes social economic transformation and is democratic”.

Many Ugandan citizens believe that he intends to be President for life.

“He’ll never go! He has so much power that he’d be mad to give it up. It is a shame as we still respect him for what he’s done,” said Daniel, a 55-year-old teacher from Lira, northern Uganda, who asked that his surname not be published.

Earlier this week police attempted to bar Mr Mbabazi from holding meetings to promote his challenge to Mr Museveni, saying the ruling party had not yet nominated a candidate. “Your aspirations are illegal,” warned the country’s inspector general of police, Kale Kayihura.

Although Uganda’s 2005 referendum restored multi-party politics after two decades of one-party rule, the nascent opposition parties lack the support to take on the NRM at the polls and Kizza Besigye, the most popular opposition leader who has lost three times against Mr Museveni, has faced repeated arrest with his own public rallies often broken up by police.

Mr Mbabzi’s view is that Uganda would fare better if the NRM continues in power, so long as it is under his leadership. “We cannot afford the luxury of division,” he said.