PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

ABOUT ‘AFRICAN SOLUTIONS TO AFRICAN PROBLEMS’

Kasaija Phillip Apuuli:

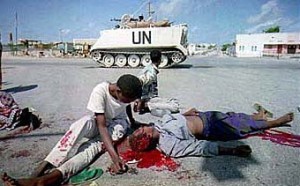

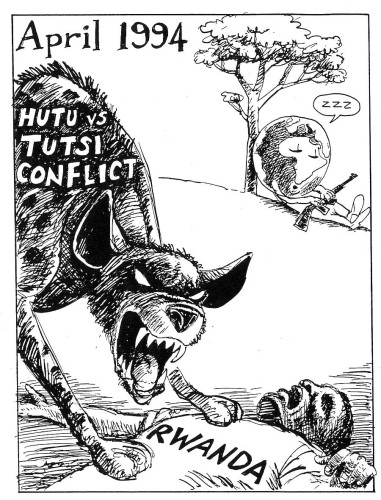

In the aftermath of the failure of the international community in the 1990s to decisively deal, inter alia, with the genocide in Rwanda and state collapse in Somalia, African countries resolved to craft their own solutions to the problems emerging on the continent.

This marked the origin of the notion of African solutions to Africa s problems, which was later to become one of the founding principles of the AU. It should be recalled that the inauguration of the OAU in 1963 represented the institutionalization of pan-African ideals. However, the organization was impotent in its efforts to positively influence national politics, monitor the internal behavior of member states, and prevent human rights violation atrocities.

The OAU Charter contained a provision to defend the sovereignty, territorial integrity and independence of member states which came to be translated into the norm of non-intervention. The transformation of the OAU to the AU was meant to be a policy shift by which the new organization would become an effective mechanism to deal with the numerous problems afflicting the continent. Thus, the notion of noninterference was replaced with that of non-indifference, based on the possibility that a fire engulfing your neighbor’s hut could well spread to your own.

Nevertheless, the crises in Côte d’Ivoire and Libya exposed in the two cases, the hollowness of the AU being an African solution to African problems. This paper argues that marginalization of the organization was self-inflicted because, had it taken a very strong united stance when the crises broke out, it would have created a strong basis from which to preclude the eventual direct intervention of the UN and France in Côte d’Ivoire; and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the UN in Libya. However, from the very beginning, the organization took half-hearted measures in its reaction, which eventually resulted in its being overridden. Moreover, the AU was saddled with problems, including fissures within its ranks, which precluded it from playing a very active and meaningful role in the crises, and caused it to be relegated into a mere bystander to a game being played within its own backyard.

Côte d’Ivoire: On 31 October 2010, Côte d’Ivoire successfully conducted a much delayed and repeatedly extended presidential election. Marking an important step towards ending the protracted political crisis triggered by the civil war that started in September 2002, the election was held in an atmosphere that was generally free of violence. The election also registered a high voter turnout of 80 percent, signifying the strong desire of the public for the crisis to end. The high level of public participation in the election increased the legitimacy of the polls and demonstrated some success of the preparations and campaigning, and most importantly the enthusiasm of the public for a return to normalcy. The polling was conducted in an atmosphere that was largely free of violence, with the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General Choi Young-Jin subsequently informing the UN that no major human rights violation had been recorded during the voting.

Although the electoral timeline envisaged that the electoral commission should announce election results within 72 hours following the closure of polling stations on 3 November 2010, the Independent Electoral Commission (CEI) started to announce preliminary results on 2 November 2010. When the final results of the election were eventually announced by the CEI on 3 November 2010, none of the three main contenders had attained the 50% threshold to win the first round. Of the 14 candidates competing for the top position, the incumbent Laurent Gbagbo ranked first with a total of 38.3 percent of votes, followed by [Alassane] Ouattara with 32.08 percent and Bédié with 25.24 percent. This meant that Gbagbo and Ouattara, being first and second, would go for the second round.

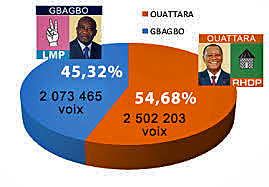

The second round of the 28 November 2010 presidential elections pitted Ouattara, the candidate of the Union of Houphouëtists for Democracy and Peace (RHDP) against Gbagbo, outgoing president and candidate of the Presidential Majority (LMP). Ouattara won the election with 54.1 per cent of the votes, but Gbagbo did not accept the result announced by the CEI and certified by the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI).

He therefore manipulated the Constitutional Council to stay in power. Headed by a Gbagbo associate, the Council cancelled more than 660 000 votes in seven departments favorable to Ouattara and proclaimed Gbagbo the winner with 51.4 per cent of the votes against 45.9 per cent for his opponent. However, this manipulation of the electoral results was so hasty and clumsy that the figures finally issued were wrong since the areas in which elections were cancelled were not sufficient to factually change the overall result of the election. Gbagbo thus embarked on a campaign of terror against Ouattara’s supporters in order to stifle protest, while the latter allied himself with the former rebels of the Forces Nouvelles.

After several months of clashes in Abidjan and elsewhere between the FN forces and army units and militias loyal to Gbagbo, and failed diplomatic mediation by the AU and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Ouattara launched a countrywide military offensive on 28 March 2011. This victorious offensive, which led to Gbagbo s arrest on 11 April 2011, was facilitated by the direct intervention of UN and French Force Licorne helicopters, as authorized by Security Council Resolution 1975 to prevent the use of heavy weapons by the Gbagbo government against the civilian population. After arrest, Gbagbo was transferred to the north of the country where he was held in detention, until his transfer to The Hague into the custody of the International Criminal Court (ICC), to await trial.

Libya: Inspired by the events in Tunisia and Egypt (also called the Arab Spring), in which ordinary people took to the streets to force out the governments there, the people in Eastern Libya began an uprising against the government of Muammar Gaddafi in mid-February 2011. The rebels immediately took control of several towns including Benghazi, the second biggest town in Libya.

During his 42 years of rule, Gaddafi imposed a repressive system of government devoid of any of the institutional features common even to many of the world’s most undemocratic regimes. When he first took over power in a military coup in September 1969, Gaddafi introduced his so-called Third Universal Theory which advanced the idea that people should directly run the activities and exercise the powers of government. The result of this system over the years was the virtual absence of any development of a state bureaucracy or any form of institutionalized governmental structure. In Gaddafi s Libya therefore, there was neither a constitution in the modern sense or any political parties.

The immediate trigger of the crisis were the events in neighboring Tunisia and Egypt where, between January and February 2011, the people forced out Presidents Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak respectively, in public demonstrations and protests. In the case of Libya, the protests began on 15 February in the eastern city of Benghazi where people staged a protest against the government for arresting a human rights campaigner. As in Tunisia and Egypt, opposition groups used social network computer sites such as Facebook to call on people to stage protests.

The lethal and indiscriminate use of force by security forces on un-armed protesters resulted in condemnation by the international community. The protesters established a Transitional National Council (TNC), headed by former Justice Minister Mustafa Mohamed Abud Al Jeleil, to spearhead the struggle against the Gaddafi government.

As the rebellion rolled out west towards Libya’s capital, Tripoli, the Gaddafi government mobilized its forces to confront it. By the end of the month of February 2011, Gaddafi s forces had been able to take back several towns that had been overrun by the rebels and were threatening a bloodbath in Benghazi. In the meantime, the AU s Peace and Security Council (AU PSC) met one week after the rebellion broke out and issued a communiqué spelling out its intention to send a fact-finding mission to Libya.

As the PSC was preparing itself, and in response to the threat from Gaddafi forces to crush the rebellion, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) passed resolution 1973 authorizing the use of force to protect the civilian people. This marked the beginning of western countries intervention in the Libya crisis.

On Sunday, 21 August 2011, rebels launched an offensive to take Tripoli from Gaddafi’s forces. They made rapid progress and by the end of the week had overrun much of the capital although sporadic fighting continued in parts of the city. Whilst Gaddafi went into hiding, he continued making radio broadcasts urging his followers to fight and take back the city. Rebel forces captured the city of Sirte on 20 October 2011 and subsequently news started filtering out that Gaddafi had been killed. When it was confirmed, Gaddafi s death effectively brought to an end the war in Libya.

The AU, conflict resolution and the notion of ‘African solutions to African problems’: Whilst establishing the AU, African leaders recognized the scourge of conflicts in Africa as constituting a major impediment to the socio-economic development of the continent. They also noted that the need to promote peace, security and stability is a prerequisite for the implementation of development and integration agenda. Whilst the AU is guided by the objective of promot[ing] peace, security and stability on the continent, it is also based on the principle of respect for the sanctity of human life.

The AU leaders recognized the failures of the OAU in the area of conflict resolution. Due to the doctrine of non-intervention, the OAU became a silent observer to the atrocities committed by some of its member states. A culture of impunity and indifference was cultivated and became entrenched in the international relations of the African countries. Thus, learning from the lessons of the OAU, when the Africa leadership decided to establish the AU, they adopted a much more interventionist stance in the organization’s legal frameworks and institutions.

Apropos of the legal framework, for example, the Constitutive Act declared that the Union had a right to intervene in a Member State pursuant to a decision of the Assembly in respect of grave circumstances, namely war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity. Also, member states were given a right to request intervention from the Union in order to restore peace and security. Finally, the member states of the Union were enjoined to respect democratic principles, human rights, the rule of law and good governance. These principles were a marked departure from the Charter of the OAU.

With regard to institutions, the AU sought to create robust conflict resolution organs to replace those of the moribund OAU. During the formative process of the AU, the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the OAU meeting in Lusaka, Zambia, in July 2001, adopted Decision 8 on the implementation of the Sirte Declaration (on the establishment of the AU, adopted in 1999), including the incorporation of other Organs.

It was on the basis of this decision and Article 5(2) of the Constitutive Act that the AU PSC replaced the Central Organ of the OAU Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management and Resolution (CPMR), established under the 1993 Cairo Declaration. The Cairo Declaration had signaled Africa s determination to resolve its own problems.

This was the firm indication of the African leadership’s resolve to craft African solutions to African problems. But the OAU s Mechanism for CPMR was not effective at all; as it did not deal, for example, with the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, or the crises in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Moreover, it relied on the goodwill and consent of the state concerned.

The Protocol relating to the Establishment of the PSC was adopted by the inaugural meeting of the Assembly of the Union held in Durban, South Africa, in July 2002 and entered into force on 26 December 2003. Due to the conflicts on the continent, the PSC has been compelled to deal mainly with country-focused issues and thus, when the crises in Côte d’Ivoire and Libya broke out, it was seized of the matters. This was in the spirit of having African solutions to African problems.

The AU and the crises in Côte d’Ivoire and Libya:

Côte d’Ivoire (Efforts by ECOWAS): In the aftermath of the second-round of voting in Côte d’Ivoire, and the failure of incumbent president Gbagbo to cede power to the winner Ouattara, the AU PSC in a press statement on 4 December 2010 expressed its total rejection of any attempt to create a fait accompli to undermine the electoral process and the will of the people.

The PSC declaration came on the same day that ECOWAS issued a statement which condemned any attempt to usurp the popular will of the people of Côte d’Ivoire and appealed to all stakeholders to accept the results declared by the electoral commission. Incidentally, as the AU and ECOWAS were condemning what was happening in Côte d’Ivoire, both Ouattara and Gbagbo were inaugurating themselves as duly elected president of the country.

On 7 December 2010, the ECOWAS Authority of Heads of State and Government met in an extraordinary session and formally recognized Ouattara as President-elect of Côte d’Ivoire representing the freely expressed voice of the Ivorian people. Two days after, the AU PSC endorsed the ECOWAS position and decided to suspend the participation of Côte d’Ivoire in all AU activities until such a time the democratically-elected President assumes state power. Gbagbo ignored the AU and ECOWAS’s calls and declarations to cede power to Ouattara.

Frustrated by the intransigence of Gbagbo, ECOWAS ratcheted up its pressure. At an extraordinary meeting of its authority held at Abuja on the eve of Christmas 2010, the heads of state and government reiterated their position of recognition of Ouattara as the legitimate president of Côte d’Ivoire as non-negotiable and expressed their support for a travel ban, freeze on financial assets and all other forms of targeted sanctions imposed by regional institutions and the international community on the out- going president and his associates…in the event that their message was not heeded.

The Committee of ECOWAS military chiefs met twice in Abuja, Nigeria, on 29 to 30 December 2010, and Bamako, Mali, on 18 to 19 January 2011, to consider options available for forcefully removing Gbagbo if political persuasion failed. Nevertheless, the contemplated military action faced challenges, including the fissures that developed among the ECOWAS countries apropos of the intervention.

There was no strong political will and consensus among the ECOWAS countries for the intervention. Ghana, for example, indicated that it would not contribute troops to an ECOWAS regional force to oust Gbagbo on the ground that its military was engaged in many peacekeeping operations around the world, including Côte d’Ivoire.

ECOWAS’s proposal to remove Gbagbo by force also received lukewarm support from the UN. Under the UN Charter, the UN must authorize any action taken by a regional arrangement or agency apropos of the enforcement measures for the maintenance of international peace and security. With regard to the ECOWAS contemplated military action in Côte d’Ivoire, the UN Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, Alain Le Roy, disclosed that: We are not part of any military operation or option prepared by ECOWAS; it’s purely ECOWAS decision. The UN ambivalence sent wrong signals to the ECOWAS countries which were already preparing to contribute troops to the mission.

Côte d’Ivoire (AU Mediation): As ECOWAS was contemplating military action to remove Gbagbo, the AU was continuing with mediation attempts. On 4 December 2010, the Chairperson of the AU Commission, Jean Ping, requested former South African President Thabo Mbeki to travel to Abidjan to mediate a peaceful outcome of the dispute. After meeting the disputants and the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General Choi, Mbeki failed in his mission and left the country after making a generic call for peace and democracy to prevail.

The AU’s most serious attempt (or was it?) to end the Côte d’Ivoire crisis after the failure of the Mbeki mission was its appointment of Kenya s Prime Minister Raila Odinga as mediator in the conflict. Odinga was asked by Ping to lead the monitoring of the situation in Côte d’Ivoire and bolster the efforts being undertaken to end the turmoil.

The choice of Odinga as mediator was baffling because, at the beginning of the dispute he had declared that Gbagbo must be forced out, even if it means by military force to get rid of him. He termed Gbagbo’s refusal of electoral defeat a ‘rape of democracy’. Odinga also condemned the ambivalence of the AU in the matter and thus called on the organization to develop teeth instead of sitting and lamenting all the time or risk becoming irrelevant.

As expected, Gbagbo did not take Odinga’s mediation effort seriously and thus, even after making several visits to the country, he did not achieve anything. In fact, Ping’ s decision to appoint a lowly premier to mediate between a president and an aspirant was questioned. In a public spat, Ping and Odinga clashed at the AU Summit meeting at the end of January 2011, when the latter accused Gbagbo of clinging to power. Odinga, who was supposed to brief the AU PSC on his mission to Côte d’Ivoire but instead decided to address the media, issued a statement observing that

Cote d’Ivoire symbolizes the great tragedy that seems to have befallen Africa, whereby some incumbents are not willing to give up power if they lose. This refusal is particularly egregious in Côte d’Ivoire’s case, since never has there been such internal, regional and international unanimity among independent institutions about the outcome of a disputed election in Africa.

With the failure of the Odinga mission, on 31 January 2011, the AU PSC established a High-Level Panel on Côte d’Ivoire, composed of the heads of state of Tanzania, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Chad and South Africa, to find a solution to the political crisis. The Panel decided to constitute a team of experts which, after visiting the country and meeting with the parties involved, reported their findings to the High-Level Panel. The Panel held several meetings in different African capitals and visited Côte d’Ivoire.

In the end, whilst the AU PSC adopted the Panel’s proposals including guaranteeing a safe-exit for Gbagbo, affirmation of Ouattara as the elected president, and formation of the unity government led by Ouattara but including former presidents of Côte d’Ivoire and people from Gbagbo’s camp, Gbagbo rejected it with his main lieutenant Pascal Affi n’Guessan observing that ‘the Panel made a proposal we categorically reject. The proposal brought nothing to the table that we did not already know’.

In the aftermath of the rejection of the Panel’s proposal by the Gbagbo camp, the PSC tasked the Chairperson of the AU Commission to appoint a High Representative (HR) for the implementation of the overall political solution (the rejected Panel s Proposal) in Côte d’Ivoire. The HR was given a two week mandate to convene a meeting between the two parties to commence negotiations particularly to develop modalities for the implementation of the proposals. The Chairperson of the AU Commission appointed former Cape Verde Foreign Minister Jose Brito as HR for the Implementation of the Overall Political Solution proposed by the AU Panel. Ouattara s camp rejected his appointment, citing his relations with Gbagbo and lack of consultations in the appointment process.

With the AU mediation effort not making any headway, the ECOWAS Authority met on 24 March 2011 and resolved that the crisis in Côte d’Ivoire had now become a regional humanitarian emergency, thus the time has come to enforce its decisions of 7 and 24 December 2010 in order to protect life and to ensure the transfer of power to Ouattara . Apropos of this, the Authority requested the UN Security Council to strengthen the mandate of UNOCI to enable it to use all necessary means to protect life and property, and to facilitate the immediate transfer of power to Ouattara.

It should be recalled that prior to the Authority s meeting, fighting between militias supporting Gbagbo and pro-Ouattara groups intensified. For example, western Côte d’Ivoire became a scene of inter-communal clashes, while fighting broke out between the Forces Nouvelles who controlled the northern part of the country and government forces. Some of the fighting resulted in human rights violations, which according to some organizations could amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Gbagbo’s ouster: On 17 March 2011, Ouattara signed an ordinance creating the Forces Republicaines de Côte d’Ivoire (FRCI), composed of the Forces armée nationales de Côte d’Ivoire and the Forces armée des Forces Nouvelles (FAFN), with the aim of undertaking a military campaign to protect the civilian populations, pacify the country and restore legality. In doing this, Ouattara had become convinced that [Gbagbo] would never cede power voluntarily and peacefully, and that all political and diplomatic efforts only served to give him more time.

The fighting pitted the FRCI against the Forces de défense et de sécurité (FDS) and the pro-Gbagbo militias. The military campaign was short and the battle for Abidjan, which began on 31 March 2011, also involved helicopters of UNOCI and the French Licorne, which were used to destroy the heavy weapons of the pro-Gbagbo camp, pursuant to UNSC resolution 1975. On 11 April 2011, the final attack was launched on the residence of Gbagbo, upon which he was arrested by the FRCI and subsequently transferred to the north of the country where he was held in detention until he was transferred to the ICC. The role of France in bringing to an end Gbagbo’s presidency was not lost to observers. France sent in scores of soldiers and some 30 armored vehicles to help arrest Gbagbo.

The arrest and detention of Gbagbo and the swearing-in of Ouattara as president of Côte d’Ivoire marked the end of the country’s post-election crisis with the AU Chairperson declaring the AU which was actively involved in the resolution of the crisis should fully play its rightful role in consolidating peace in Côte d’Ivoire. But this view was not supported by some.

Libya—The 23 February PSC Communiqué: Just one week after the Libyan crisis began, the PSC, at its 261st sitting held on 23rd February 2011, discussed the crisis and, in the ensuing communiqué, took a decision to urgently dispatch a mission of Council to Libya to assess the situation in the ground. However, there was no mission which was dispatched urgently. The failure of the PSC to act without delay set the basis upon which it came to be marginalized by the UNSC.

Had the PSC immediately established the fact-finding mission, it would have been very difficult for the UNSC to ignore it. Besides this, the Charter of the UN recognizes the existence of regional arrangements or agencies to deal with such matters relating to the maintenance of international peace and security as are appropriate for regional action, provided the activities undertaken are consistent with the purposes and principles of the UN.

Moreover, regional arrangements are enjoined to make every effort to achieve pacific settlement of local disputes through such regional arrangements before referring them to the Security Council. Thus, the failure of the PSC to immediately establish the fact-finding mission paved the way for the UNSC to pull the rug from the feet of the AU in the Libya crisis.

The AU having failed to act without delay allowed the UNSC to seize the initiative. On 26 February 2011, acting under Chapter VII, the UNSC passed Resolution 1970 which effectively precluded the AU from being the lead organization to deal with the Libya situation. Once this resolution was passed, it meant that whatever the AU would do in future regarding the Libyan situation, would be secondary to what the UNSC did; as it must be remembered that the UNSC has the primary responsibility for maintaining international peace and security. One thing is clear though, the AU opposed any use of force to remove Gaddafi.

The 10 March PSC Communiqué: The next meeting of the PSC on Libya was held on 10 March 2011 against the backdrop of fast-developing events, as Gaddafi s forces were threatening to overrun the rebel stronghold of Benghazi, while there were calls to the UNSC from the other regional bodies (such as the Arab League) to impose a no-fly zone on Libya to protect civilians. One would have expected the PSC, faced with the deteriorating situation in Libya, to act decisively, for example, by requesting an intervention from the Union in order to restore peace and security. However, the PSC did not do such a thing, but instead took two important decisions which also came to be overtaken by the UNSC action.

First, it established a roadmap through which the crisis could be resolved, including calling for: urgent African action for the cessation of all hostilities; cooperation with the competent Libyan authorities to facilitate the timely delivery of humanitarian assistance to the needy populations; protection of foreign nationals, including African migrants living in Libya; and adoption and implementation of political reforms necessary for the elimination of the causes of the current crisis.

Secondly, the PSC established an AU High-level ad hoc Committee (hereinafter ad hoc Committee) on Libya, comprised of five heads of state and government, together with the chairperson of the Commission. The committee was mandated to: engage with all the parties in Libya and to continuously assess the evolution of the situation on the ground; facilitate an inclusive dialogue among the Libyan parties on the appropriate reforms; and, engage AU s partners, in particular the Arab League (AL), the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC), the European Union (EU) and the UN, to facilitate coordination of efforts and seek their support for the early resolution of the crisis. However, as subsequent events were to show, the two decisions were overtaken by events happening elsewhere.

In the days after the establishment of the ad hoc Committee, the UNSC passed resolution 1973, which authorized member states that have notified the UN Secretary-General, acting nationally or through regional organizations or arrangements, and acting in cooperation with the UN Secretary-General, to take all necessary measures to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, including Benghazi. This paved the way for military attacks against Libya by the western powers. The resolution also imposed a no-fly zone over Libya, which meant that the ad hoc Committee could not travel to the country without UN authorization.

After passing resolution 1973, the UNSC did not pass any other resolution on Libya until September 2011 when it passed resolution 2009, which inter alia established the UN Support Mission in Libya (UNMIL). Nevertheless, various institutions of the AU continued to have their attention drawn to the crisis. For example, at its 10th meeting held on 12 May in Addis Ababa, the AU’s Panel of the Wise expressed deep concern at the situation in the country. It thus called for an immediate and complete ceasefire, and an end to all attacks on civilians.

Marginalization of the AU? If there had been any lingering doubts about the marginalization of the AU in the Libya crisis, UNSC resolution 1973 confirmed it. The resolution explicitly recognized the important role of the Arab League states in matters relating to the maintenance of international peace and security in the region. The Council only took note of the PSC’s decision to send the ad hoc Committee in its operative declaration of the resolution. In other words, the resolution recognized the primacy of the Arab League over the AU in the crisis.

Appearing on the BBC program Hard Talk on 25 March 2011, Jean Ping, the Chairperson of the AU Commission, decried the sidelining of the AU in the crisis. He raged against the fact that the international community was not consulting the AU. He said, ‘Nobody [has] talked to us, nobody has consulted us’. Asked if he felt that the AU was being ignored, he answered, ‘totally, totally’.

Nevertheless, even the Arab League became concerned with the military action in Libya once it started. In a statement on 20 March 2011, the League’s Secretary-General, Amr Musa, issued a strong statement claiming that the air strikes went beyond the scope of the resolution to implement the no-fly zone. He said he was concerned about civilians being hurt in the bombing. This raised serious concerns on the commitment of the League’s resolve and the durability of the international unity in the Libya crisis.

The final nail in the marginalization of the AU in the crisis was driven into the coffin when the UNSC refused the ad hoc Committee to fly to Libya to meet Gaddafi and the rebel leaders. On 19 March 2011, the Panel met in Mauritania’s capital Nouakchott and resolved inter alia to travel to Libya to sell to the different stakeholders the AU s roadmap to resolve the crisis.

In conformity with the requirements of resolution 1973, the ad hoc Committee sought the permission of the UNSC to travel to the country which was denied. The ad hoc Committee in its Communiqué after the meeting could only inter alia reaffirm its determination to carry out its mission in the face of the worrying developments in the situation and the recourse to an armed international intervention. It also called for restraint and undertook to spare no effort to facilitate a peaceful solution within an African framework, duly taking into account the legitimate aspirations of the Libyan people.

The ad hoc Committee, however, was able to travel to Libya from 9 to 11 April 2011, where on 10 April it met with Gaddafi, who accepted the AU roadmap on Libya including the specific issue of the ceasefire and deployment of an effective and credible monitoring mechanism. But when it went to Benghazi the next day to meet the TNC, it was a different matter. Despite extensive discussions between the Panel and the TNC, there was no agreement due to a political condition put forward by the latter as a prerequisite for the urgent launching of discussions on the modalities for a ceasefire. Thus it was not possible at that stage to reach an agreement on the crucial issue of the cessation of hostilities. The political condition advanced by the TNC was that it could not negotiate an end to the crisis unless Gaddafi relinquished power.

Underlying the TNC’s refusal to accept the AU’s roadmap there was a number of reasons. First, the AU exhibited a timid stance vis-à-vis Gaddafi as it was the only major organization that did not call for the imposition of sanctions or a no-fly zone when the crisis broke in Libya. Because of this, the opposition saw it as having no credibility and that is why it was greeted by protesting demonstrators when it arrived in Benghazi.

Secondly, there was little incentive or enthusiasm on the part of the TNC for accepting the AU’s proposition for an inclusive transition. Thirdly, the AU s roadmap received very little support from countries at the forefront of military intervention namely: France, the United Kingdom and USA. In fact, all of them called on Gaddafi to leave office and thus they were not willing to even countenance a political process that did not include the departure of Gaddafi.

In the end, the AU roadmap, which was a major political framework to end the crisis, was snubbed by the TNC because it did not mention that Gaddafi had to leave power.

Observations—Divergent positions among the AU members: The Côte d’Ivoire and Libya crises demonstrated the failure of African diplomacy. First, the crises exposed the fissures within the AU members and thus the failure of the organization to mount a united front when such challenges arise. In the Côte d’Ivoire case, conflicts among the AU members resulted in the failure of the organization to effectively deal with the issue. Whilst the AU generally concurred with the position of ECOWAS that Gbagbo be removed from power, even by force, some individual AU members took divergent positions.

For example, within ECOWAS, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Nigeria endorsed the use of force. On the other hand, Gambia recognized the legality of Gbagbo’s election and opposed the contemplated military intervention. Liberia and Mali expressed concern over the consequences of the military intervention. In fact, the latter’s President Amadou Toumani Toure averred that when Côte d’Ivoire has a cold, the whole of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA) starts sneezing. Thus he expressed preference for financial pressure over [military] intervention.

Far afield, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, called for an investigation of the election process and rejected the validity of international recognition of Ouattara and its dismissal of Gbagbo s claimed win. Angola came out strongly to support the government of Gbagbo, while South Africa, one of the first mediators in the dispute opined that the poll discrepancies marred the vote and so mediation between the parties was the answer.

The same thing happened in the Libya case where three positions emerged among the members to deal with the situation. The first position advanced by inter alia Uganda, South Africa and to an extent Kenya, accepted UN Resolution 1973 in principle, but was critical of the way the NATO countries were conducting their operations in Libya. To these countries, NATO s operations went beyond the contours of Resolution 1973 and in effect were part of the regime change doctrine.

The second position, advanced by the likes of Ethiopia, Gabon, Rwanda and Senegal, supported the NATO attacks on Libya, with President Kagame, in particular, arguing that ‘the Libyan situation had degenerated beyond what the AU could handle’. The third position which was really not different from the first, and advanced by the likes of Zimbabwe, Algeria and Nigeria, opposed NATO s operation in Libya and viewed it as Western countries using the UN to get rid of the Gaddafi regime. In fact, President Mugabe accused NATO of being a terrorist organization fighting to kill Gaddafi. So with these varied positions, the AU could not mount an effective intervention in the crisis.

Failure to take a position on the future of Gbagbo and Gaddafi: Under the AU plan for resolving the Côte d’Ivoire crisis, Gbagbo would be given safe passage into exile with his party being part of the national unity government. But South Africa, a member of the AU Panel on Côte d’Ivoire, did not agree with this position. In fact, its position as stated by the Vice-Foreign Minister Ibrahim Ibrahim on 22 February 2011 was that a power-sharing formula be crafted, which would involve rotating power with a 24 month period for each of the two presidents. Other countries, such as Gambia, came out strongly in support of Gbagbo. In the end, the diverging positions on Gbagbo’s future muddled the diplomatic situation and thus gave him more time in the presidency.

In the case of Libya, the AU failed to pronounce itself on the future of Gaddafi in and after the negotiation of the political solution to the crisis. While western permanent members of the UNSC—France, United Kingdom and the United States—were resolute in their demand that Gaddafi relinquish power, the AU was ambivalent on the issue. Asked if Gaddafi had to leave power, President Jacob Zuma was of the view that if he (Gaddafi) had to go, the issues to be addressed were when, where and how that happens.

At the 17th AU Summit meeting in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, some African officials announced that Gaddafi should surrender power in order for a democratic transition to take place. The UK s Minister of the UN and Africa, Henry Bellingham, was quoted saying that most foreign ministers at the Malabo meeting were telling him privately that they felt Gaddafi should go. But the final decisions of the Assembly on Libya called for no such action.

Moreover, being the only major organization that had not called for the imposition of sanctions or a no-fly zone on Libya, the AU carried very little credibility especially with the rebels. This could partly explain why they (the rebels) were reluctant to buy into its political roadmap.

The AU overtaken by events: As we noted in the introduction, forces loyal to Ouattara launched an offensive to remove Gbagbo from power at the end of March 2011. On 11 April 2011, they managed to enter the presidential palace in Abidjan and arrested Gbagbo. Thereafter he was placed under detention, first in Abidjan s Hôtel du Golf, and later at Korhogo, in the north of the country, under the protection of UNOCI. At the end of November 2011, Gbagbo was transferred to The Hague and placed in the custody of the ICC. This was the result of a warrant of arrest requested by the ICC Prosecutor on 25 October 2011, and issued by the court under seal on 23 November 2011. Gbagbo is facing four counts of crimes against humanity.

As we noted above, French troops played a key role in the final ouster of Gbagbo, especially through the airstrikes they carried out against heavy weapons belonging to troops loyal to him. In the aftermath of Gbagbo’s ouster, the AU was left to finally declare that ‘the country [was] back to normal institutional situation, with the restoration of legality throughout the national territory’. The organization triumphantly noted that ‘it had played an active role in the resolution of the crises’.

But had it? From the exposition that we have made above, the organization s mediation efforts were rebuffed time and again by the interlocutors in the Côte d’Ivoire crisis. At some point during the crisis, the AU mediation efforts resulted in the stifling of the ECOWAS resolve to use military force to oust Gbagbo. Therefore we are left to contemplate on what may have been had ECOWAS been allowed to deal with the issue.

In the case of Libya, on Sunday 21 August, rebels launched an offensive to take Tripoli from Gaddafi s forces. They made rapid progress and by the end of the week had overrun much of the capital although sporadic fighting continued in parts of the city. Whilst Gaddafi went into hiding, he continued making radio broadcasts urging his followers to fight and take back the city.

The AU ad hoc Committee and the PSC met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, to craft a response regarding the events in Libya. In the final communiqué of its 291st meeting, the PSC declined to recognize the TNC as the legitimate authority in Libya. Citing Article 30 of the Constitutive Act of the AU which bars governments which come to power through unconstitutional means from participating in the activities of the organization, the PSC reaffirmed its stand that all the stakeholders in Libya come together and negotiate a peaceful process.

This position would involve the inclusion of elements from the Gaddafi regime to be part of the new government. But again the fissures that characterized the AU s intervention in the crisis continued. Whilst the ad hoc Committee and the PSC deliberated on the need for the formation of an all-inclusive transitional mechanism to lead Libya in the interim as a new Constitution is drafted to provide for elections, the governments of Ethiopia and Nigeria recognized the TNC as the authority in charge of Libya.

Nigeria s move irked South Africa, prompting the Secretary-General of the African National Congress (ANC), Gwede Mantashe, to criticize the country by declaring that it was jumping the gun in recognizing the rebels as representatives of Libya In reply, President Goodluck Jonathan affirmed that his government stood by the recognition of the NTC (sic) and that Nigeria’s foreign policy would not be dictated to her by the government, party or opinion of another country.

Nigeria s recognition of the TNC could have been prompted by Gaddafi s past pronouncements on the country. In March 2010, Nigeria recalled its ambassador to Tripoli following Gaddafi’ s call for Nigeria to be split into two one Christian and another Muslim in the wake of massacres in the northern Nigeria city of Jos. Rwanda had earlier also broken ranks with the AU position by reiterating its unequivocal support to the TNC.

Whilst, up to that point, altogether there were eleven AU members that recognized the TNC, another 41 states had declined to recognize it—thus further deepening the divisions within the organization in the crisis.

In the end, taking cognizance of the situation on the ground in Libya, and the fact that the TNC had been welcomed at the UN General Assembly, President Teodore Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, President of Equatorial Guinea and Chairman of the AU in late September 2011, announced the recognition of the TNC as the representative of the Libyan people provided they formed an all-inclusive transitional government which would occupy the Libyan seat at the AU.

Of course, the TNC did not establish an all-inclusive government. Nevertheless, with the demise of Gaddafi and the declaration that Libya was totally liberated, the AU had no choice but to recognize and deal with the TNC. This marked the end of the AU diplomatic efforts to end the Libya crisis.

Conclusion: The formation of the AU was precisely aimed at finding African solutions to African problems. The experiences of Somalia and Rwanda in the early 1990s, where state collapse and genocide were allowed to take place respectively, spurred on the African leadership to establish an AU with teeth.

In this regard, the African leadership adopted a much more interventionist stance in the organization s legal frameworks and institutions. However, the Côte d’Ivoire and Libya crises showed that the organization is far from being a solution to the problems afflicting Africa. Its performance in the Côte d’Ivoire crisis was lackluster while in the case of Libya, it was first marginalized and then totally ignored by the UN.

Generally in both cases the organization s failure was self- inflicted because had it taken very strong, united and assertive stances when the crises first broke out, possibly it would not have been marginalized and ignored by the other actors.

In the end, in both cases, the organization was saddled with problems, inter alia of fissures within its ranks resulting in its intervention being feeble. Its members did not speak with one voice, as is often the case, on many issues concerning the continent.

Dr Kasaija Phillip Apuuli teaches in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University, Kampala. He wishes to thank Ben Kioko, the AU Legal Counsel, for important insights on the AU s reaction in the Côte d’Ivoire and Libya crises.

Dr Kasaija Phillip Apuuli teaches in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University, Kampala. He wishes to thank Ben Kioko, the AU Legal Counsel, for important insights on the AU s reaction in the Côte d’Ivoire and Libya crises.