PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

What Made This Man Betray His Country?

DAVID E. HOFFMAN AUG 8, 2015, THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY

How a troubled past turned a Soviet military engineer into one of the CIA’s most valuable spies.

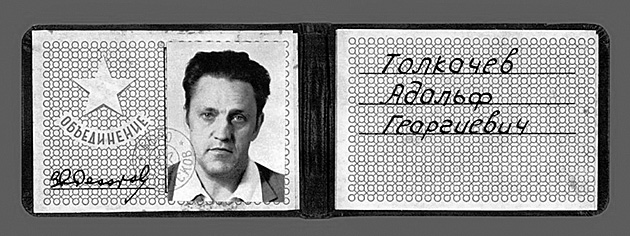

Adolf Tolkachev, a Soviet military engineer and CIA spy, in 1984Courtesy of a family friend / The Billion Dollar Spy

His family and friends called him Adik. His eyes were the color of ash, under a broad forehead and thick brown hair, with a crook in the bridge of his nose from a boyhood hockey accident. He stood about five feet six inches tall. Adolf Tolkachev seemed a quiet fellow to those who knew him. He was so reserved that he never told his son what he did at work, in a Soviet military-design laboratory where he specialized in airborne radar.

But his mind was not at ease. He was haunted by a dark chapter of Soviet history, and he wanted revenge.

His anger drove him to become the most successful and valued agent the CIA had run inside the Soviet Union in two decades. The documents and drawings he passed to the United States in the early 1980s unlocked the secrets of Soviet radar and revealed sensitive plans for research on weapons systems a decade into the future. His espionage put the United States in position to dominate the skies in aerial combat and confirmed the vulnerability of Soviet air defenses—that American cruise missiles and bombers could fly under the radar.

As in many other areas of technology, the Soviet Union was struggling to catch up to the West. In the early 1970s, Soviet airborne radars could not spot moving objects close to the ground, meaning they could fail to detect a terrain-hugging bomber or cruise missile. This vulnerability became a major design challenge for Tolkachev and the engineers he worked with; they were pressed to build radars that could “look down” from above and identify low-flying objects moving against the background of the earth. The United States was planning to use low-flying, penetrating bombers to attack the Soviet Union in the event of any war. Tolkachev had joined the Scientific Research Institute for Radio Engineering, later known as Phazotron, in the 1950s as it was expanding into research and development of military radars, which grew in sophistication from simple sighting devices to complex aviation and weapons-guidance systems. It was the only place he had ever worked.

Tolkachev was 54 years old in 1981. He suffered from high blood pressure and tried to pay attention to his health. He drank alcohol only rarely. He was usually up before dawn, especially in the long winter, according to letters he wrote to the CIA. Every other day during the week, he got out of bed at 5:00 a.m. and went for a run outdoors, if it wasn’t raining or biting cold. In one letter to the CIA, he described himself as a morning person. “You probably know,” he wrote, “that people are sometimes divided into two different types of personalities: ‘skylarks’ and ‘owls.’ The first have no trouble getting up in the morning but start getting sleepy as evening approaches. The latter are just the opposite. I belong to the ‘skylarks,’ my wife and son to the ‘owls.’”

Tolkachev lived in a comfortable apartment in a building he shared with the Soviet aviation and missile elite. His neighbors included Valentin Glushko, the principal designer of Soviet rocket engines, as well as Vasily Mishin, who led the Soviet effort, ultimately unsuccessful, to build a lunar rocket. But Tolkachev was a loner. He had once socialized with workers at his laboratory, he told the CIA, but now, “possibly because of age, all these friendly conversations started to tire me and I have practically ceased such activities.” Above Tolkachev’s kitchen door was a crawl space where he stored his camping tent, sleeping bags, and building materials—as well as his spy equipment from the CIA. His wife Natasha, slightly shorter than Adik, was not agile or tall enough to reach it, and his son Oleg had no reason to.

Adik and Natasha lived and worked in the closed cocoon of the military-industrial complex, a sprawling archipelago of ministries, institutes, factories, and testing ranges. Tolkachev had the highest-level access to state secrets. Their public behavior was governed by survival in the Soviet party-state system, which dictated conformity. By day, they played by the rules. By night, their private feelings were vastly different.

Their thinking was forged in the sorrow and loss of Natasha’s childhood, which she had spent without parents due to Joseph Stalin’s purges, a loss that propelled Adik into the world of espionage. After a series of show trials in Moscow beginning in 1936, the purges sliced through the party elite, and expanded later in the summer and into the autumn of 1937 with wave after wave of suspicion, denunciation, arrest, and execution. One of the largest was the kulak operation, referring to the more prosperous farmers who had been forced off their land during Stalin’s disastrous forced collectivization of agriculture, with more than 1.8 million of them sent to prison camps. When the kulaks neared the end of the standard eight-year prison term, Stalin feared a wave of disgruntled and embittered people coming home. The hammer fell with a secret police order, No. 00447, in July 1937, which set the pattern for the mass killings of the following two years. The document ordered arrests by quota—thousands and thousands at a time—in specific categories such as “kulaks, criminals and other anti-Soviet elements.” The categories were so broad as to apply to almost anyone. People were arrested and executed for the slightest indiscretion, so they became extremely guarded in what they said in public; a single stray comment could be reported and lead to arrest, with the charges entirely arbitrary.

There was so much paranoia that anyone who visited or knew someone who lived abroad could be suspected of being an enemy of the people. Denunciations were often made recklessly and maliciously, and could quickly lead to death. “Today, a man only talks freely with his wife—at night, with the blankets pulled over his head,” said the writer Isaac Babel, who himself was arrested in the spring of 1939, charged with anti-Soviet activity and espionage, and shot in 1940.

Natasha was two years old when her mother, Sofia Efimovna Bamdas, a Communist Party member and head of the planning department in the Ministry of the Timber Industry, was arrested and executed. Sofia had been accused of subversion after visiting her father, a successful businessman in Denmark. He was a capitalist and a foreigner, more than enough to generate suspicion. Natasha’s father, Ivan Kuzmin, who had refused to denounce his wife, was later taken to Moscow’s notorious Butyrskaya Prison and charged with participation in an anti-Soviet terrorist organization. He was sent away to a labor camp. Natasha was delivered to one of the state orphanages, which in those years were overflowing due to the sheer number of people who had been declared “enemies of the people.” She did not see her father again until she was 18; three years later, he was dead of a brain disease in Moscow.

Natasha married Adolf Tolkachev in 1957, the year after her father died. She managed to stay out of trouble, but those who worked with her knew of her feelings. She read the banned writer Boris Pasternak and the poet Osip Mandelstam. When Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was published in 1962, she was the first in the family to devour it. Later, when possession of Solzhenitsyn’s unpublished works was more dangerous, she was unafraid to pass around copies in samizdat, the underground distribution network for banned literature. In 1968, after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, there was a rush in Soviet workplaces to pass resolutions supporting the action. She was the only person in her group to vote no. She was, in the words of a supervisor, “unable to be insincere.” Her long ordeal and her deep antipathy to the Soviet party-state became Tolkachev’s, too.

* * *

The painful history of the Kuzmin family was passed down to Natasha—and to Adik—in her father’s last years. Ivan told his daughter the unvarnished truth: the terror of the arrests, the finality of the verdicts, the sudden destruction of their family. By the time Adik and Natasha married, the threat of Stalin’s mass repressions had passed, but strong memories lingered, and the full scope was only beginning to reveal itself. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev devoted a speech to Stalin’s excesses at the 20th Party Congress on February 25, 1956, blaming Stalin for the unwarranted arrest and execution of party officials during the purges, for Hitler’s surprise attack on the Soviet Union, and for other blunders, although not for the true scope of the repressions or the forced collectivization and famine, calamities for which Khrushchev shared responsibility. Nonetheless, Khrushchev had opened the door; he denounced the “cult of personality” that had allowed Stalin to amass such raw power. The speech heralded a period of liberalization known as the “thaw.”

Breaking with years of forced adherence to the dictates of socialist realism, some freethinking writers and artists dared push the boundaries of what was permissible, and hopes ran high that a different country might emerge from the Great Terror and the ravages of war. The Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite in October 1957 fueled the optimism, especially among young people. Lyudmila Alexeyeva, a historian and human-rights champion, recalled that in the years that followed Khrushchev’s speech, “Young men and women began to lose their fear of sharing views, knowledge, beliefs, questions. Every night, we gathered in cramped apartments to recite poetry, read ‘unofficial’ prose, and swap stories that, taken together, yielded a realistic picture of what was going on in our country. That was the time of our awakening.” The awakening undoubtedly swayed Adik and Natasha, too.

Tolkachev told the CIA that “in my youth” politics had played “a significant role,” but he had lost interest and then become scornful of what he called the “impassable, hypocritical demagoguery” of the Soviet party-state. He did not elaborate on this change, but by the mid-1960s, as the thaw was ending and with Khrushchev deposed, Tolkachev seems to have been thinking about how to express his unhappiness.

In the mid-1970s, Tolkachev found inspiration in Andrei Sakharov and Alexander Solzhenitsyn, voices of conscience who each waged a titanic struggle against Soviet totalitarianism. Sakharov, like Tolkachev, had a top-secret security clearance, yet he possessed the courage to dissent. Tolkachev did not know him personally but knew what he stood for.

In the early months of 1968, Sakharov had worked alone, late into the evening, at his gabled, two-story house at a nuclear-weapons laboratory 230 miles east of Moscow. Sakharov was the principal designer of the Soviet thermonuclear bomb. A pillar of the scientific establishment who entered the Academy of Sciences in his 30s, he had profound doubts about the moral and ecological consequences of his work, and he played a role in persuading Khrushchev to sign a limited nuclear test ban treaty with the United States in 1963. Now his conscience was calling him again and would take him well beyond the closed world where he had thrived and been recognized as a brilliant physicist.

Each night, from 7:00 until midnight, alone in the house in the woods, Sakharov worked on an essay about the future of mankind. It became his first significant act of dissent against the Soviet system. Finished in April, the essay was titled “Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom.” Sakharov’s mind ranged far and wide, warning that the planet was threatened by thermonuclear war, hunger, ecological catastrophe, and despotism, but he also offered idealistic and utopian ideas to save the world, suggesting that socialism and capitalism could live together—he called it “convergence”—and that the superpowers should not be trying to destroy each other. He wrote candidly of Stalin’s crimes. The document was startling, visionary, and potentially explosive. In July, the manifesto was published abroad, first in a Dutch newspaper and then in The New York Times. The essay also circulated widely in samizdat inside the Soviet Union. Sakharov was then suspended—effectively fired—from his job at the nuclear-weapons laboratory.

Only weeks later, on August 20-21, 1968, Soviet tanks and Warsaw Pact troops crushed the reform movement known as the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia. Sakharov had been excited by the democratic experiment; the Soviet crackdown shattered his optimism. “The hopes inspired by the Prague Spring collapsed,” he said. The thaw was over.

* * *

Among those who read Sakharov’s “Reflections” was Solzhenitsyn, whose penetrating novels had depicted the dark corners of Soviet totalitarianism. His novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, about the life of a man in the gulag, had been published in Russian during the thaw, but his more recent works, Cancer Ward and The First Circle, were banned, and he was increasingly a thorn in the side of the Soviet authorities. Sakharov had come from deep within the establishment and Solzhenitsyn from without; both men became beacons of inspiration for Tolkachev.

In the early 1970s, Sakharov plunged more deeply into the struggle for human rights in the Soviet Union, and began broadening his personal contacts with Westerners, a move that infuriated Soviet officials who had, until then, treated him with restraint. In July 1973, a Swedish newspaper published an interview in which Sakharov was scathingly critical of the Soviet party-state for its monopoly on power and most of all “the lack of freedom.” The interview made headlines around the world. The party-state took off the gloves. A sustained and ugly press campaign was waged against Sakharov. Forty academicians signed a letter saying Sakharov’s actions “discredit the good name of Soviet science.” Solzhenitsyn, who had won the Nobel Prize in Literature but was unable to receive it in person, urged Sakharov to keep a low profile; the regime was on the offensive against him and the broader human-rights movement. The KGB warned him not to meet with foreign journalists, but days later he responded by inviting foreign correspondents to his apartment for a press conference at which he repeated his views on democratization and human rights.

Meanwhile, Solzhenitsyn’s exposé of the Soviet prison camps, The Gulag Archipelago, was being readied for publication in the West. Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn had ignited a fire, and the KGB began to speak of them in the same breath. In September 1973, Yuri Andropov, the KGB chief, recommended taking “more radical measures to terminate the hostile acts of Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov.” In January 1974, Solzhenitsyn was arrested and deported from the Soviet Union. In 1975, Sakharov received the Nobel Peace Prize but was prohibited from leaving the country to receive it.

These events left a deep and lasting impression on Tolkachev. When he later recounted his disenchantment to explain his actions to the CIA, he identified 1974 and 1975 as a turning point. After years of waiting, he decided to act. “I can only say that a significant role in this was played by Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov, even though I don’t know them,” he wrote in a letter to the CIA.

“Some inner worm started to torment me,” he said. “Something had to be done.”

Tolkachev began his expression of dissent modestly, by writing short protest leaflets. He told the CIA he briefly considered sending the leaflets in the mail. “But later,” he added, “having thought it out properly, I understood that this was a useless undertaking. To establish contact with the dissident circles that have contact with the foreign journalists seemed senseless to me due to the nature of my work.” He had a top-secret clearance. “Because of the slightest suspicion, I will be totally isolated or liquidated for safety.”

Tolkachev decided that he would have to find other ways to damage the system. In September 1976, he heard on a radio broadcast that a Soviet fighter pilot had defected by flying his MiG-25 interceptor to Japan. When the Soviet authorities ordered Phazotron to redesign the radar for the MiG-25, Tolkachev had a dawning realization. His greatest weapon against the Soviet Union was not some dissident pamphlets but right in his desk drawer: the blueprints and reports that were the most closely held secrets of Soviet military research. He could seriously injure the system through betrayal, turning these vital plans over to the “main adversary”: the United States.

Tolkachev told the CIA he had never even considered selling secrets to, say, China. “And how about America, maybe it has bewitched me and I am madly in love with it?” he wrote. “I have never seen your country with my own eyes, and to love it unseen, I do not have enough fantasy nor romanticism. However, based on some facts, I got the impression, that I would prefer to live in America. It is for this very reason that I decided to offer you my collaboration.”

Tolkachev was usually at his desk at Phazotron by 8:00 a.m., but he did a lot of his best thinking outside the office. He often found inspiration at home or sitting alone in the early evening in the Lenin Library. He jotted down notes, then took them to work and copied them into a special classified notebook, which was turned over to the typing pool.

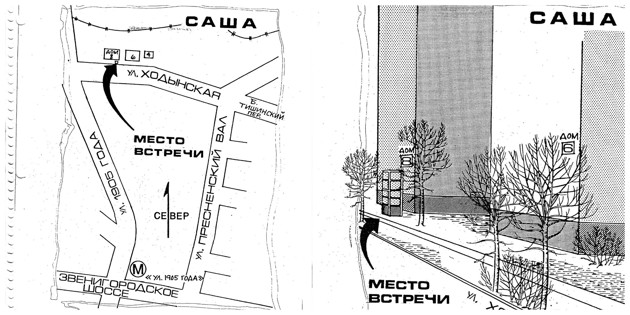

Tolkachev realized there was a security gap at Phazotron, and he took advantage of it for his espionage. He would leave the office during the lunch hour with secret documents tucked inside his coat, and make the 20 minute walk to his empty apartment. There, he would take out the Pentax camera given to him by the CIA, clamp it to the back of a chair, position a lamp nearby, and make copies of documents. He would return the documents to the office after lunch. He gave the film to the CIA over the course of 21 meetings on the streets of Moscow.

One day in 1981, Tolkachev was careless. After finishing his work, he usually stowed his camera and clamp in the crawl space above the kitchen door, where they would be well-hidden. But this time he hastily left them in a desk drawer. They were discovered by Natasha, and she immediately guessed what Adik was doing. She confronted him when they were alone.

Her concern was not the damage he was doing to the Soviet state. She hated the system even more than Adik did. But she did not want their family to get hurt in the way that her parents had. She did not want to bring the wrath of the KGB upon them.

Tolkachev confessed to her. She demanded that he stop his spying, to spare the family any difficulty, and he promised to quit. But he did not. He continued to provide top-secret documents to the CIA, but in late 1984 and early 1985, he was betrayed to the KGB. (CIA officials believe the informant was Edward Lee Howard, a one-time CIA trainee who had been fired after failing a series of polygraph tests. Howard, who defected to the Soviet Union after Tolkachev’s arrest, denied betraying the Soviet spy. Howard died in Moscow in 2002.) Tolkachev was arrested in 1985, interrogated, and tried by a military tribunal for treason. The Soviet news agency Tass announced on October 22, 1986 that he had been executed.