PBS: Escaping Eritrea … [Read More...] about ካብ ውሽጢ ቤት ማእሰርታት ኤርትራ

The Black Cloud in Africa

Evans Lewin, July 1926 Issue, Foreign Affairs

DEAN INGE in a more than usually gloomy and brilliant article in the Luarterly Review [sic] in which he shows, more particularly with reference to Asiatic civilization, the menacing dangers that threaten the survival of European control in the East, and even Europe itself, has pointed out that “the suicidal war which devastated the world of the white man for four years will probably be found to have produced its chief results, not in altering the balance of power in Europe, but in precipitating certain changes which were coming about slowly during the peace.” In no part of the world is this more true than in Africa.

The basis of racial supremacy throughout the whole of Africa, tropical and sub-tropical, as in India, rests upon the consent of the governed, and only to a limited extent upon the application of those superior material means of enforcing his will that civilization has placed in the hands of the white man. Without the willing cooperation of native races all attempts to compel obedience must fail inevitably in their ultimate and highest object, which is the uplifting of the great and hitherto inert masses of the African peoples to a higher plane of civilization.

White supremacy in Africa, if it be attacked at all, will not be threatened in those vast intermediate areas, sweltering under the tropical sun, which lie between the two fringes of white colonization in the north and south of the continent, but in those more favored regions where white settlement is possible and where Europeans have erected a substantial civilization — in the north upon the ruins of the ancient Roman and Arab cultures, and in the south in regions where the black man was in a state of semi-savagery when Europeans first set foot in his territories.

Two distinct problems are created through the impact of the white man upon the black. In the tropical portions of the continent, where the black man is in an overwhelming majority and where the white man merely acts as the director and pioneer of civilization, it is possible for the native to retain in a large measure his own cultural environment without being cut off from the ties of the past which bind him to his own people and serve to develop his own methods of thought, and without being swallowed by a new and alien civilization imposed upon him from abroad. He can adopt, and generally does adopt, just so much of European methods and civilization as are suited to his advance upon the paths of his own culture. He still remains among his own people, able to influence them for good or ill and to be influenced by them in return. Above all, he can rise in the scale of civilization without let or hindrance from the white man. At no point does he come into active conflict with economic or social factors that he is unable to understand; and, although acting frequently under European guidance, he is still master in his own house and suffers under no intolerable racial disadvantages.

In the more temperate portions of the continent, on the other hand, where the white man has established industries and built large cities, the native has come into direct contact with economic and social forces which, while they may help his material development, generally tend to retard his spiritual and cultural advancement. He is a social outcast. If he attain some degree of the higher culture of those who have opened new avenues of educational advance, he is unable to make effective use, in the service of the whole community, of the knowledge he has assimilated by slow and painful processes and in spite of the almost overwhelming prejudices, well founded or otherwise, that are arraigned against him. In a country of white settlement he is faced by the inertia of racial antipathy and is met everywhere by a stubborn and ineradicable opposition, should he attempt to climb into the preserves of the white man. Politically he does not count; socially he cannot mix on terms of anything approaching equality with the white man. He is not permitted to enter a church attended by Europeans, and he is doomed to remain a “hewer of wood and drawer of water” because all avenues of economic advance are closed upon him.

The problems, therefore, in tropical and sub-tropical Africa are entirely different. In the former the black man is free to work out his own destinies. In the latter he is at the beck and call of the European and, under present conditions, cannot, even if he would, evolve his own type of civilization; he is racially but not yet economically segregated. It is this profound difference between the treatment accorded to the black man in tropical Africa and in South Africa that is bringing about the pressing problem of the present age in Africa known generally as the “color question.”

Prior to the war there was an uneasy stirring of the black masses of humanity who were being slowly influenced by the penetrating genius of the European races. Vast and important changes were being brought about by the gradual, but not too rapid, economic development of African countries. Missionaries, traders, and administrators were performing their allotted tasks well or indifferently well, or even badly in some cases, in the midst of primitive peoples who were only slowly awaking to the nature of the new methods being introduced among them.

The war, however, set in operation new and perplexing influences in Africa. Not only did the African races see thousands of white men, professing the Christian religion, engaged in a deadly struggle upon African soil, especially in such regions as the Cameroons, German East Africa, and German South-West Africa — a struggle with its inevitable reactions in other parts of the continent — but they witnessed great numbers of their own race entering upon this fight on one side or the other and also leaving Africa itself to assist their masters in the main theatre of the war. The French native troops who were withdrawn from West Africa and the northern protectorates, and the natives who left South Africa for employment on the lines of communication in Europe itself, must have returned with enlarged ideas of the prowess of the white man but with a changed view of his cultural and spiritual superiority; and the repercussions throughout Africa of the ideas thus engendered have had far-reaching and important results.

It may be stated as a general axiom that Christianity as preached by the missionaries has received a setback wherever native Africans have come into direct contact with Europeans. The black man has come more and more to realize that precept and practice are not the inevitable accompaniments of European civilization. But of one fact he is still generally convinced, more particularly in the tropical portions of the continent. He believes that Europeans, as a whole, are desirous of helping him to rise in the scale of civilization, and that in spite of certain ugly economic factors an outstanding feature of European control is the idea of trusteeship, held by most administering nations, on behalf of the native races that have fallen under their charge.

This conception of “trusteeship” as presented to the African peoples is not a new one. It goes back at least as far as the great movement which ended in the abolition of slavery, though until recently it has been but a still small voice crying in the wilderness of the somewhat ineffective, and certainly self-interested, administration that was introduced into numerous African territories when the race for African land first assumed considerable proportions in the ‘eighties of the last century. It is, however, one of the most satisfactory features of the new administrative policy that has come to the front since the war that this underlying principle has been recognized officially as the guiding force of European effort in tropical Africa. While, on the one hand, economic penetration and development is undoubtedly the factor that causes European governments to shoulder the vast responsibilities of administrative work in Africa, on the other, the recognition of these responsibilities has become an essential feature of government; and African natives in the tropics have not been slow to appreciate all that is involved in this new orientation of European policy.

In all British colonies and protectorates in Africa the doctrine of trusteeship has been firmly laid down as a guiding principle of government. The Kenya White Paper of 1923 stated that the basis of our position in East Africa is the duty of trusteeship for the native population under our charge, and this duty has been emphasized more recently by Mr. Ormsby Gore, Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, in the remarkable report of the East African Commission. He states that “it is difficult to realize without seeing Africa what a tremendous impact is involved in the juxtaposition of white civilization, with its command over material force, and its comparatively high and diversified social system, on the primitive people of eastern Africa. The African native is confronted with a whole range of facts entirely beyond his present comprehension and he finds himself caught in a maelstrom of economic and cultural progress which in the majority of cases baffles him completely.” He then goes on to say that “the status of trusteeship involves an ethical conception; that is to say, it imposes upon the trustee a moral duty and a moral attitude. This derives in part from the influence of Christianity upon western civilization, and in part from what is claimed to be a specifically British conception, namely that of ‘fair play for the weaker’.” A great African administrator, Sir Frederick Lugard, has pointed out that this trusteeship involves a double duty. “We are not only trustees for the development and advance in civilization of the African, but we are also trustees for the world of very rich territories. This means that we have a duty to humanity to develop the vast economic resources of a great continent.” It is precisely how far these two conceptions can be embodied in a harmonious policy, fair alike to the natives, to white settlers where they exist, and to the outside world, that constitutes to-day the problem of tropical Africa.

British policy in Africa may perhaps be best exemplified by a study of the work being done in the two West African colonies of the Gold Coast and Nigeria and in Uganda and the Kenya Colony. In no part of tropical Africa are the natives generally so far advanced on the paths of civilization as they are in the Gold Coast, Nigeria, and Uganda, and the main reason for this advance is that not only was there a foundation of native civilization upon which to erect the present edifice but the native has been left under suggestive guidance to work out his own salvation. His lands have not been alienated, his tribal system has not been broken up, and no attempt has been made to force upon him alien methods of government or to turn him into a mock Englishman. Compared with German administration in the Cameroons, where a strictly plantation system was followed and where the tribal lands frequently fell into the hands of speculating companies and private individuals, the system has proved a distinct success.

At the basis of all prosperity and contentment in Africa is the land question. Where the native has obtained security of tenure, either on a community basis or as a private owner, there is unlikely to be any serious attempt to question the right of the European to control. It is only where, as is frequently the case in South Africa, the native has been de-tribalized and is a “landless” man, that serious unrest is likely to occur — assuming, of course, that the natives have passed out of the purely savage state. In the Gold Coast, the natives, almost by their unaided efforts, have built up a great cocoa industry, which now supplies half the world with its cocoa, worked entirely by native cultivators and owned by native peasant proprietors. Similarly in Nigeria, the natives own their own land and are encouraged to work out their own salvation. In Uganda also a great cotton-growing industry has been established by the natives, worked and owned entirely by them. It is not in every part of Africa, however, that native peasant proprietorship is possible or, perhaps, desirable; and it is precisely where the natives are too backward in civilization to adopt readily the methods that have been so successful elsewhere that other means, such as European plantations, must be tried. Here the largest amount of unrest in the near future is to be expected.

British policy in Africa generally is to establish control by means of what is generally termed “indirect rule,” that is to say, so far as possible the prestige of the native chiefs is maintained and extended and the people are ruled mainly through their hereditary or chosen leaders. Though some individuals do, perhaps not unsuccessfully, break away from their tribal surroundings and influences and ape the Englishman, especially in the coastal towns, the vast majority still retain all that is best in their native cultures and gradually take from European civilization the things best suited to their own mental and cultural development. In comparison of French and British methods in this respect it need only be said here that while the French are eminently successful as administrators in Africa, their policy is intensely nationalistic and makes for unity of administration rather than for diversity. The Frenchman looks upon his colonies as forming part of France and the native is trained to look upon himself as a Frenchman. In the British colonies, on the other hand, the natives remain to all intents and purposes sons of the soil that gave them birth.

At the back of all progress in tropical Africa is the question of education. Recently an American Commission under Dr. Thomas Jesse Jones, sent out by the Phelps-Stokes Fund, has reported on this subject, and though the conclusions of the Commission are not to be accepted in all cases without demur, it has undoubtedly performed a most useful work in a hitherto almost unexplored field. It is remarkable that both so much and so little has been done in the educational sphere in Africa. In some cases, apart from missionary endeavor, very little has been achieved and that, not infrequently, upon wrong lines. It seems to be admitted universally, however, that the bad old system of a purely literary education only survives in regions where the authorities, and the missionaries themselves, have not been awakened to what should be the true purpose of native education. The Phelps-Stokes Commission has plainly indicated that in its opinion, while a literary education may well form the apex of the system, the main purpose of African training should be to instruct the natives how to use their lands, their hands, and their intelligence. In other words training in agriculture, in craftsmanship, in hygiene, is quite as essential as a knowledge of reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Up to the present agricultural and craft education have been much neglected, although definite steps have been taken in many cases to show the native how essential these subjects are to his well-being. It is almost incredible that in the whole of Africa there is, apparently, but one school that is exclusively engaged in teaching agriculture to natives and it is, perhaps, the more remarkable that this institution, the Tsolo Agricultural School, is situated in South Africa and is supported by funds supplied by the native Bhunga, a council of the native Transkeian Territory of the Cape Province. Such establishments should be everywhere in Africa to supplement the work of the ordinary schools, and the funds used to spread education, and especially to educate native teachers, should be increased at least tenfold in every colony in Africa. Efficient education — not mere book learning — and native tenure of land, will do everything to stabilize the position of the European as the controller of the destinies of tropical Africa.

The status and prospects of the native present a different picture in that portion of the continent where he comes into direct contact with European civilization in, to him, some of its ugliest and most detrimental forms. It is not easy for those who have not lived in the Union of South Africa to visualize the position of the natives in those provinces. The problems are so complex, the danger is so pressing, the outlook is so uncertain, that one may be pardoned for taking a gloomy view both of the future of the white race in the sub-continent and the future of the natives themselves. To state the position frankly and concisely, it must be admitted that the impact of European civilization upon the natives in South Africa in certain respects, though fortunately not in all, has been disastrous, because there the native can only be assimilated into the social system as a helot rather than as a sharer in the full benefits of white civilization.

The problem may be approached from two points of view: the result upon the white population of a preponderating black element in a country otherwise eminently suitable for European settlement, and the effect upon the natives of the conditions by which they have been gradually surrounded and into which they are continuously being drawn. The black man in South Africa is a man entrapped. The white man is tending to become an aristocrat in the center of a civilization that may be compared with the slave-holding states of antiquity and where in the future he may only remain as a master existing on the sufferance of his servants. Sooner or later his position, unless he take effective steps to alter his present policy, will be comparable with that of Europeans settled in the West Indies, and he will be swamped by an ever-swelling tide of black humanity.

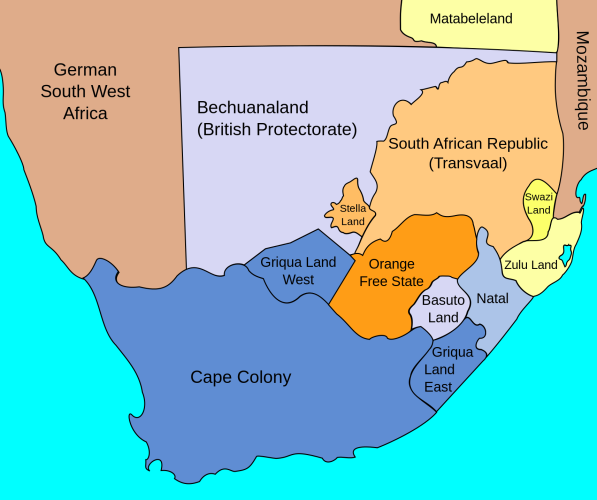

In the Union of South Africa there are at present some 5,404,000 non-Europeans, of whom 4,698,000 are pure Bantus, compared with a white population of 1,522,000. In addition there are 497,000 natives in Basutoland, 150,000 in the Bechuanaland Protectorate, and 112,000 in Swaziland, three native territories under the direct rule of the Colonial Office, the control of which is urgently desired by the Union Government. There is thus a total native and colored population of 6,163,000 who are increasing at a much more rapid ratio than the Europeans. The former Director of the Census, Mr. Cousins, has pointed out that the European race can only hold its own numerically in South Africa by seeking accessions from abroad and that failing a constant immigration it must abandon the prospect of maintaining a white civilization, except as a diminishing minority in face of an overwhelming majority. It may then, he thinks, be forced to give up its domination or even to leave the country.

There seems, however, little possibility of any considerable immigration, owing to the fact that South Africa cannot easily absorb newcomers unprovided with a considerable capital and also owing to the general hostility both of the Nationalist and Labor parties to any active policy of immigration. The immense reservoir of unskilled labor, at cheap rates of pay, which the natives supply, makes it useless to import unskilled white laborers, without capital, expecting to find employment; and, moreover, the threat of widespread unemployment for white unskilled workers already in the Union is very serious. So far little has been done to meet this pressing internal problem of the “poor white” or “bywoner.”

The effect in South Africa of the juxtaposition of the white and black races has been that Europeans will not do what is regarded as kaffir’s work and reserve to themselves every employment requiring any degree of technical skill and resolutely refuse to perform what are regarded as the inferior kinds of manual labor. Unfortunately in a country circumstanced as South Africa is to-day the result of this selective policy of aristocratic exclusion has been that there has grown up the large class of almost unemployable whites who have no place in the economic system because they are not trained to take “white men’s jobs” and are unable to live on the wages that would be paid to kaffir labor. This class is continuously increasing and Dr. Edgar Brookes, a leading Transvaal educationalist, quoting from the Director of the Census, has pointed out that “only 50 percent of our boys and girls annually leaving school can now be placed in employment,” with the ultimate effect that to her other difficulties South Africa is adding year by year a problem that strikes at the root of the economic relations of white and black.

But the most far-reaching effect of the European colonization of South Africa has been the change it has wrought upon the native modes of life. Originally a pastoralist, owning cattle, sheep, goats, and, in some cases, horses, the kaffir has been taken in too many cases from his natural surroundings and thrown into the vortex of a new economic life foreign to all his experiences. To-day more than 12 percent of the natives are town dwellers, living in locations on the outskirts of the cities or in compounds in the mining areas, frequently amidst squalid surroundings and under hygienic conditions unworthy of a great and progressive community. The housing of the native workers in South Africa is a problem that affects the well-being of the black-and-white structure of South African society and is a serious cause of much of the native unrest.

The growth of the mining industry in the Transvaal and elsewhere has been detrimental to the true welfare of the natives in many ways. Moreover, those natives who have not been caught in the industrial machine, or who have returned to their tribal areas, only too frequently with the vices and few of the virtues of white civilization, find that the lands placed at their disposal are in many cases entirely inadequate for their needs, while, speaking generally, they have not been trained to make the best use either of the poorer lands at their disposal or of some of the undoubtedly fertile territories that still remain to them. There is something pathetic in the inexorable way in which the natives have been forced back into the remoter and less fertile parts of the country, although in contradistinction to many native races in like circumstances the kaffirs have not gone to the wall in the fight between the energy and business acumen of the European and the simplicity and lack of forethought of the native. They are, instead, intensely alive and are loudly clamoring for land in a country where the average per head on the native reserves available for their occupation is in some cases as low as 4.8 acres (Transvaal and Orange Free State) and nowhere more than 12.8 acres (Cape) as compared with the enormous farms held by Europeans. It is estimated that in South Africa only 13 percent of the land is set aside for 4,500,000 natives while 87 percent is reserved for 1,500,000 whites. The question of native reserves, coupled with the policy of racial and industrial segregation, is the immediate problem that faces the Union Government to-day.

The policy of General Hertzog, the Premier, outlined at Smithfield, Orange Free State, on November 13th, is one of segregation for the natives; but the whole question is so complicated by numerous factors that it is difficult to conceive how such a policy can be put into practice, even approximately. In no case is it possible to return the natives to the lands from which they originally came, to withdraw from the economic life of the community the vast numbers that have broken away from their tribal allegiance, to take from the white community the lands it already possesses, or to deprive the black man of his present means of education or to prevent its ultimate extension and improvement. By segregation General Hertzog probably means the extension, if that be possible, of the areas allotted to natives, in accordance with definite promises made in 1913, and the creation of some political means whereby the black man may be enabled to express his opinion and to press his views upon the white community. The political aspect of General Hertzog’s plan for the establishment of a Native Council to meet annually is already attracting great attention in the Union, where that part of the native population that has received some measure of education is clamoring for an effective constitutional means of expressing its desires.

His policy also involves what may be termed industrial segregation, or rather industrial reservation, a policy that strikes directly at the economic aspirations of the natives and is intended to prevent them from acquiring positions of trust, as skilled mechanics and workmen, to the detriment of the white workers. This policy is not new in South African politics for a color bar has long existed in the mines of the Witwatersrand by virtue of departmental regulations whereby special occupations, skilled and half skilled, were reserved for Europeans and half-castes. The regulation which provided that “the operation of, or attendance on, machinery shall be in charge of a competent shiftsman, and in the Transvaal and Orange Free State such shiftsman shall be a white man,” was unanimously declared to be ultra vires by the Transvaal Supreme Court in 1924, in a judgment which created great satisfaction among the black workers and produced a corresponding opposition among the white. This year, however, a Color Bar Bill was introduced, as the beginning of the government’s native segregation policy, which extended the industrial disability to the Cape Province and ran counter to Cecil Rhodes’s well-known policy of “equal rights to all civilized men south of the Zambesi.” This bill was thrown out by the Senate upon its first presentation, after the natives had been refused a hearing before the Select Committee dealing with it; it was reintroduced and again rejected by the Senate on March 17, 1926, and now will be submitted to a joint session of the two Houses of Parliament, under the terms of the South Africa Act of 1909.

Only the extension and radical reform of the present inadequate and, generally, inappropriate educational system is likely to lead to a solution of the racial trouble. The kaffir in South Africa must be trained for agricultural work, not exclusively on the farms of the white community, but in his own settlements. Industrial training must go hand in hand with agricultural education, but in this case it must be made certain that the black man be placed in a position where he can employ his training amongst his own people. Otherwise the economic pressure exerted by thousands of trained workers, competent to perform many jobs now exclusively confined to Europeans, will prove overwhelming in a country where the black flood, unless offered adequate safety-gates, will inevitably sweep away the economic barriers of an aristocratic civilization. At the root of the whole native question in Africa is vocational training for the land and one cannot do better than echo the words of Dr. Thomas Jesse Jones that “it has been a surprise that so few Europeans or Africans have realized that the most fundamental demand vocationally is for training to develop the soil possibilities of the great African continent” — a demand equally applicable to the Union of South Africa and the great tropical territories in the north. Given this fundamental change and a gradual removal of the barriers that shut out the educated black man from employment for which he has fitted himself, the problem of South Africa may be settled eventually by mutual consent.